Looking to land an elite defensive lineman? Head to the deep South

UCLA coach Rick Neuheisel posed a fascinating question during a conversation last summer. Where, Neuheisel asked, can a coach go to find the best defensive linemen?

Neuheisel had spent the offseason trying to replace star lineman Brian Price, so he knew the challenge of finding a 300-pound space eater who could hang with an elite sprinter for the first 10 meters of a race. Neuheisel wondered aloud if there is an area of the country that produces more quick, agile 300-pound tackles and blazing fast 275-pound ends than anywhere else. Neuheisel had good reason to ask. To a man, coaches say an elite defensive lineman is the toughest prospect to find and the biggest help to a program. "They can equalize a lot of problems for you," Arizona coach Mike Stoops said.

There is a region that produces a higher percentage of elite defensive linemen, and anyone who has watched the past five BCS title games should have an idea where to point on the map. Think back to who made the biggest plays in those games -- all of which were won by a team from the SEC. Following the 2006 season, Florida ends Derrick Harvey and Jarvis Moss and tackle Ray McDonald blew past flabbergasted Ohio State offensive linemen. The next year, LSU tackle Glenn Dorsey similarly flummoxed the Buckeyes. A year later, Florida end Carlos Dunlap seemed to be everywhere against Oklahoma. The next year, 300-pound Alabama end MarcellDareus knocked Texas quarterback Colt McCoy from the BCS title game with a sack and then returned an intercepted shovel pass 29 yards -- with a stiffarm and a pirouette -- for a touchdown.

Earlier this month, Auburn's Nick Fairley added his name to that list. The 6-foot-5, 298-pounder obliterated Oregon quarterback Darron Thomas' zone reads and singlehandedly disrupted an offense that had buzzsawed most of the Pac-10. "I don't know how many guys like Nick are out there," Auburn coach Gene Chizik said the next morning. "We are blessed to have him. They don't come along very often."

What do those linemen have in common? Except for Moss (Texas) and Harvey (Maryland), all played their high school football in the region commonly known as the deep South. McDonald is from Belle Glade, Fla. Dorsey is from Gonzales, La. Dunlap is from North Charleston, S.C. Dareus is from Huffman, Ala. Fairley is from Mobile, Ala.

So that provides an anecdotal answer to Neuheisel's question, but what about an empirical one? Which area of the country produces the most elite defensive linemen?

Simply logging the hometowns of football recruits -- as I did two years ago for the State of Recruiting project -- wouldn't answer the question. Such a study wouldn't address quality. So instead of using college players, I decided to use NFL players. Unlike quarterback, the defensive line positions have few political underpinnings. It doesn't matter how much a guy gets paid. If he gets blocked too often, he gets cut. The NFL's Darwinian nature allows us to be reasonably confident that the defensive linemen on the rosters now are the best the world has to offer at the moment. So I logged the high school hometowns of all 309 defensive linemen who ended the 2010 season on a roster or on injured reserve to get a snapshot of which areas produce the most elite defensive linemen.

The results won't make Neuheisel feel any better.

Despite the fact that the region accounts for only 22.1 percent of the nation's population, 43 percent of the NFL's defensive linemen went to high school in the following 10 states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee.

Now let's look at another 10-state region that accounts for 22.5 percent of the nation's population. Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah and Washington produced just 13.6 percent of the NFL's defensive linemen. The region that is home to the Pac-10 -- soon to be the Pac-12 with the addition this year of Colorado and Utah -- suffers from a severe shortage of elite defensive linemen compared to the region populated by the schools of the SEC and the ACC.

(It should be noted that despite the quantity, the quality out West is quite high. The aforementioned Price came from LA's Crenshaw High and dominated in college, while Nebraska Cornhusker-turned-Detroit Lion Ndamukong Suh -- perhaps the most dominant college defensive tackle of the past 10 years -- is from Portland, Ore.)

Things aren't much better in Big Ten country. While metro Detroit seems to be a productive pocket for defensive linemen, a nine-state region (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin) that is home to 22.5 percent of the nation's citizens produced just 13.6 percent of the NFL's defensive linemen.

Just as it did in the State of Recruiting project, Florida led the nation in players produced. The state of 18.5 million produced 35 linemen. Texas produced a whopping 26 NFL defensive linemen, but Texas is a whopping state of 24.8 million citizens. For better economy, go to Louisiana, a state of 4.5 million that produced 17 players, including Dorsey and end Tyson Jackson (Edgard, La.), who were teammates at LSU and now play together in Kansas City.

The only region that seems to come close to the South in terms of production is the Eastern Seaboard. Maryland, the District of Columbia and New Jersey all produced more than their share of players relative to their populations.

Oregon coach Chip Kelly believes teams in a defensive lineman-rich region have an inherent recruiting advantage. While Kelly can pluck skill players from Florida or Texas that fit his offense -- but maybe not the offenses at Florida, Florida State or Texas -- he can't easily grab a defensive lineman because all those schools want elite linemen just as badly. A 300-pounder who can run fits in every scheme. "Most of the recruiting we do is geographic -- on the West Coast," Kelly said in a July interview. "We've expanded, but I think you can expand to get a skill kid. I'm not sure you can expand to get that type of d-line prospect. That's always the toughest one."

For West Coast programs that can afford the steep airfare, the best bet is to cast their nets even further west into the Pacific. Hawaii produced five NFL linemen, and tiny American Samoa (population: 67,190) produced six. Those who can't afford the flights to paradise may want to check closer to home in Salt Lake City, a metro area that produced five NFL linemen -- including former Oregon great Haloti Ngata. Like Ngata, three of the other future NFL linemen who grew up in Utah are of Polynesian descent. Salt Lake City has a high Polynesian population because the Mormon church does extensive missionary work in the Pacific islands, and many families have relocated from the islands to Salt Lake City, where the church is headquartered.

Anthropology may help explain why so many good linemen developed in certain areas. Many of the linemen from west of the Rockies are of Polynesian descent. Polynesian cultures tend to produce large men capable of generating massive amounts of force. And with good reason. "Big, fast males sound like what ought to come out of centuries or millennia of social systems where there is direct male-to-male violence, but not where there are standoff weapons used in war like bows and arrows," University of Utah anthropology professor Henry Harpending wrote in an e-mail. "There was certainly this kind of violence on Polynesian islands, which were demographic pressure cookers."

Harpending is one of the authors of The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution, which argues that, contrary to popular belief, the advent of advanced societies didn't stop human evolution but actually kicked it into a higher gear. In a phone interview, Harpending called the development of the Polynesian islands "a unique experiment in human history."

"They were fighting for land," Harpending said. "There just wasn't enough arable land in most places. The records and the archaeology both show that there was just a lot of warfare, violence, turnover of chiefs."

Harpending wrote that it might be more difficult to explain the anthropological reasons for the explosion of players in the South without knowing more specifics about their ancestries. Most would be classified by the U.S. Census Bureau as black, and Harpending said most black Americans are descended from ancestors who lived in the tropical regions of central Africa. He wrote that throughout history, most violence in those areas tended to be "hand-to-hand," which would have produced large, fast, muscular males through natural selection. Like the Polynesians, ancient people in central Africa never favored the bow-and-arrow as a hunting or warfare tool. Harpending said archaeological evidence from central Africa shows the ancient residents preferred spears and bludgeoning instruments. In other words, the biggest and strongest would have survived the fighting to reproduce. "Bows and arrows kept the distance between people," Harpending said. "It decreased the premium on being big and strong."

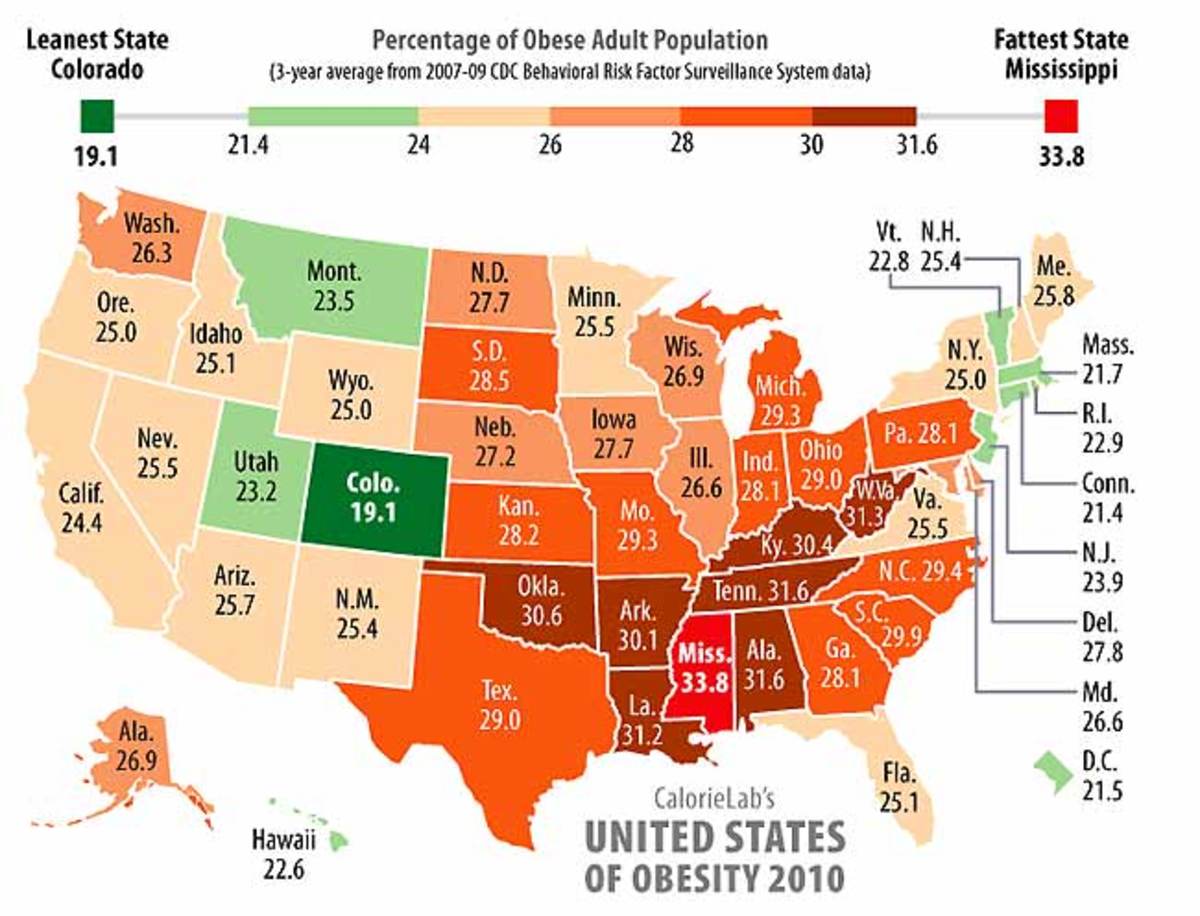

Another factor may help explain the greater numbers from the South. When they're placed side-by-side, it's difficult to tell the difference between the clustering in a map of the NFL defensive linemen's hometowns and a map showing the percentage of obese people in each state.

While many of the linemen have low body-fat percentages now, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of players ballooning once they leave behind intense daily football workouts. So it might make sense that Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee -- which produced 30.7 percent of the NFL's defensive linemen despite having just 14.7 percent of the nation's population -- would be among the nation's fattest states. According to data obtained from the Centers for Disease Control by calorielab.com, Georgia ranks the lowest of the group with 28.1 percent of its adults classified as obese. Mississippi, meanwhile, is the nation's fattest state with 33.8 percent of its adults classified as obese. None of the Pac-12 states are higher than 26.3 percent, and Colorado is the nation's thinnest state at 19.1 percent.

So what's a coach from a less fertile area to do? First, he should develop a taste for barbecue. The best is found in the states that produce elite defensive linemen. Second, he should look hard at some of the linemen the SEC and ACC schools don't sign. There are diamonds in the rough. After living in England and Nigeria, current New York Giant Osi Umenyiora played at Auburn (Ala.) High. The hometown Tigers didn't sign him, though. Troy did. George Selvie was a lightly recruited offensive lineman from Pensacola, Fla., who became an All-America defensive end at South Florida.

Fort Myers, Fla., native Terrence Cody almost couldn't find a junior college willing to take him. After he starred at Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College, a host of SEC and ACC schools looked at his highlight video and passed. Alabama coach Nick Saban took a look as a favor to GCCC assistant Stevon Moore, whom Saban had coached while with the Cleveland Browns. In the massive -- at the time, he weighed almost 400 pounds -- Cody, Saban saw the perfect nose tackle to clog two gaps at once in Alabama's 3-4 defense if he could shave some weight off the freakishly-athletic-for-his-size Cody.

Of course, no coach can resist ready-made athletic freaks who already can change a game from end or tackle. The recruiting class of 2011 can begin signing with schools on Wednesday, and the jewel of the class is defensive end Jadeveon Clowney. Clowney is a 6-6, 250-pounder who runs like a cheetah chasing down a gazelle for dinner.

And from where does young Mr. Clowney hail?

Sorry, Coach Neuheisel. He's from Rock Hill, S.C.