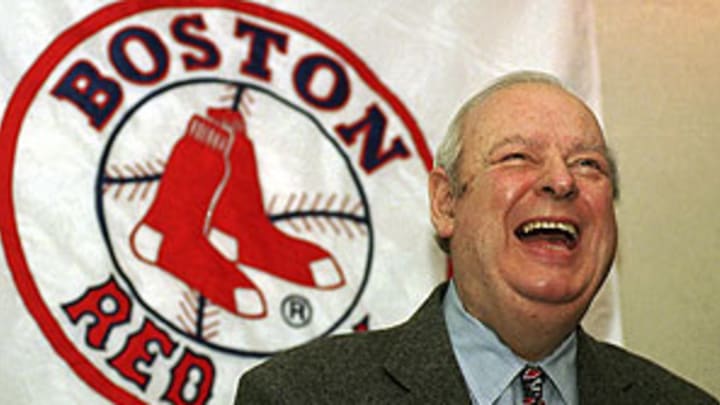

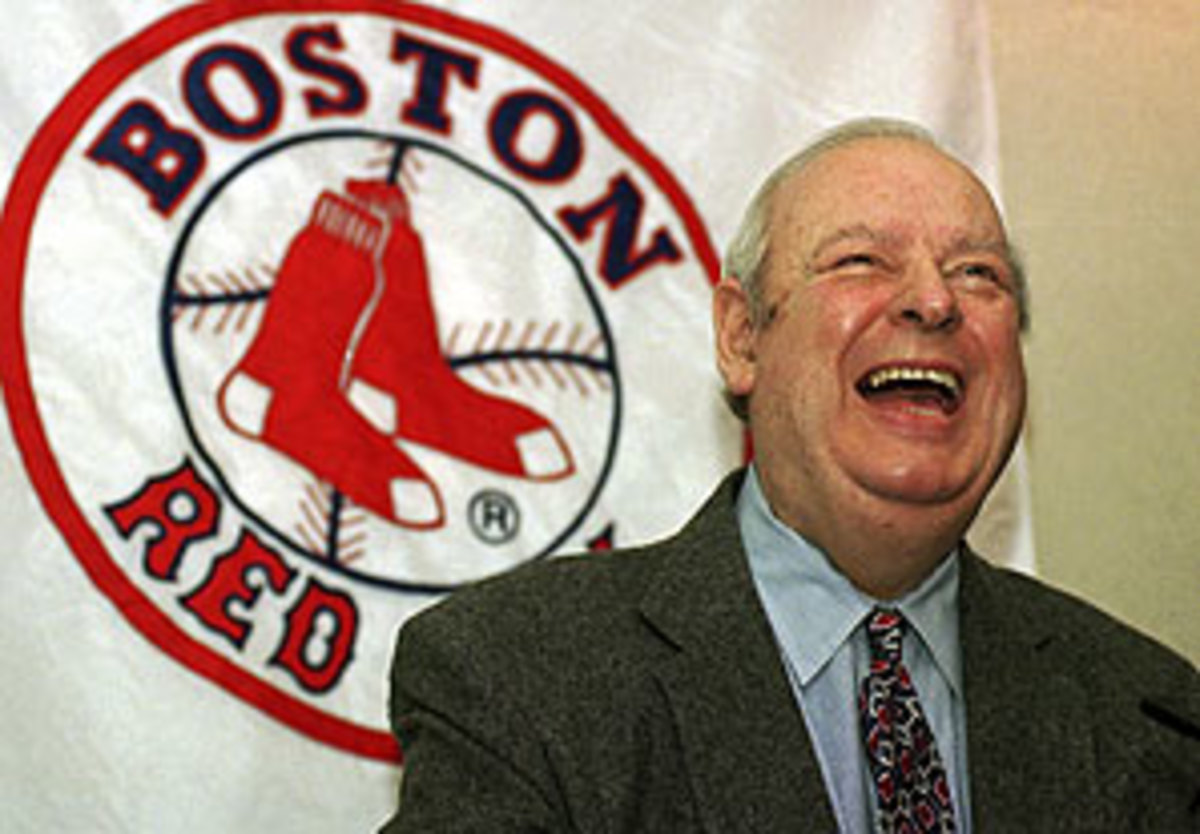

Fondly remembering former Red Sox architect Lou Gorman

One of my favorite moments in baseball came in the spring of 1987 when young Red Sox ace Roger Clemens walked out of spring training camp in Winter Haven. Clemens was reigning Cy Young and American League MVP. It was a pretty big deal when he stormed off the premises after the Sox renewed his contract for low dough. Thirsty for official club reaction, reporters surrounded Sox general manager Lou Gorman.

Ever polite and accommodating, Gorman answered all of our questions. Then, in an effort to put things in perspective and dial down the hysteria, he said, "The sun will rise, the sun will set, and I'll have lunch.''

And so we all had lunch and life went on, and a month later Clemens was back and he won the Cy Young Award again in 1987.

Last week Gorman died on the first day of the Red Sox 2011 season. He was 82.

Lou was instrumental in building five baseball teams. He also worked for the Orioles, Royals, Mariners and Mets. He didn't win championships as a GM, but the World Series trophy often arrived soon after he left and there was a reason for that.

There was no Moneyball in Lou Gorman. He was decidedly old school. He did not rely on spreadsheets or computer printouts. I never heard him talk about WHIP, UZR or even OPS.

Born James Gorman, Lou grew up in Rhode Island and picked up his nickname as a flossy-fielding first baseman back in the days when folks still remembered watching Lou Gehrig. After a hitch in the Navy (Lou ultimately retired as a captain in the Naval Reserve) Gorman got into baseball in 1960 when he was 31. He went to the annual winter baseball meetings in Tampa and stalked the lobby for five days until he was hired by Howard Roth of the Lakeland Giants. In 1963 Gorman was hired in Baltimore by Lee MacPhail and Harry Dalton.

Lou never looked back after his start in Baltimore. In the Orioles' system he worked with Earl Weaver, Billy Hunter, Cal Ripken Jr., Jim Frey, Joe Altobelli, Darrell Johnson and George Bamberger. All would eventually manage in the major leagues. He won a World Series with the Orioles organization in 1966, then left for Kansas City, joining the expansion Royals in 1968.

Gorman was an innovator. At Kansas City he was a key player in the experimental "Baseball Academy.'' In 1976 he left Kansas City to join the expansion Seattle Mariners. At that time he was the only executive to have been at the helm of two startups.

In 1980 Lou left Seattle and took over the New York Mets. In '84 he left the Mets and came home to the Red Sox. The Sox were a dull franchise in those days and Lou became the face of the organization. Within three seasons he had his Red Sox in the seventh game of the World Series. Against the Mets club that he'd help build.

His finest hour turned into his worst moment. The Sox were poised to win the '86 World Series. They led the Series, 3-2, and led Game 6, 5-3, with two outs and nobody aboard in the bottom of the 10th. And then the Sox collapsed. You might remember it as the Bill Buckner game. It was a cruel blow for Gorman.

Lou was at the top of his game from 1986 to '90. The Sox finished in first place in 1986, '88 and '90. They were back on the map.

But then some unfortunate things happened. In the stretch run of 1990, the Sox needed bullpen help and Gorman sent minor league third baseman Jeff Bagwell to the Astros for a journeyman middle reliever named Larry Anderson. It would never be forgotten. Lou defended the Bagwell deal until his dying days.

Things went downhill from there. In the early '90s, Gorman hired Butch Hobson to manage the Sox. It was a disaster. The Sox slumped and Gorman was harpooned by the Boston media.

"If I were in Cleveland, they'd build a statue of me downtown,'' he said. "In Boston, they criticize me.''

In 1994 Gorman was moved upstairs and Dan Duquette was brought on board as general manager. Nine years later new Sox ownership took a chance on a 29-year-old kid named Theo Epstein.

Lou was still a part of the Sox organization when they finally ended the Curse of the Bambino and won a World Series in 2004. The '04 team was built by Duquette and Epstein -- with help from Gorman, who drafted Trot Nixon and several of the players Duquette and Epstein used as trade fodder.

A baseball lifer, Lou stayed around Fenway in his final years. He was always available to help a college kid or tell stories about the grand old days of baseball. He was one of the finest men I have ever known.

If you have a son, you want that boy to grow up to be like Lou Gorman.