What Keith Richards -- yes, Keith Richards -- taught me about sports

I once played golf with Jesse Ventura, who brandished a telescopic ball retriever throughout our round and probed the many ponds for other people's Titleists. "I'm lookin' for Pro V1s," explained The Body, who was the sitting governor of Minnesota at the time. "Those puppies are five dollars a ball."

His frugality was born of economic necessity. In his wrestling days, Ventura said, when incapacitated by injury, he made ends meet as a stage security guard for concerts at the Met Center, where the Minnesota North Stars played hockey. When the Rolling Stones played the Met in 1978 and '81, Ventura worked their shows. Two decades later, the Stones again played the Twin Cities, and this time Ventura met them -- as governor -- and told Keith Richards that he used to serve as muscle on their stage.

"Let me get this straight," said Keef, who I like to imagine was in a silk kimono, and clutching a lowball glass of Jack Daniels. "You body-guarded us in '81, and now you're the Guv'nor?"

Keef thought about this for a moment, then said with a twinkle: "F-----' great country, mate."

Because of this story, and where I heard it, and from whom, I have associated Richards ever since not with snorting his own father's ashes, or falling out of a tree in Fiji, or writing "Gimme Shelter." No, when I think of Keef I think of golf and hockey and professional wrestling.

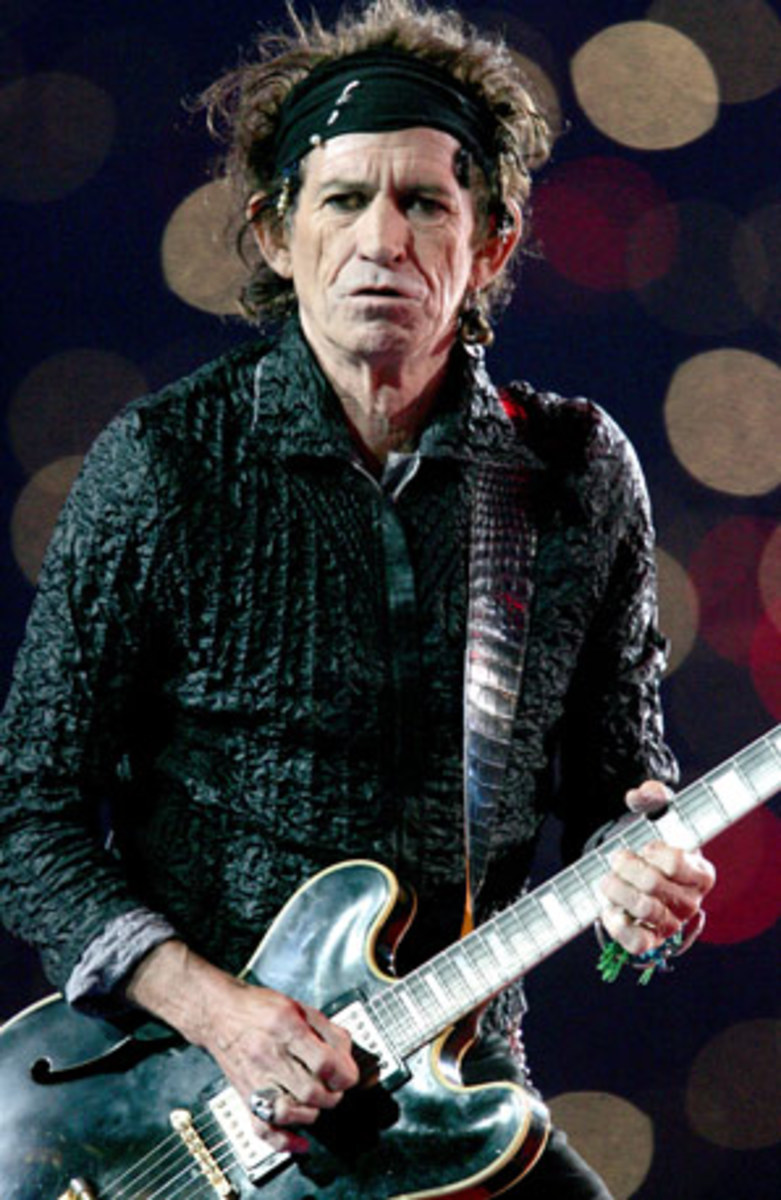

True, the piratical guitarist was no athlete -- his mother Doris said young Keith ran away from the soccer ball whenever it was passed to him -- nor much of a fan. But while tearing through Life, his 564-page autobiography, I was struck by how much Richards resembled a professional athlete. And how much he had to say, without knowing it, about athletic genius.

It's not just the performance-enhancing drugs, though the peak years of Richards' career, like those of so many superstar athletes, were a dizzying pharmacopoeia of ingestions and injections and legal injunctions.

No, there was also the freakish sports injury that he succeeded in spite of (at first) and because of (later). As a kid playing street soccer in the London suburb of Dartford, Keith moved a flagstone paver out of the way and dropped it on his right index finger, smashing it. "It really flattened out the finger for pick work," Keith writes. "It could have something to do with the sound. I've got this extra grip."

I thought of Larry Bird's right index finger. It was broken by a softball line drive off the bat of his brother Mike and forever bent at a 45-degree angle, which should have -- but somehow didn't -- adversely affect his shooting. On the contrary, Bird and Richards became virtuosos, their mangled fingers "having something to do with the sound."

There are early scenes in Life that appear in almost every athlete's autobiography, in which fear and failure on the playground prove foundational. In Keith's case, he was a year younger than his classmates, often bullied and called "Monkey" for his big ears. I thought of Michael Phelps, also bullied as a child for his ears.

Keith hated rugby and was called a pansy. "The playground's the big judge," he writes. "That's where all the decisions are really made. It's called play, but it's nearer to a battlefield, and it can be brutal, the pressure." Keith went to art school and started the Rolling Stones. Michael Phelps went to the pool and won 16 Olympic medals.

Phelps found satisfaction. Keith wrote "Satisfaction."

When he was at Inter Milan, I asked another genius, Ronaldo, to describe being in the proverbial zone, a precinct few of us will ever visit. "There are no words," he said. But Keef -- as befits a man who wrote "Jumpin' Jack Flash" about his gardener, Jack -- is seldom short of a felicitous phrase.

"Levitation is probably the closest analogy to what I feel -- whether it's 'Jumpin' Jack' or 'Satisfaction' or 'All Down the Line' -- when I realize I've hit the right tempo and the band's behind me. It's like taking off in a Learjet. I have no sense that my feet are touching the ground. I'm elevated to this other space."

That's why he doesn't retire. He's not doing it for you, Keef says: He's doing it for Keef.

At 67, his face cross-hatched with crevasses, Richards is often asked about retirement. But like countless athletes -- Brett Favre comes immediately to mind, Cal Ripken is another -- he refuses to retire on someone else's timetable, simply to preserve your memories.

This is what so many of us fail to grasp about athletes. While we clamor for them to step aside -- so as not to sully our memories -- we fundamentally misunderstand them. They're not doing it for us, nor should they be.

In the end, there's some freakish spark, defying explanation, common to Keef and others touched by greatness. Mario Lemieux this winter attributed the brilliance of Sidney Crosby to one fact: "He thinks about hockey 24 hours a day, even in his sleep." Lemieux was in a position to know of Crosby's nocturnal devotion, having had him as a housemate for five years.

Keef did Crosby one better. He seldom slept at all. "For many years I slept, on average, twice a week," he claims. "This means I have been conscious for at least three lifetimes." Ah, but when Keith did sleep, he was dreaming about his art. He not only wrote "Satisfaction" in his sleep, but also played it for the first time in his sleep that same night.

He woke with no memory of the song, but pressed play on the Phillips tape recorder next to the bed anyway -- just in case. What he heard was the now-indelible guitar riff, followed by 40 minutes of snoring.

If that isn't genius, we have yet to discover it.