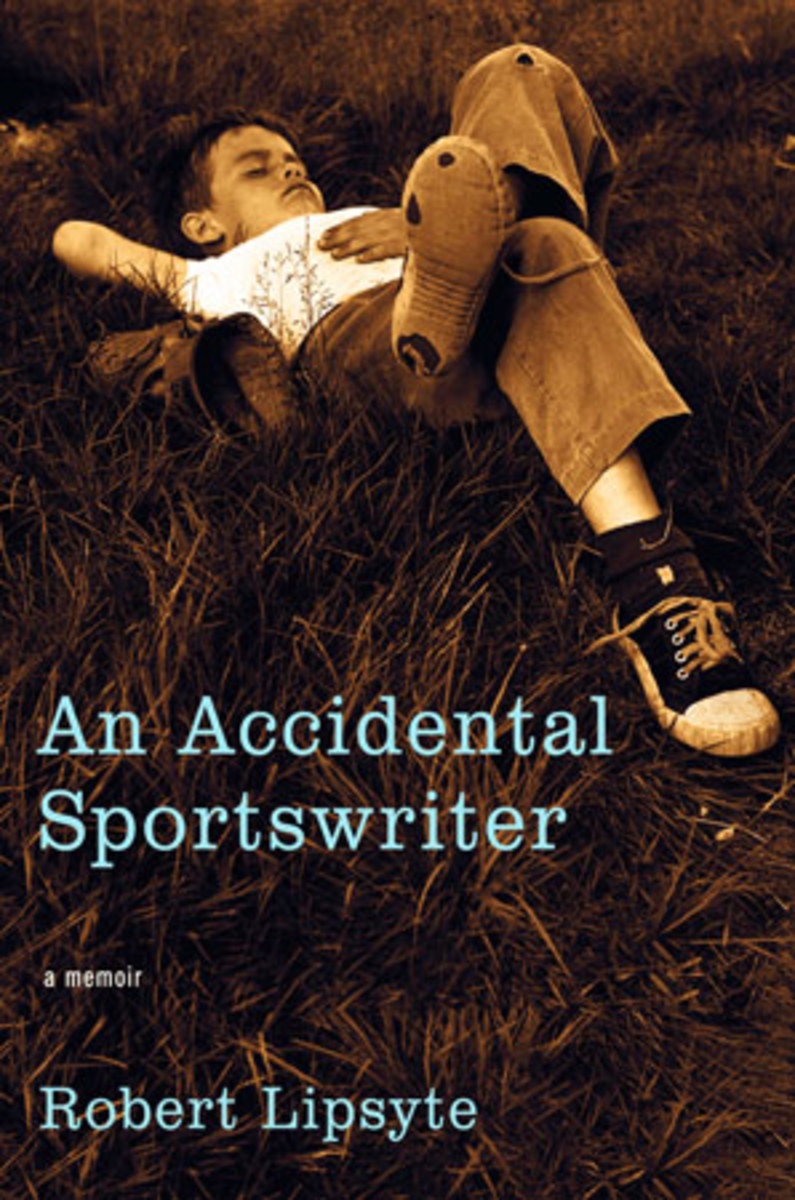

A poignant portrait revealed in An Accidental Sportswriter

Robert Lipsyte never wanted to be a sportswriter, never mind one for The New York Times. "A fat boy growing up," he writes in his revealing new memoir An Accidental Sportswriter, "I didn't even start playing sports seriously until I was in my teens ... and not only had I never read the Times sports pages, I had barely read the Times at all."

But in 1957 he took a summer job as a copyboy in the Times sports department. That fall Lipsyte was supposed to start grad school in California. He ended up never leaving New York. Instead, he became enamored with sports feature writer Gay Talese, who took Lipsyte under his wing, teaching him that a good journalist always asks unusual questions, especially "Why is that?"

A couple years later, when Lipsyte told Talese he was quitting the Times, Talese asked: "Why is that?"

It came down to frustration and impatience. By that point, Lipsyte was taking graduate courses at Columbia, writing features stories for the J School newspaper, and feeling underappreciated and overworked in his night job at the Times.

Talese seemed to get it. Rather than trying to talk him into staying, Talese offered to give him $5,000 in exchange for 10 percent of Lipsyte's future earnings as a freelance writer over the next 10 years.

"I lost my breath," writes Lipsyte, who was making $35 a week. "He was offering me three times my annual salary. He believed in me."

No one had ever shown that kind of confidence in Lipsyte. It convinced him to stick around. He got elevated to reporter and in 1964 he got his big opportunity.

"Ali was my first Big Story," Lipsyte writes. "He put my name on Page 1."

But even this was an accident. In 1964, Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay) was scheduled to fight Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title. Liston was a 7-1 favorite. The Times was so convinced that the fight would be one-sided that it didn't bother sending its regular boxing writer to cover it. Instead, the paper dispatched Lipsyte, who went down to Miami a few days early in hopes of catching up with Ali.

An Accidental Sportswriter becomes instantly entertaining when Lipsyte recounts his visit to the old Fifth Street Gym in South Beach to watch Ali train. It was February 18, 1964. Lipsyte was 26. Ali was 22. "The first time I ever saw him, I was standing with the Beatles," writes Lipsyte. "Four little guys around my age in matching white terry-cloth cabana jackets were being herded up. Someone said it was that hot new British rock group on their first American tour. I was annoyed ... . These noisy mop tops were trying to cash in on the sweet science."

The Beatles were there for a photo-op with Ali, whom Lipsyte was waiting to interview. When the young reporter introduced himself to the Beatles, they mocked him. "John shook my hand gravely, saying he was Ringo, and introduced me to Paul, who said he was John." Then they ignored Lipsyte. When he asked their prediction on the fight, all four Beatles said Liston would destroy the challenger.

Then the locker room door flew open. "Hello there, Beatles!" Ali roared.

Lipsyte observed as the Beatles playfully lined up and then fell like dominoes when Clay hit them with a soft punch. It resulted in a timeless, classic photograph. Lipsyte had no idea he was watching history in the making.

But he figured it out when he witnessed Clay dominate Liston, taunting the heavily favored champ and then mocking the press when Liston refused to come out of his corner for the seventh round. "Eat your words!" Clay shouted to the ringside media. Clay had arrived.

So had Lipsyte's moment. He banged out his first front-page, above-the-fold story. This was his lede: "Incredibly, the loudmouthed, bragging, insulting youngster had been telling the truth all along. Cassius Clay won the world heavyweight title tonight when a bleeding Sonny Liston, his left shoulder injured, was unable to answer the bell for the seventh round."

And just like that, a sports journalism career was launched. The Times anointed Lipsyte its new boxing writer. "My Ali coverage gave me confidence that hard, dogged work would allow me to compete successfully with the top sportswriters," Lipsyte writes.

He did more than compete. Within three years of covering the Ali-Liston fight, Lipsyte became a Times columnist, where he quickly established himself as an edgy voice of dissent in the world of sports. "The first two Super Bowls I covered (II and III) were bang-up football games," he writes. "What fun I had, drinking with coach Vince Lombardi, hanging out with Joe Namath, meeting sportswriters from all over the country! But after that, the glorification of real and symbolic violence in a time of war, the corporate involvement, and the defining of manhood through the game seemed at least as compelling as the play-by-play."

An Accidental Sportswriter is irresistibly readable. I flew through the 244-page book in one night. It made me laugh, cry and cheer, while taking me through some of the biggest moments in sports. I couldn't put it down. True to form, Lipsyte is brutally honest and controversial. But he's also poignant, both about himself and the sports icons he covered. His revelations about his encounters with Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio, Billy Jean King, Ali, Greg Louganis and Lance Armstrong kept me wanting more. Yet the are tempered with humor.

Some of the funniest passages come from long, close relationship with Howard Cosell, whom he refers to as Uncle Howard. After Lipsyte published his book SportsWorld, he was walking down the street with Cosell when they passed a crowded bookstore. Cosell encouraged Lipsyte to go inside, announce himself and offer to sign books.

Lipsyte isn't the type. Cosell was. He grabbed Lipsyte's arm, dragged him inside and bellowed: "I am standing here with Bob-bee Lip-syte, the greatest sportswriter of ... our ... time. If you buy his new book, SportsWorld, I will autograph it." Lipsyte sold a pile.

But I never read Lipsyte as a great sportswriter. Sportswriters cover what goes on between the lines. Lipsyte didn't care much about that. He lived outside the lines, where the questions and stories that matter more reside. That's where he had the homefield advantage over other scribes. His irreverent questions and bold stories forced us all to reexamine the way we look at sports and life. His new book does the same thing, only on a much grander scale.