Disparity in stars may be the difference in Heat winning title

In the annals of sports marketing, there have been some sensational lousy ideas. A glowing hockey puck. A Disco Demolition Night. The XFL. Reebok's Dan and Dave campaign.

But the Miami Heat's "Welcome Party" might top the list. With Sports Nation still recovering from the sheer awfulness of "The Decision," the Heat sales force held what amounted to a victory party before there were any victories. LeBron James, Chris Bosh and Dwyane Wade emerged from behind a curtain at AmericanAirlines Arena and came out to strobe lights, fog, and a pulsing beat as thousands of adoring fans went nuts. Though the Heat had yet to play a game, the night's slogan was: "Yes. We. Did."

This ill-conceived, comically over-the-top, self-glorifying event, had the dual effect of making the Heat the easiest basketball team to root against since Muncie Central in Hoosiers and heaping more expectations on the Big Three. Anything short of a championship was going to be a failure.

But for whatever they may have lacked in taste, at least the marketing department had the math right. For as often as we hear that "there's no I in team," it's not the case. Teamwork and unity and selflessness are virtues, no doubt. But especially in basketball, having stars -- having "I's" who will demand the ball and take the difficult shots, and put up stats that disrupt balance -- is vital. And by signing three stars, the Heat radically improved their chances of winning an NBA title.

If we were to compile a list of the top, say, five or six NBA players over the last 20 years, it would likely include ... whom? Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, Tim Duncan, Shaquille O'Neal, Hakeem Olajuwon and LeBron James. If there were no "I" in team, these stars wouldn't much matter. A team that formed a symphonic whole, with five players suppressing ego for a common goal, could surmount teams with the "I" players, stars willing and able to play selfishly when the situation calls for it. But that's rarely the case. Since 1991, every year at least one of those aforementioned players has appeared in the NBA Finals. Go back another decade and add Larry Bird, Magic Johnson and Doctor J., and now at least one of the top players have been featured in all but one NBA Finals series for the last 30 years. In other words, a remarkably small number of select players have led their teams to the vast majority of NBA titles. And lacking one of the best players in history has all but precluded a team from winning.

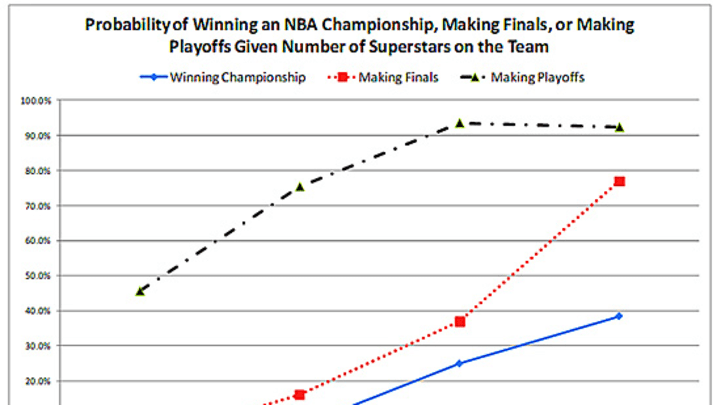

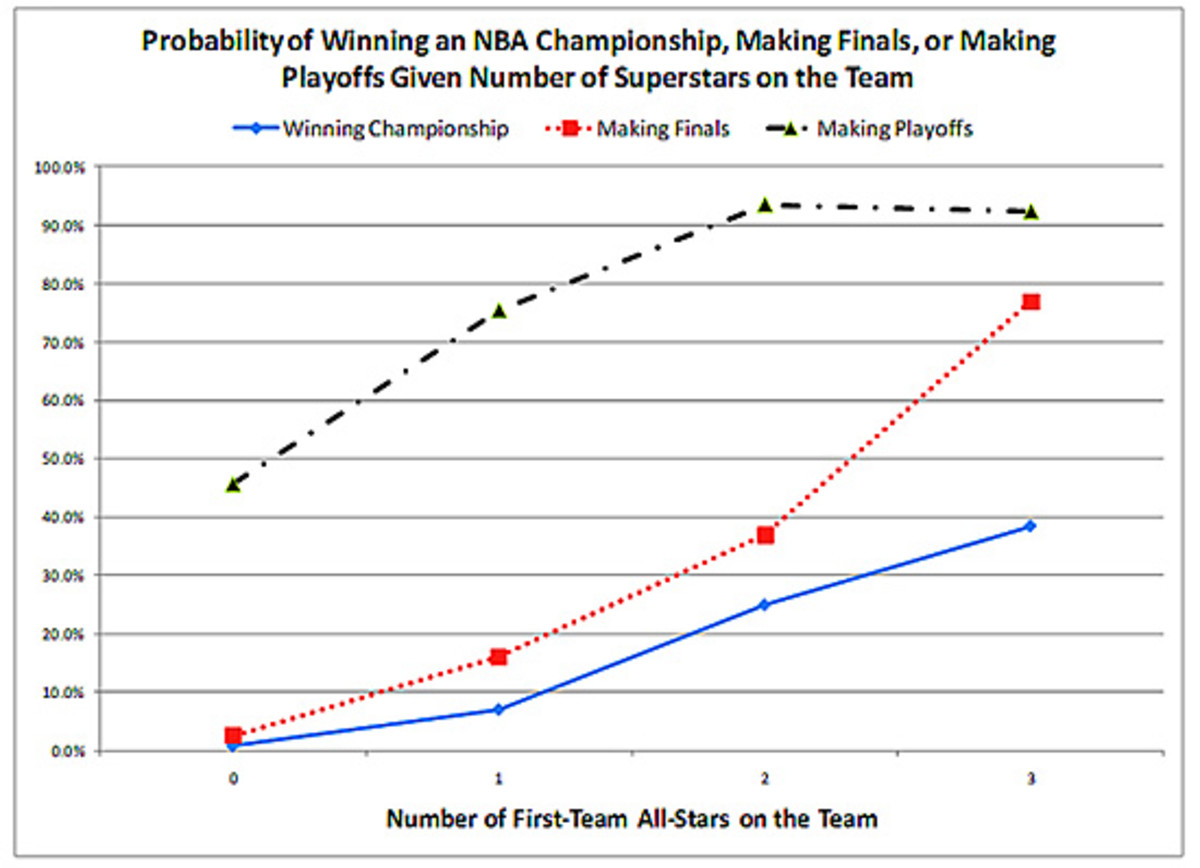

We wondered: how likely is it that an NBA team without a superstar wins a championship, makes it to the Finals, or even makes it to the playoffs? We can define "superstars" in various ways, such as first-team All-stars, top five MVP vote getters, or even those with the top five salaries. Pick your definition; it doesn't much matter. Here's what we found for the NBA:

An NBA team with no star on the roster has virtually no chance -- precisely it's 0.9 percent -- of making it to the NBA Finals, much less winning the championship. Put differently, more than 99 percent of NBA Finals involve a superstar player. The graph also shows, not surprisingly, that as a team gains superstars, its chances of winning a title improve dramatically. One first-team All-Star on the roster yields a 7.1 percent chance of winning a championship and 16 percent chance of making it to the finals. A team fortunate enough to boast two first-team All-Star players stands a 25 percent chance of winning a championship and 37 percent chance of making the Finals. On the rare occasions when a team was somehow able to attract three first-team All-Stars, they win a championship 39 percent of the time and make the Finals 77 percent of the time. Having an MVP-caliber player in James (or Wade) in addition to two other All-Stars made the Heat 98 percent likely to make the playoffs, 70 percent likely to make the Finals, and 36 percent likely to win it all.

What about the notion that a lineup of five solid players is better than a starting five of one superstar and four mediocre supporting roles? One way to test this idea is to look at the disparity among a team's starters in terms of talent. Controlling for the same level of ability, do basketball teams with more evenly distributed talent fare better than teams with more dispersed talent? Measuring talent is difficult, but one reasonable metric is salary. Controlling for the average salary and winning, we find that teams with bigger differences in salaries among their starting players fare better than teams whose salaries are more evenly spread among them? In other words, a championship team needs talent by UNEVENLY distributed.

But, here's also where it gets interesting. Even after controlling for the team's winning percentage during the regular season, teams with superstars do measurably better in the playoffs. That is, a top-five MVP candidate improves his team's chances of winning a championship by 12 percent and of getting to the Finals by 23 percent, even after accounting for the regular season success of the team. This implies that superstars are particularly valuable during the playoffs.

Which is pretty much what's happened in the postseason. LeBron James and Dwyane Wade have, overall, been typically excellent. And -- despite playing against better opposition -- Chris Bosh has been appreciably better than he was during the regular season.

Assuming Miami gets to the Finals against Dallas, it's clear which team the numbers support. Miami has the Big Three. Dallas has Dirk Nowitzki, perhaps the MVP of the 2011 NBA playoffs. But after Dirk, there's much less variance on the Dallas roster.

Horrible as the "Welcome Party" last summer was, if form holds, barely a year later, it will look less like a provocation to hate and more like a dress rehearsal for a Championship Celebration. And, the Heat will add one more data point, rejecting the "there's no I in team" cliche.