After years of hardship, Austin finds open wheel opportunity

With those implements packed in a Pontiac Bonneville named 'Bonnie', Chase Austin has traversed the South and the Midwest, searching for work in what has become an increasingly familiar slog the past six years. And a childhood reality turned dream might finally be coming true again.

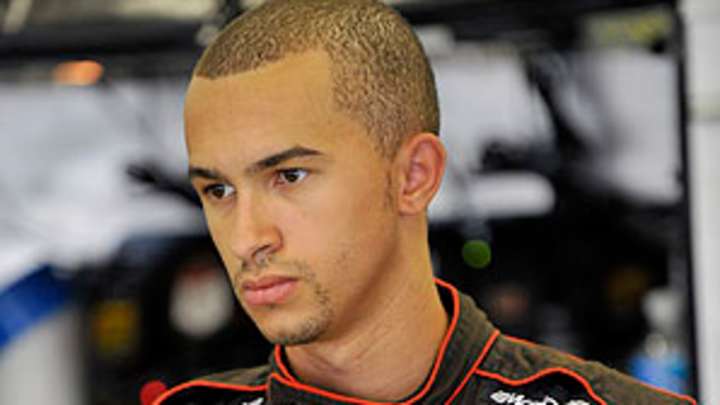

At 21, all too savvy about the business side of the sport that, fairly or not, was to make him the next breakthrough African-American driver in NASCAR and a bridge to the mainstream, Austin is returning to the Midwest for an unexpected homecoming and opportunity in the Indy Lights series, the feeder system for the IndyCar Series.

He's enthused. He's invigorated. But he's realistic.

"It's a job," said Austin, who makes his second career start on Saturday at Iowa Speedway. "I was in NASCAR and that's so hard to find a ride unless you bring money or have a sponsor. This was just an open deal and I wasn't doing anything else. You can't turn your nose at work."

Signed to a developmental contract with Hendrick Motorsports at 15 after being scouted racing -- very well -- against men twice his age, Austin was a go-kart and dirt-track prodigy. He seemed in prime position to build a career for himself and provide the ancillary benefit of increasing the profile of minorities in NASCAR when the sport and its teams were beginning to emphasize diversity initiatives.

But Hendrick Motorsports liquidated its entire developmental system -- including Blake Feese, Kyle Krisiloff and Boston Reid -- in 2005, and Austin did short, fruitless stints with Star Motorsports and Rusty Wallace's Nationwide Series team before recessing completely from NASCAR's higher ranks.

Austin believes the death of Ricky Hendrick, team-owner Rick's son, in a 2004 team plane crash prompted Hendrick, in part, to scuttle its developmental program. The team honored the entirety of its financial obligation to the Austins, said his mother, Marianne, but a third was surrendered in taxes.

"It's been really up and down," Austin said. "With the plane crash with Hendrick, it really did that in. Ricky Hendrick headed up the developmental program. It wasn't Rick's idea, and Rick really wanted [Ricky] to take over the company and that was his way of starting him toward it. That was the same year Jeff Gordon didn't make the Chase, and I was the low man on the totem pole, so it was a business decision. It was nothing personal. Then there were financial problems with teams. [The 2007 year] hit and the economy really fell out and it's still hard to find funding. That's been the biggest deal all the way on."

The 2007 opportunity with Rusty Wallace -- in which Austin raced in the K&N Pro Series and became the first African-American to race in a Nationwide oval event -- was doomed by a sponsor that was a home-builder and the fact Wallace wanted to advance the career of his son, Steve, who now races in the Nationwide series.

"It was [money] and his son wanted to race," Austin said. "He's looking out for his son's best interests and I couldn't blame him. If I were a dad I'd do the same thing. I didn't take it personally. It sucked on my end because I didn't get a ride anymore, but at the same time you've got to view it from their point of view. I couldn't bring any money to the table."

The Austins had split their family between their home in Eudora, Kan., and the Charlotte area after the Hendrick disappointment, with his mother at home working for her health insurance business and caring for his sister, Cara, Austin and his father, Steve, an uncle, Robert, and sister, Jessica, in North Carolina.

The family was saddled with a 7,500-square-foot shop, a USAR Pro Cup car and scores of parts when the Star Motorsports deal fell apart because the team, part-owned by the Wayans family of entertainers, failed to meet financial obligations. Rich in equipment but poor in crucial sponsor money after losing the valuable Hendrick clout, the Austins used the space to field a few part-time grassroots racing schedules around the south before finally parceling off all the parts and the shop a year ago. Austin competed in just two NASCAR events in 2010.

His next chance came in early May, when Chris Miles, who attempts to facilitate opportunities for African-Americans in racing, aligned Indy Lights owner Willy T. Ribbs and sponsor American Honda for a one-off during the weekend of the Indianapolis 500. Austin, with a day of testing at Chicagoland in his only open wheel experience since age 14 in sprint cars, finished ninth.

"He's almost an old soul for 21. He might as well be 41 with his experience," Ribbs said. "That is great. That is really good. From the technical side that is good. When I was listening to him give feedback to his engineers and listening how precise he was with his comments, I thought he would be fine."

Ribbs, the first African-American to start the Indianapolis 500 in 1991, is a vociferous critic of NASCAR -- where he ran three times in 1986 -- calling the series' diversity efforts "a sham and a smoke screen to get the media off their back." He said IndyCar is "where Austin belongs, where all African-American drivers belong."

"[NASCAR] had a chance with Chase," he said, "What did they do?"

IndyCar and its sponsor base will have their chance if Austin performs. In finishing ninth in his Indy Lights debut, he became the first African-American to compete in the series and just the fifth to race at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. But neither novelty nor uniqueness has proved a sustainable source of sponsor-recruitment, in IndyCar or elsewhere.

"The long-term goal is with him in IndyCar," Ribbs said. "What happens in Indy Lights will determine how important this is to corporate America and underwriters. If they think it is important you will see him and see me.

"I'd love to see him with Ganassi or Roger Penske or Sam Schmidt. I am in no position to really drive his career like I'd like. And I'm not going to be selfish and try to hold onto him."