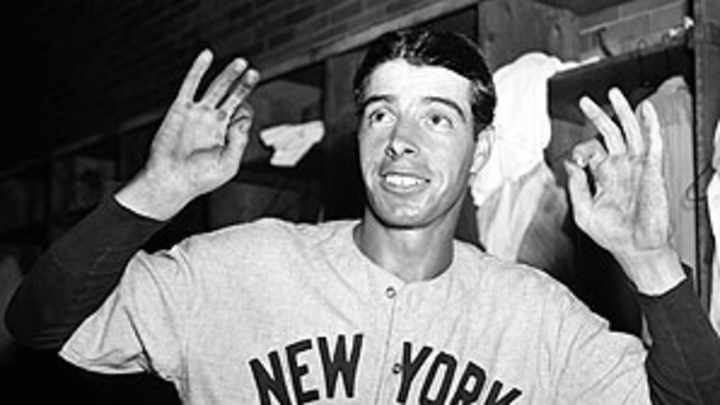

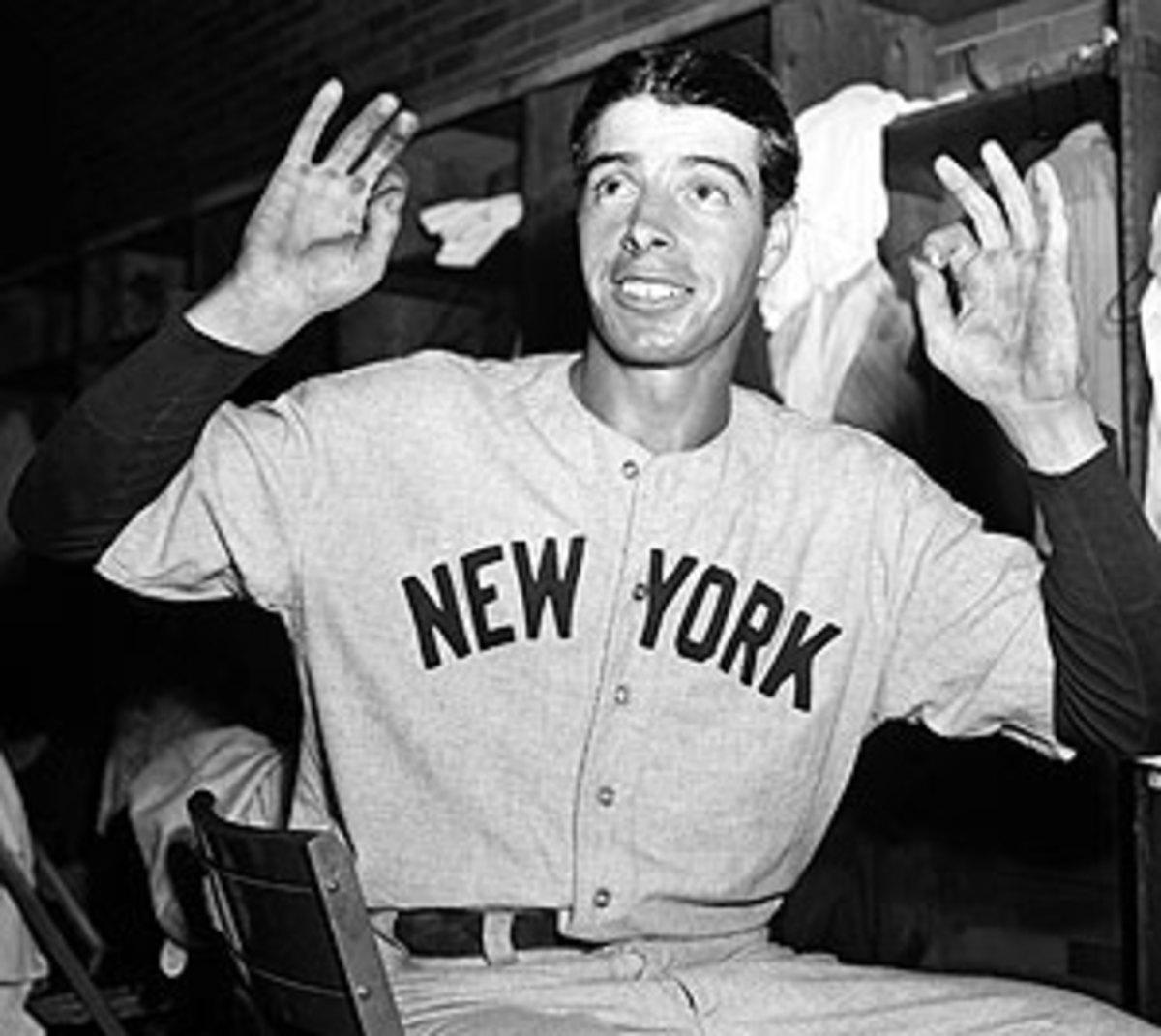

End of DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak changed lives forever

It was 70 years ago, on a mild and misty night in Cleveland, before the largest crowd of the 1941 baseball season -- 67,463 in Municipal Stadium -- that Joe DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak came to an end. The game became, in today's parlance, an "instant classic." It would have been destined for countless airings on many sports channels had only there been footage to air.

Instead the night of July 17, 1941 survived only in memory (and in some part myth), re-lived and re-told not just by DiMaggio himself but also by his teammates and by the opposing Indians players and by the coaches and the batboys and by the people who attended the game and by the many thousands more who were not at the game, but who would swear, year after year, that they were.

The facts are simple: DiMaggio went 0-for-3 with a fourth-inning walk. Yet each of DiMaggio's at-bats that night was an event, the mass of fans cheering and hooting each time he strode to the plate. Many of the people felt unsure whether or not they wanted to see the Great DiMag, as he was called, succeed against their Indians. Cleveland's ace pitcher, Bob Feller, felt that way as he watched from the Indians dugout. When I spoke to him, some nine months before his death at age 92 last December, Feller said he remembered the game clear as if the floodlights were still upon it.

"I wanted us to stop him, of course," Feller said, "we were trying to get to first place. But I also thought, Boy it would be nice if he keeps it going another day. I wanted to get a crack at stopping the streak myself." Feller was to pitch for the Indians the following night.

The outs are famous now, two of them anyway: the plays by third baseman Ken Keltner, a gold glover had there been such a thing back then. Twice -- in the first inning and again in the seventh -- Keltner dived to his left, into foul ground, to glove hard ground balls down the line and take doubles away from DiMaggio. The plays at first base were bang-bang close and DiMaggio believed that the wet ground (it had rained heavily the night before) had slowed his stride, costing him.

Keltner played DiMaggio on the edge of the outfield grass. On either at-bat Joe could have dropped down a bunt and made it to first base at a trot. That was just not something he would do, not even with The Streak on the line. ("Is DiMaggio a good bunter?" Yanks manager Joe McCarthy was once asked. "We'll never know," he said.)

DiMaggio's last chance came in the eighth, bases loaded, and ended when he hit a ground ball that Cleveland shortstop Lou Boudreau fielded on a bad hop and tossed to second base to start a double play. The streak was over.

The Cleveland crowd roared as loudly as it had all night and from the Yankees dugout the players -- including future Hall of Famers Phil Rizzuto, Lefty Gomez and Bill Dickey -- watched to see what DiMaggio would do.

Even with the hitting streak surely finished, DiMaggio did only what he would have done at any other time. After crossing first base, he slowed from his sprint, turned left and continued running toward shallow center field. Still moving, he bent and plucked his glove off the grass. He did not kick the earth or shake his head or pound the saddle of his glove. He did not behave as if he were aware of the volume and the frenzy of the crowd. He did not look directly at anyone or anything. Not once on his way out to center field did DiMaggio turn back.

After the game, Keltner was not pleased, but rather annoyed that the Indians had lost the game. Over the years, though, the fielding plays he made that night would come to define Keltner for many fans who otherwise might never have known his name. Once, when he met DiMaggio years later after both men had retired, Joe signed a ball for Keltner, inscribing it "To the culprit."

The Cleveland pitchers who stopped DiMaggio, Al Smith in the first three at bats, Jim Bagby Jr. in the final one, were similarly defined. Their roles in ending the streak were in the first paragraph of each of their respective obituaries.

DiMaggio wrestled with two emotions the night the streak ended: relief and sadness. "I'm glad it's over," he told reporters that night. "I've been under a strain." Later, though, he said that when he lost the streak it was like losing his best friend.

That night DiMaggio waited for the crowd outside Municipal Stadium to thin, then he left the ballpark with Rizzuto. They walked together up the hill toward their hotel. Then DiMaggio broke off and went into a little bar and grill, alone, to begin the rest of his life.

Even then McCarthy and other baseball men were saying that this was a record that would never be broken. And even then DiMaggio understood what he had achieved during those gripping weeks in the strange hot summer before the War. DiMaggio knew he had done something that would live with him always. Something crowning and indelible: 56.