Rugby World Cup champion Springboks inspired a nation

SI.com asked several current and retired SI writers to offer reflections on the best team they ever covered as sports journalists. Here's Ian Thomsen on the 1995 Rugby World Cup Champions, South Africa:I knew little about the sport when my boss at the International Herald Tribune, John Vinocur, said he wanted me to cover the month-long Rugby World Cup in 1995. Of the 65,000 people who would attend the championship final in Johannesburg, roughly 64,999 would know more about the game than me. But the game was only part of the larger story: This tournament would restore South Africa to the world stage after decades of isolation created by apartheid. That's why I think of the champion Springboks as the best and most important team I've ever covered.

Throughout the event I would speak a few times with Francois Pienaar, the Springboks captain, who was exceedingly generous with me in spite of my American accent. (Imagine Derek Jeter speaking with a Chinese journalist who knew nothing about baseball.) At 6-3 and 240 pounds, Pienaar was five inches taller than Matt Damon, who would be nominated for an Oscar for his portrayal of Pienaar in the 2009 film Invictus. Damon's understated performance was just right: Pienaar's muted dignity was crucial to the team's success, because a more boisterous leader would have inflamed the social and political tensions and distracted the Springboks from their mission on the field.SI VAULT:Bok to the Future (07.03.95), by E.M. Swift

I was able to see South African President Nelson Mandela several times during the tournament, and I was surprised by his accessibility. Near the finish line of a marathon, I found myself standing next to him, though his security guard would not permit me to introduce myself. The love for him among the non-white majority was overwhelming, and equal to the majority's hatred for rugby, which was the sport of the white minority that had enforced decades of apartheid.

During the tournament I visited the impoverished townships of Soweto, where a rugby field lay vacant, and Paarl, which was the home of Chester Williams, the only non-white player on the '95 Springboks. Even in Paarl I was told that people were cheering for Williams but rooting against the Springboks.

One of the most surprising and memorable scenes of the tournament arrived after England had beaten defending champion Australia in overtime on a drop-goal from 45 meters by Rob Andrew. That's the equivalent of a 49-year field goal -- but in Andrew's case he drop-kicked it in the flow of the game, the way Jim Thorpe used to do it.

When the match was over, and England had beaten Australia for the first time outside the northern hemisphere -- its first "away'' win -- the English writers in the press box all glanced among each other, then stood up and applauded. That part blew me away. The rule in the U.S. is no cheering in the press box, not even when the U.S. upset the Soviets in the 1980 Olympics at Lake Placid. But it wasn't like they were all jumping up and down and cheering; this was sober, nodding applause, in acknowledgement of the effort as much as the result. I looked at the writers standing all around me and realized there was a lot more for me to learn than the laws (that's how they refer to the rulebook) of rugby.

The biggest star of the tournament was 6-5, 275-pound Jonah Lomu of tournament favorite New Zealand, which would meet the Springboks in the final. Lomu had made only two appearances for the All-Blacks, but his speed and explosive athleticism made him his sport's newfound Shaquille O'Neal -- "a freak,'' according to England captain Will Carling. In fact, there were scores of freaks like Lomu playing college football in the U.S., and I've always wondered why rugby hasn't recruited those who can't find jobs in the NFL.

The New Zealand coach would claim after its 15-12 loss in overtime to the Springboks that more than half of his players were suffering from food poisoning in the 48 hours before the final, amid allegations of bugging devices in their rooms and car alarms being set off outside the hotel on the eve of the big game.

During the pregame ceremonies, a South African Airways 747 flew twice over the downtown stadium. It came extremely close to hitting us, and my first thought -- years before 9/11 -- was that we were all going to die. Then I thought about what Mandela must have been thinking: I overcame a murderous government, I survived 27 years in their prison and this is how it ends for me -- in a Springboks jersey. But, of course, the authorities had agreed to the flyover beforehand.

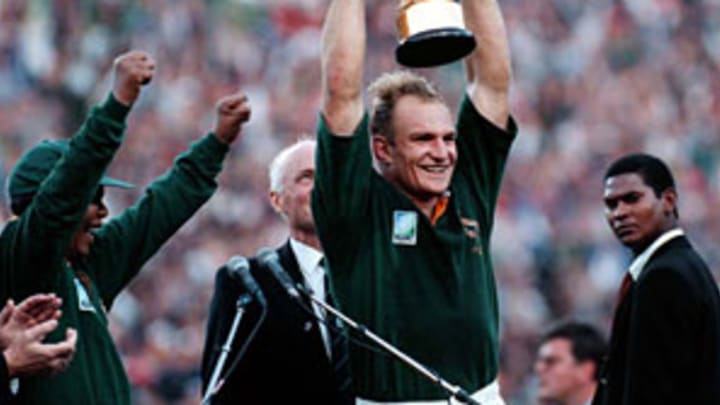

Mandela's positive influence was undeniable. When he walked into the dressing room before the game wearing Pienaar's No. 6 jersey and a matching green cricket cap, he galvanized the players by convincing them they were indeed playing for their country. He had a similar impact on the overwhelmingly white crowd when he appeared on the field in Pienaar's shirt. The Springboks gang-tackled Lomu and patiently acquired points on the kicking of Joel Stransky, who converted the winning drop-kick from 30 meters in OT. Mandela was wearing his Springboks green when he presented the trophy to Pienaar.