Losing 20 games isn't for faint of heart, or game's worst pitchers

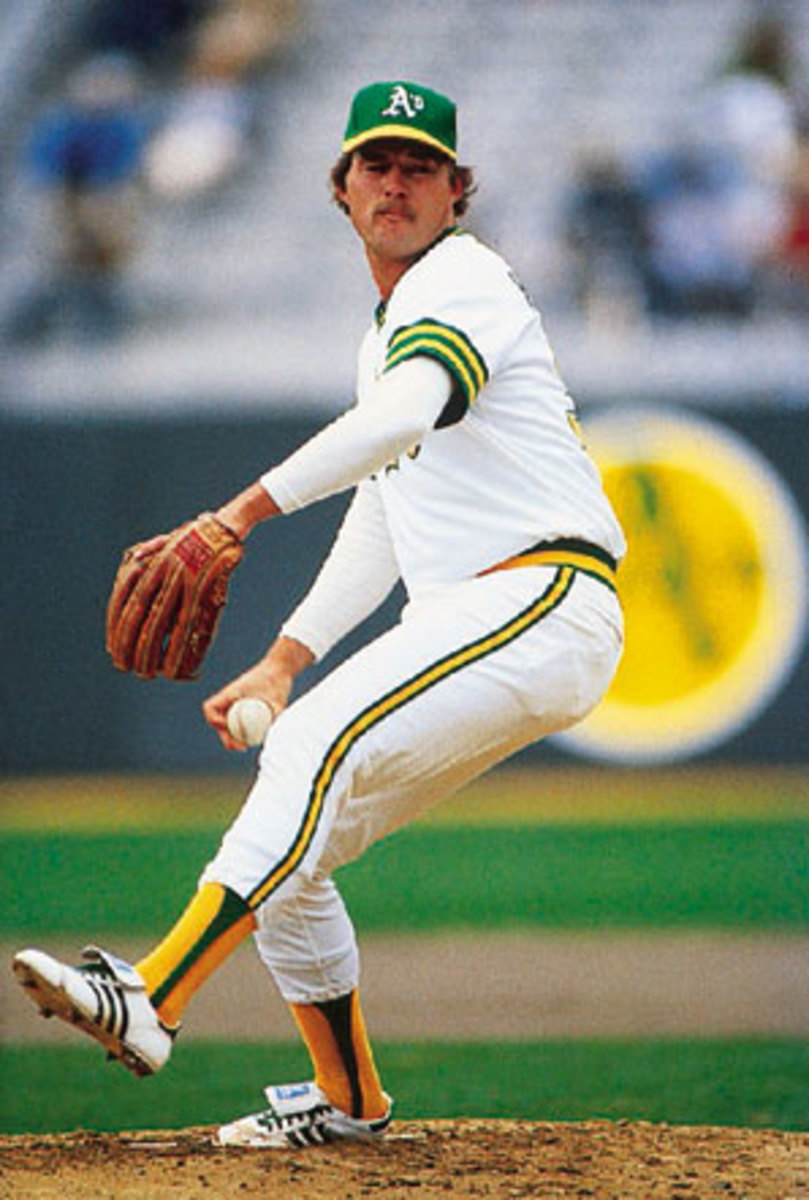

For more than two decades people remembered Brian Kingman as the last man to lose 20 games. That dubious distinction was his for an 8-20 record while pitching for Oakland in 1980, and though it would have been perfectly understandable if he had wanted to put distance between himself and his record, something else grew to be true, too:

At least people remembered Brian Kingman.

"I feel sorry for those guys who get all the way to 19 -- they might as well take the final step and lose 20 because [they have] all that frustration and then never be talked about," Kingman said.

For 23 years, any time a pitcher approached 20 losses Kingman's name would appear as a recurring note, often preceded by the words "not since." During that time he embraced his baseball identity with a good-natured sense of humor, and while most fans and players can tell you about wins and strikeouts and hits and homers, Kingman can tell you about losing.

He also helped perpetuate his place in history. In fielding phone calls from reporters any time a pitcher approached 20 losses -- this year it's Baltimore's Jeremy Guthrie who lost his 17th on Sunday -- Kingman gained a near encyclopedic knowledge of his 1980 season and the company he now keeps, answering questions with a quick wit.

He can tell you his run support from that 1980 season to the 10th (2.9), how many times a pitcher has lost 20 games (499), how many consecutive 20-loss seasons Pud Galvin suffered in his 19th century Hall-of-Fame career (a record 10) and even the closest a man has come without losing 20: In 1952, Detroit's Virgil Trucks went 5-19, twice staving off a 20th loss by throwing no-hitters in 1-0 games. (Trucks also threw a one-hit shutout in a third 1-0 complete-game win.)

The name on Kingman's e-mail address is a tribute to Galvin, and he used to travel cross-country to watch prospective members face initiation into the 20-loss club, even attempting to ward them off with a voodoo doll.

Yes, a voodoo doll. Kingman's is quick to note that his wife, who's from Louisiana, doesn't really believe in voodoo and even quicker to note that he definitely doesn't believe in it because she obtained the doll while his losses were mounting back in 1980. "This proves it doesn't work because I lost 20," he quipped.

But that didn't stop Kingman from bringing it along for a few trips to watch potential 20th losses. The traveling began on a dare from a friendly Philadelphia sports writer who urged Kingman to attend a start being made by the Phillies' Omar Daal in September of 2000, when Daal was 3-19. Kingman showed up, and Daal got a no decision. Five days later, Kingman traveled to Chicago for what would be Daal's final start of the season, and this time he won.

The first four times Kingman made such trips, the pitcher with 19 losses failed to lose his 20th in each. That streak finally ended on Sept. 5, 2003, when Mike Maroth, pitching for the eventual 119-loss Tigers, lost his 20th game in Toronto.

"I ended up out of the country, and my powers were weakened," Kingman said with a laugh.

Kingman, of course, is the exception. Not everyone is as enthusiastic about his place in history, including the man that supplanted Kingman as the most recent 20-game loser. Maroth went 9-21 with a 5.73 ERA in 2003 and makes it clear: "That's not what I want to be remembered for."

"It was not fun to go through," Maroth said, "but coming through the other side I was able to learn about myself and the accomplishment of just fighting through it and to know that I never really gave in. Every time I was called to pitch, I went out there and I kept going."

Many pitchers, like Maroth, have been given the opportunity to shut down their seasons early to avoid the ignominious No. 20, but he chose to keep pitching, admirably making five more starts after his 19th loss, including the start when he lost his 20th, which came soon after his grandmother passed away.

"I didn't want to let my teammates down," Maroth said of not prematurely ending his season. "I wanted to continue going out there and give everything I had."

Losing 20 games is not for the faint of heart. And it's not for the game's worst pitchers. For a pitcher to lose 20, there must be a delicate balance of conditions: He can't be so good that he's winning games on his own, while he can't be so bad that he loses the faith of the manager and front office, plus the offense can't provide meaningful run support. A 20-game loser must be good enough that the team wants to continue giving him the ball. Kingman and Maroth were both in their first full major-league seasons, yet weren't returned to the minors for more seasoning.

Maroth, for instance, rebounded in 2004 with an 11-13 record and 4.31 ERA for a 90-loss Tigers team, including a one-hit, complete-game shutout of the Yankees. In 2005 he won a career-high 14 games, finishing a three-year stretch of remarkable durability, as he made 100 starts and threw 619 1/3 innings. He wasn't an All-Star or even that close to one.

Eventually, surgeries to his elbow, shoulder and knee quickened the end of his career. He last pitched in the majors in 2007 and finished his pro career with the Twins' Triple-A affiliate in 2010 before retiring this past January.

Kingman, meanwhile, pitched for the Billy Martin managed A's teams of the early 1980s where a complete game was practically required; the staff threw 94 in 1980 alone, the majors' most since 1946. Kingman completed 10 of his 30 starts in his 8-20 season -- and made quality starts in 16 of his 30 outings -- but his arm wore down, and he went 7-18 over 227 2/3 innings with a 4.31 ERA over the next three seasons.

Losing 20 used to be commonplace when starters typically made more stats and pitched deeper into games. There's no minimum number of innings needed to receive a loss the way there is for a win, but pitching deeper into games creates more opportunities for a starter to have a bad inning in which he gives up multiple runs or to lose a tie.

In 78 years from the start of the World Series era in 1903 until Kingman's 1980 season, there were 187 instances of a pitcher losing 20 games, an average of 2.4 per year. Fourteen Hall of Fame pitchers had a 20-loss season in the 20th century, including, as Kingman learned on a sports highlight show, such luminaries as Cy Young and Walter Johnson.

"I figured," Kingman recalled, "'Hey, that'd be like if you were a scientist getting linked to Einstein or something -- I was being mentioned with Cy Young and Walter Johnson.'"

What's unique about Kingman's 20-loss season is that it happened for an A's team that had a winning record, the first time that had happened since the Reds' Dolf Luque in 1922. Oakland was 83-79 in 1980, meaning Kingman had more than a quarter of the team's losses despite a respectable ERA of 3.83, which, when adjusted for the league and ballpark, became a 98 ERA+, meaning it was just two percentage points below average -- hardly deserving of 20 losses.

Kingman gleaned this wisdom from that experience: "Winning is circumstantial." Indeed, win and loss records can be fickle, depending on a pitcher's defense and run support.

The glaring example he likes to give is that in Bob Gibson's historic 1968 season when he had a 1.12 ERA, his record was only 22-9. "How did he lose nine games?" Kingman asked. Indeed, Gibson gave up three or fewer earned runs in all nine losses; only twice did he allow four earned runs, and in those starts he got a win and a no decision.

Perspective on wins and losses in baseball has changed dramatically in the last few years. Three of the last four Cy Young winners had just 13, 15 and 16 wins. That number under the 'W' and 'L' may make for interesting baseball-card reading but not for examining a pitcher's effectiveness. It's a lesson the 20-game losers learned earlier than most.

"They put the wins and losses next to a pitcher's name, but it takes a lot more than just that pitcher to get those wins and losses," Maroth said. "You can't look at a guy who has 15 wins and say that he pitched 15 great games."

Maroth has returned to his native Orlando, where he and his wife have three children. Maroth is honest and forthright in acknowledging the 20-loss season on his Maroth Baseball website, which he uses to advertise his private pitching instruction services. This spring will also be his first year as head baseball coach at Foundation Academy, a nearby private high school.

Kingman previously owned a check-cashing company and now works for a distribution company in Phoenix. He recently returned to playing baseball in an area men's league. His fanaticism for tracking pitchers closing in on 20 losses has dissipated. He said he won't travel if Guthrie gets to 19.

"But I probably keep closer tabs on it than virtually anybody," Kingman said, "because who keeps track of losses?"