How one draft decision changed fortunes of two NBA franchises

"Life is funny," says Sidney Moncrief. Only by "funny," he doesn't really mean funny. He means weird. Strange. Quirky. Unpredictable. "One decision -- any decision -- can change everything."

Moncrief chuckles, because there's nothing grave here. This isn't a column about a man who didn't show up for work on September 11, or a child pulled from a fire. It is, instead, the simple, seemingly insignificant tale of a long-ago choice made by the Los Angeles Lakers and the Milwaukee Bucks.

A choice that forever changed Moncrief's life.

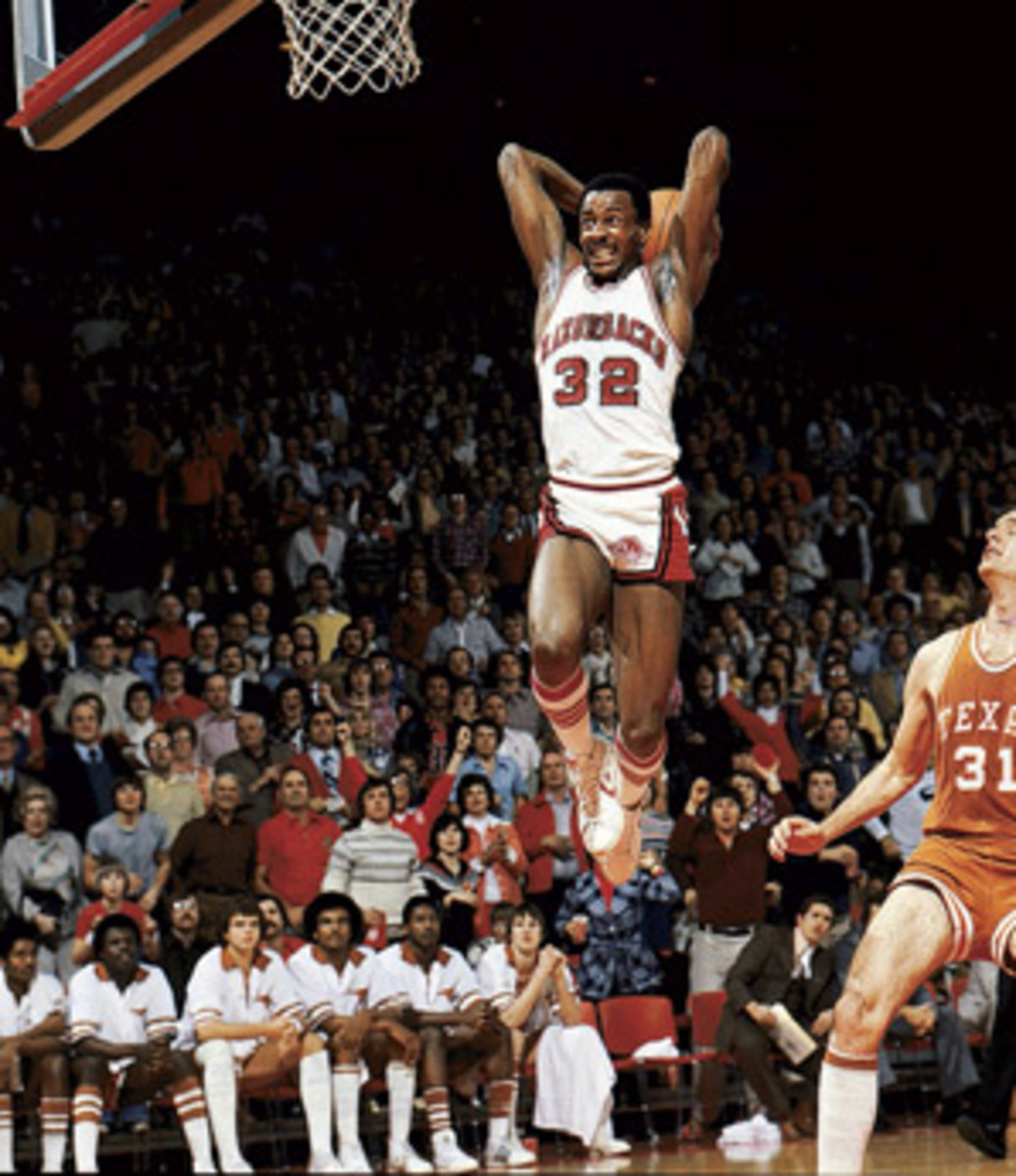

In the weeks leading up to the 1979 NBA Draft, the Lakers -- owners of the first pick -- were more torn than, in the ensuing decades, they've ever let on. There were two magnificent college players on their board; players with myriad skills, loaded resumes and franchise-changing potential. One was a high-flying 6-foot-4 guard out of the University of Arkansas named Sidney Moncrief. The other was a transformative 6-9 guard out of Michigan State named Earvin Johnson. People called him "Magic."

Moncrief was everything a pro team would want in a player. He was polished beyond polished; lightning-quick, a dead-eye shooter with a Walt Frazier-esque first step and an eagerness to play tenacious defense. The Los Angeles Times' Ted Green compared him -- rightly -- to David Thompson. "He was a terrific basketball player," says Paul Westhead, who would eventually coach the Lakers that season "You could watch Sidney Moncrief play and know he had a lot of tools."

And yet ... Johnson was the first of his kind -- a power forward-sized point guard who could dribble, pass and rebound with aplomb. Why, there was only one question about the kid -- though, admittedly, a big one: Could he shoot?

As the draft drew closer, Lakers general manager Jerry West debated Johnson-Moncrief with anyone within sight. Though he has been reticent to admit it, West leaned toward the gunner from Arkansas. The Lakers already had Norm Nixon, a top-shelf point guard who had just averaged 17.1 points and nine assists in his second NBA season. The idea of two stars playing the same position made little sense.

So, Moncrief it would be.

No, Johnson.

No, Moncrief.

No, Johnson.

No ...

"Honestly, I didn't have a strong preference," says Moncrief. "Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, Los Angeles and New York all expressed interest, and only L.A. was warm. So I guess that was preferable. But, really, I just wanted to be drafted."

Of course, we all know how this turned out. Under the directive of Jack Kent Cooke, the team's outgoing owner, Los Angeles went with Johnson's larger-than-life persona and proceeded to have one of the great runs in NBA history. Moncrief, meanwhile, fell to the fifth pick, where Milwaukee swooped him up. He became a five-time All-Star, as well as one of the finest players in franchise history.

He was, alas, no Magic Johnson.

"If you ask me what would have happened had the Lakers taken me, I'll be completely honest," he says. "Maybe we win a championship, but there's no way the Lakers do with me what they did with Magic. That team needed one guy to get everyone to play together, and he was it. There's a reason Magic Johnson goes down as one of the great players. He could do everything."

There is nary a hint of bitterness or envy in Moncrief's words. Upon retiring from the NBA after 11 seasons, he returned to Arkansas to pursue a career in private business. He coached one season at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock, another season with Ft. Wayne of the NBA's D-League, and endured several years as Don Nelson's defensive guru in Dallas and Golden State. Now he is back home, serving as a first-year assistant to Scott Skiles in Milwaukee. Every time he arrives for work, he gazes upward inside the Bradley Center and sees his jersey in the rafters. Sometimes he thinks back to his greatest days as a Buck. Every so often, his mind even flashes to 1979; to what could have been.

"It's a beautiful thing, how people still remember me here in Milwaukee," he says. "I gave a lot to the Bucks, and this city gave a lot to me. I'm glad the way things worked out, because who knows how it would have worked in Los Angeles?

"Here, in Milwaukee, I belong."