Chamberlain's 100-point game proves some things better with age

Dave Zinkoff -- or simply: The Zink -- was perhaps the most distinctive public address announcer in sport when, years ago, he called games in Philadelphia --especially for the city's NBA teams. Just his declaring that there were two minutes left in the quarter made you feel that never mind that quarter -- doomsday was but a 120 seconds away.

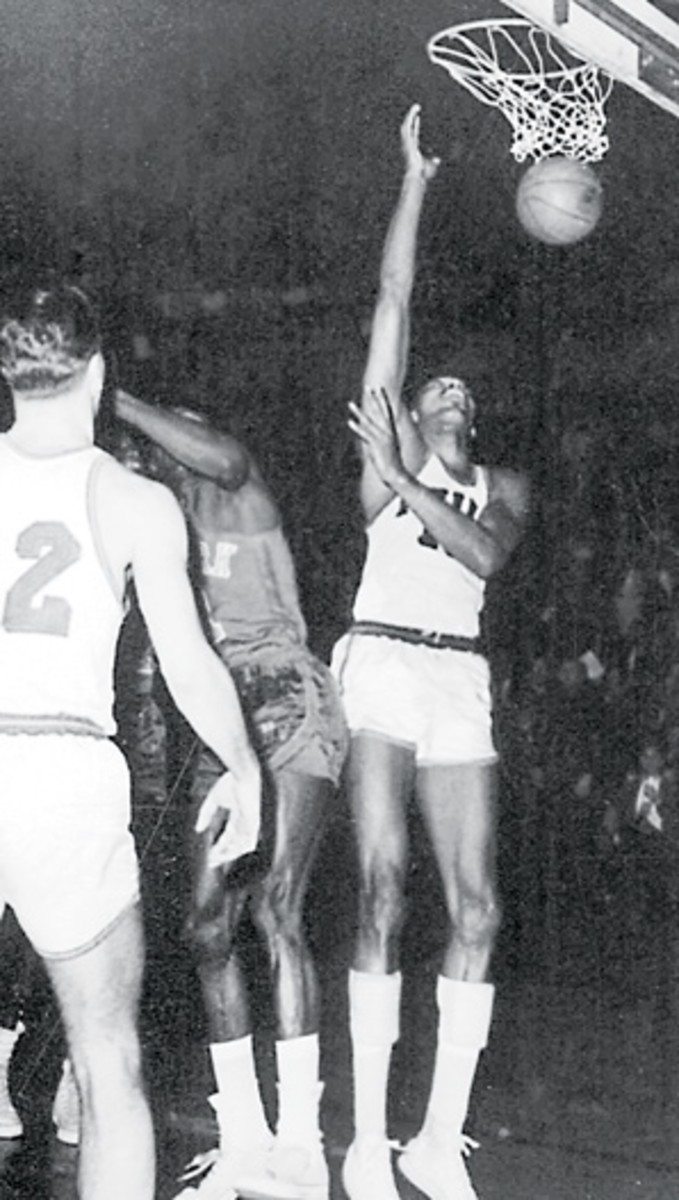

But nothing The Zink cried out was so resounding as when Wilt Chamberlain would make an emphatic slam. "Dipper dunk!" he would holler.

And so it was exactly 50 years ago on March 2 when The Zink was there in an old hockey arena in Hershey, Pa., screaming "dipper dunk" again and again as Wilt Chamberlain was on his way to scoring 100 points.

It's often difficult to measure the quality of an individual achievement in a team sport. Yes, on that March 2, 1962, Wilt's Warriors were playing the Knicks, at the time the worst team in the league, whose starting center was injured, in a meaningless game; but still and all: 100 points in any game in the NBA! In all of Division I college ball, only one guy has gone for a century and that was Frank Selvy of Furman University ... and that was in 1954 -- 58 years ago.

Yet curiously Chamberlain's accomplishment needed time to become accepted for the wonder that it is. There were maybe four thousand people in attendance, and many of those had primarily come to see members of the Baltimore Colts and Philadelphia Eagles scrimmage at basketball in the preliminary. Chamberlain averaged 50 points a game that season, and his act seemed old. Scoring 100 points didn't even merit the front-page in New York newspapers, and didn't evoke much more attention in the Philadelphia dailies. Chamberlain was often dismissed as just a "goon," as tall players were called then.

The greatest public certification you could receive in 1962 was to be invited to appear on the "Ed Sullivan Show" on CBS. Chamberlain was accorded that honor, but unbeknown to him, only to be made a fool of, when a dwarf named Johnny Puleo was assigned to run out and pretend to bite the giant's leg. Scoring 100 points? The audience only roared, mocking the big freak.

How ancient that game seems now: no TV, barely a photograph. The Warriors' publicity man, Harvey Pollack, scratched out the number "100" on a piece of paper, Wilt held it up in the locker room, and that primitive picture is about all we ever see from the game. I was with Chamberlain a couple of times, years later, when pandering fans would come up and tell him they saw him score the 100 ... in Madison Square Garden. Chamberlain didn't bother to call them out. "Thank you, my man," he would politely reply.

History isn't even sure how he scored the 100th point. Wilt was so strong he was afraid of hurting opponents. He really didn't slam the ball down all that much, generally preferring the dainty---- what was called his "finger roll." Some witnesses remember that he took a pass and merely laid the last basket in. Others swear it really was The Zink screaming "Dipper dunk." Imagine not knowing about the ultimate basket in basketball.

But then, it was, after all, so very long ago when the late Wilt Chamberlain scored 100 points in an NBA game in Hershey, Pa. Even in sport, some things get better with time.