Montana's Lloyd Woodard looks to build on Bellator breakthrough

While Friday nights have yet to become a prosperous destination for both The Ultimate Fighter Live and Bellator Fighting Championships on cable television, there are still small victories to be had beyond ratings numbers.

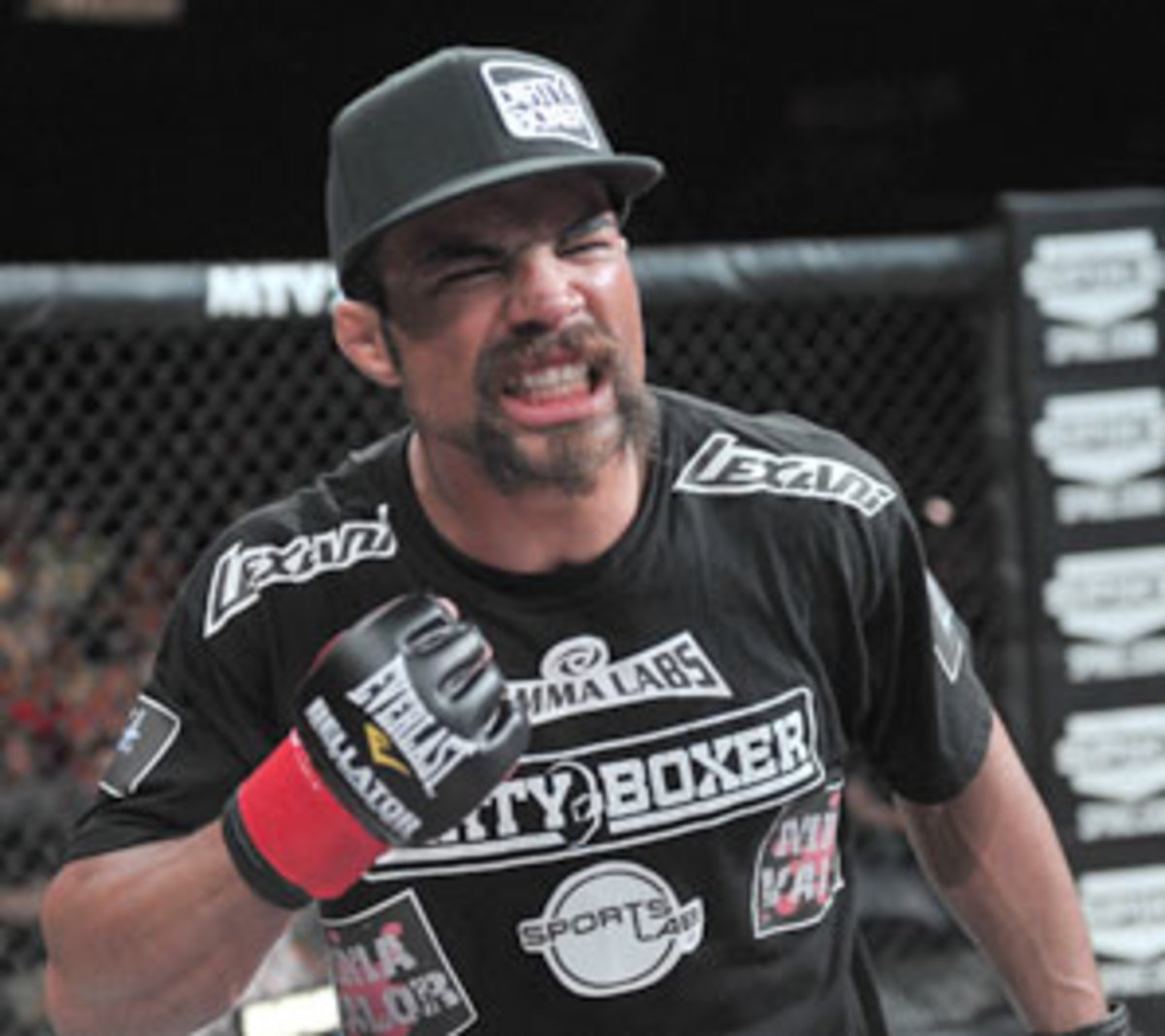

Just ask Lloyd "Cupcake" Woodard.

The Washington-born Montanan went from an unknown to full-on MMA media darling this week by submitting Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belt Patricky "Pitbull" Friere in a Bellator lightweight tournament quarterfinal bout in Laredo, Texas.

This has to be considered a win for Bellator, which drew 175,000 viewers for its four-fight live event on MTV2 to the 1.2 million who tuned into FX for the half-taped, single-fight reality series now in its 15th season.

It's obvious that the enthusiastic Woodward, with his Yosemite Sam-esque mustache and guns-a-blazing striking style, connected with his audience. On Monday, media members wrote and talked about Woodard more than Urijah Faber and Dominick Cruz's flip-flopping rivalry featured in last week's TUF episode.

For Bellator, still nine months away from its big move to Spike TV and the significant ratings boost that should come with it, a fighter like Woodard -- who fans will care enough about to tune in and watch again -- is worth his weight in gold. It's fighters like Woodard, the small-town guy making good, who will help Bellator resonate more with a fanbase that's grown accustomed to one dominant brand.

The 27-year-old Woodard, a self-professed "mountain man" with a checkered past, wasn't expected to get past favorite Friere, who'd stormed through the promotion's previous 155-pound tourney before dropping a decision to future lightweight champion Michael Chandler in the finals last May.

Woodard admitted he had no true strategy going in other than "to scrap," but like Chandler, he kept the pressure on and answered each of the ultra-aggressive Friere's punches with his own. After a close first round, Woodard clipped the shooting Brazilian with a knee halfway through the second to gain superior positioning and the fight-ending kimura.

"Every time I got hit, I wanted to hit him back harder," Woodard said. "Right before I submitted him, he threw a really clean knee to my body and it hurt me, but I was so mad that I stayed in his face and swung back at him even harder."

Woodard made $20,000 for the quarterfinal bout, including a $10,000 win bonus, and couldn't have been more elated about it. It was far more than he'd ever been paid during the 10-0 run he amassed off the beaten path in states like North Dakota and Washington when he went pro in 2008. Back then, Woodard, gratefully took fights for $100 just to get the bookings. He knew, at the very least, they were steps a positive direction.

The third youngest of nine children, Woodard had already sampled what his life would be like if he'd ventured the other way. Woodard's parents had divorced when he was two years old and he and his siblings were bounced between relatives' homes in Washington, Memphis, and Kentucky for much of their childhood. Woodard's father, a truck driver, was on the road most of the time.

In South Memphis, Woodard learned to defend himself early on. He was on the only biracial kid in his class, and had a slight speech impediment he didn't grow out of until high school. The other students called him "white boy," hit him with the hard, plastic cafeteria plates and told him he smelled because he owned only three outfits.

"I got beat up quite a bit," Woodard said. "Sometimes I got jumped. The only thing I had going for me is I'd watch pro wrestling with my grandma all the time. I could headlock them and hold them down on the ground until, hopefully, somebody would come to help me."

At age 13, Woodard was sent to Alaska to live with his mother. They settled in Montana, but by then, the survival skills he'd cultivated in Memphis were ingrained in him.

Woodard wrestled in high school and competed in a few amateur MMA fights after that, though these weren't the actions of a young athlete looking to better himself.

"At the time, all I wanted to do was be the toughest guy ever with the most perfect grill, who drank whiskey and partied all the time and was the center of attention," said Woodard. "Those were the things I thought were important."

Poor choices followed.

At age 19, Woodard voluntarily accompanied his best friend to an apartment, where his friend planned to physically confront another guy and his basketball teammates over an earlier dispute. Woodard had been drinking that day and thought nothing of "backing up" his friend, though when they got there, the guy was alone. Woodard said he was talking to the guy's girlfriend when his two friends jumped the guy.

"It happened in a matter of seconds. I didn't see it with my own eyes," Woodard recalled. "The kid was laying on the floor against the kitchen sink with blood coming out of his mouth. I think he had to have his jaw wired shut."

When an ambulance was called, Woodard and his friends fled the scene. Woodard said he hadn't thrown a single punch himself, but he hadn't done anything to stop the beating either.

"I didn't treat that guy as a human being, just like the kids who'd beat me up when I was a kid," Woodard said. "I'd turned into what they'd been."

Woodard was convicted of felony burglary, but it didn't deter him. When he was arrested for additional altercations, Woodard's probation was revoked and he was sent to the Missoula County Jail, which housed about 400 inmates. Woodard was behind bars for the next 13 months.

"I didn't have any problems in jail," said Woodard, who spent a lot of his time reading, watching television and thinking about where it had gone wrong. "I didn't have to join any gangs or get tattooed up. I didn't get bothered with. That's what I like about Montana. It's a great state with good people here -- even the people in jail have a common respect for each other."

Woodard was then transferred to the state's Correctional Training Center, which ran a "boot camp" out of the prison. Woodward stayed there for four months and spent another five months in an after-care program.

"I had a lot of growing up to do," Woodard said. "I was a Montana boy who made the wrong decisions at an early age. I was incarcerated for pretty much two years of my life and during that time, I realized I was meant for doing something else."

When he was finally released, Woodard vowed to never again squander the control he had over his life. However, it was a chance meeting a few months later with Adrienne Noel, a fitness model and ski patrol woman who he'd dated in high school, that gave Woodard motivation and direction.

"After we reconnected, that was the point in my life that I realized I had someone that loved me so much, who I loved so much back," Woodard said. "I wanted to be a better person for her, for myself. Today, there's nothing left in me that reverts back to that old person."

The only remnant Woodard kept of his former self was his penchant for fighting, something he'd discovered out of necessity that he now hoped to parlay into a serious career. In Missoula, Woodard met Matt Powers, a local businessman who helped fund the beginnings of what would become the Dogpound Fight Team.

At Woodard's first professional fight in 2008, Powers wanted to give him the nickname "Pretty Boy," but the fighter didn't want to take a moniker made famous by Floyd Mayweather. In a spur-of-the-moment decision, Powers wrote down "Cupcake" on the announcer's form.

It was a joke, of course, but Woodard got a kick out of it.

"When my opponent got beat up by a guy named 'Cupcake,' it was pretty funny," he said. "I hope it catches on to the point where people will say that guy's a 'bad cupcake.'"

Woodard's 10-0 streak got him onto Bellator's radar in 2011. He beat Carey Vanier in his debut for the promotion that March, then suffered his first career loss to future champion Chandler a month later. The defeat convinced Woodard to venture out of Montana for his training for the first time; something he'd been hesitant to do to in the past out of his fierce loyalty for his coaches, team, and state. Woodward spent a month with Olympic wrestling medalist Matt Lindland's Team Quest in Oregon last summer and plans to return at some point to train there again.

In the meantime, Woodard's two crowd-pleasing performances were enough to earn him a slot in this season's lightweight tournament. On April 20, Woodward will face 2004 Olympic judo qualifier Rick Hawn in one of the tournament's semifinals in Cleveland, Ohio. With Friere eliminated, Hawn is widely considered the stiffest competition left in the brackets.

Again the underdog, Woodard relishes in the idea of facing Hawn next, as the tournament winner will get the opportunity to later face Chandler, the one blemish on his record.

Woodward's recently learned that his 65-year-old father will go to prison soon for drug trafficking, an unnecessary reminder that one's life can go astray at any time with just one bad decision.

But right now, there's only one direction in Woodard's life and that is forward.