Barboza made long, improbable journey from slums to octagon

Edson Mendes Barboza Jr. never minded being called a "prodigy."

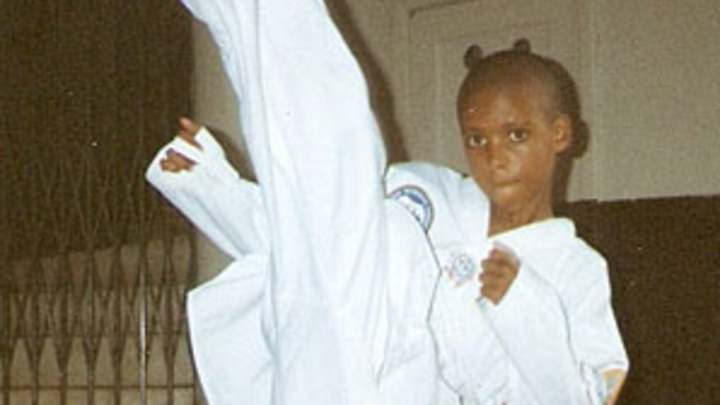

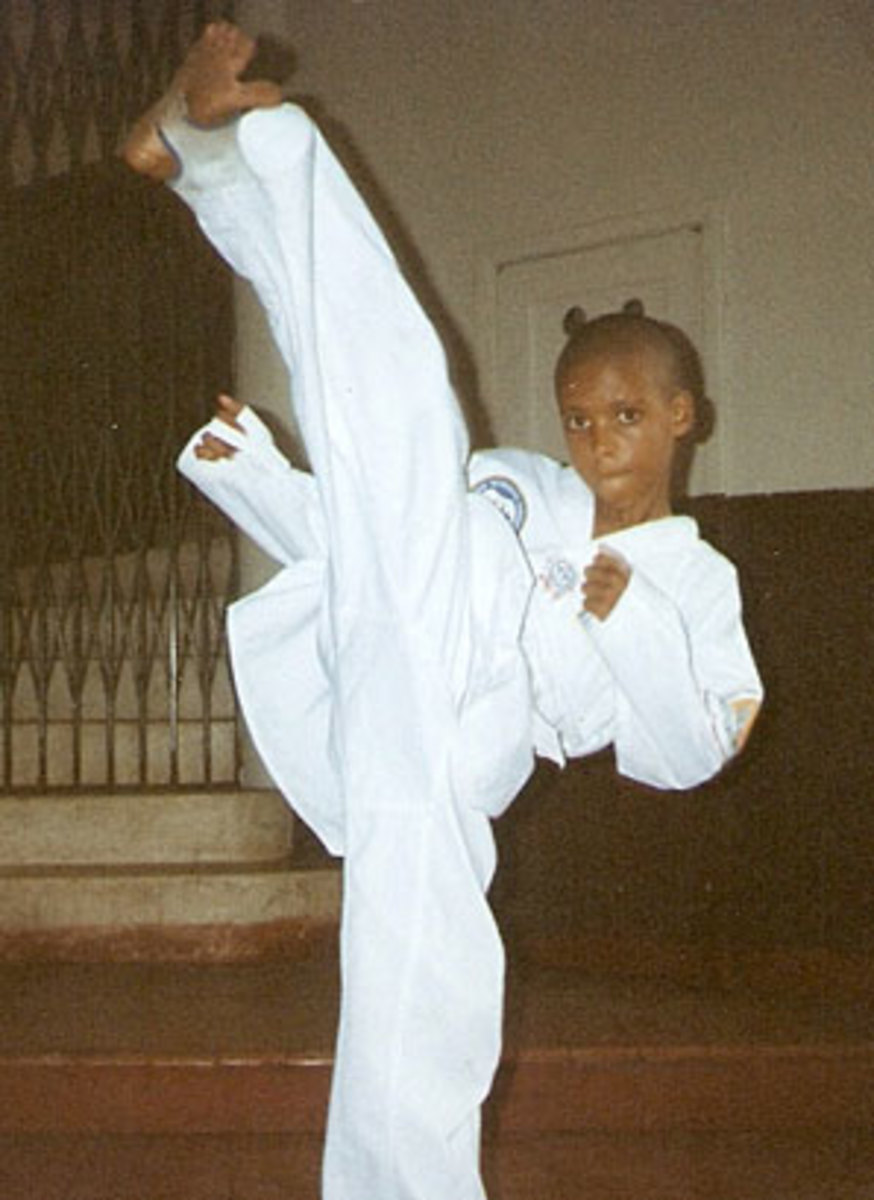

He's worn that label as easy as a pair of gloves since age 8, when he began kickboxing through a social project for underprivileged children in his favela.

From the slums to Las Vegas, the lethal lightweight striker makes his fifth octagon appearance this Saturday against former WEC champion Jamie Varner at UFC 146.

The fans are expecting fireworks. Barboza's last fight went viral after he nearly decapitated Brit Terry Etim with a spinning wheel kick, a rarity if not a debut of the finishing move on the sport's biggest stage. The knockout will be tough to top, but the 26-year-old Barboza (10-0) knows a thing or two about expectations.

Born three months premature in Nova Fibrugo, just outside Rio de Janeiro, "Junior" first surpassed expectations simply by surviving.

"The doctor came to his mother and told her only one of them was going to live. He said he couldn't save both of them," said Joe Mullings, Barboza's U.S. sponsor. "Junior's father told him to save his wife, and despite that, he lived."

In the family's simple single-room dwelling, Junior's first bassinet was a shoe box. Years later, when Junior, his parents, and his older sister moved to a "bigger" house in the favela no larger than 20 by 20 feet, an 8-year-old Junior would sit with his father to watch tapes of the IVC (International Vale Tudo Championship), a local MMA event inspired by the UFC.

When the opportunity came around for Junior to train kickboxing, he'd finish school at noon and ride his bike to the gym three days a week. On the other days, he'd return to the gym alone to kick the bags for hours, and his fast, explosive athleticism quickly separated him from the other children. Three years later, Junior began biking 30 minutes each way to train with Anderson Franca, one of the country's most renowned muay Thai coaches.

Coming under Franca's tutelage wasn't something taken lightly by Barboza's parents. His father worked as a metallurgist in the local mining industry and his mother at a day care, but Junior was forbidden to get his own job to help support the family.

"I told my parents I wanted to work, I wanted to help, but they told me the best way I could help was to continue my studies and training," said Barboza through Mullings' translation.

Despite his parents' best intentions, they couldn't prevent their prodigy son from falling in love. At 17, Barboza first saw Bruna Almeida training at the Fight Company, a gym they both frequented. Almeida was a budding MMA journalist for Brazil's perennial Tatame magazine.

"I didn't think I had a chance," said Barboza. "She was from a family of means, with a much better education. She was a journalist. She had a profession. I came from a favela."

Bruna's brother, one of Barboza's good friends, talked her into walking over to him.

"My brother told me I was about to meet the man of my life," she said. "All the girls wanted to date him; he was very good-looking. I liked him because he was a very calm person." They began dating shortly after, as Barboza continued to rack up dozens of regional and national muay Thai titles.

In 2003, longtime MMA manager Alex Davis watched Barboza fight live for the first time. Davis knew all about Barboza already; Franca was his son-in-law and spoke of him often. Plus, Barboza had earned a name for himself around Rio, where muay Thai had a strong competition circuit and following. Ironically, Barboza lost for the first time in his career that night, but his talent and competitive maturity couldn't be denied.

"From the beginning, you could see he had something that can't be taught," said Davis, who co-manages Barboza with Mullings.

By 21, Barboza had collected a 25-3 record, with 24 wins by knockout. His crowning moment came when he won the Demolition Fight grand prix that year. Barboza took his prize of 10,000 reals (about $5,000 in U.S. currency today) and bought his family their first car: a used, dark blue Volkswagen Gol. Before that, the Barboza family had transported Junior's ailing 78-year-old grandfather to the hospital three times a week by bus.

Barboza's next move would have been to fight in Japan's K-1 MAX, the international promotion's sister event for lighter strikers. But when American Top Team sued the promotion, Davis (who was affiliated with ATT) said the organization took it out on Barboza and wouldn't book him.

"In that moment, I knew we didn't have a future in kickboxing," he said. Davis, who steers the careers of other successes like UFC heavyweight Antonio "Big Foot" Silva, and his son-in-law Franca sat down to weigh Barboza's future. It was decided that he'd be sent to Mulling's Florida gym, The Armory, to pursue MMA.

"This decision caused conflict within my family," said Davis. "My son-in-law wanted to take Junior all the way in muay Thai and we almost came to blows over it. Only now, he sees it was the right choice."

The decision didn't come without sacrifice. Barboza had to leave his family and girlfriend Bruna behind. In January 2009, Mullings and Armory head coach Eduardo Guedes collected Barboza at the Miami Airport.

"We see Edson come out through the international arrivals and all he has is this little pack, not even a backpack. Just this little pack. I said, 'Let's go get your luggage,' and he said, 'No, this is all I have.'"

Mullings and Guedes took Barboza straight to the academy, where fighters were putting in their evening training sessions. Mullings watched Barboza survey the room, then reach into his pack.

"He takes out gloves and some old, beat-up hand wraps, wraps his hands, and starts training with everybody," said Mullings. "After a while, nobody wanted to get into the cage with him anymore."

Four months later, Barboza won his first MMA fight by technical knockout in a local promotion.

"Talent usually doesn't like to work," said Davis, "but once Junior got kickstarted, we saw what someone with talent can do. Joe has done a great job teaching him how to work. Junior practiced hard for muay Thai; he practices even harder for MMA."

During Barboza's first year as a mixed martial artist, Mullings and Davis were able to get him to a 6-0 record, as coaches developed and drilled the fighter's wrestling and ground game. However, word of the Brazilian's extensive striking background quickly dried up prospects on the local circuit.

Zuffa, the promotion that owns the UFC, had seen enough, though. In the summer of 2010, with Bruna now moved to the States by his side, Barboza was signed to a multi-fight contract and made his debut against Mike Lullo at UFC 123 that November, winning by third-round TKO.

"Junior's original contract, for not coming from a major promotion, was generous. I'll leave it at that," said Mullings. "And we've since renegotiated another generous contract that we're two fights into now."

Barboza's "elegant violence" has also attracted substantial sponsorship money, according to Mullings, reaching north of $40,000-$50,000 a fight before commissions.

"You can't finish a fight in a second with a submission or as a wrestler," said Mullings, who outsources Barboza's sponsorship to VF Elite's John Fosco.

Additionally, Barboza has banked an extra $300,000 in incentive bonuses for his last three UFC victories. Barboza won two bonuses -- for fight and knockout of the night -- against Etim at UFC 142 in January.

The added cash flow hasn't been squandered, though. Barboza lives in a modest apartment around the corner from the gym with wife Bruna (they married in 2010 at city hall), who doubles as his publicist. He's traded in his bicycle for a BMW 325ii convertible -- the one, big splurge he's allowed himself until he reaches a personal goal.

"My dream is to buy my parents a new house and I'm pretty close to that," said Barboza, who's forced to curl up his 5-foot-11 frame to sleep when he visits home because his bedroom no longer fits him.

As a competitor, Davis and Mullings said the religious, kindhearted Barboza possesses a focus and discipline that can only come from years of experience.

"Nothing rattles him. I haven't seen him come undone once," said Mullings. "The week of weight-cutting, you can get right down to the core of who that fighter is. Everyone comes undone one time or another, but not Junior. I've seen him not eat a single calorie for 36 hours, delayed at the airport for hours waiting for luggage and he doesn't even flinch."

But Barboza's true exceptionality comes in the cage, said Davis.

"It's a Muhammad Ali type of talent," said Davis, who watches Barboza set up kicks like the Etim assault two or three moves before his opponent knows what's coming. "He's a genius, not only at muay Thai, but in whatever he puts his mind to. He's special."