Despite close calls, Padres only members of the no no-hitters club

Among the reasons why the San Diego Padres have never had a no-hitter in any of the 6,904 games comprising their 43-plus seasons in the major leagues, the biggest ones are probably bad pitchers and bad luck. But for the man who came closer than any other single hurler in franchise history to achieving the feat the real reason is bad managing.

"I should have had my no-hitter," says Steve Arlin. "It was stupid how I lost my no-hitter."

On July 18, 1972, Arlin, a part-time dentist who occasionally did emergency work on umpires arriving in San Diego with toothaches, carried a no-hitter through 8 2/3 innings against the Phillies. With a 5-0 lead and one out to go in the top of the ninth, he got two strikes on Philadelphia's Denny Doyle.

That's when first-year Padres manager Don Zimmer thought Doyle, a lefthanded hitting second baseman, was going to bunt. Zimmer signaled from the dugout to have third baseman Dave Roberts move up about eight feet on the grass.

Doyle, connecting on an inside slider, hit a ball that bounced over Roberts' head -- a ball that he would have been able to field had he been playing in his normal position. Padres shortstop Enzo Hernandez couldn't make the play.

Arlin gave up a hit to the next batter, too, before closing out the 5-1 win. To this day, he's still ticked about it.

"It was a case of Zimmer over-managing,'' Arlin says. "Zimmer wasn't the sharpest nail in the toolbox. He was growing into the job, but we knew he (Doyle) wasn't going to bunt with two strikes. And he never bunted in his life.

"Roberts knew he shouldn't have been playing in. He took a couple of steps back, but Zimmer waved him in again. If Roberts were back in his regular position, it would have been an easy play. I wasn't happy. Everything was working.''

After the game, Zimmer knew that he'd made a mistake so came up to Arlin and handed him a razor blade, and "told me to go ahead and use it on him.''

Arlin, who had thrown two one-hitters and two two-hitters already that year, never came that close again.

Neither has any other San Diego pitcher. Despite boasting Cy Young-winning starters like Randy Jones (1976), Gaylord Perry (1978) and Jake Peavy (2007) and other All-Star pitchers like Kevin Brown and Chris Young, the Padres are the only team in baseball without a no-hitter. Until June 1, they had shared that distinction with the Mets, but Johan Santana's no-hitter that night against the Cardinals left San Diego as the only team with no no-nos.

"It's crazy that we don't have a no-hitter,'' says Jones. "We've had great pitchers and a lot of stories of near no-hitters.''

Nineteen times a Padres pitcher has carried a no-hitter into the eighth inning and three men -- Arlin, Young and Andy Ashby -- have taken one to the ninth.

The most recent close call came last July 9 when Aaron Harang and four relievers kept the Dodgers hitless for 8 2/3 innings in a scoreless tie before a Juan Uribe double and a Dioner Navarro single gave Los Angeles a 1-0 win.

Like Arlin, Clay Kirby blamed his manager for losing his no-hit bid. On July 21, 1970, Kirby was lifted for a pinch-hitter by manager Preston Gomez after throwing eight hitless innings against the Mets. Kirby, who died of a heart attack in 1991 at age 43, gave up a run without a hit in the first inning and threw seven more no-hit innings.

In the bottom of the eighth, with the Padres behind 1-0, Gomez sent up Cito Gaston, who later became a manager for the Blue Jays, to pinch-hit for Kirby. The 10,373 home fans booed the move, especially when Gaston struck out and reliever Jack Baldschun allowed a single to the Mets' Buddy Harrelson in the ninth.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 1990, Kirby said he didn't understand Gomez's decision.

"When I try to look back at the logic behind it, I don't see it,'' Kirby said. "We were 20 or 30 games behind and we needed something to drum up interest in the ball club. A no-hitter would have given the franchise a bigger boost than one more victory.''

In the same story, Gomez, who died in 2009 at age 85, said that he was playing to win: "Sure you want to see somebody get a no-hitter, but in this particular game, we were behind 1-0.''

The manager isn't always at fault, of course. Sometimes the main culprit is a great hitter. In 1971, Kirby lost his second consecutive no-hit bid in the eighth inning thanks to a home run by future Hall of Famer Willie McCovey. And in 1997, the Braves' Kenny Lofton, an All-Star that year who hit .333, led off the ninth inning with a single against Andy Ashby for Atlanta's first hit of the game.

The image of Lofton's hit falling just in front of rightfielder Tony Gwynn will stay with Ashby forever. "I remember thinking, 'Oh man.' If the ball had just hung a little longer, or if it had gone a couple of feet more, Tony would have caught it. It was weak enough that he couldn't.''

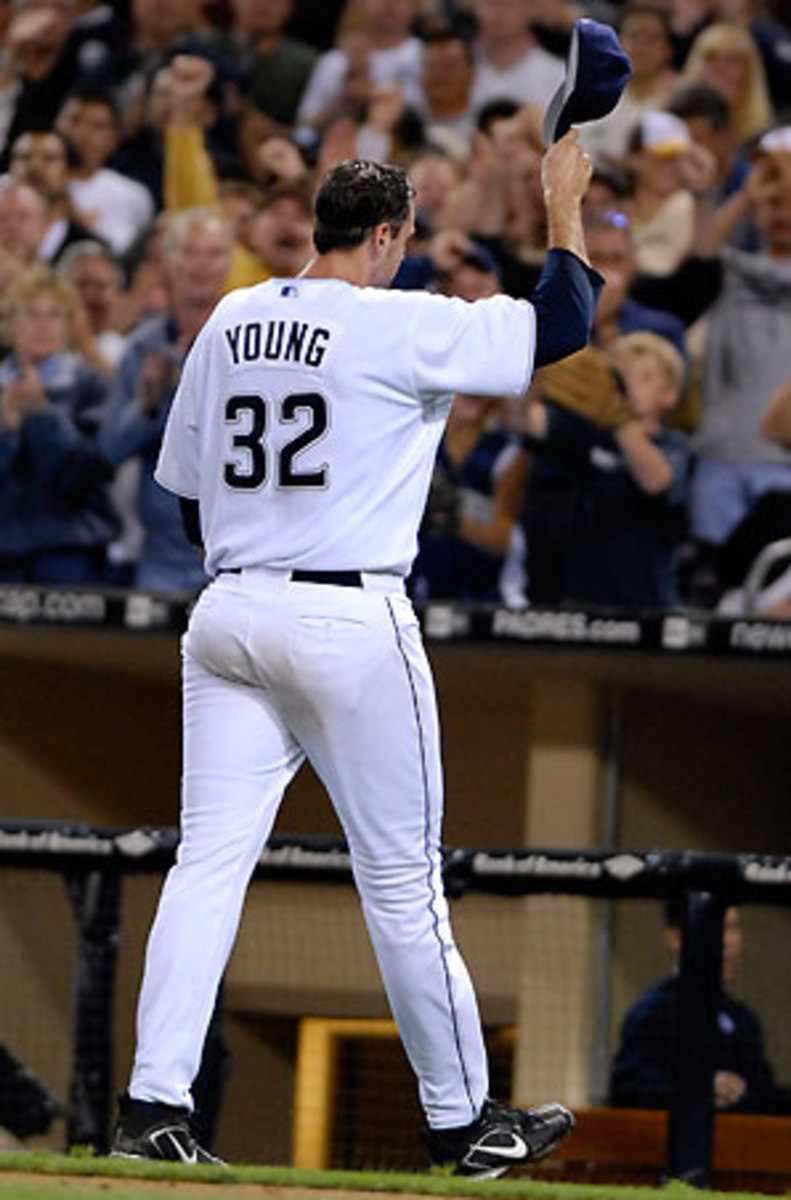

Sometimes one bad pitch is to blame. Young came within two outs of a no-hitter on Sept. 22, 2006 before surrendering a home run to the Pirates' Joe Randa -- the last of his career -- in a 6-2 San Diego win.

Bad luck played a role in Jones missing his own shot at history. On May19, 1975, he pitched a one-hitter in a 1-0 10-inning win over the Cardinals where the lone hit came on a ball Jones couldn't field.

"I couldn't really argue about the (official scorer's) call, but I was mad at myself for not fielding the ball,'' says Jones, who know does post-game radio shows for the Padres.

Less than two months later, on July 3, 1975 against Cincinnati, Jones had a perfect game until the eighth inning when "Hector Torres picked up a ground ball and threw it eight rows into the seats. And, I thought, 'there goes the perfect game.''' Two batters later, Reds backup catcher Bill Plummer hit a flair for a double down the rightfield line to break up the no-hitter.

"It couldn't have been Joe Morgan, Johnny Bench or Pete Rose that broke up the no-hitter,'' Jones says. "No, it had to be the backup catcher. When I see Bill, I say, 'You're killing me. I can't believe you did that to me.'''

There is one other obvious reason why the Padres have given up at least one hit in every game they've played: "No-hitters are not easy to get," says manager Bud Black, himself a former pitcher. "In every no-hitter, you need a pitcher with talent and multiple pitches. You need to get two or three better-than-average plays and one or two great plays.''

Black doesn't worry that his staff thinks about the no no-nos: "There's so much changing of personnel these days. The modern-day players might not all be up to speed on the history of the team.''

The fans, however, do remember. So do the pitchers. Arlin, who retired after pitching for Cleveland in 1974 and went on to become a root-canal specialist in San Diego, is often asked about his near no-hitter.

"I had a lot of low-hit games,'' Arlin says. "But I didn't get the one I wanted. I was so close. I should have had it.''