Drafted at 13, how one player changed international signing rules

On a rainy March afternoon, Jimy Kelly squeezes into his seat between the tightly packed tables at La Nueva Espana Restaurant in New York City's Washington Heights neighborhood. The smell of fried chicken hangs in the air. Kelly, like most of Dominicans who frequent the hole-in-the-wall in the working-class barrio, doesn't bother to look at the menu before ordering his usual plate of chicken and rice.

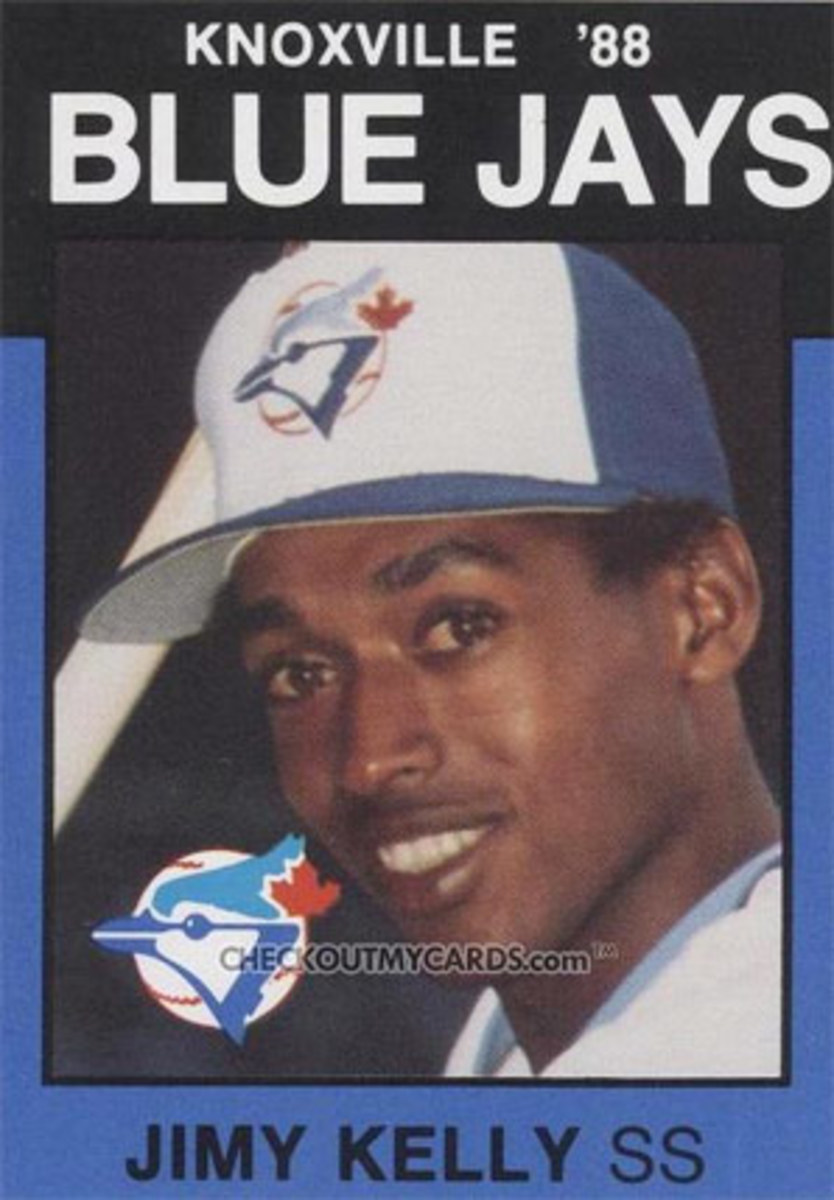

The 41-year-old takes off a gray blazer, revealing the broad shoulders and tapered waistline of a former pro baseball player. From the interior breast pocket of the jacket, Kelly removes his Dominican passport and a pair of laminated baseball cards. The passport photo was taken in 1984 when Kelly was just 13 years old and at the behest of the Toronto Blue Jays. One of the baseball cards is from 1989 Class A Dunedin and shows Kelly in the batter's box. The other, from a year later, shows Kelly fielding a grounder as a member of the New York Mets Class A affiliate in St. Lucie, Fla. In each image, he looks impossibly young -- too young to be a professional baseball player -- with dental floss arms and a body so slight it is unclear if the boy in the picture is swinging the bat or if the bat is swinging him.

"I only played baseball because I love it," he says in Spanish. "I always dreamed of being the best player but what would happen to me would be a complete surprise."

Jimy Kelly's name doesn't appear in any regular season MLB box scores. His listing on baseball-reference.com misspells his first name. He never advanced beyond Double A nor hit above .250 in six minor league seasons. But he is a living piece of baseball history. On February 15, 1984, the Toronto Blue Jays -- realizing MLB had almost no rules governing the signing of international players -- signed the 13-year-old Kelly to a contract and paid him a $5,000 signing bonus. He was the youngest prospect ever signed to a contract by a major league franchise.

Kelly's signing created uproar. Opposing teams concerned about the prospects of child labor and worried they would soon be forced to scout 9-year-old Dominicans, lobbied for new rules governing the singing of international talent. Ten months after Kelly signed, Major League Baseball mandated international amateur free agents be at least 17 years old by the end of their first professional season. The new regulation appeared in baseball's rule book under Rule 3(a), but in the Latin American baseball community it was known as The Jimy Kelly Rule. The rules evolved to include a mandate that players could not before signed before July 2 of each, creating an International Signing Day, so to speak, with some teams known to hide players weeks in advance in order to sign them at 12:01 a.m. on that day.

Thirty years after its adoption, Kelly is once again a topic of discussion -- albeit indirectly among baseball's power brokers. The Jimy Kelly Rule figures to be a centerpiece of discussions of the sport's newly formed international baseball committee, a group mandated by the 2011 Collective Bargaining Agreement to rework the manner in which teams sign international prospects. Some in international baseball argue that prospects should be at least 18 years old on the day they are signed. They argue that further postponing a prospect's entry into the professional ranks would benefit the player as well as stem the age fraud rampant in international signings, highlighted by recent cases involving Cleveland Indians pitcher Roberto Hernandez and Florida Marlins pitcher Juan Carlos Oviedo, both of whom used fake identities to appear younger and more attractive to teams when they sought contracts. An MLB spokesman declined to comment on the international age rule because he said the committee had just begun discussions.

While baseball executives weigh the future of the age rule, Kelly offers a cautionary tale. "I don't blame anyone for what happened to me," he says. "[But] I do wonder though what my life would be like if they waited just a few more years to sign me."

*****

On a mild winter morning in 1984, Kelly tagged along with his father to watch his 15-year-old brother, Julio, tryout for Blue Jays scout Epy Guerrero at the team's Dominican academy. Guerrero, who would later be described by his boss, Hall of Fame general manager Pat Gillick, as having a "knack for noticing the special player who maybe didn't have the polish, the people who maybe were a little crude," spotted Jimy behind the backstop.

"Have the younger one take a few grounders," Guerrero said.

Kelly, a star shortstop of his neighborhood team, ran onto the field. The kid --� his limbs flailing like silly string -- fielded grounders with astonishing grace. "Field another one," Guerrero commanded. And another. And another. Before the boy knew what was happening, Guerrero had ordered him to home plate for batting practice. After a successful stint in the batting cage, Guerrero turned to one of his staff members and said: "Get this kid a plate of food." Dominican for the kid's got potential.

After signing Kelly in February 1984, the Blue Jays stashed him away in their Dominican academy so he would go unnoticed by other teams. "They didn't want me to tell anyone that I had signed," he says. Gord Ash, then a Blue Jays assistant manager says, "Remember the context. There were no regulations. This was a long time ago. It wasn't a matter of when he signed but who signed him." By September, the Blue Jays sent him to the team's training facility in Dunedin, where equipment managers struggled to find uniform pants with a waistband small enough to fit the team's newest shortstop. To help Jimy acclimate, the Jays assigned Jimy's father, Juan, a locker next to his for the first few months.

After scuffling through winter workouts in Florida in the fall of '84, the following spring the Blue Jays sent a 14-year-old Kelly to the Gulf Coast League for his first official pro season. Juan didn't get a locker this time, leaving Kelly on his own, and all but two of his 27 teammates were at least 18. He posted expectedly bad offensive numbers that first season, hitting .193 with a .344 OBP but showed flashes of defensive brilliance, leading the league with 27 double plays in 48 games.

He also led his team in another category: phone bills. He racked up $1,200 in long-distance charges in one month alone. "I missed my mom," Kelly says. He remembers struggling with unfamiliar foods and long nights of tears and loneliness at bedtime. By his second season, Kelly felt more at ease even if his numbers didn't reflect that. The Jays promoted him in 1986 to the Class A team in St. Catharines, Ontario in New York-Penn League, and despite continued struggles (a .180 batting average) Toronto remained high on him. "He's going to be one helluva player," Gillick said at the time.

Kelly continued to advance through the minor league ranks based more on potential than performance. By 1988, the Blue Jays invited a 17-year-old Kelly to major league spring training camp, where he filled in for fellow Dominican Tony Fernandez, a five-time All-Star signed by Guerrero two months shy of his 17th birthday.

But by the middle of the 1988 season, Kelly started to experience the phenomena Yogi Berra once described as getting late early. Newspapers that printed articles in October 1988 hailing him as "a natural" at 17 ran headlines six months later asking, "Did Blue Jays Err in Signing Youth"? Writers warned he was washed up at 18 despite being the second-youngest member of his Class A team in the Florida State League. He stopped running out ground balls, ignored instructions, and, by his own admission, became an all-around travieso. A brat. "Now I see I didn't know how to be a professional," he says. "I didn't have the maturity to handle it."

That immaturity metastasized in the spring of 1989 when Kelly complained to Guerrero that he felt mistreated by the team. Guerrero, concerned that players he signed weren't getting a fair shot at the majors, took his concerns to the media. In a March 23, 1989, Globe and Mail article, the scout threatened to let his contract expire at season's end as a protest against Toronto's treatment of Latino players.

"Latin players have been jumping all over me since I've been [at spring training] because they feel they're not being treated fairly. And it's time for me to say something," he told the newspaper.

Guerrero suggested that the team extended more playing opportunities to American players at the expense of Dominicans. Fernandez went on record with reporters two days later echoing Guerrero's concerns. "[Guerrero] is angry because of the way [Blue Jays vice president] Bobby Mattick has been handling his players. He's too tough on them. The other [non-Dominican] guys do stuff and they don't get punished as hard as the Dominican kids do," Fernandez said. "Kids like Jimmy [sic] Kelly are being given a very hard time." The Jays initiated an investigation but five days after Guerrero griped to reporters, he told them that tensions had been resolved and that Gillick offered him a 25-year-contract.

Mediating Guerrero's own conflicts, however, proved easier than settling issues between Kelly and the team. Around the same time Guerrero aired his grievances, Kelly hit his nadir. He stood on the field during a spring workout, fielding grounders and working on double plays. The midday sun was hot and tensions high when Kelly let loose on a throw. The ball soared toward the head of 73-year-old Mattick. "It wasn't intentional," Kelly still maintains, saying he intended to throw to the instructor hitting grounders standing next to Mattick.

But Mattick ordered Kelly off the field and told him to take of his uniform. He was going back to Santo Domingo, Mattick said. Guerrero headed to the clubhouse to talk with Kelly, who was changing out of his uniform, and then to club executives to tell them what Kelly told him: It was an accident. The team relented but banished him back to Dunedin. "I thought that that moment was the end," Kelly says now. He was right. After the season, Toronto left him unprotected. The New York Mets claimed him.

Kelly played his some of his best baseball with the St. Lucie Mets (.250 average, .319 OBP) but a broken finger and injured arm hindered his progress. At season's end, the Mets cut him. A last-chance tryout with the Brewers in Phoenix ended with Kelly walking off the field after he was unable to throw. He retreated to Washington Heights, where he joined legions of other failed Dominican prospects washing dishes and driving livery cabs.

*****

At the end of his career and in the nearly three decades since, Kelly has asked an unanswerable question: Did he fail because he wasn't good enough or did he fail because he signed too young?

Only two percent of prospects signed out of the Dominican Republic make it to the majors. SI.com examined the signings of 3,099 Dominican amateurs from 2003 to 2010 and found that 18-year-old players were twice as likely to appear in the majors as 16-year-olds, and at a fraction of the price. Of the 321 16-year-olds signed, six appeared have made major league appearances. Over the same period, 27 of 914 18-year-olds debuted. Sixteen-year-old prospects earned median signing bonuses of $90,000 from 2008 to 2010 while 18 year olds collected median checks of $22,000. "You like to sign them younger to get them in your academy, start teaching them your way of playing baseball," says one scout who was not authorized by his club to speak, explaining why clubs prefer the younger yet riskier 16-year-olds.

Yet the biggest reasons to reassess the wisdom of signing 16-year-olds are physiological ones. Dr. Anne Petersen, a research professor at the University of Michigan's Center for Human Development and a member of the Society for Research in Childhood Development, says there is often a gap between a player's physical and cognitive development.

"One of the problems is that kids can look like adults but not be there at all," Peterson says. "Kids at this age still need parents or mature adults helping protect them and taking responsibility for them and unfortunately we can't count on team owners, team managers and sometimes even parents and family to protect kids from all the pressures they're going to encounter. The average 16-year-old is not ready for what a young major league ballplayer would encounter. I would advocate for raising the age."

Though the bulk of prospects have dropped out of school before training fulltime as baseball players, education advocates argue that raising the signing age would mean prospects would no longer have to chose between completing their educations and competing for baseball contracts. The Cleveland Indians and New York Mets, finding that players with high school educations were better able to deal with issues young players face on and off the field, pioneered high school programs for their prospects.

None of those options existed in the Jimy Kelly era. He knew "only baseball," he says, which explains why he ended up homeless in 2003, sleeping in a friend's black Lincoln Town Car. After baseball, he sold used cars and clothes. He served food on silver platters as a banquet attendant and drove a food truck. He has held more jobs than he can remember. He now works as a driver for a Bronx attorney, ferrying injured construction workers to doctors' appointments and court dates. It's stable work, finally.

"It's taken me 10 years to get my life in order," says Kelly.

He still watches baseball games on television, but stopped going to professional games many years ago, as it was too painful for him to be in the presence of his failed dream.

In 2001, he noticed the Bronx Community College baseball team practicing at a local park. Jose Chapman, the team's shortstop, was working on bare-handing slow rollers when Kelly walked on to the field and said, "Give me your glove." He staged an impromptu clinic, teaching Chapman and his teammates the intricacies of throwing to first while running full tilt. He then noticed Chapman's footwork, and suggested Chapman was better suited for the outfield.

The circle of players that had formed around Kelly kept asking, "Who the heck are you? Were you pro or something?" He just said he had played a lot of baseball and then handed the glove back and left.

After that day, Kelly began pondering a return to the game, as a coach. "The only thing missing in my life is baseball. I'd like a job as a scout or an instructor or something. I feel like I have a lot to teach young players," he says. "But I don't want to bother anyone [to ask for a job.]"

As he speaks, he fingers the two baseball cards he carries with him at all times. He looks at them often, each time wondering how different his life might have been had the little boy in those pictures been just a few years older.