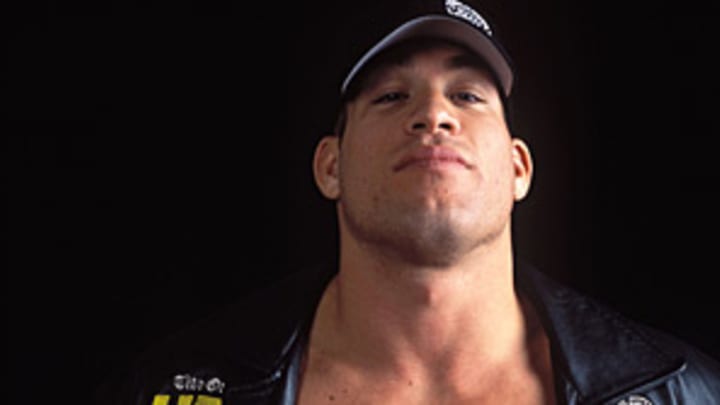

Tito Ortiz inspired for final bout of his illustrious 15-year MMA career

If you survive the drive, Big Bear eventually emerges from behind the rock. It's a picturesque four-season resort town with tackle stores and ski shops on every corner. Think log cabins, summer camp, evergreens and glistening lake, quiet and solitude. It's been a choice destination for boxers like Mike Tyson, Oscar De La Hoya, Lennox Lewis and Fernando Vargas, and Olympians who regularly use high-altitude training to boost their endurance. Lorenzo Fertitta brought Ortiz here in 2001 to show him how the pros did it, shortly after Fertitta and his brother Frank purchased the Ultimate Fighting Championship for $2 million.

"Lorenzo said if I wanted to be a champion, I had to train like a champion," says Ortiz.

Ortiz has returned many times through the years to escape the daily distractions that arise when a fighter trains close to home. Up at Big Bear, there are no calls regarding his many business ventures. There is no family drama. There is just isolation.

Ortiz's property is tucked away in a residential area with neighboring houses on either side, all of them groomed to perfection. You might drive right by without noticing the place if not for the black iron gates adorned with a permanent sign that reads "TRAINING CAMP CLOSED TO PUBLIC." Behind the gates lies a modern-day oasis: two lavish two-story log cabins are surrounded by a manicured landscape with a running brook and a walking bridge to the left and a putting green to the right. Pine trees are scattered all over the property.

In 2007, Ortiz purchased this single-acre compound that De La Hoya had built for himself from scratch. No other professional MMA fighter has made such a hefty investment in training, but Ortiz believes Big Bear is well worth it. He says the place puts him in "the fighting mood," and that is invaluable. More importantly, the place seems to feed Ortiz's confidence: if he has put in the time at Big Bear, then he knows he's as prepared as he can be.

The garage has been converted into a gym with a regulation-size cage, weightlifting equipment and a sauna. Ortiz bought the place, contents and all, so there are reminders of De La Hoya all around. In the trainers' house, an eight-foot-wide, hand-carved Mayan calendar is mounted on one of the slanted ceiling panels that look down on the living room. A wooden bench etched with the boxer's name sits outside the main entrance, which is accented with impeccable cobblestone work. The other residence, where Ortiz stays, is decorated with golf paraphernalia and has a video game arcade, a plush pool table, and an empty 10-by-8 display aquarium with a treasure chest inside. De La Hoya spared no expense.

"It's all the things I wanted as a kid," says Ortiz. "I saw it and thought it would be comfortable."

If Willy Wonka had been a fighter, he'd have created something like this place. And it's here at this combat sports wonderland that Ortiz comes bouncing out of the trainers' house at 1 p.m. to welcome his guests, his eyes still bleary with sleep. The 37-year-old fighter doesn't wake any earlier than 11:30 a.m. to start his day. Until then, the compound and its many residents stay as quiet as church mice.

Ortiz is five weeks into his nine-week camp and he's chipper. He underwent arthroscopic knee surgery a month earlier and is grateful that the joint is still holding up. "Lorenzo and Dana [White] would kill me if I dropped out [of the fight]," he says, before ducking back into one of the houses.

Freddy, Ortiz's easygoing right-hand man, instantly appears to pick up the ball. Freddy handles the details, from the comings and goings of the visitors, trainers and friends of friends who pop in and out during Ortiz's daily schedule. Freddy has been friends with Ortiz for more than a decade and assisted in many of his fight camps.

Freddy conducts the tour of the houses, which are littered with additional beds in every possible corner. The compound can accommodate at least a dozen people, but this camp, the very last of Ortiz's career, is decidedly more intimate, with only a handful of his trusted circle of friends on hand. This is the last hurrah.

Ortiz comes flying through the door with the boyish bounce in his step that he's known for. Natural sunlight beams into the spacious living room and he has a smile to match. Ortiz has never met a microphone or TV camera he didn't like and he made it a habit to do as many interviews as he can throughout his career.

"Part of the job," he chirps.

Ortiz is in a generous mood today. He's excited to go down memory lane and pay respect to the figures who've nudged his career forward along the way. The first is David "Tank" Abbott, the abrasive barroom brawler who emerged as an unlikely star circa UFC 6 in 1995. Ortiz met Abbott through their mutual wrestling coach, Paul Herrera, and became Abbott's wrestling partner. Abbott got the 22-year-old Ortiz his first fight at UFC 13 in 1997. But Abbott's greatest gift to Ortiz was opening the young fighter's eyes to possibilities. The cruder Abbott acted in and out of the Octagon, the more fans seemed to love him.

"I saw the opportunity [Abbott] had in the UFC when it first began," said Ortiz, "but Tank only thought about the fight game. I thought of it as a business. What would I do when I was 40 years old?"

These aren't the typical thoughts of a 22-year-old, but as a child of absentee parents who were both gripped by drug addiction, Ortiz's mind was programmed early for a life of self-reliance. With little guidance, he got into fights often and spent some time in a street gang while growing up in Orange County, Calif. "I was a bad kid coming up," he said. "I said what I said and didn't care. I just wore my heart on my sleeve."

Ortiz's role models came from television: pro-wrestling icon Hulk Hogan and boxing legend Muhammad Ali were among his idols. "I was a big fan of Ali and how he'd smack-talk fighters," he says. "I studied his interviews and how he'd get into [his opponent's] heads."

After his first UFC wins (he fought twice at UFC 13), Ortiz quickly crafted his cage persona -- a heightened version of the big-mouthed hoodlum of his youth. The "Huntington Beach Bad Boy" was brash and impulsive, employing a lot of theatrical devices never seen before in the struggling sport.

His first victory T-shirt featured a crude remark and he coupled that with his own version of an end-zone dance -- a pantomime of digging the grave of his fallen opponent and burying him there in the Octagon before flashing guns from his imaginary holsters. The fans went bananas for it.

"A porn company paid me $5,000 to put the T-shirt on after my fight. I was only making a quarter of that to fight," said Ortiz. "The T-shirts were kind of by accident at first, but I realized I was onto something."

Ortiz wore his "Gay Mezger is my [b----]" shirt after he beat the seasoned Lion's Den fighter in their UFC 19 rematch, infuriating the team's patriarch, Ken Shamrock. One of the sport's enduring early images is of Shamrock hanging over the cage's lip, wagging his finger in the newcomer's face and demanding that he show a little respect. Ortiz welcomed the confrontation so much that referee "Big" John McCarthy picked the fighter up like an over-adventurous toddler and carried him back to his corner to defuse the showdown. (Ortiz-Shamrock would become the first great rivalry of the Zuffa UFC era.)

Like Abbott, Ortiz resonated with the bloodthirsty 20-year-olds who had come to watch a beatdown. However, the similarities between Abbott and Ortiz stopped there. Outside the Octagon, Abbott didn't like to train, but Ortiz knew it was a necessity.

After his 1999 defeat by UFC middleweight champion Frank Shamrock at UFC 25, Ortiz went back to his day job as a clerk at Spanky's Adult Novelty Store, but owner Ron Haskins wouldn't let him stay for long. Haskins told Ortiz that if he'd nearly beaten a fighter with years more experience, so he owed it to himself to give the sport all he had. Haskins became Ortiz's benefactor, agreeing to cover his rent, food and cell phone expenses if he'd train full time.

Ortiz immediately traveled to Frank Shamrock's gym in San Jose and trained with him for a month straight. Shamrock showed Ortiz that there was a science to fighting. Ortiz had never seen a heart rate monitor before Shamrock strapped one to his body. Ortiz learned how to read (and eventually control) his own body. His recovery time and endurance improved drastically. Six months later, Ortiz -- now training in multiple disciplines -- became a UFC champion.

"I owe it to Frank. He's the first guy to understood all-around what this sport was," he says. "Wrestling, boxing, jiu-jitsu and kickboxing; he understood all of them and when he left [Shamrock relinquished his title after UFC 25 and retired from the sport], I followed in his footsteps."

By 2000, the UFC was dying, but Ortiz had become the most popular fighter in the world. He poured himself equally into training and self-promotion. Disenchanted by the lack of sponsorship opportunities available to fighters at the time, he launched his Punishment Athletics clothing line and began to sell T-shirts himself in hotel lobbies at events. He printed his own trading cards and walked the arena row by row, placing one on every seat.

"When the fans aren't there, it's no longer a sport," says Ortiz. "The T-shirts, the Gravedigger, the flamed shorts, the beanies: it was marketing from the beginning. It was, what can I do so I'm not forgotten?"

Ortiz's efforts caught more than just the fans' attention. In early 2000, Dana White, a Las Vegas boxing gym owner with friends in high places, approached Ortiz to manage him. Ortiz says it was White who hung up on UFC owner Bob Meyrowitz when he wouldn't agree to the new manager's demands. (Meyrowitz conceded the next day, according to Ortiz.)

Within a year, Meyrowitz would sell the UFC to the Fertitta brothers, who had been tipped off about the promotion's dire straits by White, an old high school friend. White became president and a minority owner of Zuffa LLC, the company created to run UFC events and turn the floundering brand around.

Ortiz was passed to a lawyer who had close ties with White and wouldn't push the promotion for concessions like first-class airfare or extra tickets to shows. But when Ortiz's contract renewal came up in 2003, he'd shed his representation and wanted to negotiate a new deal himself. At this point, Fertitta probably regretted taking Ortiz to Big Bear in the first place.

"I looked at boxing and saw that 75 percent of the revenue went to boxers and only six percent went to [MMA] fighters," says Ortiz. "What was I doing differently from boxers? I decided to stand my ground."

Ortiz sat out the next 10 months, as both sides rehashed his contract. He said Fertitta and White verbally promised him bigger purses and other incentives down the road, but Ortiz wanted everything in writing.

"Lorenzo and Dana were pissed that I didn't have trust in them, but I was kid who'd never had trust," says Ortiz. "I didn't know who to trust; my whole life had been like that. I wasn't going to do something on someone's word. I can't tell you how many times my dad said he would be there for me and never was."

Ortiz eventually became one of the first fighters (if not the first) to receive a sliver of the promotion's pay-per-view revenues when he fought -- but it came at a price. As Ortiz and other fighters who challenged the promotion's business model would learn, in Zuffa's eyes, you were either with them or against them. There was no in-between.

In subsequent renegotiation periods in 2005 and 2008, Ortiz leveraged his popularity into other opportunities outside the sport. He did a guest referee stint for TNA pro wrestling in 2005 and in 2008 appeared on The Celebrity Apprentice. Ortiz also played rival promotions -- all looking to snatch him away -- against one another to remind Zuffa that he was still a bona fide commodity.

"[It was] all negotiations. I was never going anywhere," says Ortiz, who was fueled by his desire to make a better life for his children than the one he'd had. "I was just showing the UFC that I was worth the money they'd be paying me."

During this time, White's festering disdain for Ortiz spilled into the public. Both sides had their unflattering moments. In 2007, White was behind a bizarre Spike TV special that documented an exhibition boxing match the two had allegedly agreed upon but never happened. The show painted Ortiz as a coward when White claimed the fighter no-showed at the weigh-ins. What the special didn't show was Ortiz's side and his insistence that White knew ahead of time that Ortiz wouldn't commit to the bout because the financials hadn't been squared away in time. In May 2008, Ortiz retaliated with a "Dana is my b---h" T-shirt he wore to the UFC 84 weigh-ins.

"We're both alpha males and you can't have two of them in one room," says Ortiz.

Discussing White brings on a mix of emotions for the fighter. Ortiz seems genuinely hurt by White's past and present actions, but he's also remorseful for his own behavior at times.

"Dana was a great friend of mine," said Ortiz. "I loved him. I still love him. He hates me, but I love him. He did a lot for me. I remember the day he came to my apartment and said, 'Tito, give me one chance and I'll make you a millionaire.'"

On Friday, Zuffa will induct Ortiz into the UFC Hall of Fame as its eighth member, though it seems unlikely that the fighter will receive any more recognition from the promotion than that. However, there's still a strong army of fans who will always accept him for who he is and what he's done in the sport.

"I was always dying for the attention, for the love, and MMA is what gave it to me," he says. "The fans gave that to me."

And with the conclusion of the interview, a teary-eyed Ortiz rises from his seat and disappears out the door.

With his media commitments nearly finished for the day, Ortiz is spread out on the couch in the main house, watching a UFC event on Fox Deportes. The bouts aren't captivating, but they don't have to be to keep a fighter's attention.

Freddy is in the kitchen marinating mountains of raw meat in disposable tin pans for dinner. The counters are packed with cases of energy drinks, tubs of powders and a variety of other nutritional supplements.

Ortiz's support team convenes here to discuss the night's details. Jason Parillo, a retired pro boxer who's coached Ortiz for his last few fights, is sitting at a side table. Ortiz usually does his cardio training when he wakes, attacking one of the local mountain terrains on his bike, but since the media took up that time today, the missed cardio will have to be made up elsewhere.

Aaron Rosa, an introverted heavyweight who Ortiz flew in from Texas, is out on the back deck at a picnic table with a few others. Paul Lacanilao, Ortiz's strength and conditioning coach for the last decade, is standing close by. They're all waiting for Ortiz's cue to convene at the garage for the night training session. During his entire career, Ortiz has trained so he peaks around 8 p.m. -- roughly the same time he steps into the cage for his fights.

Ortiz finally emerges from the house, slamming the kitchen's screen door behind him. First up will be sparring with Parillo. For a few minutes, Ortiz hits the mitts for the benefit of the cameras before the crew is politely asked to come back later. Most fighters don't want their striking practices recorded and posted online for their opponents to study and digest. Ortiz, a wrestler who never fully adapted to the striking game, is at his most vulnerable now. The strangers are politely ushered outside as the garage doors roll down, the pulsating bass of the music blaring inside floats off into the night.

Meanwhile, the group in the main house's living room is joined by Jenna Jameson, who has driven up from Los Angeles with a friend to spend the weekend. Ortiz and Jameson have been together for six years and have 3-year-old twin boys, Jesse and Jette. Jameson is probably the most recognizable (former) porn star in the world, and like Ortiz, she has leveraged her niche celebrity into mainstream success.

Jameson's battles with drug dependency aren't a secret, and she and Ortiz have had some rocky moments because of it. But there's no doubting that they are in love. When Ortiz comes into the house for a few minutes respite between sessions, he collapses onto the couch next to her, resting his head in her lap.

Kenny, a 5-foot-5 Asian with a full-shirt tattoo and a Fu Manchu down to his chest that makes him a Central Casting favorite, has the group's attention as he enthusiastically describes his stint on HBO's True Blood as a featured vampire. The mood in the room is light, which is just the way a fighter likes it before he heads into battle. Part of the reason why Ortiz surrounds himself with these men is because they put him at ease. He can be himself in front of them without fear of judgment, and that allows him to concentrate on more pressing matters.

By 10:30 p.m., Ortiz and his team are back in the garage. Ortiz is sitting on the stairs next to the cage, trying to give his body a little extra rest before he starts a hellish strength and conditioning regimen.

"I do get tired of this," he admits. "The fighting's the fun part. This isn't."

Sensing his weariness, Lacanilao summons Ortiz to the first apparatus and begins leading him through a grueling chain of exercises, one after the other, involving weights and pulleys. Ortiz is still in phenomenal shape for a 37-year-old and can push his body far past what it should be able to do at his age. Throughout his career, he has had five major surgeries, including risky back and neck fusion operations from which other athletes might not have come back. Ortiz did, but the wear and tear on him remains.

The session moves outside into the driveway. Paul instructs Ortiz to grab a rope wrapped around the trunk of the biggest tree on the property and begin shrugging with all his might for one minute. Then Ortiz must pick up a 40-pound medicine ball and throw it over his back across the asphalt, run to the other end to pick it up, and then throw it over his shoulder again.

It's pitch black outside now and bats are flying around Ortiz's head as he races back and forth between the tree and the driveway with Lacanilao in tow. The guys watch from the sidelines, some lending words of encouragement as Ortiz grunts, moans, then screams out in pain. He is exhausted, but he doesn't quit until Lacanilao is satisfied.

At the grill, turning over pounds of chicken, beef and asparagus, Ortiz is tired, but content. He didn't train at Big Bear for his last two fights and, he says, he wasn't prepared, which greatly shook his confidence. Being back here on the hallowed grounds where boxing greats have also sweat and bled gives him inspiration.

It's 1 a.m. when everyone finally sits down at the dining room table to eat. Even Jameson joins the feast for a few bites. The room is alive with conversation and camaraderie. This isn't a team, it's a family. Everyone knows they're a part of something special and this is one of the last times they will get to share moments like this.

After the meal, Ortiz wishes everyone a good night. He and Jameson slip out the door and head back to the other house. Tomorrow he will start all over again and five weeks after this writer's visit to his camp, he'll say goodbye to this way of life forever. But on this night, he's surrounded by people who love and support him unconditionally, and that makes him a very happy man.