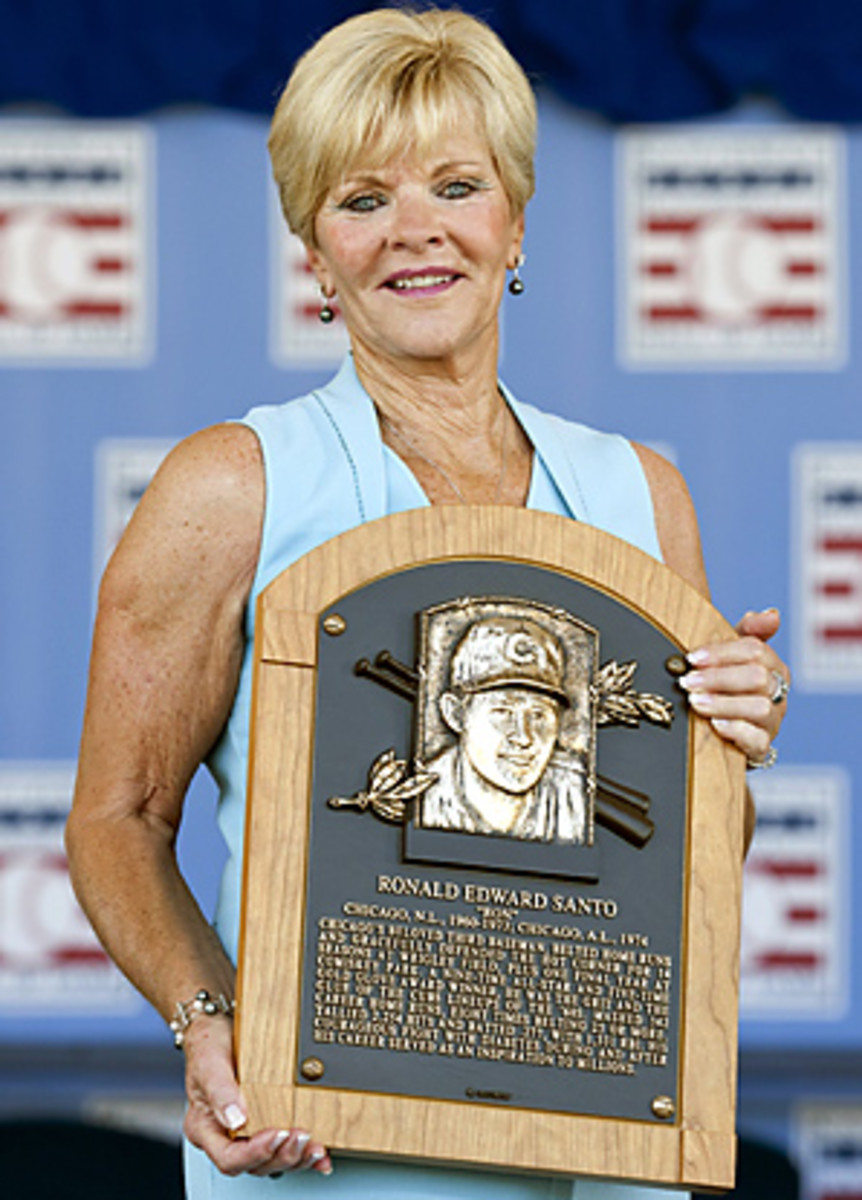

Vicki Santo hits it out of the park at late husband's induction ceremony

COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. -- Ron Santo was standing in the on-deck circle, his blood sugar having dipped too low to fully concentrate. Santo, the great third baseman who had Type 1 diabetes, was weak and his vision was blurry. His teammate, Billy Williams, was batting with two men on. Santo was hoping he'd strike out, so he could get back to the dugout sooner.

Instead, Williams worked a walk, and Santo's new plan was to swing at the first pitch to end his at bat as soon as possible.

"He didn't count on seeing three balls coming to him," recalled his widow, Vicki Santo, "so he picked the middle of the three and swung hard.

"He did it, a grand slam."

Santo battled diabetes ever since he was diagnosed at 18 years old, and the incident relayed by his widow may have been the most extreme single instance in which he overcame his illness on the field. He didn't call for a pinch hitter then but received one Sunday -- and she, too, hit a grand slam.

Santo's 15-year big league career, during which he was named an All-Star nine times and won a Gold Glove five times, was christened as that of a Hall of Famer in Sunday's induction ceremony in Cooperstown. The honor, however, was posthumous for Santo, who died in Dec. 2010 of bladder cancer, making for a bittersweet occasion.

After all, Ron Santo himself had once told Chicago Magazine in 2002, "The last thing I want is to die and then be put into the Hall of Fame. It's not because I won't be there to enjoy it, exactly. It's because I want to enjoy it with family and friends and fans. I want to see them enjoy it."

One of his sons, Jeff, admitted in a news conference on Saturday that after previous elections failed to earn his father's induction -- more than three decades passed from his initial eligibility on the 1980 writers' ballot to his eventual selection by the Hall's Golden Era Committee in 2011 -- that they weren't always certain what they'd do should the honor come too late for Ron to enjoy it.

"We would talk as a family," Jeff said, "if he gets in and he's not here, we are not going."

Yet, in a stirring speech of grace and eloquence on Sunday, Vicki Santo urged those in attendance -- vocal contingents of both Reds fans for Barry Larkin and Cubs fans for Santo -- to dwell on the positive of her late husband's career and life.

"This is not a sad day, not at all," Vicki said. "This is a very happy day. This is an incredible day for an incredible man, a man who lived an extraordinary life to its fullest.

"... He would not have stood up here today and bragged about what he has done to try to help others, so the one advantage to him not being here is, in this case, he can't tell me what to say."

Had Santo been here, Vicki surmised after the ceremony, "his speech would have been all about his career, which it should be. I couldn't talk about that. But I think that there was a message in his journey. That's what I tried to get across to the fans."

Santo was, most pertinently, a Hall of Fame ballplayer with 342 career home runs, including at least 25 in eight consecutive seasons. He was a four-time league-leader in walks and twice in on-base percentage, contributing to a career .826 OPS in a notoriously pitching-dominated era, so that his 125 OPS+ (adjusted for league and ballpark) ranks 11th all-time among third basemen with at least 1,000 games played.

Santo was also a beloved broadcaster, working Cubs games with the "enthusiasm and passion with which he played the game," said Pat Hughes, his partner in the radio booth and "with no emotional filter," according to Vicki. Indeed, the video celebration of his life included more than one instance in which Santo moaned on air in disbelief at more Cub misfortune.

(He laughed, however, at his own situation. When his hair piece got too close to a heater and caught fire in the booth, he joked how appropriate such an event would happen when the opponent's starting pitcher was named Al Leiter.)

And, though Sunday was about Santo's contributions to baseball, he was also a hardworking advocate on behalf of diabetes awareness. The disease made for a daily battle and led to the amputation of both of his legs below the knee. But Ron Santo remained positive that it could be beaten, both in fully living each day as he had on a baseball field but also that a cure could be found, which is why he invested the time and energy to help raise $65 million for the Juvenile Diabetes Research Fund, according to Vicki Santo.

"On a given day he played doctor and patient, as well as third base," Vicki said. "He tested his sugars by taking batting practice. He checked his glucose levels by fielding grounders. He gauged the amount of insulin he would need after running the bases."

"He embraced his gift and his hardship equally," she continued, "believing that one would not have mattered without the other.

Of course the weekend would have improved with Santo's presence. Of course it is a shame that a deserving player with a severe illness had to watch as he was repeatedly passed over for election. Of course more fans would have turned up in Cooperstown to hear his affable storytelling review his career. Of course the family had reason to feel bitter.

But, instead, with humility and positivity, the Santo family saw an opportunity to celebrate their father and to promote a worthy cause.

"Our dad would want us to embrace it," Jeff said. "It's his legacy and if more people, if this could shed a light on what he did for baseball and also for JDRF, that's a great thing that more people could understand his story and what kind of man and ballplayer he was."

The statistics on the back of Santo's baseball card and the words and numbers on his newly engraved Hall of Fame plaque tell the story of what kind of ballplayer he was.

The anecdotes and memories of those close to him tell the story of what kind of man he was.

"He did not complain, and he did not want sympathy," Vicki said. "He believed he'd been chosen to go through these things so that he could deliver a message of perseverance to inspire those with problems of all types."

Never was that more apparent than when a nurse was pushing Santo in a wheelchair into the operating room for his second amputation surgery.

"The timing was perfect for this operation," Vicki heard Ron tell the doctor, "because he would be back for Opening Day."

Timing was not perfect for Santo's induction, but his family made the most of what truly proved to be a wonderful day.