Liu awes with tough mentality but returns to China emptyhanded

LONDON -- Last week Yao Ming, the greatest basketball player in Chinese history, was speaking here about the coming redemption of Liu Xiang. Four years ago in Beijing, the greatest track athlete in Chinese history disappointed a cool one billion people when he pulled out of the qualifying heats of the Olympic 110-meter hurdles with an injury to his right Achilles tendon.

"He got hammered by the public," said Yao -- so much so that he felt it necessary to check on Liu that night at his room in the Athletes Village. "I just wanted to talk with him. [...] I wanted him to know that life is more than just winning games. I wanted to show that not everybody treat you that way. And after four years that's a perfect story for him: From the bottom. I will not say he has to win a medal. If he can just step out to the starting line? He's a winner."

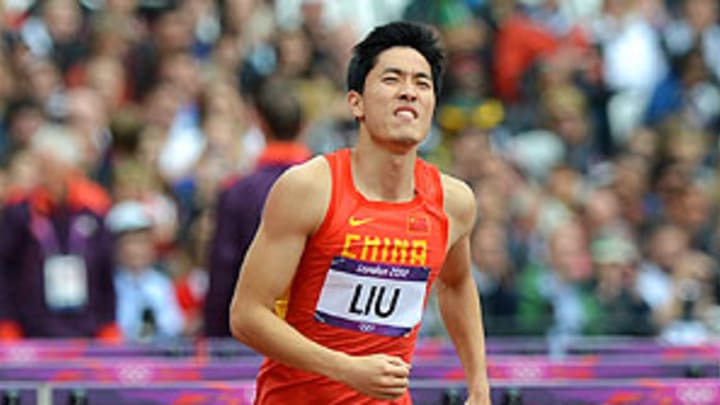

But Liu never will make it to the starting line of Wednesday's 110-meter hurdles final at the 2012 Olympic Games, and for the second straight time the face of China's rise to sporting dominance will not seal matters with the most symbolic of wins. On Tuesday, Liu crashed out of his 110m qualifying heat at Olympic Stadium after failing to clear the first hurdle, a victim of the same chronic Achilles injury that he suffered in 2008, then overcame to return to world-record form -- 12.87, wind-aided -- this past February in Eugene, Ore. China team leader Feng Shuyong said that it's possible Liu had, in fact, fully ruptured the tendon Tuesday, but couldn't confirm that pending further tests.

In any case, after 2,700 years it might just be time to change the name to "Liu's heel". "For that to happen to one of the best hurdlers of all time is just a tragedy," said U.S. hurdler Aries Merritt, who qualified for Wednesday's semi-finals in the heat previous to Liu's with the best time -- 13.07 -- of the morning. "He just hit the hurdle and he went down. I can't believe he hit it: When I saw it I was in the most absolute shock. I just have never seen him -- of all people, because he's so perfect all the time -- hit a hurdle."

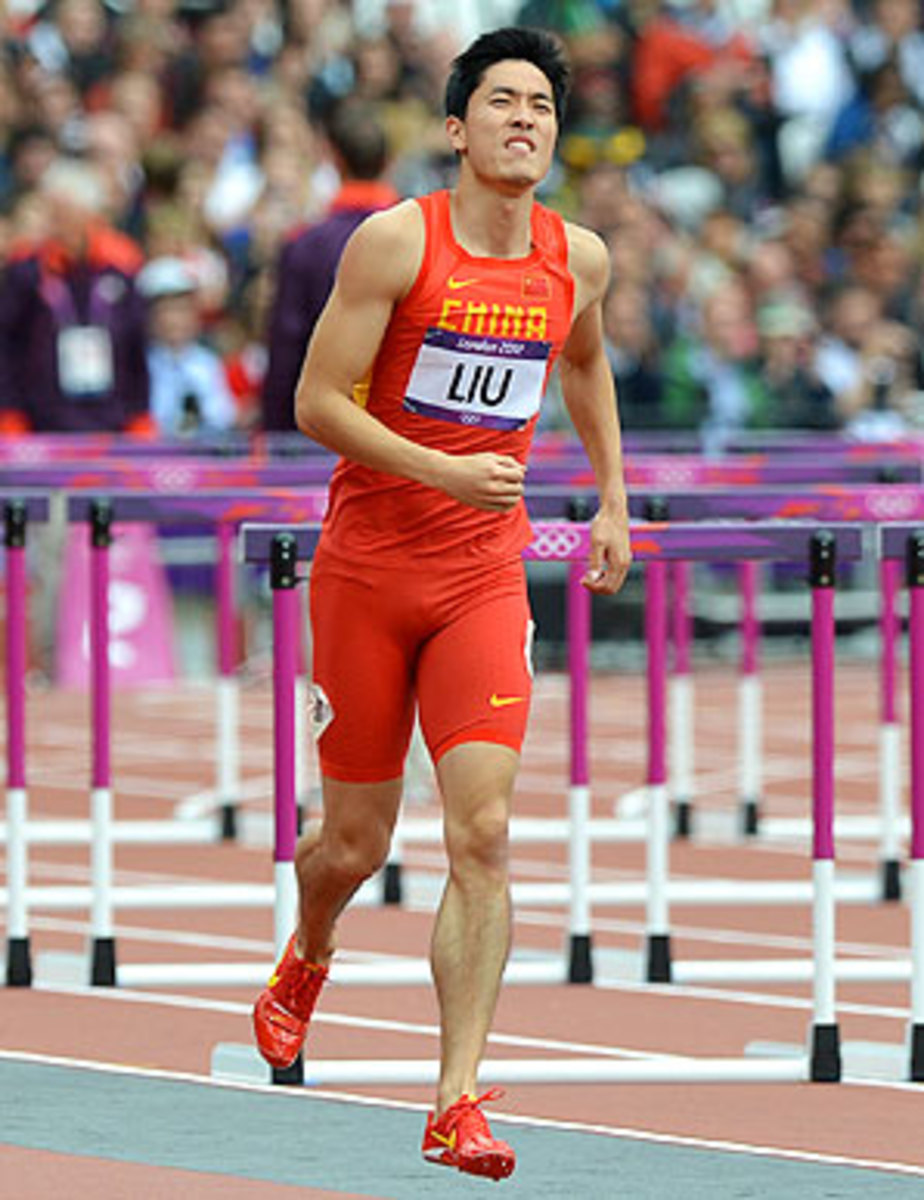

In truth, after giving an odd grin just before the gun cracked, out of the blocks Liu looked hardly perfect. Running in Lane 4 and clearly lacking lift, Liu struck the first hurdle flat with his left heel; he tumbled to the track and grabbed his right Achilles, already taped for support. After sitting for a few seconds, then banging his head once on the track, the 29-year old Liu stood and, using only his left foot, hopped off the track and into the nearest stadium tunnel.

His day, and perhaps Olympic career, looked as if it were ready to end on a miserable note. But then something remarkable happened: Liu changed his mind. Halfway down the tunnel he stopped, thought a moment and, still on one foot, turned 180-degrees back toward the track; Liu came hopping up the tunnel and back into view. With each hop, the cheering grew.

"He was still determined to go the finish line: That's true Olympic spirit," Feng said. "He showed that athletes are not just about winning, but about showing that spirit to the world."

Liu then hopped the entire length of the 110-meter race -- and some 250 meters in all -- veering into the middle to kiss the final Olympic hurdle, the one he hadn't crossed in eight years. Hungarian hurdler Balazs Baji, who had been running next to Liu in Lane 3, lifted Liu's arm as if to declare him champion.

"He just hopping all the way through: That show everybody that he wanted it to happen and he was so sorry," Baji said. "Falling in the first round is just the worst thing that ever could happen with an athlete, especially when he wants to win. I just want to say him that I'm sorry and good luck for the future. Especially that he had to quit in Beijing and now in London again."

Two other opponents -- Great Britain's Andrew Turner and Spain's Jackson Quinonez -- rushed in and draped Liu's arms over their shoulders and then carried him off the track. London's last glimpse, four minutes after he had been appeared as one of the Summer Games' biggest stars, was of a seated Liu being rolled out of the sunshine in a wheelchair.

It wasn't, of course, supposed to be this way. In 2004, the 21-year-old Liu shocked Asia as much as the rest of the world by running 12.91 to win the gold medal in Athens. He showed that the long-overlooked Chinese could compete with the West's dominant sprinters, something that was just as important for the Chinese Olympic committee.

"He was inspiration," said Merritt, who was 19 then. "He showed me that anyone can do it: Anyone."

Though not as fast as his top competition in the flats, Liu benefitted from sublime technique, seeming at his best to be oozing -- more than jumping -- over the hurdles. "A thing of beauty," said American hurdling great Renaldo Nehemiah. Liu set a world record of 12.88 in 2006, and ran a 12.95 to win the 2007 World Championships, setting the stage for a Beijing coronation. His withdrawal there was a cultural bomb: His coach, a TV anchor and millions of fans cried. Liu was forced to stop competing for the next 13-months but promised to return for these games -- and never wavered. "His patience," said Merritt, "is phenomenal."

A year ago at the world championships at Daegu, Liu's blistering start was impeded by the flailing arm of arch-rival Dayron Robles of Cuba; Robles was disqualified, and though Liu officially finished second with a time of 13.27, many observers felt he'd been robbed of the gold. It will be easy for laymen to take his withdrawal from Beijing -- or injury here -- as some kind of psychic fold, but Liu's toughness over the previous three years left his peers awed.

"I always told people, when Liu came out of China he didn't come out to lose," Nehemiah said. "You had to run a world best or almost a world record to beat him -- and that's uncanny. The closest person he reminded me of was (American 200- and 400- meter champion in 1996) Michael Johnson, who wasn't showing up to win a race. He was showing up to dominate. Liu had that competitive spirit. You had to run a flawless race to beat him.

"Americans may discredit him because he's only won one Olympic games, but we're spoiled. To accomplish what he has in the period he has, to watch his dominance when he is healthy, is to be commended and respected. The only unfortunate thing is that he hasn't been able to put together a string of championship years in succession."

The first sign of trouble for these games came earlier this month, when Liu withdrew from a Diamond League in London. It's now clear that his Achilles was a large part of the problem.

"Coming from someone -- myself -- who experienced two Achilles ruptures, it's the most emotionally and psychologically devastating injury you can have," says Nehemiah. "It's a fearful thing, and it's an excruciating pain when you have it before it does rupture. So I can only imagine that he was just hopeful it would stay together as long as it could. He was probably a bit more injured than we all knew."

But in the coldest Olympic light, that doesn't matter as much as Liu's current record: one gold and two disasters. Yao had a theory, last week, that the Chinese public grew up after Liu's withdrawal in Beijing, and that they had come to appreciate an athlete's arc and his response to adversity, as much as his hardware. "People realized, okay, sports is more than winning gold or games," Yao said. "We want see those fighting experiences, the toughness in there."

It sounded good. But Liu goes home to China now, heartbroken, admirable -- and empty-handed. One more time, the nation will shake off its shock and wipe its tears. Then man, theory and country will be put to the test.