Love him or hate him, Miller earned respect in Hall of Fame career

For old times' sake, here's how it should go when Reggie Miller is inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame on Friday night. As he walks up to the podium, he should flash a choke sign at Patrick Ewing, "accidentally" bump Michael Jordan and intentionally catch his leg on Joe Dumars' chair to make it look like he was tripped. A video of highlights of his 18-year career should be playing, with a soundtrack of Pacers fans chanting "REG-GIE, REG-GIE," intermingled with the boos and catcalls from fans of all the teams he bedeviled through the years.

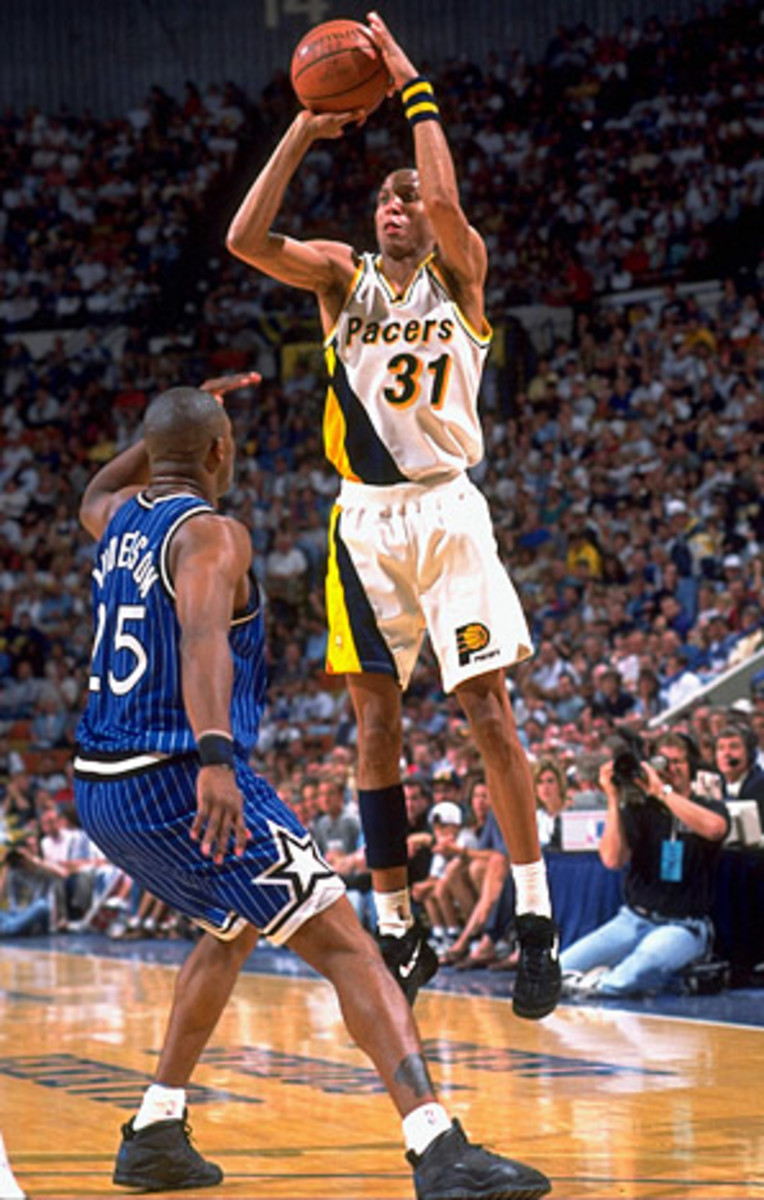

Everyone around him should be a little annoyed, a little amused and generally stirred up, because that's the atmosphere in which Miller thrived throughout his career, the one he created and used to drive him toward the Hall. He was a deadeye shooter and a cold-blooded clutch player, but as much as anything, Miller was a magnificent irritant who seemed to draw energy from his opponents' frustration. His most memorable talent may have been his ability to worm his way under the skin of everyone except the Indiana fans who made a skinny Southern California kid one of the heartland's favorite sons.

He was theatrical and showy and made no bones about playing with the proverbial chip on his shoulder (wouldn't you, if the world kept reminding you that your big sister, Cheryl, reached basketball stardom before you did?). At some point, unless you were a Pacers fan, you probably said to yourself, "I hate that guy," maybe because he had just stuck a three-point shiv in your team's heart and then bowed to the crowd, or suckered a ref into calling a foul by kicking his leg out into the defender on his jumper and tumbling to the deck. But you said it with a grudging smile because darn it, this cocky bag of bones was tougher than he looked, and shrewd and endlessly entertaining, and you couldn't help but appreciate that.

[Zach Lowe: Where does Miller rank among shooting guards?]

Even Spike Lee, whom Miller famously taunted and tormented, couldn't work up a full-on hatred. Lee always seemed to understand that it was all part of the show, even when Miller had the upper hand -- never more so than in his signature moment, the eight-points-in-8.9-seconds miracle he pulled off to steal a playoff game from Lee's beloved Knicks at Madison Square Garden in 1995. That game was the perfect companion piece to his 25-point fourth quarter in a comeback victory at New York in the 1994 playoffs, and together those performances gave Miller a national identity and put him on the Hall of Fame track. That's when we found out how much he loved to be hated. He particularly enjoyed playing in front of hostile New Yorkers, he said, "because I love how they dog me out." He never won a championship, true, but after breaking hearts on Broadway, no one could ever say that hole in his résumé was because Miller faded in the big moment. In fact, he lived for them, his confidence overflowing. "The flowers are in bloom, the trees are green, spring is upon us and the playoffs are here," he once said as another postseason approached. "That means it's Miller time."

For all his feistiness and flamboyance, Miller was a model of consistency and reliability as well. Like Bird and Magic, like Ripken and Elway and Marino, he was a star who played his entire career in one city and became so much a part of it that you couldn't imagine him in any other team's uniform. Only Utah's Karl Malone and John Stockton have played more NBA games with one team. Indiana fans, many of whom booed when the Pacers drafted him with the 11th pick in 1987, ahead of homegrown Hoosier hero Steve Alford, came to love him for helping the Pacers stick it to the boys from the big cities so often. He backed down from no one, not even Jordan, with whom he had a memorable scrap in 1993. Miller's hands-on defense antagonized His Airness so much that Jordan once said that playing against him was like "chicken-fighting with a woman."

But Miller was the one being grabbed at least as often as he did the grabbing. Remember that he put up most of his numbers -- his 320 postseason three-pointers are the most in NBA history, and he held the record for career treys at 2,560 until Ray Allen broke it in 2011 -- in the era when NBA defenders were allowed to get away with all kinds of clutching and holding and hip-checking. Miller, with his spindly 6-foot-7, 195-pound frame, was bounced around like a pinball much of the time but still managed to get off his familiar array of shots -- his quick catch-and-shoot beyond the arc, his baseline fadeaway, his climb-the-ladder floater -- that were all the result of meticulous pregame shooting drills that were almost military in their precision.

If you arrived at Market Square Arena and later Conseco Fieldhouse early enough, at least three hours before game time, you were sure to see Miller on the court in a long-sleeved shirt, going through his shooting routine with a ballboy rebounding and crisply passing to him. First free throws, then layups, then medium-range jumpers and finally three-pointers, all from a variety of angles, all with his unorthodox motion, his shooting elbow flying out in a way you'll never see in an instructional video. I once saw him hit 16 consecutive threes during one pregame, and that didn't include the several he made before I started counting.

But most fans never saw the work that Miller put in to be great. He could have toned down the theatrics a touch and been known more as the hard-working superstar than the antagonistic villain, but then he probably wouldn't be about to take his rightful place in the Hall of Fame. Besides, no one ever really bought that he was a bad guy. It's hard to think of another star with a persona quite like Miller's. Even when you were thinking, "I hate that guy," you had to admit, you loved him a little, too.