Political soothsayer Silver shares his musing on sports, stats, more

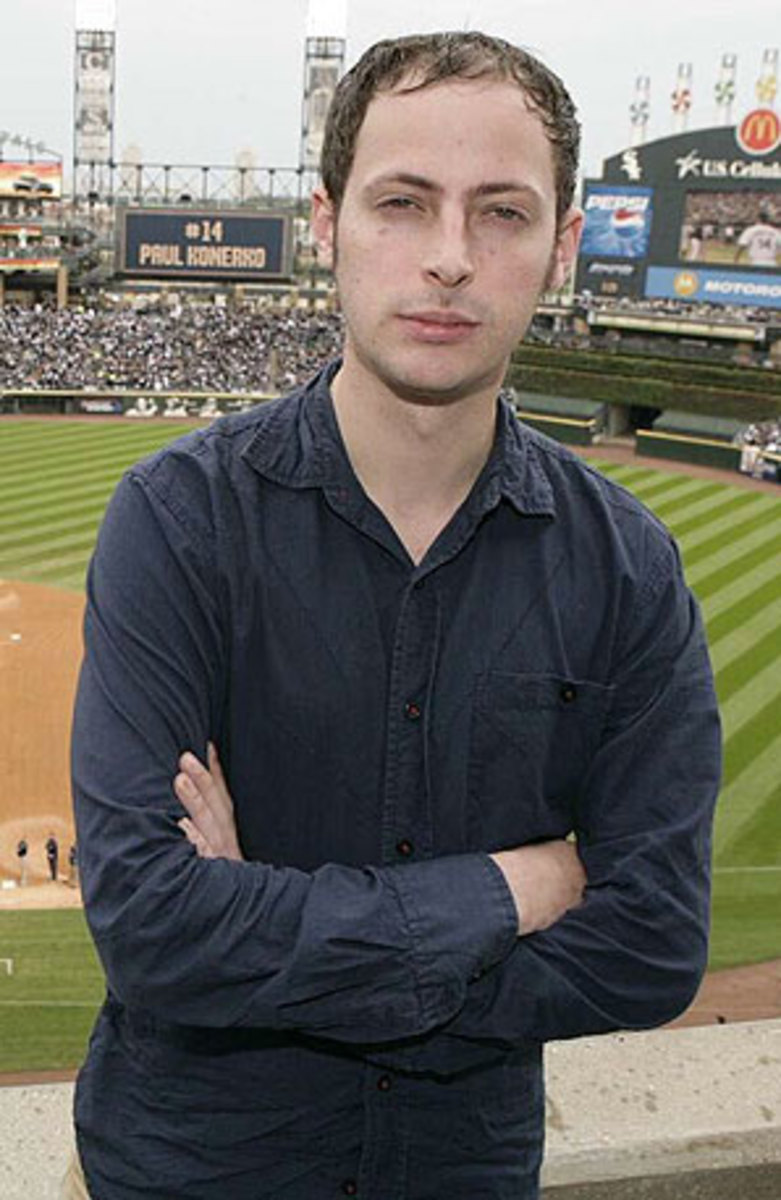

A couple of Saturdays ago, in the grace period between the GOP and Democratic conventions, political poll cruncher Nate Silver somehow found the time to fight back yawns and accept my invitation to go to a ballgame.

In the Scorecard section of this week's SI, I report on that afternoon at Yankee Stadium. And I tell the story of Silver's transformation from the guy who developed PECOTA, an uncanny forecasting model for Baseball Prospectus, to the soothsayer who correctly called 49 of 50 states in the last Presidential election and came within a percentage point of nailing the popular vote.

Having just read Silver's forthcoming book, The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail -- But Some Don't, and followed his political blog FiveThirtyEight for several years, my notebook was groaning as I rode the D train back from the Bronx. Silver may have been sucked into psephology -- the study of elections -- but he often circles back to the field where he first made his reputation. And so, with a nod to the political season and his book's publication on Sept. 27, I'm sharing an info dump of Silver on sports.

In baseball, he reports, the nerds have won; GMs, scouts and other "good baseball men" have essentially accepted the Moneyball paradigm. After years in which conventional thinking prized batting average above all, on-base percentage is now the stat most highly correlated with free-agent money.

Silver remembers when it wasn't that way. A decade ago, attending the Winter Meetings in New Orleans, he could feel the frost from scouts bellied up to the bar, warily eying the recent analytics grads from MIT and Ivy League schools across the lobby as they pressed resumes into the hands of GMs. Now front offices are no longer like high school cafeterias, and Silver believes the game is better for it.

Their détente, he explains in his book, makes perfect sense: Each has data the other lacks, but needs to deliver the best possible forecast. Silver profiles Los Angeles Dodgers scout John Sanders, a former bonus baby whose pedigree might mark him as a Moneyball skeptic. Instead, Sanders charts a middling path between the speed gun and the mainframe.

He puts less stock in the scout's traditional "five tools" (hit for power, hit for average, speed, arm strength, defensive range) and more in touchy-feely, "mental toolbox" stuff -- things like preparedness and work ethic; concentration and focus; competitiveness and self-confidence; stress management and humility; and adaptability and learning ability. These aren't things a scout can tell by gut or a number cruncher can tell by metric. But Sanders makes a sound case for them. As Silver writes, "The further you get away from the majors -- the more you are trying to predict a player's performance instead of measure it -- the less useful statistics are."

Once you focus on the big leagues, though, baseball is a stat geek's playground. Because the sport offers what Silver calls "perhaps the world's richest data set," it eventually tends to cycle through plenty of low-probability events. In 2011 the Boston Red Sox failed to make the playoffs, even though at one point during that season they had a 99.7 percent chance of doing so. Just the same, as he puts it, "I wouldn't question anyone who says the normal laws of probability don't apply when it comes to the Red Sox."

I asked Silver about one of the characters in his book, a professional bettor named Bob Voulgaris who has translated his feel for the NBA into a house in the Hollywood Hills and a condo in Vegas. Late in the 2001-02 season Voulgaris noticed that over-under bets in games involving the out-of-the-running Cleveland Cavaliers tended to go "over" -- that is, the total score of their games wound up exceeding the bookmakers' "over-under" line.

For all his resources -- he has research assistants punch information into computer models and monitors Twitter to see which players are out clubbing late into the night -- Voulgaris watches virtually every NBA game. And he only needed to see the late-season Cavs play a couple of times to realize why they went reliably "over:" Point guard Ricky Davis, who was about to become a free agent, was forcing the pace to pad his stats and better position himself for a big contract.

"He had a hypothesis," Silver told me. "He looked for confirmation in the data and found it, and there was no reason to think it was going to change. You'll have that edge for maybe three days at a time until eventually the bookies catch on to it. But then you go find something else.

"There are probably a handful of people in the world who can do what Bob does and make a living at it. If he has a $30,000 bet riding on something and loses, he gets moderately upset. He wants to be right 56, 57 percent of the time. Which still means you're going to lose 43 percent of your bets."

As Silver writes, "Usually ... we focus on the newest, most immediately available information, and the bigger picture gets lost. Smart gamblers like Bob Voulgaris have learned to take advantage of this flaw in our thinking."

Silver's own thinking isn't nearly as Einsteinian as it might seem. "I don't usually have 'Aha!' moments," he says. "It's a lot of little things that add up." If a succession of tiny tweaks delivers improved accuracy on the margins, that's an advantage that Silver, like Voulgaris, is happy to harvest.

Since FiveThirtyEight partnered with the New York Times in 2009, politics has kept Silver preoccupied, but his sports pedigree still plays close to the surface. He'll paraphrase Charles Barkley in a discussion of election forecasting models, or slip a sports post into his blog every few weeks.

Here -- based on our conversation, his book, and his FiveThirtyEight posts -- is a glimpse into Silver's own thinking about a number of sports besides baseball:

• Soccer. In 2010 he developed the Soccer Power Index, a rating system of national teams, for ESPN. The SPI awards a staggering advantage of 0.6 of a goal to the host because referees tend to give more penalty kicks to the home side, and they tack on more extra time when the host finds itself trailing after 90 minutes. The SPI outperformed every other forecaster at the last World Cup -- except, Silver graciously points out, Paul the Octopus.

• College basketball. Silver's picks in last year's NCAA tournament beat the Vegas line, so when you fill out your bracket next March keep in mind two of his rules of thumb: One, the distance a team must travel to a neutral site has a high negative correlation with its performance; and Two, there's a steep drop-off in the strength of No. 1 and No. 2 seeds on the one hand, and the mass of marginally distinguishable teams seeded 5 through 12 on the other.

• The Olympics. On his blog Silver recently ran an experiment he called "Medalball:" If Oakland GM Billy Beane were put in charge of some Olympic equivalent of the A's, which sports should that "small-market country" concentrate on to maximize its return on investment -- or, if you will, its medals per Kyrgyzstani som? The answers, in order: wrestling, taekwondo and weightlifting. Each sport offers lots of medals, and distributes them among many countries, including poor ones.

• Pro basketball. Silver believes the New York Knicks should have matched the Houston Rockets' $25.1M offer sheet to Jeremy Lin last spring, and he was surprised when it turned out the Knicks weren't bluffing. He realizes now that his thinking stumbled on a flawed assumption about how Knicks owner James Dolan would behave. "The guy comes from the cable business," Silver says. "It's not a business where there's competition."

• Tennis. If baseball's 162 games reveal how a player performs "in the long run," tennis intrigues Silver because you reach "the long run" so quickly. "The very best players win only about 55 percent of the points they play," he writes. "However, hundreds of points are played over the course of a single match." He'd like to develop a U.S. Open app that updates winning probabilities in real time, to steer fans to the most competitive match in progress.

Right now Silver's PECOTA is imperiled by emerging digital programs like Pitch f/x, which can track in three dimensions over time how a pitch moves on its way to the plate -- in other words, literally tell you if Tim Lincecum has lost a foot on his fastball. "That was traditionally considered the domain of scouting," Silver says. "Now it's another variable that can be placed into a projection system. Someone will come along and figure out how to fuse quantitative and qualitative evaluations."

While that person may not be Silver himself, sports and games remain a passion -- so much so that he rues that the Olympics fall during election years. From his spontaneous reactions during the game we went to (a 4-3 Yankees victory over Baltimore), his preoccupation with numbers hasn't drained the fan from him. If online poker were ever legalized in the U.S., and it happened not to be an election year, "there'd be a lot of people who wouldn't know what they're doing," Silver says, "and I'd be tempted to drop whatever I was doing and play."

That would be our loss. But it's probable -- and if you spend any time around him you become highly sensitized to probability -- that it wouldn't be Nate Silver's.