Tragedy to triumph: The amazing story of the Ishpeming Hematites

Fourth down. The nose of the ball barely six inches from a first-down marker up ahead, but only 19 yards away from the end zone back behind. Barely four minutes left in last month's Michigan High School Athletic Association's Division 7 title game, at Detroit's Ford Field. The offensive team -- the Hematites from tiny Ishpeming High -- led 20-14. They have a decision to make. Punt or go for it?

Ishpeming's head coach, Jeff Olson, may have been in his 21st year of running the program, but the decision didn't come easy. He called time out and gave it thought. He reckoned that if his team went for it and failed, Loyola would be just 19 yards from scoring a touchdown; and afterwards, there wouldn't be much time left on the clock. Olson ordered the punting unit onto the field. Except that his players openly voiced their disagreement. "C'mon coach," they pleaded, "we'll get it."

In another time and place, the notion of the players disagreeing with Coach Olson -- at the end of the biggest game of their lives -- would have been laughable. And the notion of the coach relenting would have been funnier still. But in this sweet and bitter and wonderful and terrible upside-down, mixed up football season, it somehow seemed right.

Ishpeming burned a pair of timeouts, twice trying to draw Loyola offside. When that failed, the team's junior quarterback, Alex Briones, grabbed the snap off of a quick count, and, behind the team's 5-foot-10, 160 pound center, barreled ahead for the first down. Soon the time diminished to zero, Ishpeming had won the state championship. The players stormed the field and began the mother of all dog piles. In the stands, the thousands of fans who'd made the eight-hour drive down The Mitten of Michigan -- the equivalent of Chicago to Memphis, New York to Columbus -- hugged and cheered and shrieked.

On the field, Coach Olson took to a knee and then fell headfirst to the ground. For four months he'd held it all together, in the face of almost unimaginable tragedy. The entire fall was like one protracted staring contest with his emotion. Now, finally, he blinked. Actually, he broke down, sobbing convulsively while smiling with disbelief.

When the players saw their coach brought, quite literally, to his knees with emotion, well, most of them lost it, too. On this day anyway, there was crying in football. It was pointless to try to distinguish the tears of joy, the tears of anguish and the tears of relief. So they all just cried.

*****

You may have noticed the recent decline in the release of meaningful sports movies. Not that long ago, the Hollywood tastemakers offered us a regular diet of sports fare. Consider that Hoosiers, Bull Durham, Field of Dreams and The Natural all came out just a few years apart. Today? The few sports movies that make it to the Multiplex are mostly either crappy comedies or adapted versions of successful Michael Lewis books.

Where did the sports flick go? The accountants will tell that you that as international DVD sales became so important in the film business, sports were a tougher sell. The allure of ghosts in the Iowa cornfields or the Notre Dame walk-on got lost somewhere between Dubai and Shanghai. There's also the issue of licensing. When you simulate the NFL and the Washington Sentinels have to play the Phoenix Scorpions or the Dallas Ropers, we lose some authenticity.

But here's an alternative theory: sports are already the most compelling dramas and comedies and even tragedies, hitting on those crucial elements -- protagonists, antagonists, tension, conflict, redemption, resolution -- they teach at film school. Every day, at all levels, sports give us what we want from a good movie. If there's any sector of society that requires no fictionalizing and scripting, it's sports.

Which brings us to the banks of Lake Superior in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Ishpeming's listed population is 6,531, though residents put it closer to 5,000. It's a mining town, so much so that the high school team name is the Hematites, the mineral form of iron oxide. Many of the local adults work in the mines. Many of the local kids complain there's not much to do besides play video games, fish and hunt. "If it's four-legged and brown, it's going down," could pass for the town's unofficial motto.

For years Ishpeming was a basketball town, most of the 5,000 or so residents heading to the high school gym on Friday nights in the winter. But the allegiances switched to football in the '90s, and it's no coincidence: that was around the same time Coach Olson arrived.

Coach O. didn't exactly have access to a mother lode of talent. Even the best players on his teams were lucky to make the grade at a Division III college. (In two decades, no player under Olson has made the roster at a D-I school.) Two-way starters are the rule, not the exception. If you weigh close to 200 pounds you can count on being a lineman. Most of Olson's players look the way you probably picture them: pale, physically unremarkable kids with hair the length of freshly mowed grass.

Still, the program became a totem for the town. "I know from Steelers fans, but Ishpeming football is like nothing I've ever seen," says Gabriella DeLuca, a Pittsburgh native and cub reporter for the local Fox affiliate.

Olson just "had the touch," as one of the parents puts it. Moonlighting as the school's gym teacher, he knew most of the kids in town before they joined his team. From the beginning, he was a benevolent despot, at once authoritarian and approachable; flexible but tough. Though undersized, he was a former high school player in Marquette, Mich., and he made his teams in his image. "We just talk about doing things right all the time," he says. "If you have commitment and discipline you can be successful at anything."

Two years ago, in the fall of 2010, Ishpeming reached the state championship. The Hematites' star quarterback was Coach Olson's son, Daniel. At 5-8, 165 pounds, he was an all-state quarterback, the 2010 Offensive Player of the Year in the Upper Peninsula. A good chunk of his career passing yards came via one of his favorite targets, Derrick Briones. The team fell short in the final game, losing to Hudson 28-26. In the eyes of many -- including the team's admittedly partial coach -- Daniel Olson was the best player on the field that day. But that didn't seem to matter. For months, Daniel blamed himself for the defeat, waking up in sweats in the middle of the night to scold himself for what he perceived as a failure.

*****

Earlier this year, Sports Illustrated began a quest to find America's most inspiring underdog stories in high school football. A camera crew pinballed across the country. To Pahokee, Fla., where football is the escape from endemic poverty in the state's swampy midsection. To Fort Campbell High in Kentucky, where all of the players' parents serve in the U.S. military. To Fremont, Calif., where the team from the California School for the Deaf holds its own against the state's best.

The crew stopped in Ishpeming because an SI editor had happened upon the story of the team's backup kicker. Eric Dompierre had been born with Down syndrome, bearing an extra copy of chromosome 21, a genetic fluke that often slows cognitive function and generally stunts physical growth.

Eric hadn't simply assimilated. He was a fun and funny kid with plenty of friends, most of them having had his father, Dean Dompierre, as their fifth grade teacher. Eric would get a driver's license, blush when asked about girlfriends, swim in the lake with his cousins, and play sports. He joined the local youth football team after fifth grade -- "It was a chance to be one of the guys," he says -- and signed on to play for Olson once he got to high school. Apart from serving as a backup kicker, Eric was known for keeping the team loose. His signature move entailed tapping his teammates on the opposite shoulder, a prank that never seemed to get old.

One problem: Eric had been held back in elementary school. And a MHSAA rule dictated that kids can't participate in sports during their senior year if they turn 19 before Sept. 1. Dean Dompierre saw this coming. Starting in Eric's sophomore year, he began to petition administrators. The MHSAA initially declined the family's request for a rule exception. For more than two years, the family got the full tasting menu of bureaucracy. Hearings and subhearings, meetings and adjournments. Proposals and counterproposals.

Eric was no bystander or political pawn. He testified in Lansing and wrote movingly of what playing on the team had meant to him. His teammates were happy to testify and write letters of support, too. Last spring, representatives from Michigan high schools were finally allowed to vote on whether students with disabilities could play sports as seniors even if they had reached the age of 19. A full 94 percent of the schools approved the change.

This was, of course, classic underdog stuff: a father and his son, backed by their small town, standing up to injustice, righting a wrong. In June, the Dompierres were awarded a "Michigan Light" by a group honoring unsung heroes in the state.

When the SI crew arrived later in the summer, Ishpeming was still happy to talk about Eric, the team, small victories, and the importance of unity. "When you're winning together and losing together and going through different types of emotions, whether it's excitement or heartbreak, it develops a sense of pride in each other," Olson told the producer. "The best teams you have are the ones that are more family oriented that care about each other. When you care about somebody or something, good things can happen." Added R. J. Poirier, one of the team's seniors: "I have no doubt that this group, we'll be friends for the rest of our lives."

At the time, these were pleasant sound bites, if hardly unexpected for this kind of piece. Soon, we learned that remarks like these went much deeper. And so did the Ishpeming Story.

*****

In 2011, Derrick Briones, the star receiver of the team when Daniel Olson was the quarterback, died unexpectedly. The entire community was thunderstruck, not least the Hematite football players, many of whom had never before confronted the death of someone they knew. And among the players, Daniel Olson, Briones' quarterback and friend, was particularly rattled.

Daniel Olson cut the classic figure of a small-town hero, well liked by boys and girls in equal measure, physically solid. But internally, he could fissure. For years, he struggled with anxiety and bipolar disorder. There were stretches of darkness when he wondered why he was living. There were paralyzing panic attacks. Sometimes they were triggered by an event: the death of a friend, losing in the state championship game. Most times, like the fog rolling through a lakeside Midwest town, it came with little warning or predictability. More than once, he told his dad, "I don't want to die, but I just can't handle it any more." Some teammates knew that he was prone to dark intervals. But not all. "He could hide it," says his father. "Only a few people knew the extent of it."

Though never nearly as severe as in Daniel's case, the thread of mental illness ran through the family. No one ignored the symptoms. Daniel, especially, fought like hell. Medication. Therapy. Name a mental health professional in the Upper Peninsula and odds are good that Daniel visited the office. One went so far as to tell Jeff and Sally to prepare for the worst. "Your son," he said, "is dying."

After graduating from Ishpeming in 2011, Daniel went off to St. Norbert College in Wisconsin. He chose the school in part because it was a few hours away and the change of scenery might do him good. And in part because he could play football. Over the summers, he forced himself to work as a door-to-door knife salesman. His dad says that it was sort of aversion therapy, a way to force himself to confront some of his social fears, interacting with strangers.

But the thick fog still rolled in. One day Daniel called his parents from college and asked them to pick him up. The panic attacks had become incapacitating, lasting as long as 90 minutes, sometimes gripping him multiple times in a day. In 2010 and 2011, he had tried to commit suicide. The campus doctor had ordered him to go home "and rest your brain." A few weeks later, when he asked to return to school, Jeff and Sally resisted. Daniel grew teary. "I want to play football. That's what I want to do."

And then, on July 19, Daniel had gone fishing with his best friend and his brother, and then spent time with his sisters. He told the family he was going downstairs to the bathroom. After half an hour no one heard from him. Jeff went to the basement, walked into the laundry room bathroom, and discovered his son's lifeless body. "We tried everything but there was no hope," says Jeff. "I think that he would have died years before if he wasn't that tough and competitive."

There were no euphemisms and no obscuring details. Daniel had committed suicide, his parents explained. Even his obituary said plainly and unapologetically that "he passed away at his home in Marquette [MI.] following a long battle with anxiety and depression."

Two weeks before the start of the season and Jeff Olson had a decision to make: punt or go for it. Take some time off or coach. He recalled how sports had been his son's safe haven; maybe it would have the same effect with him, a way to at least defer his grief. But he also figured that he had a responsibility to the kids on the team -- not to coach them about blitz packages and spread offenses, but to help them get through another tragedy.

When the coach first gathered the team, he shared with them the coordinates on his personal GPS. He was a little lost, he admitted. They didn't cover situations like this in the coaching clinics. Then he said this: "Don't worry about me. I want you to talk about Daniel. I want you to talk about depression. I don't want you to be afraid of the word suicide. It's out there. This was Daniel's life and you guys are a spitting image of what he was about."

The players responded in kind. When Olson speaks about his son's suicide -- a loss unfathomable to most of us -- he's candid and matter-of-fact. His voice almost catches, though, when he talks about the small acts of kindness his players performed. On the night of the funeral, the team repaired to Coach's house; at 4 in the morning, half the players were still there, some camped out on the lawn. There was the time Alex Briones visited the family house. He got into his car to leave but turned around when he realized that he'd forgotten to hug the Olson's daughter, Taylor, and she might feel slighted. There were the impromptu bonfires, where the players sat around and talked about Daniel. No one called these gatherings self-organized group therapy sessions, but that's what they were.

Throughout the season there were no discipline issues, no kids getting suspended or into academic trouble. It didn't have to be articulated: if there were ever a season to avoid knuckle-headedness, this was it. "These kids had to grow up so quickly," says Jeff.

Last spring, Olson welcomed a transfer from Marquette, the neighboring town. A senior running back, Eric Kostreva, who had worn No.1 at his old school. At Ishpeming, No. 1 was taken; so he chose No. 11, which happened to be Daniel's old number. Kostreva knew Daniel from lifting weights together during the summers, and was happy to wear his friend's old jersey.

After the death, Kostreva offered his condolences to his new coach. And then he gathered his courage and made a request. "If it's okay with you, Coach, can I keep wearing Daniel's uniform this season?" he said. "I promise to represent the number the best I can."

The coach answered reflexively.

"Heck, yeah."

Their wrists covered in blue rubber bracelets reading:

R.I.P. D.J.O.7-19-12

The Hematites opened the season. During the tailgate before the first home game, fans were whipsawed between talking about Eric Dompierre and talking about Daniel Olson. In the stands parents brandished signs: "Do it for Derrick and Daniel." Instead of breaking huddles with the customary "1,2,3...team!" the Hematites sometimes chanted "1,2,3...Daniel."

A team -- an entire community, really -- in desperate need of some feel-good moments, got one during that home opener. Ishpeming ran up a sizable lead against the opposition, Manistique High, and trotted their 5-2, 125-pound, 19-year-old backup kicker onto the field to try an extra point. Eric Dompierre did what his parents, grandparents and cousins could not, and suppressed a grin. Thousands of fans linked arms. They all knew what it had entailed to get Eric into this position. He missed the kick, but the fight was officially over and Ishpeming had won.

On the sidelines, though, the Hematite players had a different response: we'll just have to score another touchdown and give Eric another chance. And they did. Again, Eric missed the kick. No problem. They'd just have to score another touchdown. The cycle played out three more times. One kick missed wide right. Another doinked the crossbar.

Then Eric came out for a fifth attempt with 4:59 left in the game. He cocked his left foot, addressed the ball and sent it cleaving the uprights. He was carried off the field on his teammates' shoulders, Rudy-style.

And then, as if the Ishpeming Story had gotten into the hands of a particularly sadistic scriptwriter, tragedy crept into the plot yet again. Christopher "Bubba" Croley was one of the best young football players in town, an eighth-grader sure to join the high school team next season. The players knew Bubba from football games, but most of them also knew him through his older sisters, who played on the Ishpeming varsity girls basketball team. On Friday, Oct. 5, the seventh week of the football season, the Croleys were driving south on Highway 141 to Wisconsin when their Chevy Impala collided head-on with a pick-up. The driver of the truck was allegedly drunk. Bubba Croley was pronounced dead on the way to the hospital. It was the day before he would have turned 14. (The other three passengers were injured, but survived.)

Ishpeming is filled with sensible, grounded Midwest types. But even the most rational of the locals wondered whether the town wasn't somehow cursed. For Coach Olson and his players, Bubba's would be the third funeral of a local football player they'd attend in barely a year. By now, they had the drill down. They'd show up the ceremony in their jerseys and pay their respects to the family. Then many would change out of their formal clothes, head down near the lake and start a bonfire, telling stories about another member of their peer group who'd left the world unacceptably early.

*****

We like to talk about the resilience and tenacity of athletes who manage to perform heroically in the face of horrible events. The Kansas City Chiefs' victory the day after a teammate orphaned his child -- killing the mother and turning a gun on himself -- is only one of the latest examples.

In truth, athletes, like most human beings, have tremendous powers of compartmentalization. When the quarterback is being blitzed, he's not thinking about a recent funeral. When an opposing receiver gets behind the coverage, the cornerback isn't dwelling on a personal loss.

Besides, the Ishpeming players said it over and over: the football field was a refuge, a place where they could come together and just be kids, where they could focus on a source of pleasure. Asked how much they were motivated by all the tragedy surrounding them, they offer a range of answers; but none says that it was a burden.

A Hematite team that was supposed to be good, not great, went 8-1 in the regular season. The Hematites then reeled off four wins in the postseason. Suddenly, they were in the state championship, the Big Game they couldn't quite win in 2010, when Daniel Olson was the quarterback.

It is here that the Ishpeming Story risks becoming almost too maudlin. In the final game, the Hematites faced Detroit Loyola, a private school powerhouse that was technically in the same division but, as an all-boys school, had a football talent pool twice as deep. Loyola had outscored its four postseason opponents 172-27; Ishpeming won its semifinal game by a score of 8-7. The average weight on the Hematites roster hovered around pounds; the Loyola roster featured a half dozen D-I prospects, including Malik McDowell, a 6-7, 295-pound behemoth of defensive end, currently the prize in a recruiting war between Michigan and Ohio State.

When the Hematites arrived at Ford Field, Olson could have been forgiven for asking his players to measure the yards of the field, in the manner of Gene Hackman instructing his Milan team in Hoosiers to measure off the 10 feet from floor to rim. The FSN-Detroit announcer opened the TV broadcast by announcing: "This is being billed as David versus Goliath."

Then the Hematites did what they'd done all season, playing whole-greater-than-sum-of-the-parts football. Though vastly undersized, the linemen held their own. The quarterback, Alex Briones, ran the offense with poise and efficiency. Eric Dompierre never got into the game -- "I wanted to put him in so bad," says Olson -- but he contributed in his own way. During a critical moment late in the game, he tapped Olson on the wrong shoulder, a pitch perfect bit of comic relief, a reminder that, ultimately, this was all supposed to be fun.

Oh, Eric Kostreva, the senior transfer who asked to wear No. 11 in honor of Daniel Olson? He scored all three of Ishpeming's touchdowns, rushing for 182 yards on 20 carries. ("He didn't go down the easiest," McDowell gamely told reporters afterwards. "He worked harder.") On defense, Kostreva made 16 tackles, a Division 7 championship game record.

Our scriptwriter got a little lazy at the game-ending scene. There was no dramatic winning touchdown or field goal or interception. Instead, on the last play from scrimmage, Ishpeming batted down a Hail Mary pass that was nowhere near the end zone, anyway. There it was on the scoreboard: Ishpeming 20, Loyola 14. ("Ishpeming Shocks Detroit Loyola" read the Detroit Free-Press headline.)

After he cried on the field, Coach Olson composed himself in the press conference after the game. "This group of kids is like family to me," he said. "We've had some tough times here, but these kids treated it like adults. They were around me when things were tough, but I'll tell you what ... This game is all about them. It's not about me; it is not about my son. It's all about them."

Now, a thoroughly unforgettable season would come garnished with a state title. Never have thousands of "Yoopers" been so happy to make an eight-hour drive back home. At the city's border, the Ishpeming firemen and policemen were waiting to escort the team bus.

It's about now that the credits start rolling. But the real Ishpeming story doesn't end quite so tidily. Without the distraction of football -- the daily practices, the team infrastructure, the games to anticipate -- a few dozen kids now have more time to process a pretty heavy set of circumstances. (Olson says one player has already approached him, asking him for help with depression.) Some will play basketball, including No.44, three-point specialist Eric Dompierre. But even then, it's different. They won't break huddles saying, "I,2,3 ... Daniel."

And the same goes for the coach. Olson sees how his wife, Sally, has been wrecked by Daniel's suicide. She just wants her son back. "She's struggling," he says, before his voice trails off. Without football and with the pace of days slowed, how will he do when he stands back and looks at the past few months with a sort of analytic detachment? Can he come off this high, he wonders aloud, without crashing?

Still, as recently as last week, the team's Season of Magical Thinking continued playing out. Of all the high school programs nominated in the Underdog program, Ishpeming received the most first-place votes from online readers. (Mind you, the voting was based on Eric Dompierre's battle with Michigan administrators. Had fans known all the contours of Ishpeming, the school wouldn't just have won in a landslide; the award would be retired in its name.)

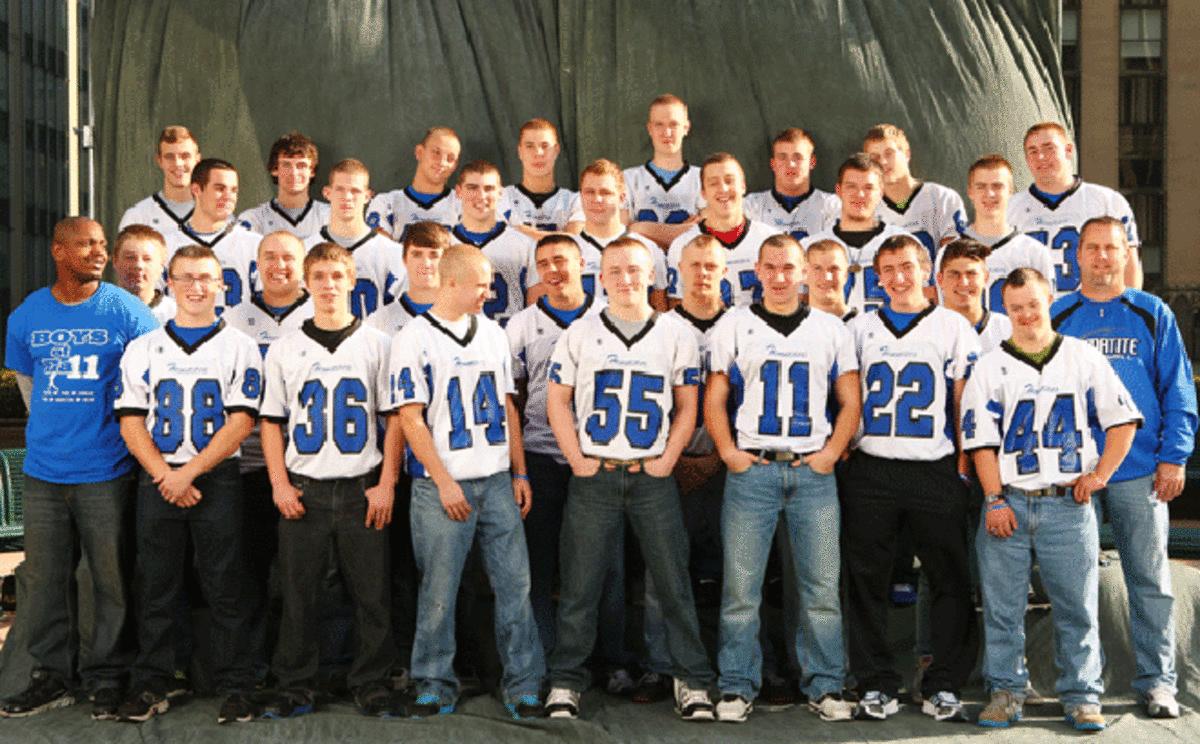

In addition to winning a $25,000 contribution to the school from Powerade, the program's sponsor, 10 players and coaches were invited to fly to New York for last Wednesday's SI Sportsman of the Year ceremony.

Coach Olson and Dean Dompierre agonized over which players to invite, apart from Eric Dompierre. It was the equivalent of splitting babies. "The whole helped Eric," Dean Dompierre kept saying. Added Coach O: "This whole season was such a team effort." So they offered a proposal. Instead of flying a few players, what if they applied the cost of airfare to renting a charter bus so the whole team could attend?

Heck, yeah.

So it was that Olson, an assistant coach, Dean Dompierre, DeLuca the local TV reporter, and 29 teenagers boarded a bus at noon on Dec. 3. They spent the next 22 hours chugging down state roads and across interstates. They watched Dark Knight and Friends With Benefits and Anchorman; they played with their iToys; they talked and wrestled and looked out the window and snacked heroically and didn't sleep much. Finally, they arrived in Manhattan at around 10 the following morning. For all but two of the players -- one, an exchange student from Italy; the other an exchange student from Finland -- it was their first time in New York.

They wore their football jerseys proudly around town. Whenever they were asked, as they inevitably were, "What's a Hematite?" they were all too happy to provide the answer. They would stay at the same trendy hotel where Lindsay Lohan recently got arrested. They would go to Ground Zero and first-bump LeBron James at the SI Sportsman gala.

But they also had some free time. Not long after they got off the bus in the middle of Midtown Manhattan, the kids from Small Town, America were asked what they most wanted to do in the Big City. A clot of players pointed in the direction of the famed holiday display at Rockefeller Center. "We want," they said, "to see the lights."

You might argue that they'd done that already back in Ishpeming.