The General Whose Army Never Wins

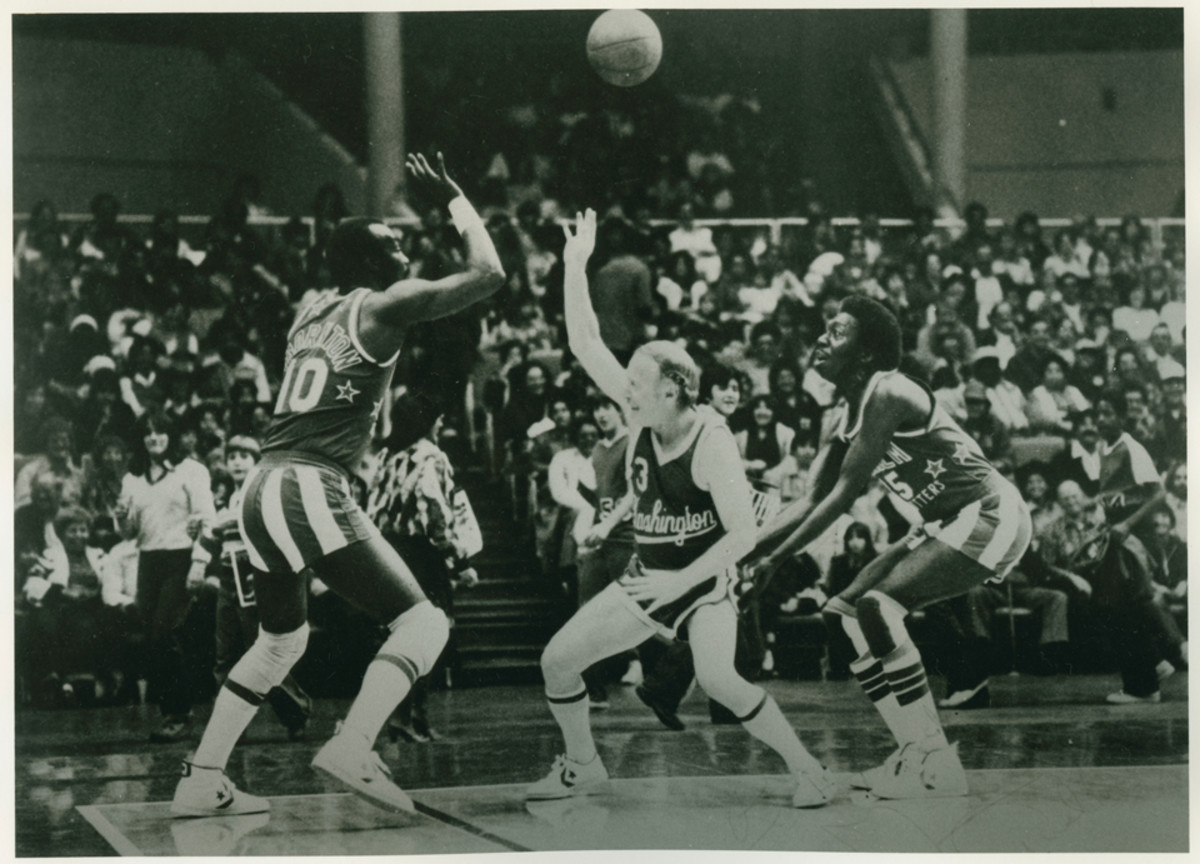

In a life of losing to the Globetrotters, Red Klotz of the Washington Generals has won over the world

On Saturday, July 12, Louis "Red" Klotz passed away at the age of 93. Klotz was the architect behind the Washington Generals and many other teams that traveled with, and lost, to the Harlem Globetrotters. This story originally appeared in the February 20, 1995 issue of Sports Illustrated.

Red Klotz has lost basketball games in front of four popes. He has lost on an aircraft carrier. He has lost in a leper colony. He has lost in South Korea. He has lost in South Dakota. He hasn't lost in South Africa yet, but he's hopeful. He has lost in 113 countries (he is, he boasts, the first American to lose in China). He has lost in 1,341 towns in the 50 states. He has lost somewhere in the neighborhood of 13,000 games, the last 7,968 in a row, give or take a few. In the time it takes to read this paragraph, he could easily lose another one. ''I'm the losingest coach in the world,'' says Klotz, the 74-year-old coach and owner of the Washington Generals. ''But I'll never get fired. Pretty amazing, huh?''

What do you ask a basketball coach who has lost 7,968 straight games -- to the same team -- as he prowls around the locker room preparing his pregame speech? Excuse me, Coach, any changes in the game plan tonight? After all, the enemy is the Harlem Globetrotters. So naturally you wonder: Why doesn't Klotz tell his guys to watch out for the ball-under-the-jersey trick? Or the Figure Eight? Or the yo-yo ball? Or the half-court hook? For god's sake, boys, D-up when you hear Sweet Georgia Brown!

It's a tribute to all 67 inches of Louis Herman (Red) Klotz that he has resisted the urge to fire himself. To be the coach of the Washington Generals is to prosecute a case against Perry Mason. Or to chase the Roadrunner. With only one victory, Klotz's alltime winning percentage as a former player and current coach of the Generals is .0000769, which is right down there with Charlie Brown's. Heck, a Red Klotz business card features a stencil of a tall guy in Trotters trou dunking over a helpless dwarf.

Red Klotz. Even the name is a 200-to-1 shot. The surname is a hybrid of clod and klutz. The full title sounds less like a name than a symptom. Bad news, Mr. Goldstein, your red klotz are down this month. In fact, many Globetrotter fans assume that with a name so ludicrous this Klotz guy must be a character carefully created to lead the losers. A man once came up to Klotz in the early '70s and asked him, ''Are you the original Red Klotz?''

Klotz still laughs at himself telling this story. Maybe he recognizes the irony. Maybe not. Because in many ways Red Klotz is a cartoon character who has come to life, having tied up Louis Klotz, bound his hands and feet, gagged him and left him struggling in the boiler room of a gym somewhere in Borneo. As you talk to this Klotz, you are disturbed by the feeling that he can only be viewed in two dimensions; you have an almost uncontrollable urge to peek behind him, where you expect he is being propped up by a two-by-four. You expect to find a tape recorder strapped to his back because he tells exactly the same stories, word for word, that he did 20 years ago. His references are still peppered with names like Neil Armstrong and Douglas MacArthur, heroes of days gone by. He has never bothered to update them.

Klotz brushes off all the personal questions as part of the myth, part of his secret. So you inquire about close friends who might provide some insight, but after Klotz thumbs through his mental Rolodex, he finally allows that he can't come up with anybody right this minute, but he'll be happy to get back to you with names next week. Of course, next week he's in Qatar. Klotz has lived his life on the lam, darting from town to town, a satellite outside any social circle. His favorite statement is the one about how he has run more miles on a basketball floor than any other human. Running, yes. He's always running away from life's routine. Hardly ever stopping to think. Forty-two years ago Louis Klotz ran away with the circus, and Red Klotz has never really come home.

Klotz on loss No. 47: ''Back in the early '50s I took my team to play in front of the shah of Iran, who had survived about 100 attempts on his life, so everybody was a little jumpy. When we got to the court, I realized I had forgotten the basketballs, so I ran back toward the bus to get them. Suddenly I heard this bloodcurdling scream, and this guard jammed a gun barrel in my stomach. If I hadn't stopped, the guy would've turned me into Swiss cheese. It was a scary moment, but when I looked back at my players, they were all giggling hysterically. I'm afraid we lost the game, but I had to look on the bright side . . . nobody died.''

It's in the face of overwhelming odds that Klotz has walked into thousands of visitors' locker rooms. On this day he has agreed to be shadowed for a 300- mile round-trip bus ride and two games, an afternoon contest in New York City and a nightcap in New Haven, Conn. So this particular locker room happens to be in the bowels of New York's legendary Madison Square Garden. It could be anywhere. Klotz's speech is always the same. It should come with subtitles: ''O.K., boys, let's play solid defense. (Don't screw up the Figure Eight.) Play within yourselves. (Never, ever upstage the Trotters.) Let's have some fun out there. (Be sure to giggle when your shorts are pulled down.) Let's go win. (Let's go win.)'' Yes, it sounds crazy, but when Klotz says he wants to win, he really means it.

As Klotz talks, Billy Kurisko, who is about to play his very first game with the Generals, is sneaking peeks at his new teammates. Kurisko has just completed a crash course in how to tiptoe through the Trotters' famous Figure Eight without getting beaned by the ball, and now Klotz is exhorting him to kick some Trotter tail. Kurisko turns to teammate Ed Hepinger and whispers, ''Is this guy serious?''

Klotz insists that Abe Saperstein, who founded the Trotters in 1927 and handed the reins of the Generals to Klotz in 1953, never once asked him to take a dive. And Klotz swears on his one and only victory (more on that later) that his team plays all out . . . except during Trotter routines. ''I tell my players that our first priority is always the laughter,'' says Klotz. ''We're the straight men. Laurel had Hardy, Lewis had Martin, Costello had Abbott, and the Trotters have us. We're not stooges, we're not losers at heart, but let's face it, who got more glory, Abbott or Costello?''

Klotz leads his team out to the Garden floor, and despite a barrage of ) advice from him, the Generals are thrashed soundly. Kurisko does not get hit by the ball in the Figure Eight, but he does laugh out loud when a Trotter gooses Hepinger. Rookie mistake.

As the game gets ugly, Gloria Klotz, who sits on the team bench clad in mink coat, fedora and cowboy boots, starts to jot down answers in a book of crossword puzzles that she keeps carefully concealed beneath her scorebook. Gloria has been Red's wife for the last 53 years and his scorekeeper for the last 10, and it is generally understood that when she says something like ''Anybody got a five-letter word for long-snouted omnivore?'' the Generals have officially folded their tents for the night. The final score is Globetrotters 68, Generals 56. Though the Generals flew in from Boston through a blizzard the previous night and arrived at their hotel in Secaucus, N.J., at 3:30 a.m., they still face another bus ride and another loss, uh, game that evening.

Loss No. 3,456: ''We were playing in a leper colony somewhere in the middle of the Philippine jungle, and all that separated us from the fans was a chicken- wire fence. I remember I could hardly dribble for fear that I would start itching and a limb would drop off right there on the court.''

Louis Klotz met Gloria Stein one sunny day in 1934 on the beach in her hometown of Atlantic City. Louis was 14, Gloria 12. Back in South Philadelphia where Red lived, he played hoops because he had to. ''Where I was raised, you either earned a scholarship to college or became a gangster,'' he says.

Louis's parents, Robert and Lena, didn't approve of their youngest son playing basketball, fearing that a nearsighted 5 ft. 7", 140-pound kid could only get hurt. So Louis would drop his gym bag out of his bedroom window, walk out the back door, then change his clothes in the back of the trolley car. He fine-tuned his classic two-handed set shot by launching it through the rafters of St. Martha's church on Eighth Street and honed his ball handling on the playgrounds of hardscrabble South Philly, where he earned the nickname Reds (later shortened to Red) because of his tangerine-colored locks. While leading Southern High to city championships in 1939 and '40, Klotz was twice voted Philadelphia's player of the year.

His local fame earned him a scholarship to Villanova, where he played for two years until it was discovered that he and Gloria had eloped during his freshman year. School regulations dictated that the marriage cost him his financial aid. By that time World War II was raging anyway, and most of Villanova's team had enlisted. Red, whose eyes were so bad that he couldn't have spotted Mussolini if he had been standing beside him, was tapped for the Signal Corps. His roommate and best friend at Villanova, Chuck Drizen, entered the Marines and in a prescient letter to Klotz in 1944 he wrote, ''Reds, you're going to go very far with basketball.'' It was the last letter Klotz would receive from Drizen, who was killed at Iwo Jima.

After the war Red joined the Philadelphia SPHAs (South Philadelphia Hebrew Association) of the American Basketball League, a predecessor of the NBA. He played two seasons for the SPHAs before hooking up with the NBA's Baltimore Bullets midway through the 1947-48 season. He played in 11 games (averaging 1.4 points) for the Bullets, who went on to defeat the Philadelphia Warriors in six games to win the NBA title. ''It was a thrill to be a champion,'' says Klotz, who earned $100 a game and received a $1,750 title share. ''But in the off-season we all wanted raises, so they canned us.''

Klotz eventually returned to the SPHAs, who in 1949 were hired to play a two-week exhibition series against Abe Saperstein's barnstorming team, the Harlem Globetrotters. One evening, playing on the dance floor of Philadelphia's Broadwood Hotel, Klotz's SPHAs upset the Globetrotters by 25 points. After the game Trotter Goose Tatum approached Klotz, waving a finger in his face. ''That'll never happen again,'' said Tatum. Klotz responded, ''Why not?'' Sure enough, the next night the SPHAs beat the Trotters in Syracuse by 12.

Saperstein was so impressed that he offered Klotz the opportunity to form a team to be the regular opponent of his Trotters. In 1953 Klotz received a $1,500 loan from Saperstein, and he and his squad drove from town to town, all eight of them crammed into a beat-up green DeSoto. The owner named his new team the Washington Generals. ''Ike had just thumped Adlai Stevenson, and generals were pretty popular at that time,'' says Klotz. ''I thought the name might win us some fans.''

Loss No. 6,787: ''We were playing a game outdoors in Germany, and it had rained quite a bit recently. The court was a quagmire, so they brought in hundreds of beer kegs and laid out plywood on top of the kegs. Sure enough, it poured again on game day, and it was so slippery that my players kept skidding right off the end of the court into a giant mud puddle. The fans loved it. They thought it was part of the act.''

After more than 40 years of bus trips, a little snow shower on Interstate 95 heading north to New Haven doesn't faze Red Klotz. He is on the edge of his seat, telling his companion about some of the natural disasters he has encountered during his 12 circumnavigations of the globe. He has survived three earthquakes, two floods, one avalanche and one appearance on The Arsenio Hall Show! ''I'm definitely living on borrowed time,'' Klotz says.

Klotz has always considered himself the United States Basketball Ambassador to the World. Among the A-list dignitaries before whom Klotz has bowed in the name of goodwill are Queen Elizabeth II; popes Pius XII, John XXIII, Paul VI and John Paul II; Prince Rainier; Evita Peron; and Nikita Khrushchev. His favorite road story concerns his misadventures after a 1953 game in Syria. The tour was leaving for Istanbul, but the airplane was overweight, so Saperstein ordered Klotz, two Generals and two Trotters to get off. They had to drive 100 miles to Beirut to catch another flight . . .

". . . so I get stopped at the Lebanese border," says Klotz, "and everybody is running around like crazy with machine guns, getting ready to go to war with Israel for the umpteenth time. I'm trying to identify myself by pretending to dribble and shoot, but the guards just keep looking at my visa list that has 42 names on it, and they want to know where we've buried the bodies of the other 37 guys. It didn't help much that the first two names on the list were Saperstein and Klotz. . . .''

Just then, when it appears he might recount the ultimate loss, the storyteller pauses to point out a favorite landmark along the broad shoulders of the Connecticut Turnpike. Klotz will get you back to Lebanon eventually, but he wonders why you are so anxious because, after all, you both know the hero has lived to tell about it. And besides, if you look out to your right, there's a lovely view of Long Island Sound. Klotz is constantly staring out the window as he dispenses his life and times, and just at the point when he realizes he's losing his audience, he will punctuate an anecdote by saying, ''True story,'' the way baseball clown Max Patkin always did.

You realize that Red Klotz's story is a lot like Patkin's, only with a happily-ever-after attached. Klotz is unaware of Patkin's pathos, so you tell him about how the Clown Prince of Baseball grew to resent the road, how he lost his wife and was driven to the brink of suicide, and Klotz shrugs and struggles to conjure up any angst of his own. You hate to do it, but you ask this father of six about all those Little League games he missed, those graduations, all the prom nights he heard about through a telephone receiver, and you expect maybe even some tears. You are incredulous to learn that Klotz doesn't look at his career as that much of a sacrifice. You are even more incredulous that his kids don't revile him or treat him like some sort of Daddy Dearest but instead revere him. But most of all you are incredulous that after all these years on the road, Klotz still looks out the window.

''He's been away all my life,'' says his daughter Jody, 40, his youngest child. ''Still, somehow Dad was always there for us. He called home every night, and we never had to worry about someone coming between us, because when you love basketball as much as Dad does, there isn't room for anything else.'' Says Red, ''It's a cycle, just like a sea captain's. He loves his wife and kids and misses them, but when he gets home, before long he can't wait to get back out to sea. It's a sickness, but a beautiful one.''

Loss No. 10,314: ''We were playing in Peru, and the night before the game we were in a bar when a fight broke out and the army had to intervene to get us out of there. The next morning the headlines read: GLOBETROTTERS ATTACK PERUVIANS. So it was very tense before the game, and the fans actually booed the Trotters. But as the game began and the Trotters started their antics, the mood changed. By game's end it was all back to normal, the fans were booing us mercilessly . . . gosh, what a relief.''

''I'm the greatest three-point shooter on the planet,'' says Klotz, as he buries treys during a shootaround before the start of the day's second game at the New Haven Coliseum. When he is presented with alternative suitors to that title, Klotz points to a similar shootaround in June '92 at The Palace in Auburn Hills, Mich., when he sank 21 straight from behind the old NBA three- point arc. You wonder how he does it with that archaic two-handed style. Klotz attributes his skill to single-minded focus: ''When I shoot the two- hander, I think I'm standing on an island and 10 million people all around me have disappeared.''

It was this two-hander that often kept the Generals within shouting distance in games. Klotz, who scored as many as 37 points in a game, is still the most dangerous marksman the Generals have ever recruited. ''If Red was coming out of school today, he would definitely play in the NBA because he's got one of the best three-point shots I've ever seen,'' says the Trotters' longtime funnyman Meadowlark Lemon. ''He was tough in his day, even though he was this little midget among the giants. It was like David and Goliath, except David wasn't winning.''

But the part of Klotz's game that he developed most was his comedic timing. Nobody executed a triple take like Klotz, who for his art regularly endured having his butt pinched, his armpits sniffed or the indignity of trying a layup while toting a ladies' handbag. And he embodied the classic elements of the oppressed. ''With Red you lose on all sorts of counts,'' says Wilt Chamberlain, a Trotter in his off-seasons in the 1950s and '60s. ''You can't hit a man with glasses, you've got to pick on guys your own size, and you must always respect your elders.''

Although he still carries his uniform in a gym bag to every game, Klotz finally ''retired'' to the sidelines eight years ago at the age of 66. He has since tried to pass on the mantle of chief foil, but, typically, none of his players has quite been able to handle the pass.

In New Haven, Klotz's task is even more challenging than usual because the Generals have picked up two guest players, a pair of local radio deejays, who are both short, paunchy and wearing thick-soled jogging shoes. Nonetheless, the Generals actually take a four-point lead early in the first quarter. Soon, though, order is restored, and the Generals are eventually clobbered by 26 points. What's worse, the time-honored water-bucket stunt bombs when a meddlesome kid announces to all of section 113 that the pail is actually filled with confetti. Says Klotz in summation: ''In coaching and comedy, you're only as good as your material.''

Win No. 1: ''The fifth of January 1971. University of Tennessee at Martin. I remember it like last week. My team played great that night, and we were up 12 with two minutes left, but the Trotters stormed back to take a 99-98 lead with 30 seconds to go. I called timeout and told my team I wanted the final shot. With 10 seconds left I took a two-hander from 20 feet. Swish. Then Meadowlark's final shot rimmed out. We won. Everybody was stunned. Let me tell you, beating the Globetrotters is like shooting Santa Claus. Later the press blamed the loss on the clock operator who hadn't stopped the clock during / Trotter routines early in the fourth quarter. Could be. The timekeeper's name was Chuck Klotz.''

In recent years Red Klotz has agreed to take a sabbatical now and then to return to his beach house in Margate City, N.J., where he can make up for lost time with Chuck, his other children and his 12 grandchildren. In Red's absence, his son-in-law John Ferrari coaches the team. The man who stands to inherit the Generals someday doesn't expect that to happen anytime soon. ''I know in my heart that Red will never retire,'' Ferrari says. ''If you pop his car trunk, the only stuff in there is a beat-up pair of sneakers and a basketball. When the car's gone, you know he's at the playground.''

During the summer months when Boston Celtic coach Chris Ford returns to his boyhood home in Margate City, he drives over the tiny toll bridge and down Jerome Avenue past the town park where there is a fixture almost as permanent as the rusty basketball rims and the cracks in the asphalt. There is Red Klotz, like Updike's Rabbit Angstrom, the aging former basketball star who has outlived his competition. He is shooting that crazy two-handed set shot, alone on his island. ''Whenever Red hurls up that two-hander, at first the kids are all taken aback, but after a while they're in awe,'' says Ford, who resides two blocks from Klotz. ''He's a living legend.''

Two of Klotz's jerseys -- one General and one SPHA -- have made it to the Basketball Hall of Fame. Klotz has not. Springfield doesn't usually cast busts for busts. ''I guess Red's legacy is in how he's touched my life and the lives of all his players,'' says Sam Sawyer, a General from 1958 to '75, who then became an Atlantic City cabbie and part-time Klotz teammate on the playground. ''It's like Red knows the secret to happiness.''

''Think of it like this,'' says Klotz. ''The other night we played in Fresno, and it was a typical game, we kept it close right to the end, but we lost the game by six. We made it exciting, though, and the fans got a few laughs, and to me that's just as good as a win. If you look at it that way, I have a pretty good record.''

Red Klotz admits he might win again. But he is more concerned about finding new, more exciting places in which to lose. Already he has lost in a bullring. He has lost in the deep end of a swimming pool. He has lost in front of 75,000 German fans. He has lost in front of an audience consisting of just a Paraguayan plantation owner and his family. But as a rational observer, you * still can't help wondering why once, just once, Klotz doesn't tell his guys to look out for the wobble-ball trick? Why? Why? Why? . . .

Then you bite your tongue because you realize you've asked that one a hundred different ways already and he keeps answering it the same way. His way. You are tempted to grab him by the lapels, shake him, tell him that of all the people on earth, he is the one who couldn't be faulted for saying, It is whether you win or lose, and how you play the game is so much poppycock. But you think better of it.

You figure out that Robert and Lena Klotz had nothing to worry about. That Red Klotz has never needed a third dimension, that he has always known that what he lacked in length and width he would not need to make up in depth. He has simply tried to do exactly what other fathers try to do. He is just another working man, a factory foreman who toils every day at the head of basketball's assembly line, mass-producing losses and laughs and lessons, and, unlike most foremen, enduring some hellacious business trips. Suddenly you realize that is his big secret: He is just a guy doing his job, and his job is to make people laugh.

''We have a way in this country of worshiping winners,'' says Klotz, as the bus pulls out of New Haven. ''Kids today are taught from Little League on up that they must win. But only one team can win, so most of us are losers in a way. My team is learning an important lesson about life.

''I guess that's why I don't worry too much about being the losingest coach in history. It's like if you come home at four in the morning and you hear the milkman whistling on the job and you wonder what he's so happy about. It's because he understands his purpose.''

Says Meadowlark Lemon, ''You never lose when you bring joy to people, when you put a smile on a face that lasts forever. People used to come up to me all the time after games and say, 'Hey, Meadow, that little, old red-haired guy is wonderful.' So if anybody calls Red a loser, they're missing the whole point. When a Globetrotter game is over, folks never remember the final score. People remember the laughter.''