How Peanuts' Peppermint Patty became a fierce advocate for female athletes

Years before Justine Siegal became the first woman to coach in Major League Baseball, she began her days with a paper route, breakfast and the funnies page of the newspaper.

One of her favorite comics was Peanuts. Like the characters of Charles Schulz’s beloved strip, Siegal spent many childhood afternoons on a baseball diamond, playing pickup ball with kids from the neighborhood. But while Charlie Brown and Snoopy are the most prominent faces of a global brand, the character Siegal most identified with was Peppermint Patty.

It isn’t hard to see why. Peppermint Patty was a huge sports fan—she once replied to a teacher’s question about the four seasons by listing “baseball, football, basketball and hockey”—and an even more committed athlete. Introduced by Schulz in 1966, she was quickly established as the best athlete in the strip, boy or girl (or dog). She managed a baseball team only a few years after girls in America gained the right to play Little League.

Siegal, who made her MLB coaching debut with the A’s in 2015, initially didn’t realize Peppermint Patty was a trailblazer. Peanuts made it all seem so normal.

“There’s not arrows pointing—see, there’s a feminist!” Siegal, now 41, says. “Charlie Brown never thought twice about having a girl on his baseball team. A lot of it just seemed normal, at least to me. That was my life, being a girl on a baseball team, playing with the neighborhood kids. Looking back on it, Peppermint Patty was before her time for sure.”

For 50 years, Peppermint Patty has been a cultural icon for women and girls trying to find their place in a sports world dominated by men. She’s fictional, of course, but she speaks about the reality of sexism in sports with fervor and eloquence. In popular culture, no other character has been so vocal about gender inequality on the field.

On Aug. 22, 1966, Schulz introduced Patricia Reichardt, almost always referred to as Peppermint Patty, to his strip, which at that point had been published for nearly 16 years. “I got the idea for her name after looking at a dish of candy on my desk and decided that 'Peppermint Patty' was such a great name that I just had to use it before some other cartoonist beat me to the idea,” Schulz, who died in 2000, once said. Peppermint Patty may owe her debut to a candy bowl, but it was hardly a coincidence that her introduction coincided with the emergence of the women’s liberation movement.

At first glance, Peppermint Patty might not resemble your idea of a crusader for women’s rights. Most obviously, she’s just a kid, like every other character in Peanuts—besides Snoopy, Woodstock and other non-humans—and kids don’t often crusade against structural inequalities of our society. This is the magic of Peanuts: Schulz’s characters simultaneously possess the wisdom of age and the innocence of youth. Perhaps the best example of this dichotomy is Linus opining on religion and philosophy while holding his “security blanket.”

Brunette and freckled, Peppermint Patty’s green blouse and trademark sandals may have appeared just as unassuming, but it's no accident that she was the first female Peanuts character whose standard outfit wasn’t a dress. Peppermint Patty is quickly revealed as a quintessential tomboy: In her Peanuts debut, she tells Roy that she might have to “clobber” him when they Indian wrestle.

Her penchant for independent thought sometimes fosters unintentional comedy: She calls Charlie Brown “Chuck” (nobody else does this) and refers to Lucy as “Lucille” (ditto), bewildering both of them.She’s uninterested in school, which her trademark “D-” grade reflects. She’s oblivious to the point of absurdity: She admires Snoopy’s baseball ability but calls him the “funny looking kid with the big nose,” unaware for a number of years that he is a beagle. Peppermint Patty is also an only child to a single parent, her father, after her mother died when she was young. This girl would ultimately take aim at the patriarchy of sports, leading a passionate Peanuts campaign championing gender equality on the field.

Any fan of Peanuts—and there are many of us, with roughly 355 million people in 75 countries reading the strip at its peak—can attest to Charles Schulz’s passion for sports. Besides his fandom, Sparky (as Schulz was known) was an avid hockey player. Charlie Brown, Snoopy and the rest of Schulz’s characters are often shown playing sports, but triumph is ephemeral. Charlie Brown’s foot is never able to make contact with the elusive football, and his baseball team makes the ‘62 Mets seem formidable by comparison.Snoopy’s a star athlete, though sometimes only in his imagination.

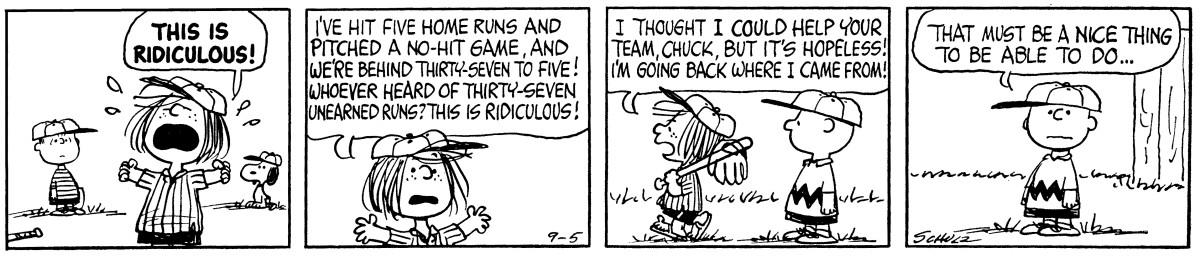

Peppermint Patty, however, doesn’t like losing—and her tremendous ability backs up her competitiveness. This becomes clear soon after her debut, when she joins Charlie Brown’s baseball team. She’s determined to show “Chuck” how to win, but she quickly realizes the team is hopeless.

Peppermint Patty’s mere presence in the strip as a strong female athlete was powerful.

“Schulz kind of tapped into what was going on at the time period, but he also presented people with this athletic female role model that I think did a lot to change the way people think, even if it was just making them feel better about their own athleticism,” says Penn State professor of kinesiology Jaime Schultz, who studies the history of women in sport.

WNBA 20: Two decades of defining storylines as players remember them

Peanuts was rarely overtly political, but Schulz’s social consciousness still influenced his work. Several of his female characters, such as the outspoken Lucy—who also played sports, albeit somewhat reluctantly—challenged conventional views on femininity. Schulz’s introduction of sports-crazed Peppermint Patty, on its own, was not going to change institutional sexism. But for Justine Siegal and so many other women, Peppermint Patty helped affirm, on a personal level, that they belonged on the field.

“I love her personality. It reminds me of me when I was just a young girl,” says Kathryn “Tubby” Johnston Massar, who broke Little League’s gender barrier in 1950. “One that wanted something and went after it. Why should this be allowed just for boys? I’m just going to get in there and play along with him. That’s the way Peppermint Patty was. Even if they say it’s not a girls’ game, that it’s for boys, she’s going to do it.”

Female athletes were breaking through in the real world, but the accessibility and relatability of Peanuts made the strip a powerful tool for helping to normalize the female athlete, to both male and female readers. Pop culture can challenge stereotypes about society in a unique way, and Peanuts succeeded in doing so.

“You get more people to think more critically about their social world by doing so in a space that seems relatively innocuous. It’s a comic strip, but Peppermint Patty is now saying this. It’s not just this kind of angry feminist Gloria Steinem,” says Purdue University professor Cheryl Cooky, who studies the intersection of gender, media, sports and pop culture. “It’s not just information that is being conveyed by a minority, but now it’s in my newspaper, it’s in a comic strip of which I’m a fan. So in that sense, it challenges people’s perceptions or at least is a form of advocacy that is getting the information out and is educating people and making them aware.”

When Peppermint Patty debuted in 1966, America still viewed the female athlete as an oxymoron. That same year, Bobbi Gibb became the first woman to finish the Boston Marathon—but she was only able to run the race by hiding her gender. Opportunities for women in sports were limited.

In 1972, the passage of Title IX started to change everything. A statute of the Education Amendments of 1972, Title IX banned gender discrimination in any federal educational activity or program. The law, in theory, promised greater opportunities for female athletes, even though the legislation originally made no mention of athletics. But while today the law is considered one of the great legislative achievements of the women’s rights movement, the backlash was swift.

During the 1970s, Congress considered several amendments and bills to limit the scope of Title IX, while the NCAA launched a legal challenge in 1976. Some conservative politicians raised concerns over the federal government meddling with local educational decisions. The NCAA and even several prominent college football coaches worried about the impact of Title IX on revenue sports like football and basketball. In June 1975, high-profile coaches like Texas’s Darrell Royal and Michigan’s Bo Schembechler testified against Title IX to a House of Representatives education subcommittee.

Despite a volatile first few years, Congress did not immediately enact any serious changes to Title IX following its passage, most prominently rejecting the 1974 Tower Amendment, which would have exempted revenue sports from the law. In December 1979, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare published its policy interpretation, which set forth guidelines on how academic institutions could comply with Title IX. But contention over Title IX and other potential legislation designed to elevate the status of women in society was just beginning, particularly as states considered the Equal Rights Amendment, a proposed constitutional amendment to codify equal rights for women.

Becky Hammon leading revolution for women in men's professional sports

It was in this political climate that Charles Schulz decided to enter the fray. A few years after Title IX was signed into law, Peppermint Patty’s sense of injustice fueled a vigorous Peanuts defense of Title IX.

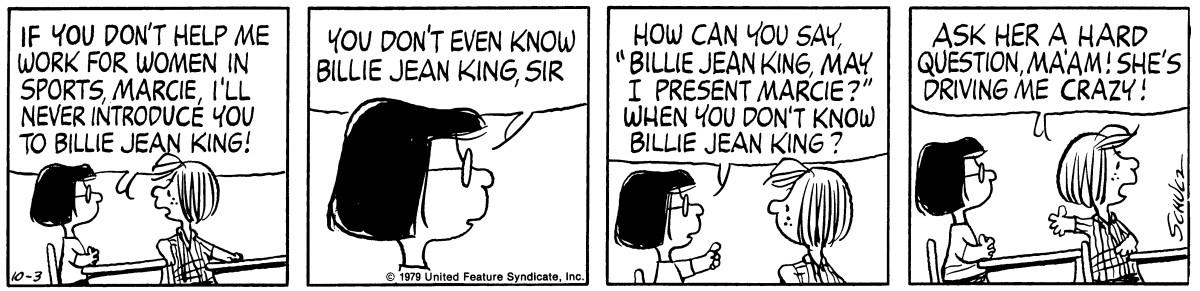

Like so many important moments in women’s sports history, it started with Billie Jean King.

In 1974, the year after the famed “Battle of the Sexes,” King founded the Women’s Sports Foundation to promote female participation in sports and fight for gender equality on the field. Soon after, she met Schulz.

King and Schulz were mutual admirers before they met, and the two quickly became close friends. King, who Schulz mentioned in a number of strips, regularly drove to Santa Rosa, Calif., where Sparky lived and worked, to visit with the cartoonist. They’d spend hours together, talking over tuna sandwiches, root beers and chocolate chip cookies.

“We would sit and talk about the world and try to get the world right,” King says.

Schulz was known to be quiet and introspective, but he soon formally aligned himself with the women’s sports movement. In 1976, he joined the board of King’s fledgling foundation—just as the fight to lessen gender inequality on the field started to intensify.

“His willingness to become a trustee, which meant coming to meetings and all of this stuff, was a measure of just how passionately he felt about what we were trying to accomplish,” says Holly Turner, the former associate executive director of the Women’s Sports Foundation and a friend of Schulz. “I honestly think that Sparky saw it as something that would change the world. If we could achieve what we were setting out to achieve, that this would change the status of women in the world.”

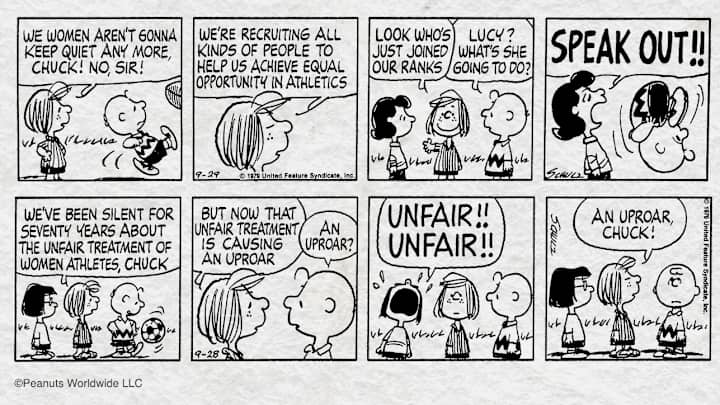

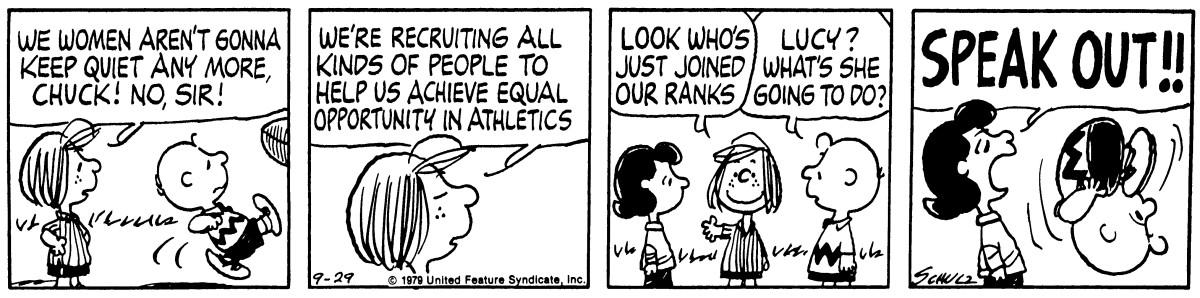

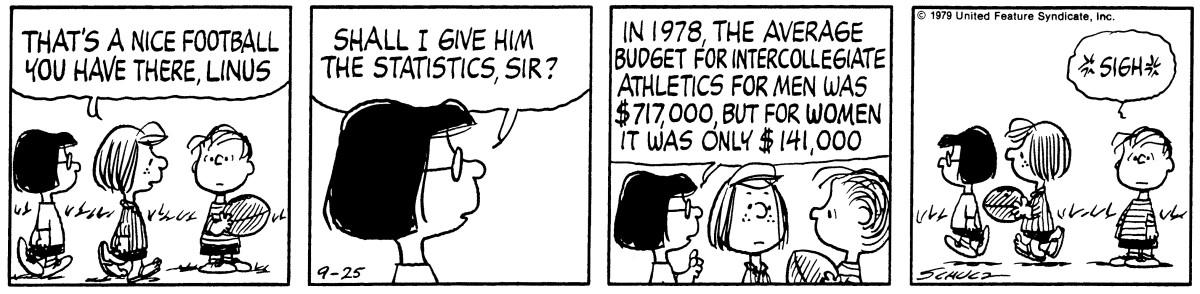

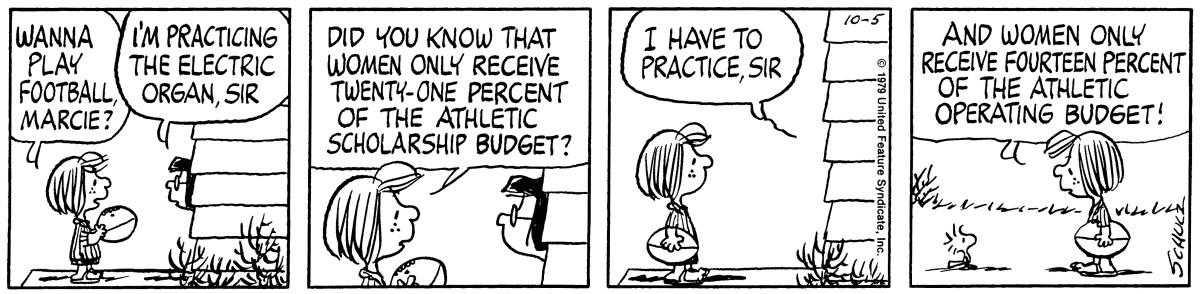

While America debated the federal government’s role in promoting equality for women, Schulz took a stand. For 12 days in the autumn of 1979, he used Peanuts to push for gender equity in sports.

During this story arc, which ran from Sept. 24 to Oct. 6 (excluding Sundays), Peppermint Patty temporarily stops being a terrible student and instead becomes a fierce, informed advocate for Title IX. She calls out the NCAA for the gender-based imbalance of funding for collegiate sports. She laments that women have “been silent for seventy years about the unfair treatment of women athletes,” but she posits that this inequality is “causing an uproar.” Schulz leaves room for optimism: “I think the day is coming when women will achieve equality in sports,” Peppermint Patty tells Marcie.

For Jeannie Schulz, Sparky’s second wife and widow, Charles Schulz’s genius was his ability to take real emotion or a real situation and craft it into one humorous comic after another. And that’s exactly what he did with Title IX.

“He didn’t want the strip just to be a gag a day. He wanted to present something that was real, either real emotions, or real facts,” she says. “And it’s trying to make real facts funny that is what made him a giant among cartoonists.”

This comic strip activism was revolutionary. Millions of Peanuts readers around the world were exposed to the research and talking points of the Women’s Sports Foundation, where Schulz had obtained the information he used in the storyline.

“It was wonderful. The message of women’s sports—the message that it’s OK for girls to be involved in sports. Not only OK, but fair!” Eva Auchincloss, the director of the Women’s Sports Foundation at the time, says. “And I think fairness is what motivated him to. It was only fair.”

While Peppermint Patty’s explicit advocacy was the most obvious indication of Schulz’s convictions, his passion for women’s sports wasn’t limited to just 12 days. Peanuts routinely references female athletes, notably King and Peggy Fleming. Other female characters, such as Lucy, also play sports, and games are never segregated by gender. And Peppermint Patty’s presence as not just an athlete, but the athlete—the best athlete—in the strip makes her even more remarkable.

Growing up, even Billie Jean King could be deferential to men on the tennis court. As a teenager, she practiced with boys, and naturally she’d often win. When she came off the court, people would always ask whether she had won—and whether or not she did, she’d always say her male opponent won. Relieved, he’d thank her for saving him from inevitable derision.

“I like the fact that [Peppermint Patty] spoke up. I like the fact that she didn’t hold back on the field in sports,” King says. “Because a lot of girls would dumb down a lot, so the guys always win.”

Adds Siegal: “She was the best and everyone knew it. And everyone accepted it.”

The final strip of Peanuts ran on Feb. 13, 2000, the day after Charles Schulz died of colon cancer. Schulz’s first published strip—Li’l Folks, the predecessor to Peanuts—launched in 1947, in a world that didn’t believe women belonged on the sports field. His last work came the year after the U.S. women’s national team won the World Cup. It came two years after Pat Summitt’s Tennessee Lady Volunteers won their third straight national basketball championship. And it came months after a promising young tennis player named Serena Williams won her first major title.

From December 2011 to August 2012, the Charles Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, Calif., produced a special exhibition called “Leveling The Playing Field,” which celebrated 40 years of Title IX and honored Schulz's commitment to women’s sports. The Women’s Sports Foundation calculated in 2012 that female participation in college athletics had grown by a staggering 560% and female participation in high school athletics had skyrocketed by 990% since Title IX became law.

But Schulz’s dream of gender equality in sports hasn’t yet been realized. The U.S. women’s national soccer team, now a three-time World Cup winner, is battling the U.S. Soccer Federation for equal pay—and that followed a legal dispute with FIFA over artificial turf fields at the 2015 Women’s World Cup. Several women’s professional leagues, like the National Women’s Soccer League and National Women’s Hockey League, are struggling financially, unable to draw the media attention given to men’s sports. Even tennis, which has greater gender equality than any other sport, is facing renewed debate over pay equity.

Behind the scenes on an NWHL road trip with the Riveters

For King, Schulz’s longtime friend, the pervasiveness of sexism and inequality on the field should inspire women to continue to demand better treatment—like Peppermint Patty did.

“It’s OK to ask for the cake and the icing and the cherry on top. We’re supposed to be so grateful for the crumbs, OK? ‘You ungrateful girl, you’re doing better,’” King says. “We’re doing better? Better doesn’t mean it’s right!”

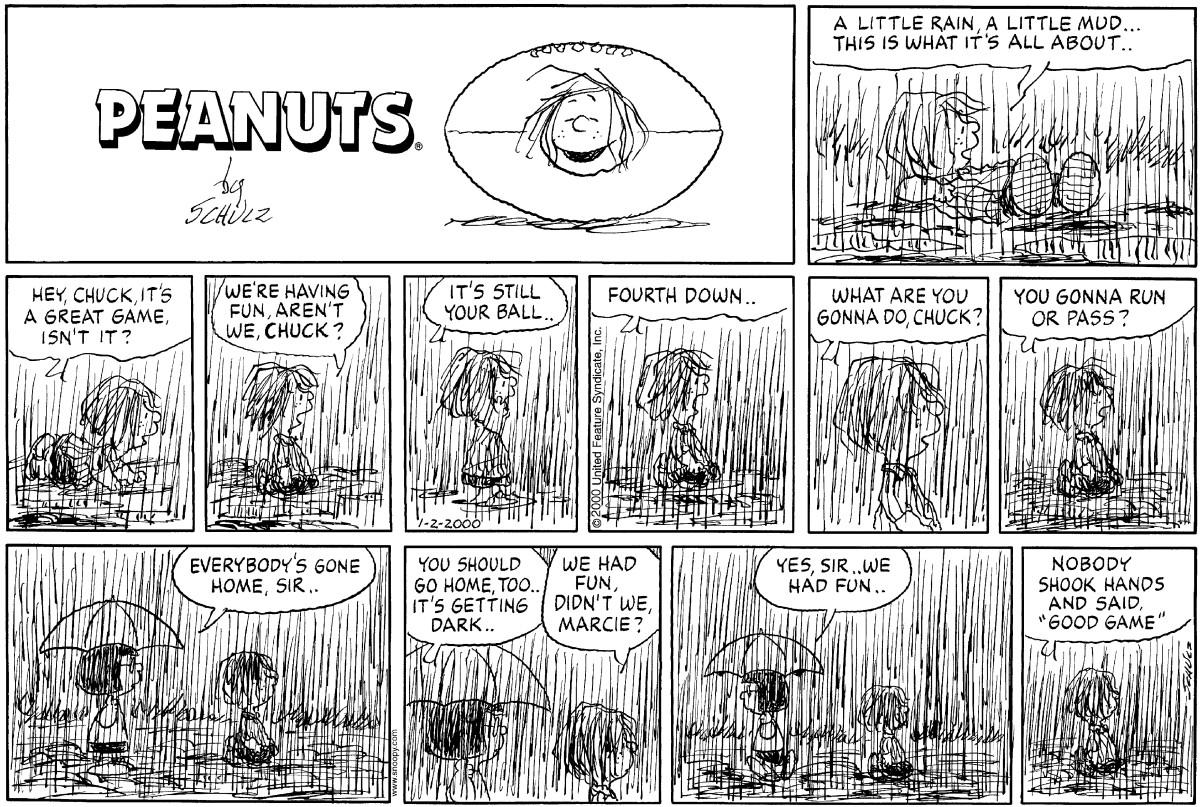

In this critical moment for women’s sports, Peppermint Patty’s unapologetic stand for equality hasn’t lost significance. Her final Peanuts appearance came on Jan. 2, 2000, in the last weeks of Charles Schulz’s life. As torrential rain drenches the football field, a soaked Peppermint Patty calls out to Charlie Brown. But neither he, nor anyone else, appears to be present.

Nothing could force her to leave the field.