Gatorade Athlete of the Year MacKenzie Gore enjoyed a baseball season of near perfection

MacKenzie Gore thought he could be great, but he did not know for sure. There was considerable hype surrounding the lefthander in tiny Whiteville, N.C., but Gore hadn’t spent much time facing the country’s top competition. He had delayed the start of serious travel ball by a year to stay in the legion league with his friends. He rarely got a look at a radar gun. To manage his workload, he didn’t pick up a baseball for months during the off-season and as a result, he’d thrown hundreds, if not thousands, of fewer pitches than most top players his age.

So the 2016 Perfect Game All-American Classic, held last summer at San Diego’s Petco Park, offered him a chance to find out how close he was to his goal of being the best amateur player in the country. In the fifth inning the Whiteville High rising senior took the mound, poised to mow down a collection of top hitting prospects. He went into his pretzel-like windup, right knee to his left armpit, right toes nearly in line with his hands . . . and then labored through a 39‑pitch frame, surrendering two walks and a couple of runs.

Man, he realized as he trudged to the dugout. I’m not even the best player on the field today.

Gore had always been diligent, never missing a workout and practicing his delivery in his bedroom mirror each night. His coaches encouraged him to first learn finesse and control, promising he would add velocity as he matured. After the Petco outing Gore decided to accelerate the process. So—cue the Rocky montage—he added a daily weightlifting session, focusing on his lower body, and packed an extra 15 pounds onto his then 6' 1", 170-pound frame. He refined his delivery. He grew an inch.

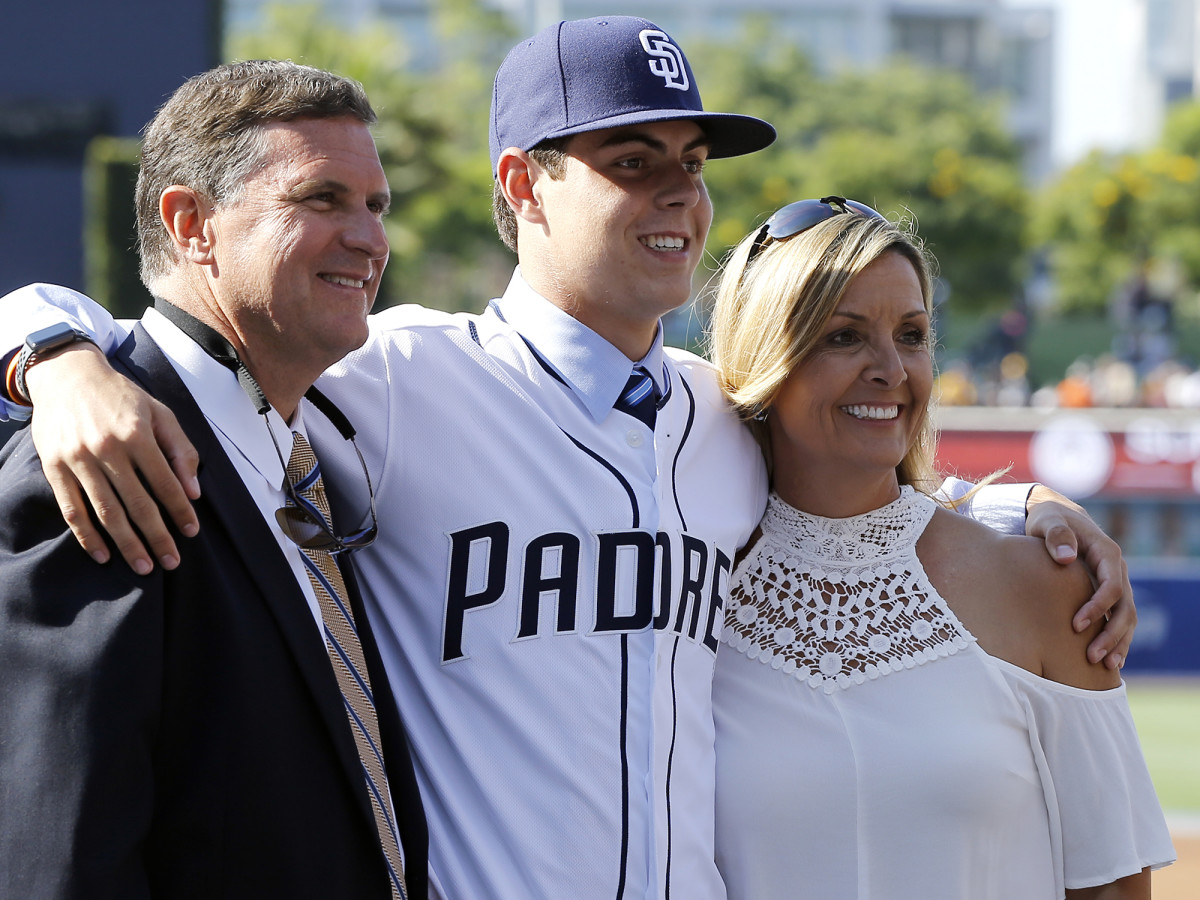

Today he is the Gatorade High School Athlete of the Year, the Baseball America high school player of the year and the No. 3 pick in the 2017 MLB draft. He’s collected so many awards that he’s started sharing them with his teammates. Though he asked to be excluded from consideration for a third state championship MVP in four years, Gore earned the plaque, posed with it, then handed it to the freshman who’d delivered the title-winning hit.

His statistics this season approached perfection: Gore allowed just two earned runs (in 74 1⁄3 innings) for an ERA of 0.19, whiffed hitters at a rate of 14.89 per seven innings and had as many walks (five) as complete games. Says Whiteville High coach Brett Harwood, “He’d strike out 13 and we’d say, Aw, he didn’t have his best stuff today.”

Gore also played first base and the outfield well enough, scouts say, to have gone in the third or fourth round as a position player. He once hit a ball so hard that the opposing rightfielder, without taking a step, turned and waved goodbye as it sailed over the fence.

But Gore’s future is on the mound. His fastball sits between 92 and 95 mph; it has touched 97. He also mixes in a curve, slider, and changeup. Last month the Padres signed him for $6.7 million, the largest bonus in franchise history. San Diego will start recouping its money before Gore ever throws a pitch for the Padres: Whiteville’s two sporting goods stores immediately placed orders for Padres gear to display alongside their Braves merchandise.

* * *

Thirty years ago tobacco plants seemed to stretch from downtown Whiteville (pop. 5,601) to the horizon. But as the industry declined, the town did, too; farmers struggled to make do with corn, soybeans and sweet potatoes, while their children left for nearby Wilmington or Raleigh. Civic pride is especially meaningful in a place like this, where nearly everyone knows MacKenzie Gore from church or from seeing him stocking shelves at McNeill’s Pharmacy.

The town ground to a halt this spring whenever Gore took the mound. Harwood fielded so many questions about scheduling that he finally declared that Gore would just pitch every Tuesday. The local youth leagues cancelled their games the day of his last home start, and school let out at 11:30 a.m. on the opener of the state tournament—the baseball and softball teams both qualified—so fans could beat the traffic on the drive to Raleigh. An enterprising burglar could have made a fortune by checking the playoff schedule; Gore’s postseason starts drew nearly 20% of the town.

The Gatorade High School Players of the Year who never became household names

Pint-sized Whiteville pitchers with exaggerated leg kicks are on the rise. Even Gore’s mother, Selena, uses MacKenzie as a model, telling her fifth-grade students, “You have to do your homework before you play. MacKenzie does his.” Gore signed autographs after outings for clusters of wide-eyed local elementary-schoolers—and then, at road playoff games, for kids in opposing team colors.

It would be tempting to say that he sees himself in them, but when he was their age, MacKenzie couldn’t have been less interested in baseball. T-ball had bored him in preschool, and at age eight he insisted he wanted to play soccer. All your friends are playing baseball this year, his parents cajoled. You’re going to be lonely. If you hate it, you can quit.

Fine, MacKenzie agreed. I’ll play if I can quit. That was the last time they heard that word. Selena and her husband, Evan, knew their boy had found a home on the mound, at 11. He threw a strike—and stopped to clap for himself.

Since then the applause has come from others. Even in the community Sport magazine dubbed Baseball Town USA in the 1980s amid a string of state championships and first-round draft picks, no one had seen anything like the commotion surrounding Gore. He worked in obscurity early in high school because he had eschewed the showcase circuit, but after he no-hit the top seed in the playoffs as a freshman, the seats behind home plate began to fill with college coaches. He met with UNC, Clemson and Virginia, but signed with East Carolina the summer after his sophomore year.

The circus got bigger as scouts began paying attention before teams with later picks realized they were wasting their time. The Gores’ home phone rang nonstop. In an attempt to keep dinnertime sacred for MacKenzie and his sisters, Meredith and Lexie, the family relocated the traditional home visits to Harwood’s office during MacKenzie’s lunch period.

To outsiders Gore’s unruffled demeanor was surprising: He was a rock star, the unquestioned leader of a team on which he was not only the best player but also the only senior, and a young man whose future rested on his ability to perform at his peak while a hundred adults studied him for flaws. Yet his main concern was that if he missed his midnight curfew, he would lose car privileges. “Part of what makes him great,” says Hammond, “is handling the mental part.”

East Carolina coach Cliff Godwin, in a phrase borrowed from Bill Belichick, tells his players to “ignore the noise.” No one heeded that more than Gore. (After yet another 97‑mph heater, the coach would text Gore: “MacKenzie, you need to back off that a little bit if you’re going to come to East Carolina!”) Godwin checked in regularly about Gore’s outings and the scouting attention and was unsurprised when, after a mock draft placed the lefty in the top 10, Gore shrugged. “They’re not the ones picking,” he said of the analysts.

Gore and Padres agree to $6.7 million signing bonus

When the Wolfpack lost in the Class 1A finals his junior year, Gore blamed himself for the team not having the right mix of calm and intensity and vowed to remember that his teammates were studying him for cues. Early in his senior season, while Hammond’s heart raced as his ace warmed up in front of scouts, Gore just grinned. “This is fun,” he said.

That attitude has already helped him adapt to life in Phoenix, where he joined his rookie-level team. Aside from the new coaches and more advanced hitters, Gore will also have to adjust to the relative anonymity of minor league life. If he ever misses being a celebrity, he can check in with the citizens of Whiteville. “They’ll probably give him the key to the city soon,” says Godwin. “If he has the career we expect, they’ll probably name the town after him.”

Gore’s goal is simpler. Next time he takes the mound at Petco Park, he wants to pitch well enough to make that last inning a distant memory.