Life After Escaping the World of Human Trafficking

Deshae Wise is running. Her wavy, black shoulder-length hair flows behind her as she blurs across the Edwards Stadium track at the University of California in Berkeley. To keep her focus, the 18-year-old fixes her eyes on a single point, locking in just before she takes off: to the east, the shrubbery atop Strawberry Canyon; or, to the west, the Golden Gate Bridge, glimmering in the distance.

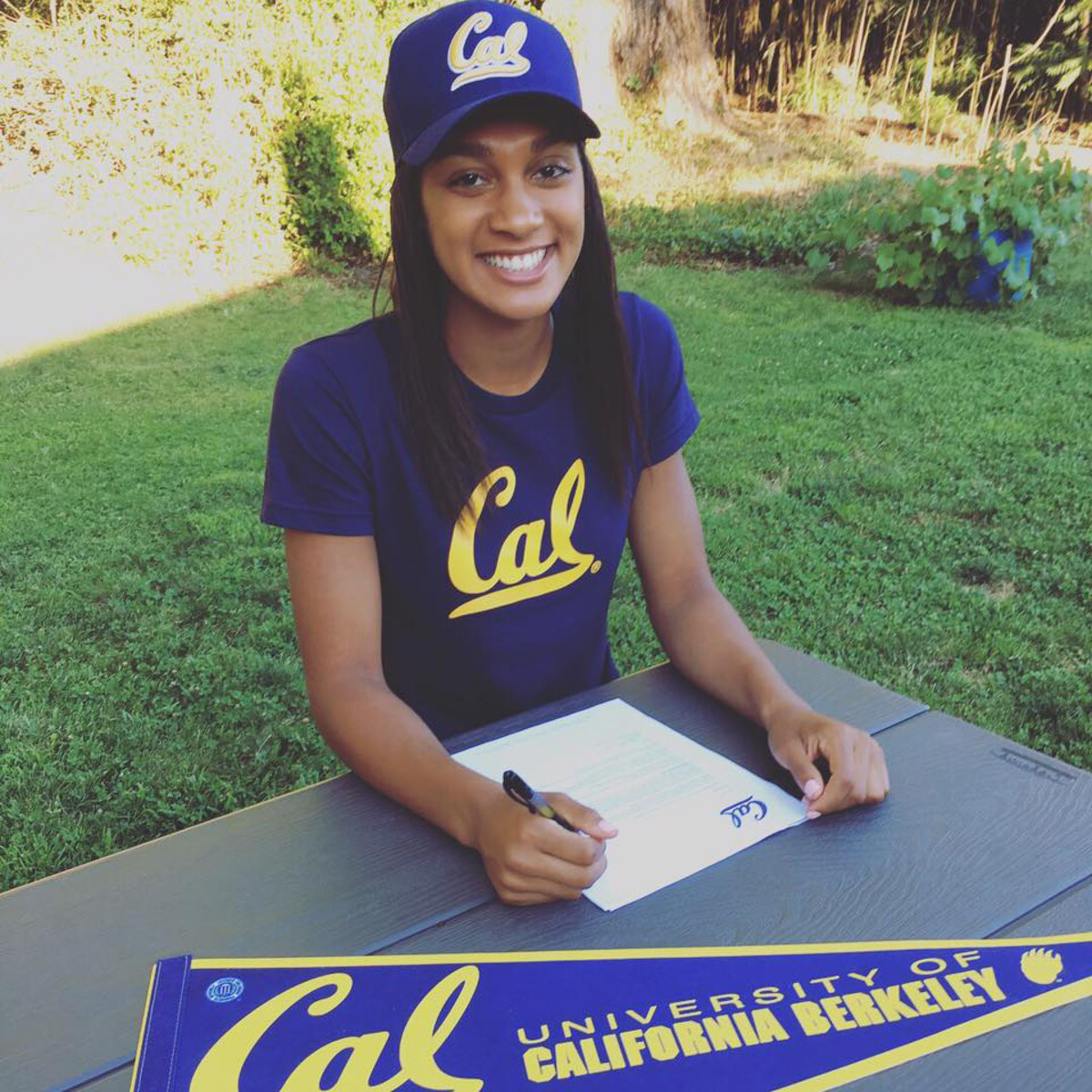

A freshman on the Golden Bears’ track team, Deshae is one of the best young runners in the country, a Gatorade Athlete of the Year as a high schooler in Oregon, where she was the 2017 state champion in the 100- and 300-meter hurdles and 100-meter dash. In just her second collegiate race, at the Husky Classic in February, she ran the preliminaries of the 60-meter hurdles in 8.84 seconds, the eighth-fastest time in school history; in the final, she ran an 8.71, tied for fourth-best.

Superhuman speed aside, she is, on the surface, not so different from many of the other students on a campus littered with well-rounded overachievers. She arrived last fall from Grants Pass (Ore.) High with a 3.7 GPA. She speaks Mandarin, plays piano by ear and likes to draw. In her first eight months on campus she has joined the black business association and volunteered with Habitat for Humanity, all while upping that GPA to a 4.0. Next year, she’ll be a resident advisor in the dorms.

Few, though, have come as far as Deshae, and not just because she hails from a country hamlet tucked away between the edges of the Umpqua and the Rogue River-Siskiyou national forests. Just 11 years ago, Deshae Wise was living in captivity with her mother, fighting always for survival. Looking back today, she can point to countless moments from her childhood that no human should ever endure. Like the time she came back from a weekend away and found her mother severely injured, face broken in five places. Or the time when she was seven and she found herself fleeing her mother’s pimp, scaling fences in the middle of the night.

Growing up, Deshae knew only that she and her mother, Rebecca, seemed always to be running. Why or from what, it was never perfectly clear to the young child. But then, finally, when Deshae was 12, Rebecca decided to explain it all. Pulling her car into a driveway, Deshae in the front seat, Rebecca’s story poured out, every word a bit of relief off her chest. But as the details poured out Deshae began to sob. Why would you stay? Why wouldn’t you leave for me?

Slowly, Deshae would come to learn the full story, to understand the difficulties of leaving. She would begin to grasp not only the depths of her mother’s pain, but also the burning desire to live free. To run.

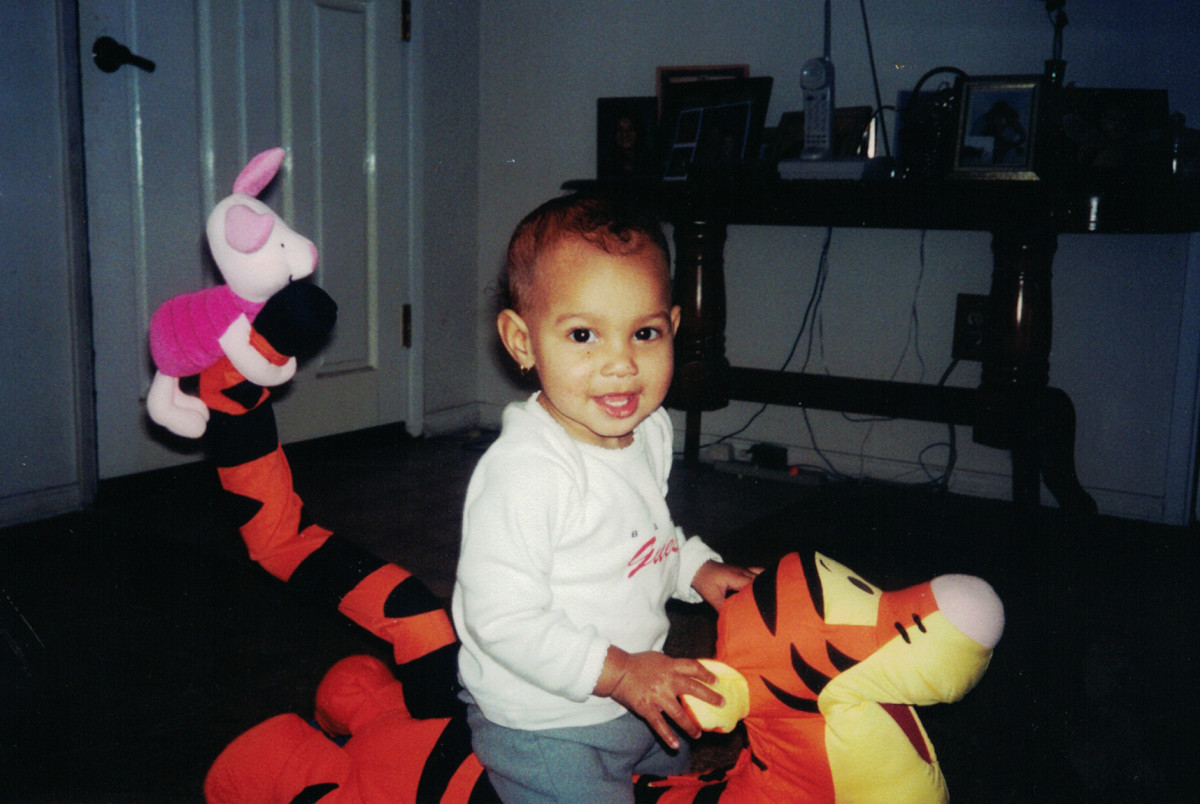

Rebecca Saffer was the girl with the kid. She’d holed up with one-year-old Deshae, all scraggly mess of hair and big brown eyes, and some friends in Eugene, near the University of Oregon campus. This was 2000, and Rebecca, then 18, made herself a part of the campus scene, even though she wasn’t enrolled: she lived with friends and attended Ducks basketball games with Deshae dressed in a tiny cheerleader outfit.

Deshae was the product of a relationship Rebecca had in Maryland, where she had worked as a waitress and crashed with a cousin; now Mom was back near her hometown, two hours away from Eugene, and she was hoping to gain a bit of the college experience. That and she was looking for someone to complete her family of two.

Khaled, who Rebecca first met at a campus restaurant, was supposed to be that final piece. Handsome and charismatic, he was the kind of guy all the girls gravitated toward, and here he was taking a special interest in Deshae, bringing her to the park and to Chuck E. Cheese’s. When Khaled (not his real name) invited Rebecca to move to Las Vegas with him after just six months, she saw it as the start of a new future. They would get married and buy that dream house with the white picket fence.

But the dream ended before it even began, according to Rebecca, whose recollection of the next several years is backed by FBI statements and court records, public documents and interviews. Less than 24 hours after arriving in Vegas, she says, things quickly turned. Khaled told Rebecca he wanted to take her out on the town. “Get dressed up,” she remembers him saying.

Deshae stayed with Khaled’s brother, but instead of heading to the strip, Khaled drove him and Rebecca to a dead-end street anchored by a deserted strip mall. Rebecca remembers just darkness and the hum of the car. Khaled, she says, turned to her and explained with a seriousness on his face: He needed money for the apartment, for Deshae’s food. . . . And Rebecca had to pay him. Now.

Khaled, she says, pointed to a door with a security camera above it and told her to enter. Inside she found a smoke-filled room with three desks pushed next to one another, a woman seated behind each. Behind them, written out cleanly on a dry-erase board, were the words brunette, blonde, asian, redhead. . . . It was all too clear, too real. She was at an escort service, and Khaled expected her to sign herself up. No way. She was shocked, confused, and terrified.

Back in the car, Khaled slapped her across the face. Rebecca was suddenly terrified. She was in a new city. . . she didn’t know her address yet. . . and she didn’t know where her daughter was. The rest unfolded in a blur of fear and confusion. At some point there was a phone call from a “local” in the Green Valley area, 15 minutes away. Khaled drove to a townhouse, dropped Rebecca off and parked nearby.

Rebecca knocked on the door and was greeted, to her surprise, by an attractive male in his 20s—she remembers him looking like a grown-up high school quarterback, with wavy black hair. Inside, she started reluctantly to mime a lap dance, but after a few minutes the man grew frustrated. He grabbed Rebecca by the waist, pulled her skirt up and, without her consent, had sex with her.

Rebecca froze. Before she knew it, she was walking out the door, adjusting her skirt.

Back in the car, she remembers Khaled asking, “How much did we make?” Three hundred-twenty dollars. “You’ll do better next time,” he said. And then: “You didn’t have sex for this, right?” Ashamed, Rebecca shook her head. No. She looked out the window and cried.

Back at the apartment they shared, Rebecca found her daughter safe and sound. But still: She was alone in Vegas. She clung desperately, naïvely to the hope that she would repay Khaled and then. . . . maybe they’d be back on track. But that never happened. Instead, Rebecca became a victim of human trafficking, coerced into prostitution.

Khaled was what those in his world call a “Romeo,” a trafficker who uses romance to woo unsuspecting girls (as opposed to a “gorilla,” who employs brute force). But now that he had his hooks in, he threatened Rebecca nightly: If you don’t make your quota, you’re going to find your daughter alone on a corner. The way Rebecca saw it, she was trapped. She says Khaled provided her with cocaine. (She’d used a few times before, but now she had an enabler.) She got high as a coping mechanism and to mask her shame; the drug offered a numbing effect so she could prostitute. . . so she could make money. . . so she could keep her daughter. Khaled had control. Escape seemed impossible.

In some ways Deshae’s childhood felt not so different from the norm. Mother and daughter would spend days at a local park and at the pool in their apartment complex. At night, while her mom was physically forced into prostitution, Deshae would often stay with Khaled’s brother or at a 24-hour day care—but even that was common in Vegas, where parents tend to work odd hours.

Eventually, though, Rebecca’s experience began to affect everyday life. “You’re going to come to my sing-songs, right?” four-year-old Deshae would ask her mom before a preschool recital. On the night before the after-school performance, Rebecca was on a cocaine binge, waking later to 20 frantic missed calls.

After nearly two years in 2004, Khaled traded Rebecca to another Las Vegas trafficker (in exchange for clothes and jewelry, and maybe money—Rebecca says she isn’t sure). Mother and daughter joined three other women in a mini mansion owned by a man named Kevin. The house was opulent, with dual marble staircases, a custom pool and travertine running from the beginning of the driveway to the outside of the house, leading up to and covering the first-floor windows. “We’re a travertine-type family,” Kevin (not his real name) would say.

Deshae, who was five when they arrived, was enrolled in an expensive private school. She called the other women in the house her “aunties” and befriended a young boy who lived in the house. They were all close.

But while Khaled had been more manipulative, Kevin was paranoid. Strictures were put in place. Kevin was obsessed with secrecy, paranoid of his operation being raided. In a gaudy neighborhood, Deshae and Rebecca’s new prison easily fit in—save for one detail. Most residences had a glass oval insert in the front door. The front door at Kevin’s was solid. There was no way to see in.

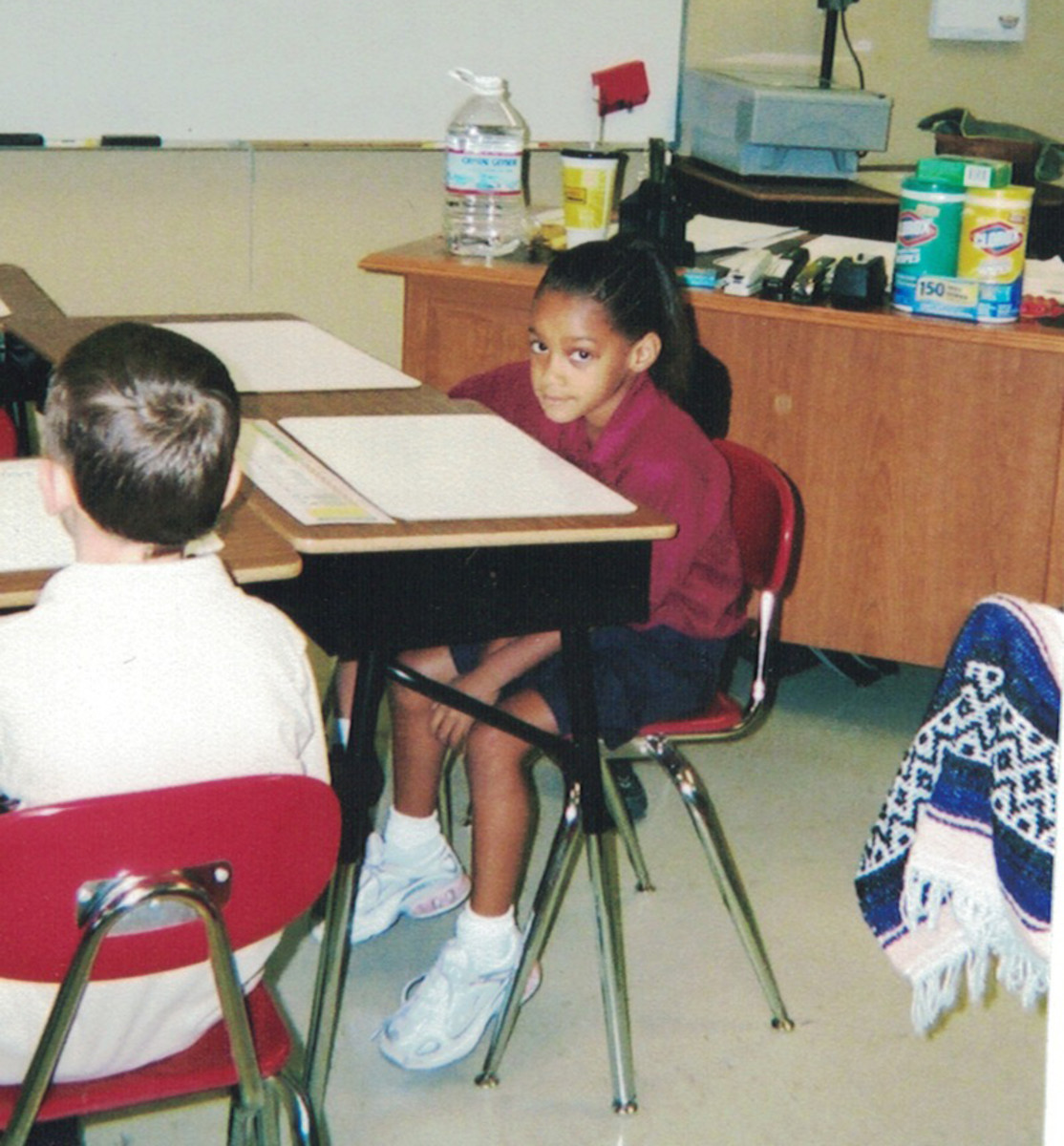

By the time Deshae reached kindergarten, looking back, it’s clear that something was amiss in the little girl’s life. A picture of her classroom that year shows Deshae alone, slumped on her desk, in a red sweatshirt, black shorts and with white sneakers—looking forlorn. At home, she knew she didn’t have a normal family. “Kevin did fatherly things with me,” she says. “But I never felt like I had a loving connection. I don’t remember feeling that I really love this guy.” And even if she had any friends, they were banned from visiting the house.

As Deshae grew older, Kevin grew worried. The girl was mature enough to tell someone—a teacher, a coach, a classmate—what was going on at his home. She could tell them about the time a TV stand fell on her leg, and how she screamed for help but no one came—they were sleeping in from being sold around until dawn. Or about the time she did a walking handstand and Kevin rewarded her with a $100 bill. Even she knew that was odd. Or the time her mom scooped her up, turned on the TV and told her to stay in her room until the punching stopped.

Even as Deshae’s suspicions grew, though, she stayed quiet. “I remember my mom telling me good night, and she would be leaving when I would be going to bed,” Deshae recalls. “She would be dressed up really nice. I just assumed she worked at a fast-food restaurant. I didn’t know what else she could be doing. I just assumed.”

The reality was far darker. Rebecca says Kevin started to beat her soon after she arrived. He would grab her by the neck and scream, “B----, you don’t mess with me. I’m not one of those punk motherf------ you’re going to talk to anyway you want.” He would shove her head into the wall, throw a chair at her, punch her in the stomach, she says.

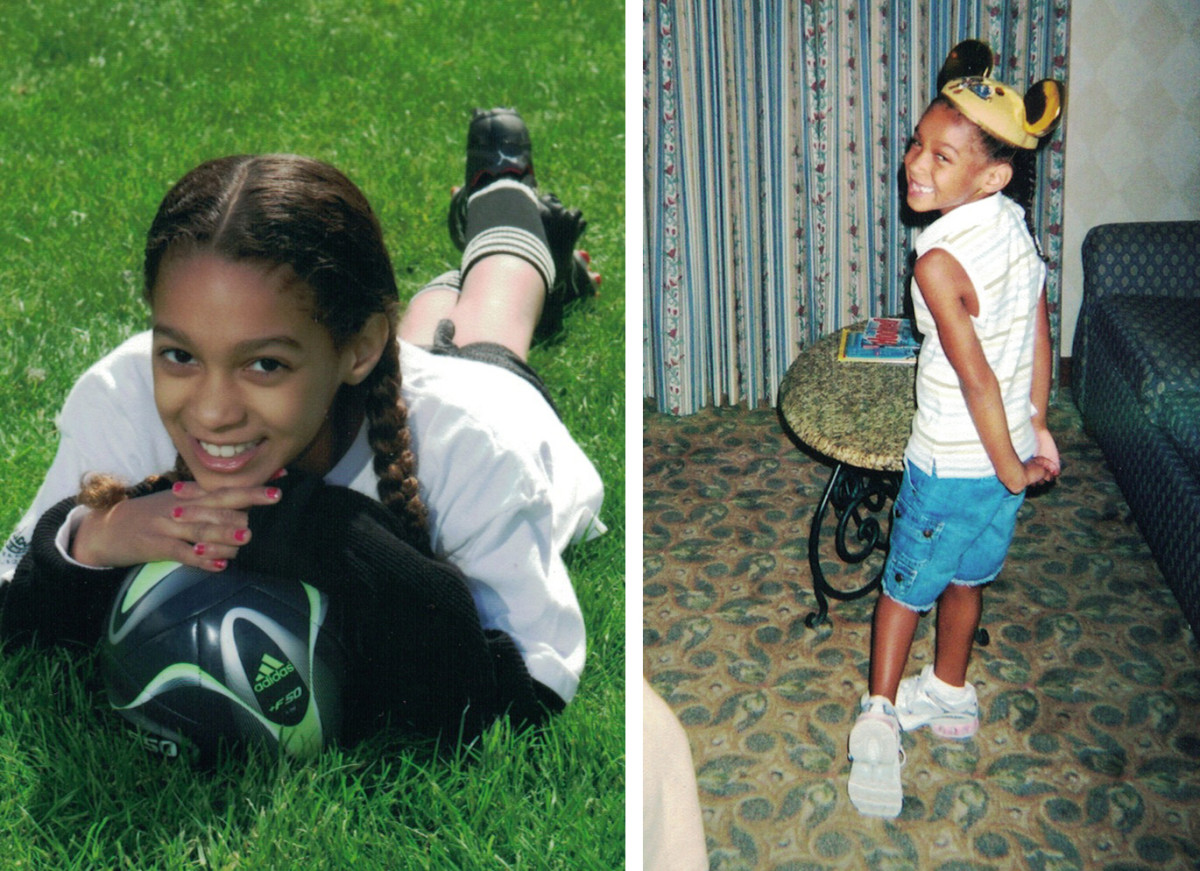

Through it all, Deshae carried on. After all, some things were O.K. She played a flower in a school production of Alice in Wonderland. She patrolled the soccer field wearing pigtails, red nail polish and a smile. In fact, she was blazing fast, blowing by defenders. By the time she reached middle school she was excelling, too, at volleyball and basketball. Parents would gush to Rebecca. She has a gift, they said. She could run.

It was time to run.

By the time Deshae was eight, Rebecca had tried to flee with her daughter four times. Once, they made it back to Rebecca’s mom’s house in Grants Pass, but Kevin tracked them down in Oregon and brought them back to Vegas. Another time, feds surrounded one of Kevin’s houses in Vegas in the middle of the night as part of a tax-evasion investigation, and Rebecca took Deshae out the back door and climbed over a fence into a neighbor’s yard.

If that seems like the perfect opportunity to escape, Rebecca didn’t see it that way; she didn’t see any choice but to stay with Kevin—a common sentiment among victims of trafficking. “There’s the realistic stuff, like: How would I get a job? Or what is society going to think of me?” says Elizabeth Hopper, a clinical psychologist and the director of Project REACH, which helps trafficking victims. “Traffickers control the living space, the money, where to go. . . . And then: Is he going to come after me?”

It would take outside intervention to free Rebecca of Kevin’s grips. With federal officials bearing down, Kevin turned himself in on charges of tax evasion. On Nov. 19, 2007, he signed a factual statement confessing to one count of tax evasion. He was sentenced to 24 months in jail, with three years supervised release. According to the charging document, Kevin laundered the women’s earnings—as much as $18,000 a month—through various bank accounts before spending the bulk of it on Rolls Royces, horses and multiple houses across Texas and Vegas. Ultimately, he was never charged with human trafficking, which carries a much stiffer sentence of up to 20 years. Before he started his sentence Kevin flew to California to visit his mother, and as soon as his flight took off Rebecca and Deshae made their break, packing two suitcases as quickly as they could. Even then, freedom was not so simple: All of the credit cards Rebecca used were tied to Kevin (and in the years after 9/11, purchasing airfare in cash was nearly impossible), so she had to arrange for a relative to procure two tickets.

Later that day, December 31, 2007, after a two-hour one-way flight, mother and daughter landed in Medford, Ore. Rebecca’s aunt picked them up and drove the refugees 30 miles back to Grants Pass, where they would stay with Rebecca’s mom. Kevin called and called and called, demanding to know where Rebecca was, but she didn’t answer. She knew he would be in jail soon enough. The spell was broken.

For the first time in nearly seven years, Rebecca could breathe. She and Deshae were finally free.

When Deshae looks back, she does not dwell on the darkness. In fact, she considers herself fortunate. “The probability that I wasn’t sexually or emotionally abused is so slim,” she says. “In any other situation, it would have happened to me—but it didn’t. That fact, that my mom is still alive and healthy. . . it makes me very grateful. I’m very inspired by my mom, that she has the strength to share her story and help others learn about the issue and recover. I take pride in sharing my story.”

That story—Deshae’s story—was shielded, for the most part, from the horrors in Vegas. But the effects of those years are evident. Today Deshae yearns to control every situation, which she attributes to her unstable surroundings growing up. For years, she was unable to fall asleep until her room was perfectly clean; she’s sure now that this has to do with seeing Kevin physically punish her mother if the labels in the pantry were left facing the wrong way. Deshae has also worked on rekindling her relationship with her biological father, Keith Wise.

Rebecca, for her part, is using her experiences to lead the fight against human trafficking. While there are few comprehensive statistics on the subject in the U.S., the Polaris Project, a non-profit, received 178,971 hotline alerts regarding instances of human trafficking between 2007 and ’17. Leave these borders and it gets more grim: The International Labour Organization estimates that 20.9 million people worldwide work in trafficked labor. In ’14, Rebecca started a non-profit, the Rebecca Bender Initiative, that helps survivors and works to combat future trafficking by educating law enforcement officials. She wrote a self-help book for survivors, Road to Redemption, and she speaks at universities, community groups and academic conferences. In ’09 she married Matthew Bender, a contractor whom she met at church, and together they’ve since had three children. Life is good, but Rebecca lives each day believing that Khaled and Kevin are free and still operating in the trafficking world. (Rebecca requested that aliases be used in this story, for fear of reprisal. SI did not reach out to Khaled or Kevin, at Rebecca’s request, to avoid retaliation. Their identities—and Rebecca’s story—were confirmed through court records and other public documents, and through interviews with the FBI agent on Kevin’s case and, in Kevin’s case, one of the other women in the house.)

Through her foundation work, Rebecca is exposed to a spectrum of survival stories—those who end up addicted to drugs, those who end up being trafficked again, those who somehow bounce back and prosper. In Deshae’s case, Rebecca was her shield. “[Deshae] had a sense that the world isn’t safe, but that there are safe people,” says Dan Sartor, a clinical psychologist who specializes in trauma and who is familiar with Rebecca and Deshae’s story. “If you have a protective individual who can be a buffer, it can matter a lot.” Rebecca’s efforts to shield Deshae from the worst helped her to thrive once they escaped. There are plenty of recovery stories, but, Sartor says, it’s pretty rare for someone to recover as well and as far as Rebecca and Deshae have.

Deshae began running competitively in the eighth grade, late for most athletes but in what can be considered the dawn of this particular athlete’s second life. She won three state titles at Grants Pass High and her time of 13.96 seconds in the 100-meter hurdles at the 2017 Class 6A championship was second-best in the history of a state known for track and field, inspiring The Oregonian to call her “one of the all-time greats.” That got the attention of Cal (and Oregon State and Idaho and Cal Poly, each of which offered a scholarship; Oregon said she could walk on), for whom her career got off to a fast start this winter. She ran a 25.38 200 in her college debut, in January, her first time running indoors, good for 20th out of 103 runners. A month later, at that Husky Classic, she began scaling Cal’s all-time list.

Deshae’s composure off the track, though, is something more remarkable. Asked to share her story, she recounts even the most traumatic details matter-of-factly. She doesn’t flinch. Early on, she says, she blamed herself for Las Vegas; her mother stuck around so long, she rationalized, to keep her daughter happy. Later, as she got older, as she learned her mother’s story and the truth about her childhood, she began to use it all as fuel. “A fire started in me to beat the odds even further,” she once wrote in a school essay.

As she plots the road ahead, Deshae plans on majoring in business, maybe getting into public policy, promoting social welfare (she’s recently taken an interest in prison reform), “making a difference in the lives of other disenfranchised people.” Anything to help, she says.

Berkeley can feel like a long way from Grants Pass, with a student enrollment surpassing her hometown’s population. “It may be overwhelming at times,” she says, “but my senior quote [in high school] was: Embracing the journey. I finished fourth in state my freshman year, second my sophomore year, constantly getting better—that’s my philosophy. I’ll do the best I can and grow with life, see where it takes me.”

On a wall of her room back in Grants Pass, Deshae has slapped up a slew of Post-It notes, and written on a red one next to a cup of pens—amidst the Bible verses and reminders to herself—is a simple summation of her life so far. It speaks to where she and her mother have been, and where they are now. It is their life in the neat, script handwriting of a teenager who has already seen too much. On it, she wrote: against all odds, I will shine.

To learn more about human trafficking in America, and to get involved, please visit: The Rebecca Bender Initiative, The National Human Trafficking Hotline, Shared Hope International or The Epik Project.