More Than Five Decades After Lisa Lane's Success, Equality Still Eludes Women in Chess

In 1972, Bobby Fischer made his third appearance on The Dick Cavett Show. He was at the peak of his fame; the show was taped shortly before he was crowned world chess champion and aired just after. The audience seemed just as wild for him as for the episode’s other guest, Mick Jagger. (“You brought a fan club with you,” Cavett quipped.) American chess was more popular than ever—before or since—and it was hard to tell who was more of a rock star.

In Cavett’s monologue, he wondered about women’s chess: specifically, why there wasn’t more of it. “There’s only one woman’s player whose name I know,” said the late night host. “That’s Lisa Lane, and the only thing I recall about her is that she’s dead.” The subject came up in Cavett’s conversation with Fischer. Asked if he thought that chess was sexist, Fischer replied, “I don’t think it is at all. I’d welcome some girls in chess.” Did he know any girls who’d tried? “Well, there was Lisa Lane. By the way, I think you said she was dead? She’s around.”

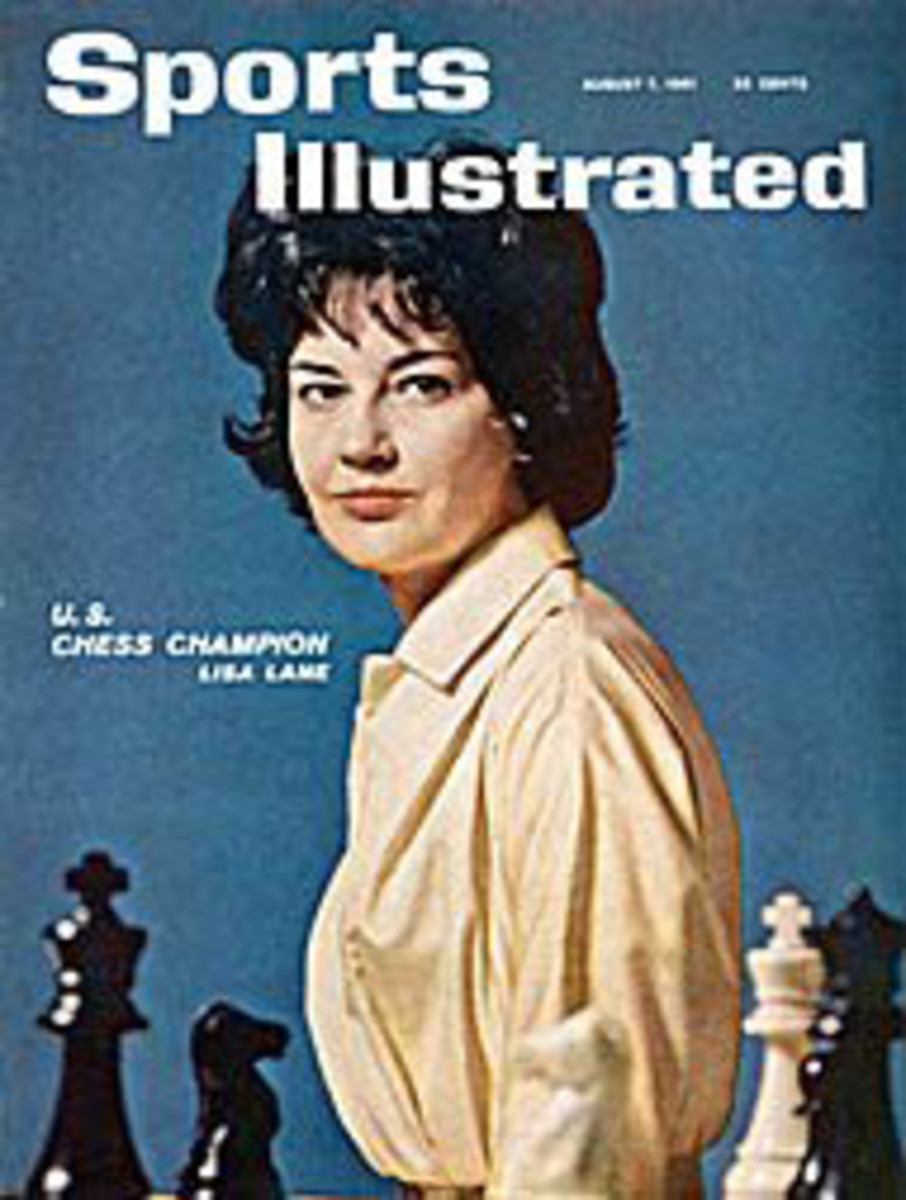

Cavett apologized. Fischer was right: Lisa Lane was around. Yet Cavett’s flub was, in a sense, understandable. Lane had spent several years as the women’s national champion, but, more than that, she’d been one of the most compelling chess stars of the ‘60s. She became the first chess player on the cover of Sports Illustrated. (Fischer followed, a decade later, as the second and the last.) National media wrote about how she played “like a man” and trash-talked opponents to match; they luxuriated in details about her personal life, particularly her love life. And then, suddenly, while reigning as women’s national champion, she quit. She left New York City, where she’d been part of the country’s most vibrant chess scene, and stopped playing in competition. By 1972, she’d been gone from public life for five years.

But she certainly wasn’t dead. She hadn’t fallen out of love with chess, either. Instead, she felt that chess had fallen out of love with her—no longer willing to accommodate a woman who wasn’t interested in matching the game’s narrow standard for an ideal female chess player. She’s still alive today. So is women’s chess, locked in the same fight for equal opportunity.

Through November, chess had a laser focus on two men in London: Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana, battling for the world championship. Norwegian Carlsen had held the title since 2013; American Caruana was the United States’ first challenger since Fischer in 1972. The two played 12 matches, followed by a tiebreaker round after each of the initial dozen ended in a draw. Carlsen, once again, emerged victorious.

But 3,500 miles away, there was another battle of chess elite. The Women’s World Chess Championship was held at the same time—in Western Siberia. The format was different; 64 women played in a frenzied knockout tournament, rather than two men competing head to head. The prize fund was smaller: The female champion, China’s Ju Wenjun, walked away with less than 10% of Carlsen’s haul. And the best woman in the world, China’s Hou Yifan, declined to participate, as she has since 2016, when she announced that she’d no longer play in a system with such a drastically different structure for women.

The World Chess Championship is not, formally, a men’s championship. It used to be—until 1986, when a top female player, Susan Polgar, fought to qualify and had “men’s” removed from the official title. Now, it’s known as the open championship, but the name marked only a small step toward including women. More than three decades later, as the event has cycled through different formats and larger playing fields, only one woman has competed for the championship: Judit Polgar, Susan’s younger sister, who is widely considered the best woman ever to play the game. Her championship appearance was in 2005. Since then, no other woman has even come close.

Hou Yifan is currently the only woman in the world’s top 100; there are seven in the top 500. But women aren’t disproportionately outnumbered just at the top of the leaderboard. They’re disproportionately outnumbered everywhere, from youth competition up. Just 14% of US Chess Federation members are female; that might seem low, but it’s a record high, reached just this year. Most female players consistently find themselves surrounded by men. With a women’s world championship—and women’s national and continental tournaments used to qualify—there’s space for female players to cultivate the game on their own terms and enjoy an elite international environment that would otherwise be inaccessible to many of them.

“People hear about women’s tournaments, and they have this kneejerk defensive reaction—they don’t think it’s good,” says Jennifer Shahade, a two-time winner of the U.S. Women’s Championship and a board member of the World Chess Hall of Fame. “But they don’t realize that women usually play with men. They’re usually playing all in one tournament, and these women’s tournaments are special events organized to promote women in the game.”

That’s precisely why many players and organizers find it crucial to secure a large platform for the women’s championship. In an environment where female players are such a tiny minority, the tournament is an invaluable opportunity to show off talent and grow the game. But that’s hard to do when the women’s championship and open championship take place at the same time, as they did this year. Already working with a smaller profile, the women’s championship had the added hurdle of grabbing attention from Carlsen and Caruana in London for the scores of female players in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia.

“I was surprised when I noticed that it was going to coincide with the world championship,” says 2017 U.S. Women’s Champion Sabina Foisor, one of the country’s two representatives at the women’s world championship. “Because, of course, there are already a lot of eyes on the men. Having the events at the same time—it kind of took a lot of eyes away from the women.”

For those who did watch both, the two championships offered markedly different experiences. The women’s event is structured like March Madness: 64 players, 32, 16, and so on. There’s a key difference in that each pair plays two games, rather than just one, plus a tiebreaker. Otherwise? It has the same drama and upset potential, plus the manic joy of an opening round with a slew of games happening at once. That’s decidedly unlike the taut slow burn of Carlsen-Caruana, which, with its dozen consecutive draws, demonstrated how the open championship’s structure can lend itself to more conservative play—better chess, but not always chess that’s better to watch.

“I personally think that from the fan’s perspective, the women’s championship is more interesting,” says Susan Polgar, who, along with challenging the gender barrier at the open championship, also became the first woman to earn the prestigious title of grandmaster in tournament play. “The women take more risks. They play more dynamically. And they make more mistakes, I’m the first to admit that. But from the fan’s perspective, I think they play more interesting games and they’re more enjoyable.”

However, what’s most exciting for the fans isn’t necessarily most ideal for the players. The open championship previously used knockout elimination, too, from 1998 to 2004. Despite the format’s excitement, many players were frustrated with big upsets and disliked that it was easy for the most deserving player to lose. The men’s criticism was received, and the structure was abandoned. But female players gave similar feedback about the knockout tournament, and for years, there was no response. A change was made in 2010, when knockout elimination became the women’s format only in even years; a 10-game match between the previous winner and a challenger was adopted for odd years. But the fact that knockout elimination was used for any championship could be frustrating—women’s chess was structured primarily to be appealing to fans, while men’s chess was allowed to be as rigorous as desired.

Magnus Carlsen Beats Fabiano Caruana for Chess World Championship

A significant breakthrough finally came in November. The World Chess Federation announced that this women’s championship would be the last of its kind. Beginning in 2019, the women’s championship’s prize fund will increase to half of the world championship’s, and the tournament will switch to a similar structure. But if chess seems like one sport that shouldn’t need a marked gender divide—it’s a work in progress, and it has been for quite some time.

“The day may come that we may not need separate championships,” says Susan Polgar. “That’s the ultimate dream. But I think in order to get there, we need to change society, how they treat women in chess. Slowly, I think it’s possible. But these kinds of changes don’t happen overnight.”

The changes are cultural, financial, optical. They demand reshaping a landscape in which girls and women have been cast as anomalous female islands in an overwhelmingly male game. For decades, chess’ mainstream conversation has featured women as simple parentheticals, rather than subjects of their own sentences; the goal is to build a new framework.

Fifty years ago, though, American women’s chess did have one player who dominated the conversation, however briefly and divisively.

In 1963—a few years after her first national championship, and just before her 25th birthday—Lisa Lane opened a chess club in Greenwich Village, aptly named The Queen’s Pawn. She lived in a little studio apartment above the club. It was open from 2 p.m. to 2 a.m., and she’d play and set up games all afternoon and all night. When she closed up, she’d head out with a crew of her club’s regulars, and they’d decamp to a bar a few blocks over on Sixth Avenue, drinking and talking chess until 4 a.m. or so. Then she’d head back to her studio, sleep until noon, and rise to go downstairs and open the club in time to do it all again. When The New Yorker covered The Queen’s Pawn in 1964, she was described as “the world’s most glamorous chess player.”

She didn’t stand out as her era’s most talented player nor did she finish as the most successful. But Lane was unlike anyone in American women’s chess: a pioneering and polarizing player, unconcerned with public perception, who flamed out amid cultural and financial pressures that are still heavy for many of today’s female players. She quit competitive chess less than a decade after she began; she withdrew from the media that had adored her, and her story faded out. But Lane is inextricably tied to the legacy of American women’s chess—who’s allowed to play, who’s noticed for playing, and who’s able to rise to the top.

“I enjoyed myself immensely,” Lane says now, half a century later. “I had a nice life for a little while there. I was doing what I wanted all the time.”

What she wanted, of course, was chess. Unlike many top players, she didn’t begin as a child. Instead, she discovered the game in her late teen years, after she’d dropped out of high school in her native Philadelphia. Right away, chess consumed her. She began studying obsessively and playing as much as possible, gaining attention in local coffee shops until she was introduced to Attilio Di Camillo, one of the city’s best players. He began coaching her, and he invited her along when he played in the U.S. Championship in New York City in 1957.

SI TV: Can One Kid Return the U.S. to Chess Dominance?

Di Camillo didn’t win. A 14-year-old prodigy, Bobby Fischer, did. On the train home, Lane told Di Camillo how impressed she’d been. Someday, he said, she could have a championship tournament of her own: “If you’re willing to work, you can be the women’s champion in two years.”

He was right. Exactly two years later, in 1959, at the age of 21, she became women’s national champion.

That Lane had been playing for just two years was only one factor that made her championship remarkable. Her background was conspicuously different from that of most top women. They were typically well-educated or from well-to-do families or both. Lane was neither. She’d never known her father. Her mother worked several jobs; Lane and her sister boarded with various families while growing up. She quit high school, and between dropping out and finding chess, she’d held a slew of different jobs, struggling to make something stick.

“I was under a lot of stress—well, we didn’t use terms like stress back then, it wasn’t a psychological era,” she says. “But I had some unhappiness in my life, and chess was a way to get away for a bit. It was an escape, and it was something that I was good at, and it worked. I was able to arrange my life in such a way that I could give it all the time I wanted.

When she began playing, the media had little interest in women’s chess. But Lane motivated them to pay attention. Her story was eye-catching—young, talented, a quick rise to the top—and so, too, were her pictures. Lane was conventionally gorgeous, a point that was considered relevant in news features and match coverage and promotional material. When Sports Illustrated gave her the cover in August 1961, the table of contents described her as “a girl who is not only beautiful but a chess champion as well.” Before the story addressed how she played, it described how she looked: “…she seems a very serious young woman, but beautifully serious, or seriously beautiful, a side of feminine loveliness that Hollywood has rather neglected.”

Lane didn’t particularly care. Her chess was her priority; how people perceived it, or her, simply didn’t matter.

“It didn’t bother me,” she says. “It wasn’t like they said I was beautiful and not a good chess player… I wasn’t a deep thinker about anything but chess in those days. I didn’t really think about the connection between my looks and my chess, except that it got attention.”

It did. The New York Times’ Sunday magazine, LIFE, Newsweek, Look—all seized on Lane, still just a few years into her chess career and hardly an established pro. She wasn’t famous for a woman chess player. She was quickly becoming famous, period, unlike any of her peers. For instance, Lane’s success came in the middle of a deeply competitive stretch by a woman named Gisela Gresser, who won nine national titles, five in the ‘60s. When Cavett tried to recall a female player on air in 1972, though, he didn’t think of Gresser—he thought of Lane.

“For this reason alone, I’m the most important American chess player,” she said in the New York Times in 1961. “People will be attracted to the game by a young, pretty girl. That’s why chess should support me. I’m bringing it publicity, and ultimately, money.”

Swagger like that boosted her allure. “I get a lot of love letters from other chess players,” she told the Times. “I read them, I laugh, and then I file them. Letters from grandmasters go on top.” She talked about how she hated to lose, how she couldn’t look at someone who beat her, how she certainly did not throw an ashtray at that one opponent. (She threw it at the table; when it broke, a piece struck him. But she didn’t throw at him.) It was another way in which she stood out from everyone else in women’s chess. But it didn’t come from a calculated media strategy or a desire to broaden her appeal beyond the game. It was the opposite: Lane cared about nothing except chess, and she couldn’t be bothered to invest time in hiding how she felt or practicing the genteel refinement shown by most fellow players. Chess was her life. Everything else felt incidental or inconvenient.

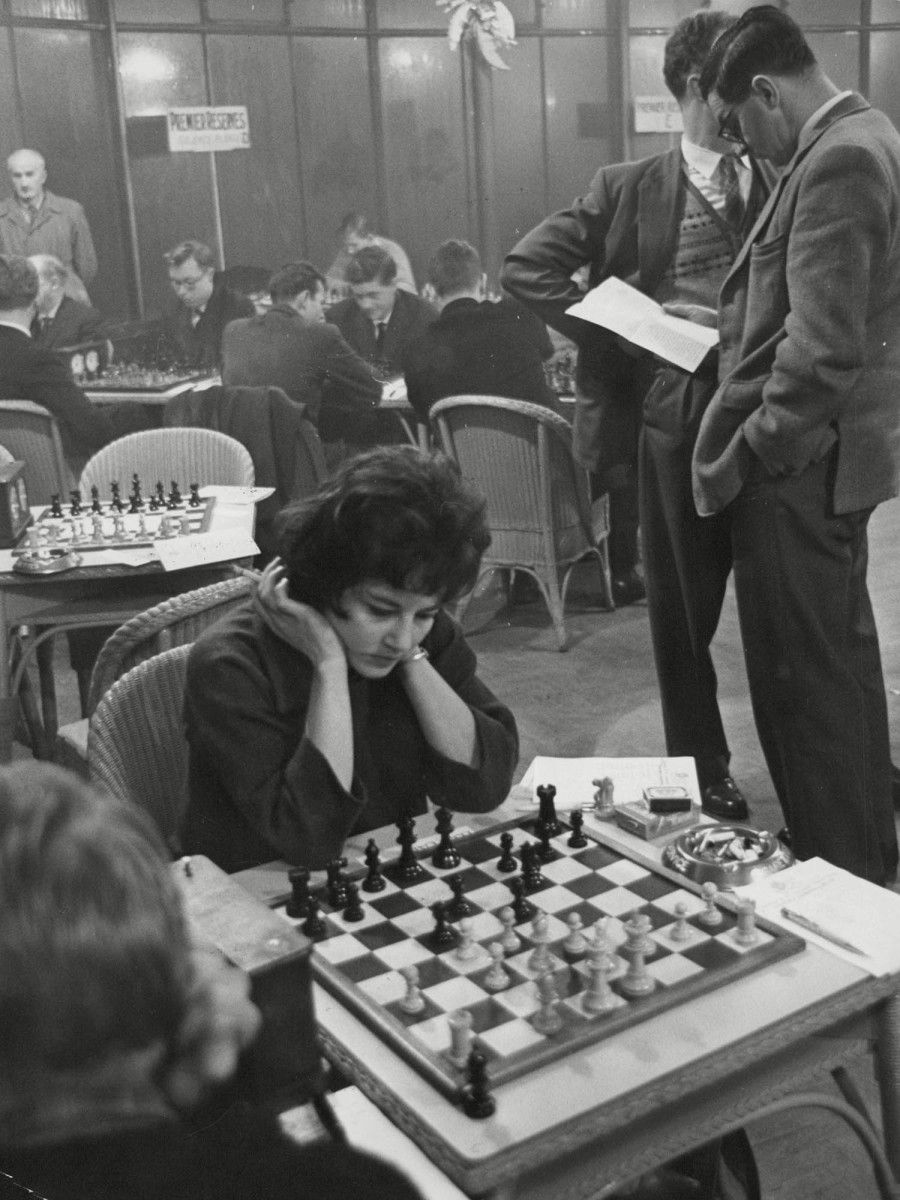

In 1962, she played again for the women’s national championship; this time, she came in second to Gresser, losing in the final round. The next year, she opened her chess club and began preparing for one of her biggest events: 1964’s candidates’ tournament for the world championship. She’d previously struggled in major international competition, finishing 14th out of 18 in the 1961 candidates’ tournament. (Gresser narrowly beat her, in 13th.) The 1964 event was a chance to redeem herself.

She didn’t. She finished 12th out of 18—though she did beat Gresser, in 14th. Lane was near the top of the women’s game in the U.S., but international competition demanded more, and she was beginning to realize that she might not be able to get there.

Part of that was talent; this was a maddening obstacle, but an understandable one. It was everything else that felt insidious. It was resources, time, money. There weren’t many serious prizes in American chess in the 1950s and 1960s, but there weren’t any for women. For most top female players—independently wealthy women, able to devote themselves to chess without worrying about being paid—that didn’t matter. Gresser’s father had been president of a steel company; her husband was a successful lawyer. She travelled widely in her free time, interested in music and art, and she frequently donated any prize money she received back to the tournament. Lane—unmarried, without family money, living in the tiny studio above her chess club—couldn’t afford that.

Her anger over the financial disparity had spiked in 1963, when she was passed over for a spot on the national team for the Women’s Chess Olympiad. It was customary for the country’s top two women to go; Lane was second at the time, behind Gresser. But she didn’t get the call. The US Chess Federation picked Gresser and a lower-ranked woman named Mary Bain. When Lane demanded an answer and went to the media to get it, the federation acknowledged that part of its reasoning had been that both Gresser and Bain could pay all of their own expenses for the tournament in Yugoslavia.

“Since when did you have to be a millionaires to represent your country in sport?” Lane asked the Associated Press.

A few years later, her frustration peaked. The 1966 U.S. Women’s Championship prize was $600. The U.S. Championship had just paid its men $6,000. A difference by a factor of ten—the same difference that women faced in the world championship in 2018—was simply too much.

“I decided to complain at the tournament,” Lane says. “And I found that I couldn’t get any of the other women to be interested in mounting any kind of complaint. They were all just too happy to be there.”

Lane was disappointed but not surprised. Even though her social life revolved around chess, she’d never had much opportunity (or, for that matter, inclination) to become friendly with other female players. Women rarely stopped by The Queen’s Pawn; almost her entire clientele was male. So she changed her approach, rounding up a group of male players from the club. Outside the tournament, they wore sandwich boards that read, “One Man Is Worth Ten Women?” and “What Good Is A King Without A Queen?”, and came up with a song: I’m gonna lay down my queen and pawn / Until the queen that fights gets paid like kings and knights / ‘Cause queens got appetites. A man burned his U.S. Chess Federation membership card in protest on the sidewalk.

Lane did well; Gresser tied her, meaning that they’d share the title of national champion. But the protest didn’t go over well—“the other women were embarrassed”—and it didn’t achieve her goal of closing the pay gap. The news coverage didn’t touch what she’d received for, say, revealing the name of her boyfriend. Chess Review ran it under the heading “Hoax or Reality?” suggesting that the protest was so ludicrous that it might as well be fake. Lane was frustrated, and she was beginning to sour on competitive chess.

She’d never been particularly fond of contest environments. “I loved playing the game, I loved going over the games, I loved watching other games,” she says. “But I can’t say that I ever really enjoyed tournament chess.” Increasingly, though, everything felt like a tournament, even casual games and simple match preparation. Over and over, she found herself obligated to play out the same scenario. Someone would mention that she was a women’s champion; inevitably, a man would ask why there were separate women’s tournaments in the first place, she’d explain the serious systemic imbalance, and he’d insist on challenging her.

“I felt it would be letting the idea of women’s chess down if I said no,” Lane says. “I felt like I was working all the time…. The idea that I was defending my title every time I sat down to play was an unpleasant feeling, even though I wasn’t really defending it. I just couldn’t put the title of women’s chess champion on the line every time I sat down to play.”

The women’s title had become a strain that she couldn’t escape; it was impossible to play without being conscious of the weight of her gender and legacy and place in the game. She was growing tired, and she didn’t see a chance of financial or cultural change. She was ready to drop competition.

So, in 1967, she did.

Since Lane walked away, change has come slowly in the sport. In some ways, little has changed; a wide gap in prize money remains. At a glance, this year’s championship discrepancy may not seem so extreme. At the 2018 World Chess Championship, the total prize was $1.1 million, and at the 2018 Women’s World Chess Championship, $450,000. Consider the playing field, though, and the gap looks far bigger. Two men split the $1.1 million; 64 women shared the $450,000. The women’s champion, Ju Wenjun, took home $60,000. Carlsen left with roughly $620,000.

“It’s about time to make the prize money gap shrink,” says Eva Repkova, chairwoman of the World Chess Federation’s Commission for Women in Chess. “For the men to have ten times more money? It’s time to move forward. I believe that it’s been partly just tradition—but, you know, things are changing.”

Beginning next year, the women’s minimum fund will be half of the open championship’s minimum—$550,000, split between two players in the new format. It’s a step toward remedying a difficult reality for top female players: It’s far easier for top male players to make a living from chess, allowing them to devote themselves to the game in a way that just isn’t possible for many women. That limits the female playing field and, in doing so, helps widen the gender gap.

The world championship’s new prize fund and structure have come after years of pushing from top female players. Among those who were especially vocal? Hou Yifan, unquestionably the best active female player. Ranked No. 91 in the world, she’s the highest rated woman by a large margin. She became the youngest to win the women’s championship in 2010, at age 16, and she’s won three times since.

But Hou found the system unfair. She says that she repeatedly brought her concerns to the World Chess Federation, to no avail. So she took a stand. After she won her fourth women’s championship in 2016, she decided that she would no longer play in a cycle that depended on knockout elimination.

“To win four times or six or eight doesn’t make so much difference to me,” she says. “On the contrary, if the women’s world championship system could be improved to a more organized structure that was good for future players? I thought there should be someone to step out.”

A new tournament structure, with a bigger prize fund, can be another step forward for the prestige of the women’s championship. But when it comes to increasing the stature of women in chess, better conditions for top players are only one piece of the puzzle. Another is building a foundation of young talent: a pipeline of girls who realize that the game has a place for them, too. Getting more female chess players, and better female chess players, requires breaking down the idea that chess is a primarily male game. The United States had never made a concentrated effort on the subject—but it is now.

“It’s a numbers game,” says Maureen Grimaud, chair of the women’s committee at the US Chess Federation. “It’s a total and complete numbers game. What the women’s committee is trying to do is to grow the base.”

When Grimaud joined the committee eight years ago, there was no blueprint for bringing girls to chess; the national federation had never really tried. So Grimaud set about finding an answer. Her committee went on the road to national chess events, particularly scholastic tournaments. “This had never been done before, so when we showed up, people were asking us, ‘What are you doing here?’” Grimaud says. “As soon as I’d tell people, ‘We’re trying to increase the number of female chess players here, because we just don’t see them’—as soon as we mentioned that, people were like, ‘Please help us! We need some help out here, because we’re trying to do the same thing at the local level!’”

The committee began hosting a girls’ room at national events, a space where female players could connect and realize that they weren’t alone. That, Grimaud says, was key. The biggest bloc of girls at a youth tournament is generally in kindergarten through third grade. As they get older, they start dropping off and become increasingly outnumbered by boys; giving them space to meet and form friendships is crucial. Beyond simply adding more girls, the goal is to make more girls feel comfortable—to build a culture for them to enjoy chess intellectually, competitively, socially.

“They were so excited to see that we had support for them,” Grimaud says. “They know that when they go back home, they might be the only female [chess player] out there for a 200-mile spread.”

There’s also been an increase in girls’ tournaments. The US Chess Federation sanctioned its first girls’ competition in 2003, the Susan Polgar Foundation Girls’ Invitational. The tournament is held annually now, along with several others. And the expansion of girls’ competitions doesn’t stop the country’s most talented female youth from playing in bigger mixed competitions. It simply encourages more girls to want to keep playing.

“It’s supply and demand. If girls and women want to play in them, it means they’re having fun and they’re networking with other girls and they’re using their brains in amazing ways that, in this culture, women sometimes aren’t allowed—the chance to just engross themselves in an intellectual activity,” Shahade says. “I don’t see them as a negative. If girls and women are signing up because they enjoy them, great, and if it starts to get to the point where some girls feel, Well, I’ve won this tournament before, I’m the top girl here, I really want to play in mixed competition with a wider net of people—and that usually does happen to girls, when they get really high ratings—that’s great, too.”

Most of the US Chess Federation’s recent spike in female membership, from 10% in 2009 to 14% in 2018, has come at the youth level. Grimaud points to national scholastic tournaments. From 2010 to 2018, for instance, participation at the junior high level increased by 23.7%—as girls’ participation in that group increased by 88.6%. And, as expected, more girls have led to more talented girls. In October, two eight-year-olds, Texas’ Rachael Li and Minnesota’s Alice Lee, earned an “expert” rating. No girl so young had ever become an expert; suddenly, there were two. Their wins broke another barrier: On US Chess’ October 2018 ranking of eight-year-old players, Li and Lee were No. 2 and No. 3. Only five years ago, there had been no girls in that list’s top 10, and just five in the top 80. Now, there were two in the top three, and 10 in the top 80.

“I feel like we have to flip the script,” Shahade says. “When people talk about girls and women in chess, sometimes they just go to negative things—reasons that they might not be as good. And while it seems innocent, because they’re just trying to find the answer to why not more, I think that sometimes it can be very pernicious.”

Yet there’s often a financial gap here, too. The difference can be harmful, even if it isn’t huge, reinforcing the idea that girls’ chess is worth less and making it more difficult for girls’ families to justify the cost of coaching and competition, Polgar says. She notes the invitation-only U.S. Junior Championship. It has a prize fund of $20,600; in the last five years, just one girl has qualified. A U.S. Girls’ Junior Championship, then, is structured in the same manner at the same club. Its total prize is $10,300.

“A difference of $10,000 wouldn’t kill them,” Polgar says. “It’s as if they, on purpose, want to make the point that girls don’t deserve as much.”

When Polgar first said that she wanted to be a grandmaster, she was told that it was impossible. “They literally told me that my family was crazy. Did we want to fly next, or go to the moon?” But she was the start of an unprecedented wave. From 1991 to 2000, four women became grandmasters, including Susan and her sister Judit. From 2001 to 2010, 18 women did the same. Since 2011, there have been another 13. With the changes to the Women’s World Championship, there’s hope for even more progress. The growth among girls gives hope, too—not just for individual players, but for the chess establishment to crack the code on women’s success and break down the cultural and financial burdens that once seemed inescapable.

Today, Lisa Lane lives on an isolated country road that branches off a marginally less isolated country road. The property is an hour and a half north of New York City, in the Hudson Valley’s Carmel Hamlet, but it feels more remote even than that. (The nearest neighboring institution is a monastery, three miles away.) Lane’s farmhouse was built in the 1850s, and it looks like it; the only major change has been an expansion to the kitchen. She moved to the region when she walked away from chess, and she’s been in this house for exactly forty years. She is now 80.

In 1960, a reporter named Neil Hickey interviewed her for The American Weekly. They hit it off; the following year, they ran into each other on the street and began dating. For the first time, Lane had something other than chess on her mind. In 1962, at the Hastings International Chess Congress in England, she couldn’t stop thinking about him. It irritated her. So she decided to walk out. “It interfered with my concentration,” she says now. “The first time that something interfered with my concentration!” In 1969, Lane and Hickey married.

While Lane spoke about her chess for this story, Hickey was in the next room, going through old photographs. (“She was such a big star in Russia. The Russians were all interested in chess, it was like their baseball, and she was like Mickey Mantle... So I love these pictures, they’re all stamped on the back from Russia.”) At the time, though, the relationship was a grand scandal. When Lane landed back in New York, she was swarmed by reporters and followed through the streets. LOVE CROWDS CHESS OFF THE BOARD, exclaimed the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. When Hickey refused to share any details, LISA’S LAD LEERY ran in the Associated Press.

“Brunette and beautiful though she is, Lisa Lane often seemed more like a chess-playing machine than a woman,” read the New York Daily News. “…But last week Lisa, 24, proved that she is woman first, chessmistress second. Falling in love wrecked her game.”

The coverage’s tone was typical. Her chess ability, her success, her personality—unladylike and unexpected, if not downright unseemly, for a woman. Falling in love? Finally, the media decided that she’d done something that made sense. Yet Lane’s perspective on the story hadn’t been that she’d fallen in love. It had been that she’d decided not to compete when she felt she couldn’t play to a certain standard. But that framework wasn’t used; no one even bothered to call her out as unprofessional for quitting in the middle of the tournament. In the public eye, her status as a chess player was now secondary to her status as a girl in love. Her story had become larger than herself, and her chess wasn’t part of it.

After she left chess, she looked for something else that could consume her in the same way. It didn’t take long. After reading Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, she grew interested in environmentalism, approaching it with the same obsession that she once had chess. She planted a vegetable garden and she composted; she made her own bread and churned her own butter. In 1971, she started a health food store, which she kept open until 2005. A “What Good Is A King Without A Queen?” board stayed in the basement until she closed up shop.

Chess did not define her life, as she’d expected it to. Instead, it was the beat and background of just one decade. The reverse is also true: Lane, once the most dynamic player in the women’s game, did not come to define it, either. Her career was cast as a glamorous blip on a more serious record; her story, if mentioned at all, is a wild footnote to the accounts of more accomplished women. But read differently, it’s a history of which women’s chess stories are told and who is given permission to shape them—to say nothing of which women are able to play in the first place.

Even after she quit, Lane still played chess casually; she couldn’t give up entirely. Online chess gave her a new outlet, though she hasn’t been able to play for several years, now that her eyesight has begun to fade.

“I have to figure out what to do with the rest of my life,” she says, with an intention that might feel remarkable even in someone several decades younger. “I haven’t figured that out yet. Not being able to drive, I have to find something that’ll make enough money for a private chauffeur.” She’s joking, but only a little bit. “I’ll figure it out.” She’s always been fond of hard plans, fairness, clean lines; she doesn’t want any differently for life in her eighties.

She went off the board once before, and it served her well enough, but she’s no longer interested: “The only thing I really ever stumbled into was being the U.S. Chess Champion.”