Wham-O Summer: Back to the Backyard

Enthroned on an aluminum-framed lawn chair, beSchlitzed in his own backyard, a man in the latter half of the 20th century rose to tend a smoldering Weber kettle grill, whose porcelain-enameled lid, black and shiny as a Cadillac hood, rendered him invincible. Brandished by the handle, it was a protective circle of steel—Captain America’s shield, emblematic of a time and place.

The backrest of that vacated lawn chair, with its basket weave of nylon straps, doubled as a strike zone for Wiffle ball. It was the kind of impartial and inanimate umpire that Major League Baseball is only now considering, but that has been with us, in plain sight, forever. Those lawn chairs were also collapsible, often while an aunt was attempting to sit down on one. Paper plate buckling beneath corn on the cob and coleslaw, she surveyed the backyard: swing set, sandbox and clothesline, whose billowing bed sheets said to the wielder of the Wiffle bat: The wind is blowing out.

In the heat shimmer of this mini-Wrigley an oscillating lawn sprinkler bowed down before the congregants, salaaming them. When neighborhood kids ran through the water, the sunlight refracting through the waving arcs revealed a rainbow.

Children shrieked, Weber seethed, cicadas skree’d from the trees. Can you hear the hissing of summer lawns, circa 1975, when Joni Mitchell sang of suburban ennui, of a woman stuck at home in July? In a ranch house on a hill / She could see the valley barbecues from her windowsill / See the blue pools in the squinting sun / Hear the hissing of summer lawns.

After a terrible spring of pandemic, the stuck-inside season just past, the summer of 2020 is already looking lost, unrelieved by the small mercies of attending a big league baseball game or visiting a public pool or taking an epic car ride to a distant amusement park. If many of us are left to gaze across the fence at the neighbors, bereft in our own backyards, marooned on our own Maple Streets, it may help to remember that the backyard—and the suburban subdivision, the city block, the local playground—was once a world unto itself, a place of sport and diversion, of tragedy and ingenuity, of derring-do and derring-don’t, of fun and boredom and mortal danger.

***

Fifty years ago, the federal government took aim at two national scourges: lawn darts and lung darts. In November 1970, for the first time, a warning label appeared on packs of nicotine sticks: “The Surgeon General has determined that cigarette smoking is dangerous to your health.” The following month, the Food and Drug Administration banned 39 toys as unsafe. Seven of them were various brands of lawn dart.

Lawn darts were metal missiles with heavy shafts, pointed tips and aerodynamic plastic fins. They were supposed to be thrown underhand, in a high arc, toward a small circle laid on the lawn, in a competition similar to horseshoes—except that the one-pound darts landed with as much as 23,000 pounds of force.

“An outdoor game for the family,” read every box of Jarts, the best-known brand. Now, Jarts were not to be confused with jorts, the cutoff jean shorts that were another staple of the wet hot American summer, though the two—Jarts, jorts—were often used in conjunction.

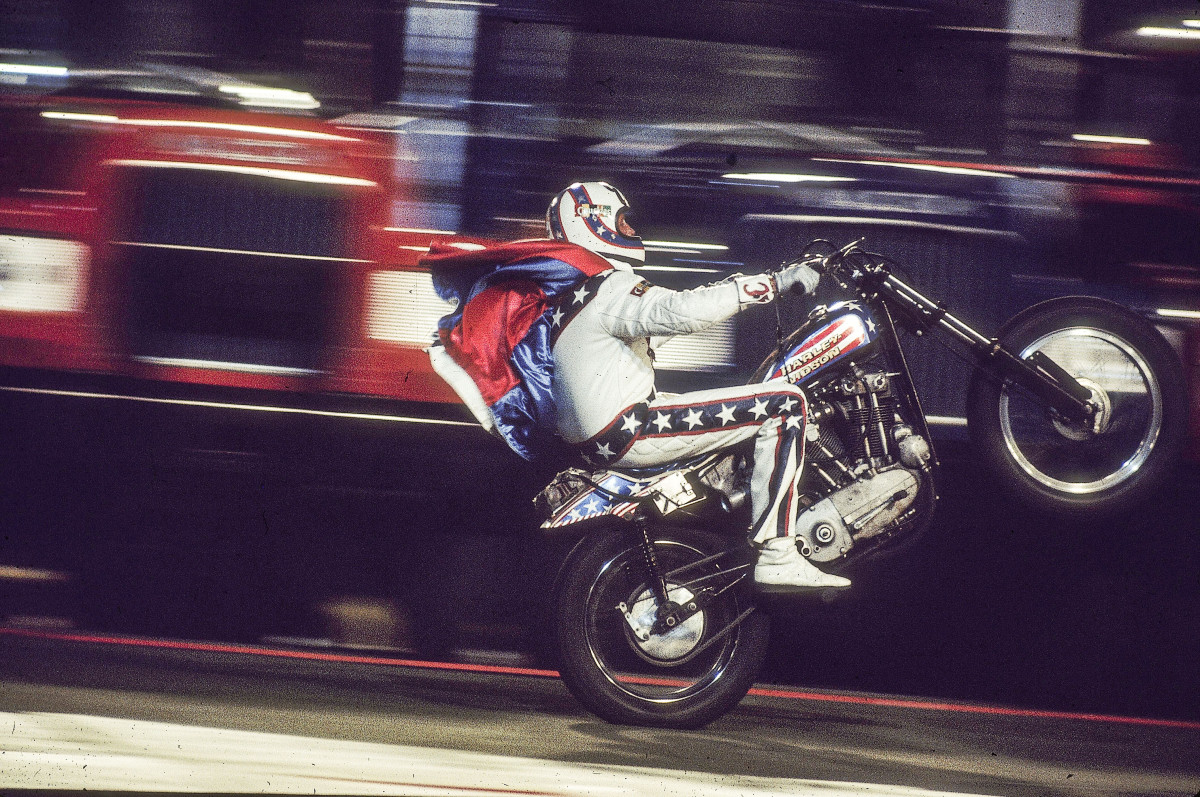

Boxed or left loose, despite the danger, lawn darts were found in garages across America, along with croquet mallets, archery sets, BB guns, Wrist Rocket slingshots and other weaponizable sporting goods, including the muscle bikes on which children of the era attempted to emulate the motorcycle daredevil Evel Knievel.

Before helicopter parenting was a phrase or a phenomenon, nightly newscasts asked, Do you know where your children are? And the answer was often No. “What are you going to do when Johnny goes down the street to play?” asked Edward M. Swartz, the author of Toys That Don’t Care, in 1973. “Are you going to follow him around and check all the toy boxes in the neighborhood?”

By then, “An outdoor game for the family” had become, on the box, “An outdoor game for adults.” As of 1970, the federal government decreed that lawn darts could not be marketed to children or sold as playthings. Their packaging suddenly required a warning label similar to those of cigarettes: “Not a toy for use by children. May cause serious or fatal injury.”

But they were still sold in sporting goods stores and frequently found their way into kids’ hands. One boy suffered permanent and severe brain damage and was blinded in his left eye after being struck in the head with a lawn dart at a New Jersey summer camp in 1970. (A jury later awarded his family $100,000.) In the same state, that same year, a six-year-old boy suffered a permanent eye injury at the hands of another child with a lawn dart. (The injured boy’s family won a $50,000 judgment.)

In ’72, in Pensacola, Fla., a seven-year-old was pierced by a lawn dart between his right eye and his nose. In ’73, a 16-year-old in Scranton, Pa., had a lawn dart lodged in his forehead, requiring removal by a neurosurgeon. In ’74, a toddler in Des Moines was hospitalized with a head wound after being hit by a lawn dart at his first birthday party. Two years later, in Rock Island, Ill., a five-year-old in the city’s summer rec program had a lawn dart embedded in her skull.

In the midst of all this tragedy, in 1972, Congress created the independent Consumer Product Safety Commission to curb such injuries. Like fire (or fireworks), however, lawn darts remained a source of fascination and dread to children, and they remained accessible for another decade and a half. A boy could pick one up, heft it in his hand, and feel the latent lethality. But not every toy was Chekhov’s gun, bound to do harm, and the backyard remained, more often, a place of hose-enabled wonder.

***

The Thomas Edison of summer fun was the Wham-O Manufacturing Company, based in San Gabriel, Calif., the Menlo Park of backyard bedlam. Among other gifts, Wham-O gave America the Slip ’N Slide, a 25-foot sheet of polyethylene on which children still dive headlong, sliding fists-forward in the manner of Pete Rose or Orioles catcher Rick Dempsey, who used the infield tarp as a launching pad during rain delays, splashing into home plate like a landing seaplane. Irrigated by garden hose, the Slip ’N Slide was also the perfect vehicle for landlocked Midwesterners, deprived of ocean waves, to surf on turf. There is an art to remaining upright while hydroplaning barefoot for eight yards, before abruptly stopping, as at the end of a moving sidewalk.

In this way, the garden hose was a life-giving umbilical cord, delivering nutrients straight from the municipal water supply and powering what seemed like half of the Wham-O product line, including Willy Water Bug (“Tubes in Willy’s hat lift and spray water”) and the Water Wiggle (“Just hook to your garden hose and watch it chase kids, play tag and water the lawn”). Wham-O sold 2.5 million Water Wiggles before the product was pulled in 1978. Two young children had drowned, three years apart, while drinking from the seven-foot hose attachment of a dismantled Water Wiggle.

Children were naturally drawn to garden hoses, which could be weaponized as water cannons or provide the payload to an arsenal of water balloons. With the application of a thumb to the spray, the garden hose became a misting station, or a pressure washer for blasting beach sand from ankles and hosing down a soaped up (and souped up) El Camino in the driveway. The garden hose filled kiddie pools and lubricated slides and generally served as suburbia’s version of the open fire hydrant on a city street corner.

That hose was, above all, a drinking fountain—between-innings relief during scorching games of Wiffle ball. “When you’re hot and thirsty outside, few things look more inviting than the cool water coming from a garden hose,” noted a syndicated newspaper story that ran nationwide in 1974. “Don’t drink from it. The nozzle may have rust on it, or insecticide. Don’t take the chance of cutting your mouth or drinking dirty water.”

Danger lurked everywhere in the backyard. Wham-O’s insuperably named Super Elastic Bubble Plastic came in a tube, like toothpaste or model airplane glue, and emitted the latter’s noxious fumes, adding to the olfactory stew of propane and cut grass. When blown through a straw, the paste created a plasticine orb. Alas, that paste was also “highly inflammable and produced an acetate vapour which was intensely irritating to the throat if inhaled,” as one Australian health authority noted when Super Elastic Bubble Plastic was withdrawn from that market in 1974. Containing a material common to nail polish remover, Super Elastic Bubble Plastic (and similar products marketed under other names) drew the attention of Consumers Union, publisher of Consumer Reports, which called for the product’s withdrawal in the U.S., citing, among other consumer complaints, “a druglike euphoria” induced by the fumes. And so Super Elastic Bubble Plastic, like the soap bubbles it emulated, eventually vanished into thin air.

For the most part, though, Wham-O remained a purveyor of “endless fun,” as the company’s slogan said, and its anarchic commercials continued to be irresistible to 20th-century children, and more than a few adults. In the summer of 1974, a Clevelander named Alex Stein and his whippet, Ashley, invaded the field at Dodger Stadium as the home team was playing the Reds. Stein threw Ashley a Frisbee in the outfield, and the whippet caught it in his teeth, something Dodgers outfielder Tom Paciorek never did in that same patch of grass. Stein was arrested and fined $250, but surely his moment in the sun was worth it, especially when Stein announced that his fine had been paid by a benefactor: the Wham-O Manufacturing Company of nearby San Gabriel, makers of the Frisbee.

Frisbees were enjoying a golden age, with men and women in short shorts and long tube socks leaping skyward in backyards and public parks. President Jimmy Carter would catch one on the White House lawn. Father-and-daughter actors Ryan and Tatum O’Neal reportedly traveled with a Frisbee in their suitcase. Marooned Frisbees were fixtures on rooftops across America, along with guttered tennis balls and rusting aerial antennas. Those antennas pulled in the latest heroics of Evel Knievel—spectacles soon to be imitated in American backyards and driveways and cul-de-sacs.

That summer of 1974, during the yearlong buildup to his attempted leap of Idaho’s Snake River Canyon in a rocket-powered SkyCycle, Knievel was among the most famous men in the U.S. Gerald Ford was asked that year, by talk-show host Dick Cavett, whether he could identify Knievel, and the vice president guessed that the Evel in question was probably a rock star. To the nation’s children, that’s exactly what Knievel was, and they—we—were all trying to imitate him with homemade ramps, on muscle bikes ill-suited for the purpose: Schwinn Sting-Rays and CCM Mustangs and Huffy Wranglers. “If 14-year-olds could vote,” Knievel said that summer when Richard Nixon resigned, “I would have been elected president of the United States.”

Surgeon general would have been a more apt position. A seven-year-old boy in Muncie, Ind., watched a Knievel movie on ABC, immediately attempted a bicycle jump and required surgery to remove his spleen and half his pancreas. A 14-year-old boy in Utica, N.Y., was paralyzed after using a car hood as a ramp. A six-year-old boy in Brooklyn was severely injured using milk crates and a plank as his launching pad. A 10-year-old boy in Philadelphia ruptured his spleen jumping barrels. The head of the Rockland County (N.Y.) Medical Society referred to the days following Knievel’s failed Snake River Canyon attempt as an “epidemic.” By then, Nyack Hospital, in suburban New York City, was seeing 30 Knievel-inspired cases a week. Across the nation newspapers recounted the carnage of their own Knievel casualties: a ruptured liver, two broken arms, two broken wrists, a concussion . . .

U.S. Representative John Murphy of New York had argued for the FCC to ban Knievel’s Snake River Canyon jump from television, saying it was “in large part aimed at the nation’s children, without the slightest regard for its consequences.” Of course, there were consequences, many of which accrued to Knievel: Three months after he crashed into the Snake River Canyon, his action figure and Stunt Cycle set was the most popular Christmas toy.

Evel himself drove a 1971 Cadillac station wagon with a luggage rack and wood-panel racing stripes, the cool-dad version of what our fathers drove on interminable road trips to distant summer vacation destinations—kids stuck in the way back with nothing to look at for hours on end, save for other kids, looking back at us forlornly from the way backs of their own stifling station wagons.

It took decades, but Americans, for the most part, stopped piloting their bicycles into the afternoon sky, among other reckless acts. In 1978, 14% of people polled claimed to wear their seatbelts in the car; now that number is 90%. In the late 1980s, one in 20 young bicycle riders was wearing a helmet. Now, bike helmets on children are ubiquitous, a powerful safety measure, especially when coupled with the disappearance of Evel Knievel as a cultural force among school-aged kids.

***

In 1987, seven-year-old Michelle Snow was playing with dolls in the front yard of her home in Riverside, Calif., when an errant lawn dart, overthrown by a child in the backyard, struck and killed her. The girl’s father, David, had never wanted the lawn darts in the first place, but they came packaged with a volleyball net that he’d purchased. In the days after his daughter’s death, the grieving father began speaking to reporters and traveled to Washington to lobby lawmakers, generally devoting his days and nights to a cause he never wanted to champion: an outright ban on the sale of lawn darts. “I want this to be over,” he told the Los Angeles Times that year. “Once I pick up a paper and see that they’re banned, I’m going to crawl back under a rock and never talk about lawn darts again.”

The following June, the Consumer Product Safety Commission estimated that 6,100 people had been injured by lawn darts between 1978 and ’86, some 80% of them younger than 15. Three children—ages four, seven and 13—had died. Finally, in October ’88, an 11-year-old girl in Tennessee was placed in a medically induced coma after a lawn dart penetrated her skull. Three days later, David Snow picked up his paper to see that the CPSC had banned lawn darts.

These days, so-called “lawn darts” bear soft, blunt, weighted “tips” that allow a landed dart to balance upright on the backyard grass. That backyard in some ways looks the same as it did 50 years ago. Today’s homeowner, afloat on an inflatable alligator in the above-ground pool, might see the same things their ancestors saw, and hear what they heard. Winking fireflies, croaking frogs, stridulating crickets.

But the world is different. Captain America wears a seatbelt, and probably sunscreen. His Schlitz is a craft beer. His child is drinking from a water bottle, not the hose.

In decades past, the sunbather beached in the backyard wore suntan lotion, wanting an accelerant, not a deterrent. People found the sun absorbing, not repelling, when climate change was not yet nightmare fuel. During the Fourth of July Salute to Savings at Ribordy Drugs in Noblesville, Ind., in 1975, the staycationing homeowner could buy a Wiffle ball and bat for $1.50, a Styrofoam cooler for 99 cents and an aerosol can of Sudden Tan bronzing foam by Coppertone (“Got a minute? Get a tan!”) for $2.39. That’s $4.88 for a full Independence Day of backyard fun, melanoma included.

While tragedy and freak accidents persist, lawn darts and grade-school bike jumps have largely gone extinct. Their painful lessons, however, inform our own summers. These faded pastimes are invisible but still with us, like ghost runners in a game of Wiffle ball. The CPSC’s reports on public playground safety once made for horrifying reading. (Think: white-hot metal slides depositing children onto concrete landings.) More diving boards are now removed than installed on backyard swimming pools. Everything is ostensibly safer, even as it feels more dangerous in this lost summer of pandemic.

But then every summer is a lost summer, consigned each September to history and memory. If the first weeks of COVID-19 felt like the end days, like time to build an ark—well, a man already did that, and his name wasn’t Noah. For 3 1/2 years in the antediluvian 1970s, Tom Meanley labored to build a 70-ton riverboat in his Memphis backyard. It would be three decks high, with a great paddlewheel at its stern, a steamer as long as a 10-story building is tall, so large that his property line eventually could not contain it. That’s when he put it on a house mover and trucked it 10 miles to the Mississippi River, where Meanley finished the vessel on the water and floated away downriver on it, like Huck Finn.

It’s a timeless American story, and one that will echo again this summer, with a man sitting in his own backyard, dreaming of escape.