How Empty Stadiums Could Influence Referee Decision-Making

If you think Auburn-Alabama makes for a fierce rivalry, it’s an intrastate cuddle puddle compared to the Derby di Sicilia. Since 1935, the two most prominent soccer clubs in Sicily—Calcio Catania and Palermo Calcio—have fought for supremacy in what is less an annual Serie A soccer match than a tribal war. The games would, ritually, devolve into riots, the worst coming in 2007 when a policeman was killed as he tried to break up a brawl among fans outside Stadio Angelo Massimino.

In the wake of that tragedy, the Italian government took a dramatic step. It forced soccer teams with deficient security standards at their stadium to play their home games without spectators. Apart from improving security at games—there has, happily, been a sharp decrease in riots since—these “closed-door matches” inadvertently made a great contribution to social psychology. And they offer a preview of what to expect when the NBA, MLS, MLB, WNBA and other U.S. sports leagues resume play in front of no live audience. (And the NWSL, for its part, has already resumed, without fans in attendance.)

After the Calcio-Palermo brawl, two Swedish economists, Per Pettersson-Lidbom and Mikael Priks, studied the various Italian soccer matches played in the empty venues. And they found something remarkable. In Serie A, as in most sports leagues worldwide, the home team won the majority of the matches, according to the study, published in the journal Economics Letters. Why? For a variety of possible reasons, but, chief among them, home teams received the majority of favorable calls from the officials. In Serie A—as in virtually all leagues—home teams received fewer red cards and yellow cards, and fewer penalty and foul calls. When home teams were trailing, they received more injury time, the minutes that officials discretionarily tack onto the end of games, increasing their odds of catching up. When home teams were leading, injury time dwindled.

Yet when the Swedish economists looked at games played between Serie A teams with no fans in the stands, the home team advantage effectively vanished. Teams didn’t win at home any more than on the road.

And when no fans were in the stands, the home/away penalty differential shriveled. The favorable calls conferred on the home team dropped by 23%–70%, depending on the type of calls (a decline of 23% for fouls, 26% for yellow cards and 70% for red cards). Subjective close calls no longer favored the home team. Injury time favoring the home team declined as well.

The researchers looked closely at officiating crews pre- and post-riot. They noted that the same referees overseeing the same two teams in the same stadium behaved dramatically differently when spectators were present, versus when no one was watching.

The Italian government ban also extended to the Serie B league, the next-highest level of Italian soccer. Normally, the attendance in Serie B is about half of Serie A, and the home-field advantage in Serie B is about half of what it is in Serie A. When the researchers studied Serie B results, they found more evidence to support a conclusion that the presence of fans impacts refs. In the fanless games, the effect of officiating was … roughly half of what it was in Serie A.

Why would officials call a game so differently based on the presence of a crowd? Let’s dispense with the conspiracy theories: It is not because officials are biased, much less because they are corrupt. It is because they are human. As such, they are susceptible to the powerful force that is social influence.

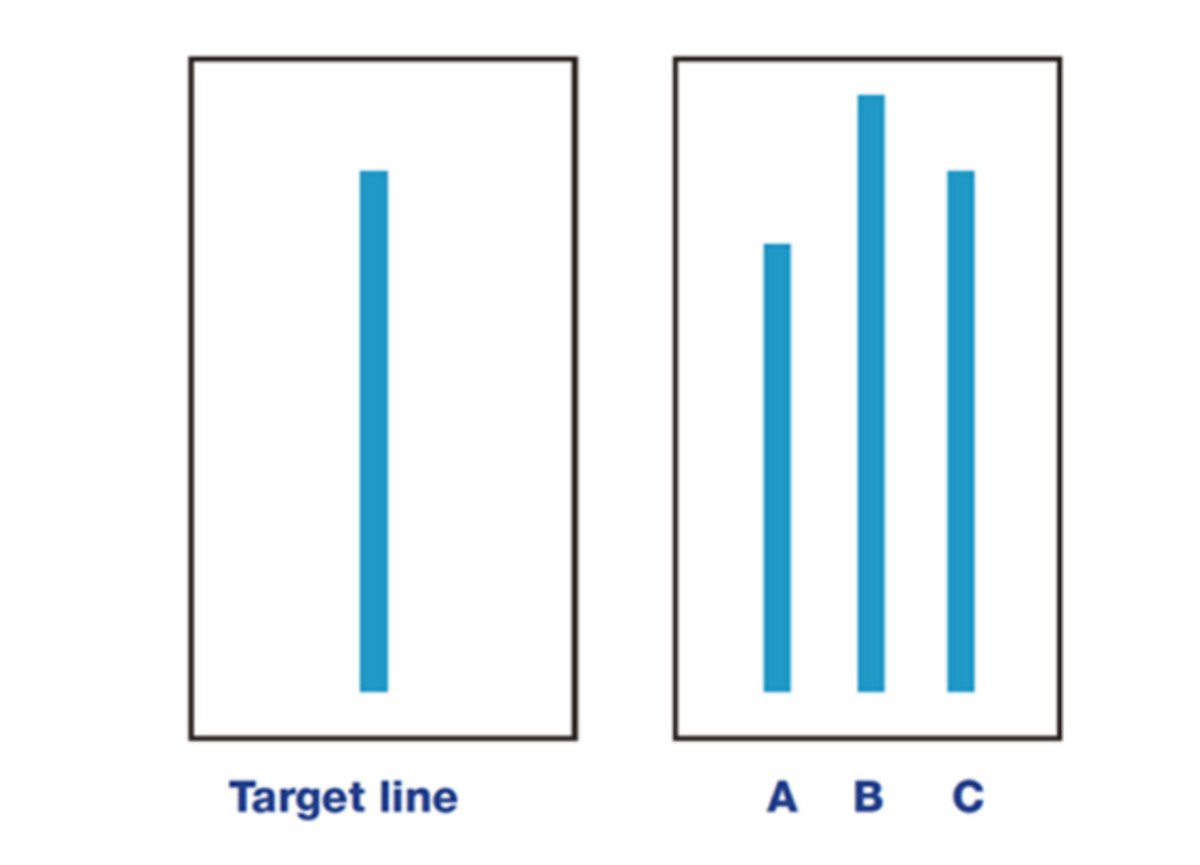

One such influence is conformity bias, a desire to conform to a group’s opinion. In a classic experiment, the psychologist Solomon Asch asked subjects to make a value judgement about the length of a line.

The answer was fairly obvious.

But Asch then had seven confederates (or actors) enter the room and give a different answer. In the majority of the cases, the subject—despite confidence in their own answer—changed to conform to the group. Asch also found that subjects felt enormous stress when giving a response at odds with the majority, even though they were confident that they were right. The takeaway was that human beings conform: 1) because they want to fit in with the group, 2) because they believe the group is better informed than they are, and 3) because siding with a group alleviates the stress of being an outlier, especially in an ambiguous situation.

Transpose this to sports officials in front of a rabid, partisan crowd. In trying to make the right call, it’s easy to see how they would conform to a larger group’s opinion, swayed by tens of thousands of people witnessing the exact same play they did. As the saying goes in psychology, “I’ll see it when I believe it.” Call it a charge and 20,000 cheer in agreement; call it a block and 20,000 fans howl disapprovingly and question the virtue of your mother. Referees do not intend this favoritism. They’re probably not even aware of it. But it is a natural human response.

At least in some sports, home advantage has declined in recent years. In the NBA, for instance, the home teams may have won at a 68.5% (!) clip in 1976–77, but now win at around 53%. In baseball, we are coming off a World Series in which the road team, for the first time ever, won all seven games.

In the NFL, home advantage was less than 52% last season. Crowds are louder than ever, and teams have never been more creative in seeking incremental home advantage. One example among many: the sign in the Broncos’ visitors’ locker room warning, forebodingly, what to do in case of altitude sickness. Why would home advantage be falling? The presence of replay and coaches’ challenges provides the best explanation.

When those close calls, made disproportionately in favor of home teams, can be overturned on appeal—reviewed in a vacuum, the equivalent of a fan-free environment—it erodes the advantage of playing host.

Interestingly, if the presence of fans—and then, the absence of fans—had an impact on the officiating, it did not have a demonstrable effect on the athletes. There may have been no audible cheering and no booing and no riots in the stands, but the 22 men on the field hardly seemed to notice. They shot virtually the exact same percentage of goals on target, passed with the same accuracy and made the same number of tackles. Fans or no fans, they played identically. (This mirrors other sports, where there is little data to suggest that NBA players’ free throw percentages or NHL penalty shoot-outs are impacted by home-versus-road or the size of crowds.)

So what should be expected when games are played in fan-free, neutral site environments? A small handful of NWSL and international games isn’t enough to say just yet. Officials’ calls—unlikely to be impacted by many factors other than judgment—are likely to even out. Reviews, replays and challenges are likely to even out. (And to be summoned less often.) The betting lines, which often confer as many as four additional points based on where the game is played, are likely to even out as well. In short, the “home” and “road” designation will be as arbitrary as the pregame coin flip. “Home cooking” will not be on the menu.

Perhaps a more instructive question: What can we learn from this period? That is, how can officials keep this level of neutrality once we exit the sports biosphere and the games resume as before? How do we replicate these conditions, so calls are based on cold judgment, not hot social influence?

A number of leagues, including the NBA, have recently started to include discussions on social psychology and behavioral biases in their training of officials. But blocking out crowds is, as former NBA ref Gary Benson notes, “easier said than done.”

Games played behind closed doors will accelerate the trend of evening out calls and, therefore, home advantage. But human psychology is a powerful force. If you listen to fans after a disagreeable call, officials may be blind. But they are human.

***

Some of this material was adapted from the book Scorecasting: The Hidden Influences Behind How Sports Are Played and Games Are Won, by L. Jon Wertheim and Toby Moskowitz.