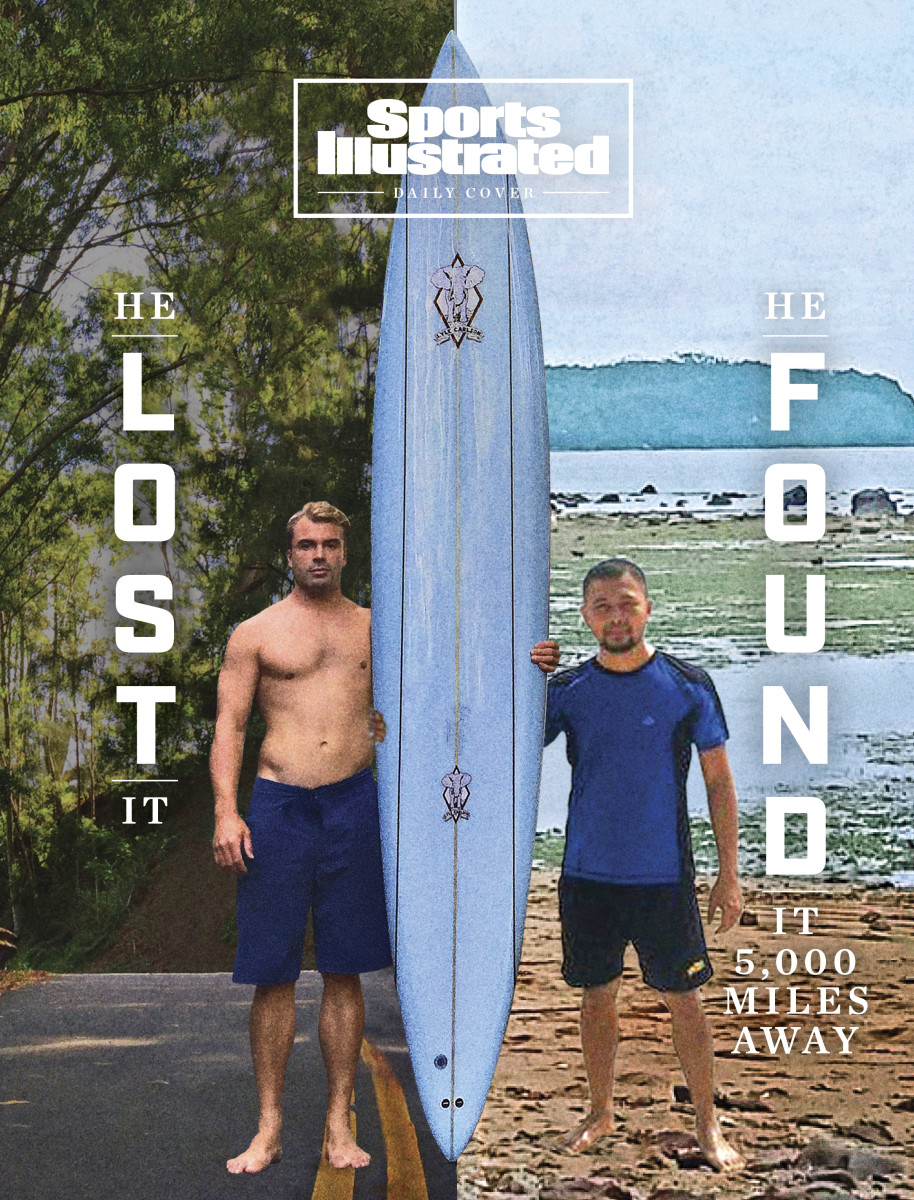

An Ocean Separated Them. A Surfboard Connected Them. See: 2020 Has a Happy Story After All

In a year of a billion Zoom calls born from a global pandemic, after seven months as strange as any stretch in human history, two men—separated by thousands of miles, a language barrier and a world divided—meet one afternoon in August over video conference. Each one knows exactly how he arrived here, how improbable this digital crossing is. But as they dial in, neither, really, can believe it.

On one end is a 35-year-old professional photographer and amateur surfer, fidgeting in his bedroom in Hawaii. Tanned and T-shirted, he’s fixing his hair and complaining of a sunburn. His AC is cranking and the blinds are drawn to combat the rays from outside. He looks nervous, as if embarking on a virtual blind date.

On the other end is a 38-year-old schoolteacher in the Philippines who’s squeezing this call in between classes. Goateed, with close-cropped black hair, he speaks in imperfect English, profusely polite, all Thank yous and smiles. He addresses the other caller as “Sir.”

The surfer stammers, seemingly out of jubilation and confusion and the sheer absurdity of everything that led him here. “It’s pretty wild. … It’s pretty awesome. … I don’t know. …”

The conversation twists from awkward banter to talk of some higher purpose, how the two men are now bonded forever by one prized possession. The one that cost the surfer his entire savings, that he’d come to treasure and cherish like a family member. And then they dive deeper, into the cosmos, considering fate and purpose, loss and discoveries, the nature of humankind and what really matters to them. As these two callers recently discovered, we’re all more connected than we think.

Finally, the teacher reaches off-camera and with both hands conjures a large object, holding it up for display.

My baby, the surfer thinks.

***

Go back two years. Doug Falter was paddling out toward the kind of Waimea Bay waves that filmmakers live for—those big, cresting monsters that rise, rise, rise and fold over, forming a tunnel that propels elite surfers toward nirvana. Falter was one of those seekers who gives up a “normal” life, moves to Hawaii and settles on the North Shore of Oahu, making just enough money to chase this particular brand of high.

Already, on that afternoon in February of 2018, Falter says he had conquered seven waves that most humans would sprint away from, praying to the gods. Greedy, sure, but with sunset fast approaching, he wanted to try for one more. The clock ticked past 6 p.m. He figured he had 20 minutes.

From afar, a friend kept a loose watch. Lyle Carlson had crafted some of the world’s finest boards, including Falter’s, but right now he was keeping his eyes peeled as Doug paddle-paddle-paddled into the fray. Then Falter disappeared, caught, as far as Carlson could tell, between waves, trying to swim down so he wasn’t pummeled with the force of an NFL defense.

Carlson knew all the risks, and they were all severe. The force of a crash could break bones, contort spines, deliver concussions. A surfer could drown or, if his ride shifted wildly, quickly, the heavy leash that connected him to his board could tear a ligament. In Waimea Bay alone, Carlson estimates that thousands of backs have been destroyed. “That size of wave kills people, man,” he says. “When you’re standing near the lip of a giant one, it sounds like a jet engine. … And then it explodes, like a bomb going off, over and over.”

Faced with the peril of a wave crashing down, a surfer has few options. This is no jiu jitsu match, with the option to submit; it’s no basketball game, with allowance for a timeout. Back up for air, Falter tried to grab his leash and pull toward the board, so he could float to safety. But when he yanked this time, he could feel it: The board was no longer attached.

The deep, frenzied panic that rose up right then? He remembers it now, vividly. But that panic came not from any heightened sense of personal danger. He was concerned about his board, always.

In Waimea Bay, the current acts like a horseshoe, with waves flowing in one end of the bay, following the shoreline, then curving out at the other end. Still, Falter managed to swim back in. He stumbled onto the beach and ran along the sand until he reached a rocky outpost, climbing as high and as fast as he could.

Darkness was descending. He couldn’t see the board.

Falter rushed home and logged onto Surfline.com, where he could access the remote cameras the website had trained on those big waves. He rewound until he found himself flailing in the water. Though he hadn’t known it at the time, the video showed that he was still close to the board as he swam toward the shore. Close, but then not. Eventually the board sailed out the other side of the horseshoe and into the deep ocean.

***

Back in Columbus, Ohio, where Falter grew up and then toiled as a Carmax mechanic until he was 20, surfing had hardly been in the forecast. He’d seen the ocean sparingly, only on short vacations to Florida. But a restlessness set in, and in 2006 he moved to the Tampa Bay area for no reason he can remember. Eventually he logged onto Roommates.com, where a photo in one post caught his soul’s attention: a potential roomie waxing down a Channel Islands–brand surfboard. Falter couldn’t avert his eyes. This man, this board, this existence—it was exactly what he wanted.

Falter moved in with Sal Ventimiglia, bought his own board for $50 on Craigslist—an '80s retro model, painted an obnoxious neon pink—and with his new landlord-buddy drove east in the afternoons to Melbourne and Cocoa Beach and Sebastian Inlet, always in search of breaks, but also of some greater meaning. Ventimiglia laughs now at how Falter could hardly sit on his new ride at first, let alone manage even the smallest wave.

Not that it mattered. “He was hooked,” says Ventimiglia of a friend who was clearly growing disenchanted with his day job. Ventimiglia remembers a man approaching existential crisis, searching for a higher purpose.

On a whim Falter traveled to Costa Rica, alone. He stayed for a week in Jaco, a pretty little surf town on the west coast. He slept in hostels. Bummed around the beach. Made friends with strangers who spun elaborate stories about world travels, fueling Falter’s own desire for more. He heard about Aquabumps, a gallery of surf photography in Australia, run by a photographer named Eugene Tan, and found inspiration in Tan’s images. He bought a GoPro and started to snap away, taking thousands of pictures, some of them grabbing hundreds of likes on Instagram and later on his own website. And the gratification sparked his next move.

In 2011 he packed up for Hawaii, where he would pursue surfing and photography, hoping that one dream could fund the other. He sold almost everything he owned and flew over the Pacific with two suitcases, knowing not a single person where he landed. He gave himself five years—college, basically—to figure out the future.

***

Driving from the airport to the beach, Falter was stunned by the sheer size of the waves in Waimea Bay. He settled into Backpackers, a hostel on the North Shore, where he worked three hours each day cleaning rooms to cover his stay. He purchased a Canon 70, upgrading his equipment, and read the manual over and over. He snapped pics and studied Tan, aspiring to live up to a photographer whose work so vividly captured beach life and ocean rhythms—and then, on the way to the grocery store one afternoon, he bumped into Tan himself.

The gallerist saw a bit of his own arc in Falter—“sold everything, quit his job; kinda like my story 21 years ago,” he says—and over time became Doug’s mentor. Tan showed him where to find the gigantic waves, like the Banzai Pipeline, and then how to advance close enough to shoot the surfers pursuing their highs.

The first time Falter ventured out into the infamous Pipeline, he swam with fins, no camera. He wanted to get a feel for it. This was one of the most dangerous spots in surfing. But as Falter went deeper and deeper, into the danger, his internal compass surprised him. The farther out he swam, the calmer he felt. “Basically, I was conquering fears,” he says.

Falter’s confidence was growing on both fronts. He wanted to capture those surfers on the massive, hazardous waves, and he had the skills to do that—but he also wanted to be them. In 2015, another chance meeting defined his path. He needed a big-wave board, and he bumped into one of the foremost shapers.

Lyle Carlson had shaped his first board when he was 16, apprenticing for years under a legend of the craft, Dick Brewer, each day the equivalent of a shooting clinic with Michael Jordan. Now 41, Carlson estimates that he’s shaped more than 7,000 boards in a quarter-century, spending days or weeks on each, carving the foam and sculpting the slope, every last detail carefully considered.

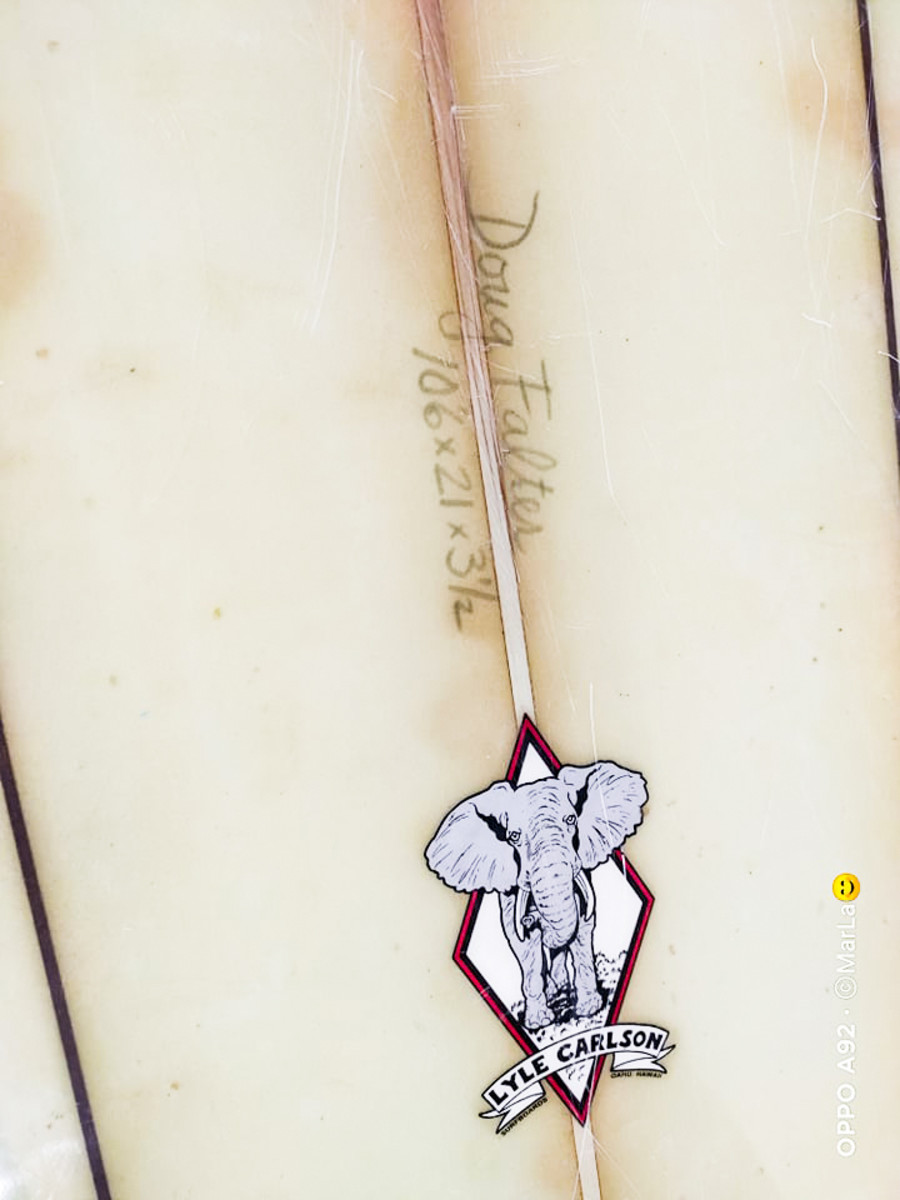

Carlson emphasizes: There’s not another exact replica in existence of the custom board he made for Falter. Over 10 feet long, 21 inches wide and three and a half inches thick, his creation weighed a hefty 35 pounds—“more like a tank,” he says—and bore Carlson’s trademark elephant head emblem, one big and one small on each side.

A pro surfer might buy several of Carlson’s boards—in case one breaks, or to counter varied and unpredictable conditions—but for Falter that was never in the cards. Twelve hundred dollars for materials, $200 for the fins, $100 for the leash. … This is “like extreme skiing,” says Carlson. “If you want to do it properly, you have to put a lot of money into it.” The only thing Falter owned that had cost him more was his car, an old Volvo sedan that he snagged for $2,000. That ride never started for him in the rain. But the board he invested in never failed.

“My baby,” as Falter calls it, would become his most valued possession. Even if the architect hadn’t exactly nailed it at first. When Carlson delivered the finished product in October 2015, Falter pointed out: He’d asked for a light-blue hue, but it turned out dark. Carlson admits now that he made a mistake—“like if you ordered a Ferrari and got red when you asked for yellow”—but he also wonders if his subconscious hadn’t guided him. He always pushes clients toward dark or distinct colors, so the board can be found more easily in the water. A lighter-colored board, detached from its leash, might, say, blend into the ocean. But light blue was what Falter wanted.

So Carlson went back to work, fixing the coloring. Finally, Falter had his own custom board, and with it he tamed wave after building-sized wave, with pictures and video to prove it. “That board meant so much to me,” he says. Finally, he felt fulfilled. He vowed to hang his baby on a mantle one day, maybe above a roaring fireplace, beside cherished family photos. The board would announce his death-defying hobby. Like a big, sloped deer head, it would be a trophy from his surfing hunt.

***

If Doug Falter had finally found himself, Giovanne Branzuela was still looking. Born in the Sarangani Province, at the southern tip of the Philippines, with its fruit plantations and commercial fish farms, he fell in love early with the ocean alongside his father, a fisherman. Dad would take Giovanne and his cousins for trips into the sparkling blue waters, pointing out exotic fish, eating the freshest catch, showing off the ocean’s inherent beauty. Those adventures stoked Branzuela’s desire to surf, and eventually he started studying videos online at night of big waves being conquered. Dreaming—but of what exactly, he wasn’t sure.

Wanting to surf was one thing. Figuring out how was a problem. Branzuela lived far from any big waves, in a country with little enthusiasm for the sport. He couldn’t afford any equipment, but even if a bag of cash fell from the sky, there was nowhere to buy a board anyway.

Eventually he gave up on riding. He became a middle school teacher, then a high school teacher. He loved the impact that he could have on his students and the lessons they taught him in return. He still watched his surfing videos, but he also married, settled down, had two kids, focused on his family and his students. Somewhere in all of this, he moved, and next door to his new house lived a fisherman who in his nets caught all sorts of oddities: shoes, sails, boat parts …

One day in August 2018, this fisherman dropped anchor near a small, egg-shaped island off the southern coast. When he raised his nets, a large, torpedo-shaped object was ensnared with the catch.

***

Maybe light blue hadn’t been the best color, after all.

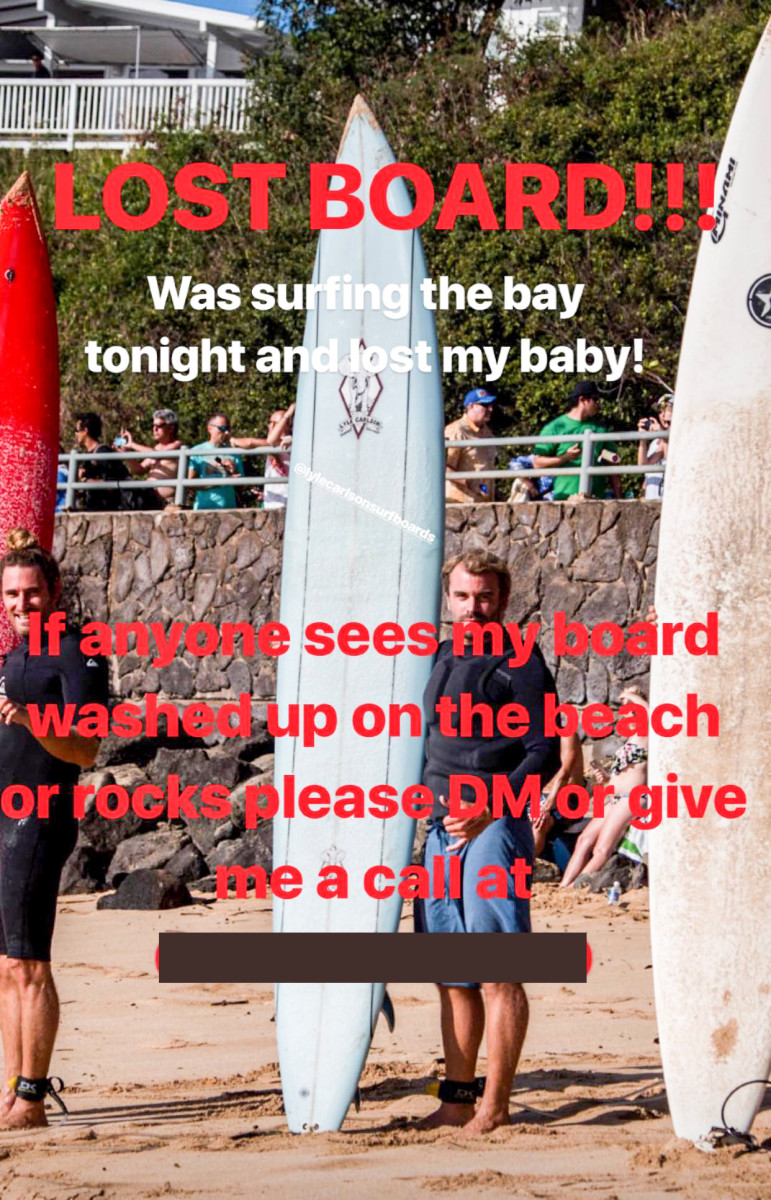

Falter’s search began immediately and continued for months. He posted messages on Facebook and plastered photos across telephone poles around Waimea Bay—him holding his board, along with his cellphone number—as if he were a suburban dad searching for a lost puppy. He enlisted friends to help and scoured Craigslist and surfing forums; maybe it would turn up for sale somewhere nearby. He’d heard stories about boards that sailed out to sea, only to surface on neighboring islands. Boards rescued, like humans, by the Coast Guard. Boards scooped up somewhere far, far away.

Three or four months passed, though, and Falter still had not found so much as a lead. Carlson, eventually, offered a deal—a deal that would seem to accept the fate of the light-blue beauty, and that would signify a pivot back toward the life Falter had so desperately wanted to leave behind. In exchange for a new board, the mechanic-turned-surfer/photographer would do some work on Carlson’s jacked Subaru.

The surfboard detective had come up empty, his search futile. Time, he figured, to move on.

***

At first, the fisherman thought he’d snagged part of a sunken boat, maybe some buried treasure. He brought the surfboard home and threw it in his yard—where eventually it caught the eye of the aspiring surfer next door. Branzuela saved up and in July 2019 offered to buy it. Perhaps he could defibrillate his dream. But fate would have to wait. The neighbor held out—no deal—before finally coming around a year later to ask Branzuela whether he was still interested. And just like that, after a small negotiation, the teacher who’d dreamed his whole life of surfing had finally snagged himself a ride, for just $40.

Branzuela hung the prize in his bedroom, weighing when and how he might actually learn to tame it. In bed one night, counting his blessings, he fixated on the elaborate elephant head design and it all felt like another nudge from the universe. He wondered whether he could uncover the meaning behind that head, how they came to be imprinted on his new board, and so he started some surfboard sleuthing of his own. The crest, he discovered, seemed to be the mark of a board shaper … which led him to Carlson. On Facebook, he sent a message, along with a picture of him holding the board on a beach.

An ocean away, Carlson could not believe the image on his phone, like a sign from the surf gods. No way, he thought, unable to suppress the deepest of laughter born from cosmic coincidence. The board he saw—the board that the fisherman had found and that the teacher had purchased—looked almost exactly like the one Falter had lost in the surf off Waimea Bay. He did a quick search. If it was true, this would mean the board had traveled something like … 5,000 miles? Across the Pacific? Intact? Not sinking into the abyss?

Carlson messaged his friend. “You’re not going to believe this …”

***

The story of the globetrotting surfboard spread across the world, landed on CNN, and raised some eyebrows. The lumber that washed up in the Philippines has a yellowish hue, not blue, and the elephant logos appear in photos to be spaced apart a bit differently—but Falter chalks this all up to differences in lighting and camera angles. (His pics are shot from higher up, Branzuela’s down low.) The discoloration can be accounted for by six months spent floating in the Pacific, under a scorching sun.

Carlson reminds skeptics, as well, that no two of his creations are exactly the same. When Branzuela sent a picture of his board’s belly, still inscribed near the fins with measurements and Falter’s name, all doubt was erased. The board in the Philippines was the very one that Carlson and Falter had taken to calling the Ghost.

All that remained was the most unusual Zoom call in a year of unusual Zoom calls, marking the latest—but not the last—step out of hundreds that bonded two strangers. Afterward, Falter and Branzuela kept in touch. Became friends. The surfer sent the teacher a YouTube clip (“Learn How To Surf in 10 Minutes”) and the teacher waxed the board, following the surfer’s instructions. In a world dominated by vitriol, where it can sometimes seem like everyone hates everything, two men with almost nothing in common came to know and better understand each other.

Eventually Falter learned that Branzuela had spent much of the year teaching on an island, unable to return home to his family because of pandemic restrictions. (Branzuela’s students need him now more than ever, he reasons.) And this sparked in Falter an idea. When all of this—imagine a hand, waved once, to encompass everything that has come of the past 200-odd days—is over, he will visit Branzuela in the Philippines. In the meantime, he’s started a GoFundMe page for his new friend’s school, and he’s shipped 200-odd pounds of books and other supplies to a bunch of kids who will take all the help they can get. Next he plans to send a haul of backpacks. “Sir Doug,” Branzuela says, “has a big heart.”

Falter must visit, too, though, because he must collect his baby and bring her home. In the Philippines, Sir Doug plans to teach the teacher (and his students) how to ride, establishing a small but meaningful surfing outpost at a tiny school he’d never heard of until recently, on the other side of the world.

A world that no longer feels so big or disconnected.