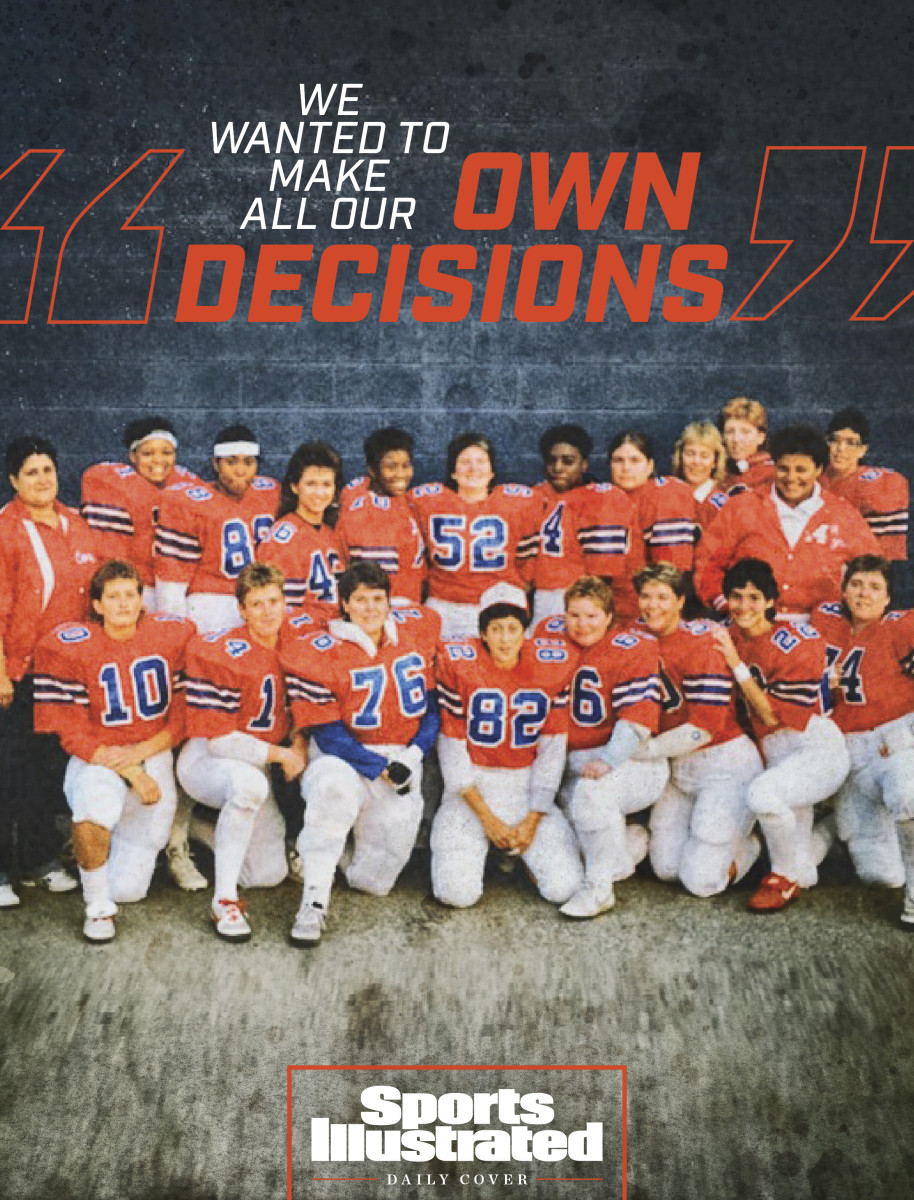

How One Women’s Football Team Took Control Away From the Men

Adapted from Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League, by Britni de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Arcangelo. Copyright © 2021. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

From her perch in the stands, Linda Stamps watched in disbelief as the game unfolded. A whistle blew, and women of all shapes and sizes, clad in jerseys and football helmets, ran plays, threw passes and tackled each other with reckless abandon. Stamps had never seen anything like it before, but she was already hooked; she wanted to learn everything she could about women’s football.

Stamps had been “football-crazy” her entire life. In 1973, she was a 23-year-old community organizer at a settlement house in Columbus, Ohio. A woman with feathered hair and round glasses nearly as large as her face, Stamps grew up in Lorain, about 30 miles west of Cleveland. It was a blue-collar steel town on Lake Erie. Growing up, the closest she could get to football was to play flute in the marching band, which at least put her on the field at halftime and in the bleachers during the games.

But that day, Stamps watched women play for the Cleveland Daredevils, owned by Sid Friedman, a Cleveland-based promoter who showcased beauty pageants and sideshow-like events. In 1967, he started a women’s team as a gimmick, a gridiron-centric version of the Harlem Globetrotters. He quickly realized, though, that women who had been denied the opportunity to play the sport wanted to play real football. Sensing an opportunity, he pivoted and started an unofficial league with other women’s franchises to compete against each other.

By 1973, Friedman had four teams, three of them in Ohio. After Stamps watched the Daredevils play, she approached Friedman about her desire to start a team in Columbus. Friedman liked the idea and said he would provide uniforms. Stamps put out an announcement to the press and held a meeting for interested athletes. They decided to call the team the Columbus Pacesetters, a name that, in retrospect, Stamps admits was pretty long to print on uniforms and pretty hard to fit into a cheer.

Working with Friedman was difficult. Before the 1973 season started, he’d lost his most prominent team, the Toledo Troopers, because the coaches and players were sick of his antics and looking to take themselves more seriously than they felt Friedman would allow. At one point in his women’s football venture, Friedman imagined tear-away jerseys and miniskirts, and he once sent a Hustler photographer to the team’s practice. “He wanted the carnival,” Stamps explains.

The last straw: Friedman asked the Troopers to throw games because he didn’t think a single, dominant team was good for business. When they refused, Friedman retaliated by refusing to let the Troopers play any of his teams, leaving them few potential opponents.

Still, Stamps loved the game so much that she wouldn’t be deterred by Friedman.

“The experience of executing one play when all 11 players do what they’re supposed to do with your position is like choreography,” Stamps says. “It is a beautiful experience. A lot of folks feel like, ‘Oh, it’s such a violent game and it’s for the feminists’ and all this, but it’s a magnificent game. And women didn’t have access to it.”

Stamps didn’t build her team alone. Her softball teammate and organizing comrade, 29-year-old Paralee Adams, along with about 20 other women, put together the foundation. Adams had grown up near the west side of Columbus and was slightly older than many of the other players. She was married with two children, and one of the few Black women playing on the team. Her husband, Karl Adams Sr., was a former tackle for Bluefield State, and he worked with Adams on some of her game’s weak points on weekends. Karl joined the coaching staff for a time to work with the line.

As Stamps continued to talk to Friedman about starting a team, she quickly became disillusioned. “He wanted us to turn football into faux wrestling, and we said no,” Stamps says. A Chicago Tribune story reported that Friedman would say crude things during timeouts of Daredevils games, like “someone’s bra strap broke” and “someone’s got to adjust her girdle.” His attitude toward all his players was concerned with publicity and image first and foremost, and football was secondary.

“We are athletes, and we consider ourselves athletes and we love this game,” Stamps says. They decided to part ways with the promoter. Friedman, for his part, wanted his uniforms back. He filed a complaint with the night prosecutor’s office in Columbus to force the women to return them.

Stamps then got in contact with the group of men who had purchased the Troopers after they left Friedman. Frank Wallace, a Detroit businessman, Troopers coach Bill Stout and a man named Harry Eschedor Jr. had formed a holding company called SKW Enterprises, Inc. It was chartered and dedicated explicitly to “the propagation of women’s football.” The board of directors included Eschedor, who was the chairman, along with Wallace, who was the secretary and treasurer, Bill’s brother Mike Stout and Bill Stout himself. Bill was a major stockholder in the company, and players signed yearly contracts and were listed as employees.

The Pacesetters moved under SKW’s ownership in 1974. Wallace served as the team’s general manager. That year, many of Friedman’s other teams joined forces with SKW’s teams and a few independent women’s football outlets around the country to form a single, unified group: the National Women’s Football League. It was the first official professional women’s football league in U.S. history and consisted of seven teams: the Los Angeles Dandelions, Toledo Troopers, California Mustangs, Dallas–Fort Worth Shamrocks, Detroit Demons, Dallas Bluebonnets and Columbus Pacesetters.

The team initially struggled to build a following, in part because it lacked a home field. Stamps spent much of her free time appealing to every middle and high school in the area, begging them to let the Pacesetters use their field. They moved around nearly every game, but they had a die-hard base of around 500 fans who could be counted on to show up no matter where they played.

For three years, the Pacesetters played about 10 games a season. They were a good team, winning about half of their games. Their biggest rivals were the Troopers, by far the best team in the league. Under the tutelage of Stout, the Troopers won the first league title and would go on to become the winningest franchise in pro football history, men’s or women’s. Star halfback Linda Jefferson would be named womenSport Athlete of the Year by Billie Jean King’s womenSports magazine in 1975. (“I remember the first time we played Toledo,” Pacesetter Mary Morrison says. “Linda Jefferson got the football. And she hit me so hard, I passed out.”)

To keep up with the Troopers, Columbus eventually recruited a man named Norm Richardson to come in as coach, who replaced the original men who had started with the team. Richardson knew, and was committed to, the players. Stamps met him while working at the settlement house; Richardson was a housing inspector who volunteered as a football referee in his spare time and had received All-State honors as a player on Ashland College’s football team.

With a coach who believed in them by their side, the Pacesetters were ready to take on the league.

And they didn’t know it yet, but this group of women would end up challenging the league off the field, too, wresting control of their team from the men who owned them and forming the blueprint for how many of today’s women’s football teams’ ownership groups are structured.

“The beauty of the Pacesetters,” Stamps said, “was that kids got to unlock all this gender nonsense.” Kids of any gender could come to a game and see a different path for themselves, whether it was on the field or on the sidelines. The Pacesetters were also the only NWFL team to have cheerleaders, who were mostly gay men.

In their first season, the team competed against Friedman’s Daredevils, winning 12–0 and handing Cleveland its first loss after going undefeated in 1973. Stamps, at 5' 6" and 130 pounds, played linebacker, while the 5' 2", 118-pound Adams played both ways as a running back and defensive back.

Columbus was home to Ohio State, which meant the pool of potential players skewed younger than in some of the other league’s cities, with many of the women who came out for the Pacesetters being college students. One was Morrison, a 21-year-old who had just graduated from OSU and was working as a driver for the United Parcel Service. A soft-spoken brunette with broad shoulders, she had moved away from her hometown of Monassen, Penn., for school.

Morrison, a halfback who was the Pacesetters’ best player during her time on the team, carried the ball a total of 208 yards in the team’s first three games. She tried out with her girlfriend at the time, Rose Motil, who served briefly as the team’s quarterback before a knee injury sidelined her.

Being near OSU also meant there was a built-in fan base for football—the sport was king in Ohio—but even more built-in competition. To find fans and make their appeal broader than that of the Buckeyes, the Pacesetters marketed themselves as “family-friendly entertainment”: A ticket to a Pacesetters game cost about the same as a ticket to the movies. The college football game atmosphere was often filled with unruly male fans spewing obscenities, alcohol and raucous crowds. At a Pacesetters game, many women and children joined their male family members in filling the stands to cheer on their friends, sisters, mothers and local athletic heroes.

But billing themselves as “family-friendly” meant that there was a part of themselves they had to keep under wraps: Many of the women who played for the Pacesetters were gay. They frequented Columbus lesbian bars like Summit Station and Mel’s, and a lot of players discovered the team through word-of-mouth there. In cities like Dallas, the local women’s bars bought ad space in the game programs of their NWFL team—the Shamrocks. The Pacesetters felt that wasn’t an option for them.

“Summit Station would have bought an ad,” Stamps says. “We were homophobic enough ourselves in the sense that we did not do it because we were afraid it would destroy everything, that we wouldn’t be able to sell one ticket.”

The players may have been quiet about their associations with the gay community, but they weren’t shy about openly associating with feminism and the women’s liberation movement. For many of the other teams in the league, the second-wave feminist movement didn’t resonate, and most players were clear they weren’t playing football to make a statement. But the Pacesetters were different: Their logo was the “female” symbol with a football player running through it. Part of this likely had to do with the number of OSU students who played and their access to feminist theory in school. Many of the players on other teams were slightly older or were already working in trades. The day-to-day reality of their lives didn’t leave them time or interest to engage with theory or organizing movements.

Julie Sherwood, who practiced with the Pacesetters before going on to become their longtime trainer, said she discovered the newly formed women’s studies department during her time at OSU, giving her language for her personal experiences. And even if there were players who wouldn’t have used those words to describe their time on the gridiron, playing on the team was “kind of the feminist thing to do.” Even still, Sherwood acknowledged that openly admitting to being a feminist at that time “was to condemn yourself to be trivialized”—something Sherwood saw the media and others attempting to do when they explained away women’s football as nothing more than a political statement. One headline about the team mocked their skills, proclaiming that “pacesetting comes later” and declaring them “a social club with pads and cleats.”

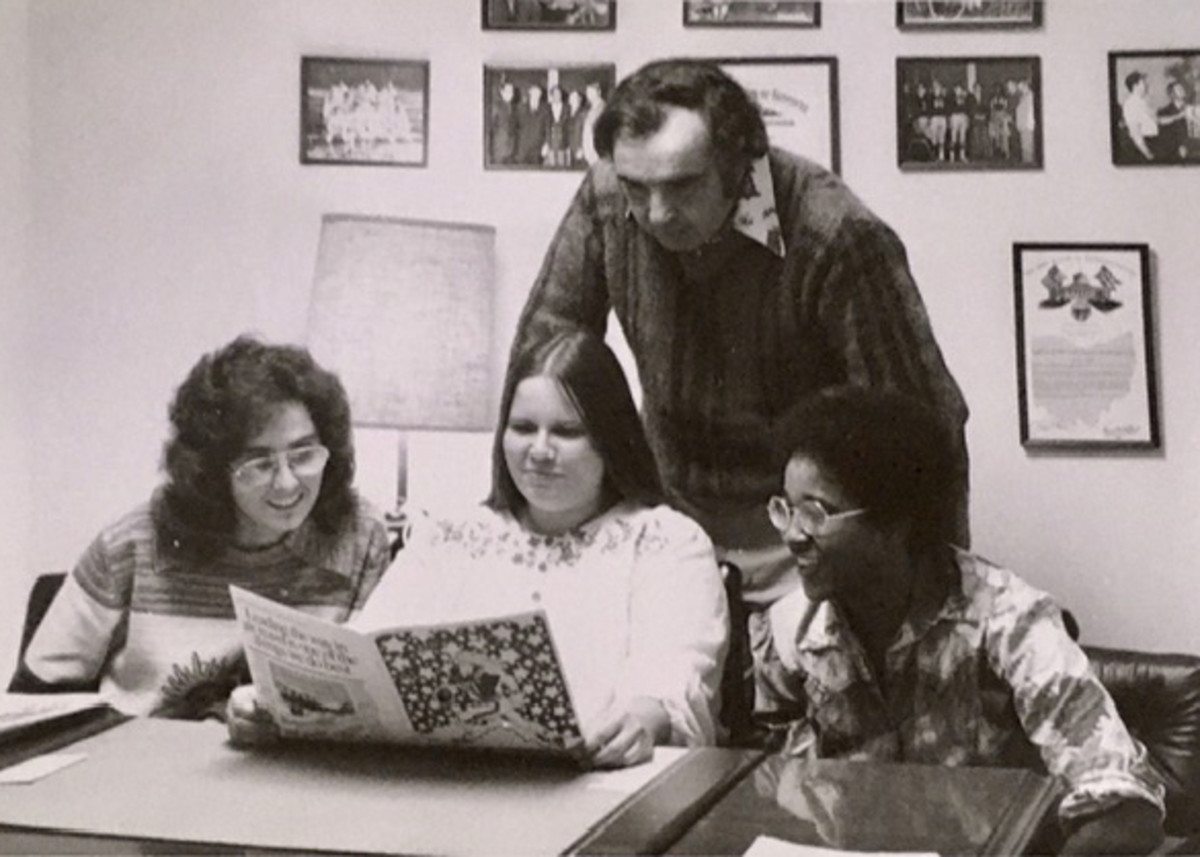

The Columbus chapter of the National Organization for Women wrote letters to the local press on the team's behalf, complaining of their sexist coverage. In one 1975 letter to the chairman of the department of journalism at OSU, Erica Scurr, Columbus NOW’s president, took aim at an article that ran in the Ohio State Lantern, the school newspaper. The article featured a photo of a player on the field whose jersey had ridden up during a play, exposing her bra, alongside the headline, “Women’s football: no ‘pansies’ wanted.”

“It is unjust to portray [the players] as big dumb broads with masculine attributes and desires,” Scurr wrote. “Such portrayal serves to intimidate and discourage other women who, while anxious to enjoy the benefits of sporting activities, are reluctant to associate themselves with this stereotype and suggests sexist attitudes and manipulative tactics no longer appropriate on an inovative [sic] campus committed to equal opportunity for women and men.”

The battle for equal treatment wasn’t just playing out in the media. It was being fought behind the scenes, too. The Pacesetters may have been billed as a feminist utopia, but men were still running the team.

While they were satisfied with the coaching and the team itself, Stamps, Adams, Morrison, and the rest of the Pacesetters quickly grew frustrated with SKW’s ownership. Not only did they feel like they were not prioritized in the way the championship Troopers were, but they were also put off by the ambivalent tone that came with communications from the corporation, accusing SKW’s correspondence of having the “cold, impersonal attitude demonstrated by large conglomerates such as General Motors” (potentially a dig at the Detroit-based members of the ownership group).

One example was a 1975 letter from SKW, which was addressed to Stamps and Adams as the player representatives and co-captains of the Pacesetters, discussing the need for an outline of player rules. Wallace wanted to have one that could be easily referenced if any player complications arose. But the manner in which he discussed the need for player rules was condescending, and some of the rules he suggested were controlling—such as a dress code for both away and home games, where players were expected to wear “respectable clothing, clean, pressed and in good taste” and not “ragged T-shirts or turned wrong-side-out sweatshirts or blue jeans with holes in them.”

Stamps also tried to renegotiate her player salary, which was a mere $12 per game ($67 in today’s money), ahead of the 1976 season per an addendum and notation in her ’75 player contract. She wrote a professional and polite letter to Wallace addressing the matter, but it was never resolved.

The board of directors at SKW replied to Stamps and Adams, apologizing for the “lack of sensitivity” and “misunderstanding” regarding the tone of the renewal contracts, attributing it to the fact that they were “rather new” at “planning and directing the needs” of the corporation.

But the women of the Pacesetters had had enough. They were ready to do something about the way they were being treated. The decision they made next, the one in which they took matters into their own hands, wasn’t necessarily intended to be a political statement. However, because of their history, the players believed they had power and that, together, they could leverage it. Football taught them that, too.

“One of the things many of us loved about the game is the sense of ‘power over’—you tackle someone, take them down,” Stamps says. “You don’t get that experience anywhere, metaphorically or in real time. As a woman, you’re normally sitting there with your legs crossed, waiting for the next pinch on your ass.”

The women who started the team had met through organizing for housing justice, and they brought their activist roots to the table when they decided to band together and purchase their team from the corporation of men who owned them. As a team, the players no longer wanted to be under SKW’s thumb. “We wanted to own ourselves; we wanted to make all our own decisions,” Stamps says. “It wasn’t a falling out. It wasn’t a hostile thing.”

They sent several letters of grievance laying out their complaints before ultimately forming Ohio Professional Athletes, Inc. (OPA) in 1977 with the intent of purchasing the team themselves. They also met with the NWFL to discuss the matter at the league’s annual meeting and received their full support. The only issue that remained was coming up with the money, as SKW was asking for $2,500 in cash for the sale as well as the coverage of any legal fees not to exceed $300. In return, the players would retain the Columbus Pacesetters’ name, equipment and all current player contracts.

Stamps, Adams, Morrison, coach Richardson and Susan Barney, Stamps’s longtime partner who worked at a law firm and had been serving as the team’s business manager, each put in $100 to incorporate OPA. But it wasn’t enough. The Pacesetters had to get creative as the deadline for the sale loomed. They then came up with the idea of selling common stock at $10 per share and advertised it by inviting folks to “own a piece of the pigskin!” Stamps remembers her dentist buying some, and giving talks around town encouraging others to do the same. There wasn’t any formal advertising, and the scheme spread mostly through word-of-mouth. Many members of the gay community chipped in, too, creating the sense that the Pacesetters’ entire community were banding together to support their team.

It worked. And that’s how the team funded itself, alongside ticket and concession sales and selling ad space in their programs, and began the 1978 season well on its way to being a fully player-owned team. “I am sure we will have a better crack at determining our own direction by building our strengths, eliminating our weaknesses and backing a winning team,” Stamps told the Marion Star in ’77.

The move by the Pacesetters to buy their own team fit into a larger theme of NWFL players trying desperately to self-determine. The Demons players had wrested control of their team away from Friedman to join the NWFL when it launched, giving them the ability to dictate how the team would be run. But it came at great cost to the players; in 1975, even with a team budget of just $15,000, they lost $4,000. The next year, they operated on a $24,000 budget—one player put $8,000 of her own money toward that, while quarterback Bea Guzman threw in $6,000. They ended up losing $13,000 that season, even though it was their first with a winning record and five dedicated coaches on board to help them improve.

The Houston Herricanes, who formed in 1976, had always been player-owned, but it came at the expense of financial support or security. In the ’80s, a former Demon named Mary Lohrstorfer owned teams in both Battle Creek and Grand Rapids (and later, Lansing), single-handedly financing the NWFL in the state of Michigan through car washes and T-shirt sales. Stout and a bunch of other men had been in control of the Troopers’ financial situation, making those players subject to the whims and decisions of their male owners.

It was the women on the field who set the records and won the championships. But they never saw any financial benefit from their talent. And they lacked even the agency to be able to make decisions about how the team would run—or when it would end.

Buy Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women's Football League

The Pacesetters were the longest-running team in the league—the only one to play from its inception in 1974 to its demise in ’88. Both Stamps and Morrison left after the ’77 season. Adams transitioned into a coaching role, making her likely to be the first woman to ever coach professional football. The NFL currently boasts a record 12 women coaching in the league during the 2021 season, all of whom stand on the shoulders of Adams. OPA went into the hands of Andie Dameron, a player who nearly single-handedly kept the team going for the next decade.

The Pacesetters finally beat the Troopers, becoming NWFL champions in 1979—after Jefferson retired, and after Stamps and Morrison had stopped playing. They stayed atop the league until ’82. By that point, most of the teams had folded, leaving only a few in the Rust Belt region still playing. By ’88, society was a different place than it had been a decade before. In the Pacesetters’ 15th-anniversary program, there is a full-page ad toward the back: “Summit Station supports the Pacesetters!” it read.

After 14 years with the team, Dameron took over coaching in 1988. By that point, all three of the team’s coaches were former or current players: head coach Dameron; Tina Adams, who joined the team in ’77; and Lore Thompson, who both played and coached that year.

The lack of infrastructure for the women who played in the NWFL showed on the football field. Most of the players essentially learned the game in their early 20s and 30s. As a result, the skill level between teams in the league was incredibly skewed—some were great and had natural athletic skills to fall back on; others were awful. While the quality of coaching was a factor in the disparity between teams, some of it was just luck. The teams drew participants from whatever pool of players showed up for the tryout in their location. Some teams were forced to take lesser-skilled players simply to fill out their roster.

In a 1975 article in the Columbus Citizen-Journal, reporter Sharon Abercrombie wrote that the team was coached by men “only because women haven’t been with the game long enough to learn the technicalities of coaching.” Adams’s transition into coaching in ’78, and the players who followed in her footsteps, are evidence that this is true. They demonstrate how important it is to have a development pipeline to create opportunities at all levels and in all positions of the sport.

While more girls are playing youth football than ever before, with nearly 2,500 participating in 2018, there is still no feeder system at the youth or high school level for women’s football. Often, like their NWFL predecessors, women are learning the game as adults by joining one of the four semipro leagues around the country. Women in Columbus have still not given up the dream of playing pro football. A new Women’s Football Alliance team is preparing to launch for the 2022 season: the Columbus Chaos. But the challenges that the Pacesetters faced remain.

The NWFL’s lack of an official draft to facilitate spreading talent around the league is mirrored today in the WFA, where some teams are dominant—like the Boston Renegades, who were the subject of a recent ESPN documentary—and others are on the fringe. And these teams are still self-funded, scraping for sponsors and paying to play the game they love.

The Pacesetters’ story is one of resistance that is relevant today when it comes to the way women athletes are still trying to gain agency, power, and investment for their leagues. We see it happening with the National Women’s Soccer League, with players demanding better from the league, its team owners and its coaches. We see it happening in the Women’s National Basketball Association, where players used their voices and platforms to enact positive change within the league via a new collective bargaining agreement, increasing player salaries and benefits. And we see it in the National Football League, where more and more women are becoming part of the fold as coaches, scouts and team owners.

At the time the Pacesetters set out to carve their own path as a legitimate and independent football team in the NWFL, they didn’t realize the significance of their actions both on and off the football field. No one did, not even their coach.

“Tonight will present to you one of your few chances in life to be truly great,” Richardson told his team one night before what Stamps suspects was a game against the Troopers, in an attempt to make believers out of a team that had never beaten Toledo.

“No, your name will not go down in history,” he continued. “No, the newspapers will not relive this night 50 years from now. No, there will not be a book or movie about tonight.”

About that, he was clearly wrong.

More SI Daily Covers:

• Ode to the Disappearing .500 Season

• How Long Can We Play? The Quest to Prolong Athletic Mortality

• The Little Blessings of the Black Widow, Jeanette Lee