Who’s Still Got Milk?

Strength comes in many forms and has many sources. But what does it mean to be strong? We have a few ideas. Check back throughout the week for more.

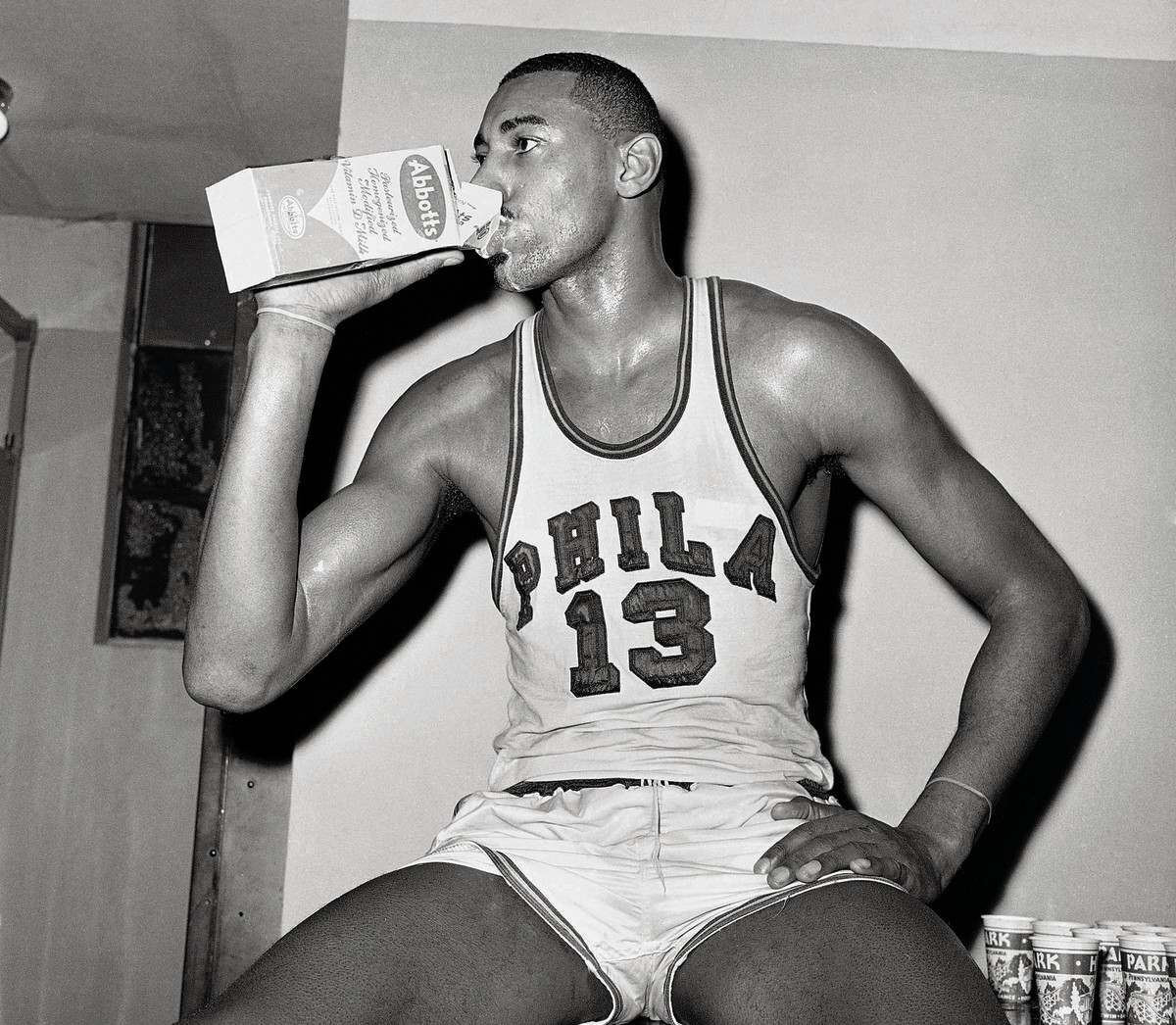

Wilt drank milk. Immediately after he scored 100 points in an NBA game, Wilt Chamberlain toasted the feat with a tall drink befitting a tall man. In the Warriors’ locker room in Hershey, Pa., he reached not for beer or champagne or whiskey but something more suitable to his godlike stature: a half gallon of Abbotts Pasteurized, Homogenized, Modified Vitamin D Milk, which he chugalugged straight from the carton.

Below his real mustache, a milk mustache blossomed. It formed a headwater that fed a streamlet that drained onto the delta of Chamberlain’s chin. And still he guzzled. Wilt, at the time, drank a quart and a half of milk a day, often without pausing for air. On summers off from Overbrook High School in Philadelphia, Chamberlain worked as a bellhop at Kutsher’s resort in the Catskills, where he fortified himself with milk, draining cartons “in one gulp,” as owner Helen Kutsher put it. The Dipper was not a sipper.

Chamberlain was the tallest and most powerful athlete of his time, a 7' 1" man who could deadlift 625 pounds. On that historic night of March 2, 1962, he stood in the locker room as the ultimate proof of what parents had been telling their children for decades in American life: Milk will make you grow big and strong.

Milk is still pasteurized and homogenized, as Chamberlain’s carton boasted, but it’s also been lionized and demonized, canonized and eulogized, weaponized and publicized. Got Milk? Milk has left society in general and sports in particular polarized. “It has been argued about for at least the past ten thousand years,” writes Mark Kurlansky in his 400-page history of milk called Milk! “It is the most argued-over food in human history.” Former Cardinals, Titans and Lions defensive end Kyle Vanden Bosch drank two gallons a day in high school. Vegan athletes like Cam Newton and Kyrie Irving won’t touch it with a 10-foot crazy straw.

Pasteurized, Homogenized, Modified—and Marginalized: Wilt’s greatest moment also marked the last great peak for milk, whose consumption in America, by 1962, had already been in decline for 10 straight years. Milk consumption in the U.S. has now been in decline for 70 consecutive years. In ’84, the makers of Wilt’s celebratory tipple, Abbotts Dairies of Pennsylvania, filed for bankruptcy and put its fleet of milk vans up for auction after 108 years of delivering dairy products to Philadelphians. That city’s milk chain of supply once included Wilt Chamberlain, who, as a six-year-old, worked for the milkman in his west Philadelphia neighborhood, collecting empty bottles. One might argue that Chamberlain himself was a dairy product. A study published last year in The New England Journal of Medicine found evidence that milk consumption in childhood does promote greater height.

The Milky Way was named for the Greek goddess Hera, who pulled the infant Hercules off her breast, spraying life-giving milk across the heavens. Wine may be the nectar of the gods, and beer the lubricant of the bleacher masses, but milk was—and sometimes still is—the maker of stars.

From the beginning of sports, cow milk was the GOAT milk. Ted Williams, as a prospect, was fattened up with milk and milkshakes. He drank two quarts of milk after most Red Sox games. Williams’s finest year was also milk’s. Nineteen forty-one, when Williams batted .406, was the peak year of milk consumption in the U.S., according to the Smithsonian Institute of American History. That year, Americans drank, on average, 744 glasses per person, thanks to advances in refrigeration, sterilization of bottles and relentless ads like this one in Maryland: “Sometimes young men between 16 and 20 get the foolish idea that milk is a sissy drink. Of course, if they were to see the training tables where husky football players eat, they would soon change their minds. Purity Milk, with its high butter-fat content [and] abundance of vitamins, calcium and phosphorous is what helps build those strong muscles the ‘gals’ admire.”

Has any animal given more to one sport than cows have to baseball, covered in the hides of Holstein cattle, caught in leather gloves made of tanned cowhides, by men who claimed to be fueled by cow’s milk? When the Pirates clinched the NL East division title in 1974, players poured a gallon of milk over their manager, Danny Murtaugh, because he was a teetotaler, and milk was often used as a chaste substitute for alcohol, especially (as we shall see) in championship celebrations.

Milk and alcohol do mix on occasion. The winner of the first marathon in the modern Olympic Games, Spyridon Louis of Greece, drank milk and beer and wine in the hours before and during his triumph. Bob Drum, the late and legendary golf writer for The Pittsburgh Press and occasional CBS essayist, enjoyed a glass of milk with his hard liquor, a ritual he called foaming the runway. It’s a technique that had its proponents among athletes.

“After we won the Western Conference title, Wilt and I went out drinking,” Chamberlain’s Warriors teammate Tom Meschery told Terry Pluto, author of Tall Tales, an oral history of the NBA. “Wilt was not one to drink. Being Russian, I thought I was a great drinker. Well, Wilt said he would drink me under the table. We went to a bar in New York. He ordered about 10 Scotches and milk. That’s right, he drank Scotch and then a milk. He hammered them down, one after another. I tried to match him drink for drink, but the last thing I remembered was being face down on a curb on Broadway with a cab coming about an inch from running me over. From what I understand, the ten drinks didn’t even touch Wilt.”

Of course they didn’t. The Dipper had been foaming the runway.

Indy 500 winners have celebrated with a bottle of milk almost without pause since 1956, when Big Milk began offering a cash prize to the champion. Drivers are now asked in advance of the race their preference for whole, 2% or skim, which they drink in Victory Lane from a bottle provided by American Dairy Association Indiana, Inc. When Brazilian driver Emerson Fittipaldi drank orange juice before his milk after winning in ’93—he owned a 750,000-tree orange grove—he had to issue an abject apology at pitchfork point. It included the phrase: “I deeply regret the misunderstanding and inconvenience I caused for the American Dairy Association.”

It wasn’t enough. That summer, Darrell Waltrip told a cheering crowd while promoting Nascar’s inaugural Brickyard 400 at Indy: “I’m an American, and if I’m standing on this spot next August, I’ll be proud to drink a bottle of All-American milk.”

Read More From SI’s Strength Issue

Milk was long a symbol of American goodness. “Uncle Sam wants you to drink more Dierolf’s milk,” as an ad put it in 1929. The message still resonated nine decades later, when a boy named Brady asked Michigan football coach Jim Harbaugh how much milk he should drink to grow up big enough to play quarterback. “As much as your little belly can hold,” Harbaugh replied.

Harbaugh prefers whole milk to the “candy-ass” lower octanes and once posted a photograph of himself at Ruth’s Chris Steak House in Ann Arbor, Mich., about to tuck into a steak the size of a second-grader’s backpack. In the foreground, to wash it down, was a water glass full of whole milk.

But even Harbaugh is a lightweight compared to Manute Bol. Heir to Chamberlain as the NBA center in Philadelphia, Bol exceeded the Dipper in two important, possibly related categories: at 7' 7", he was nearly a half foot taller than Wilt, and he drank even more milk. A single gallon of milk was an aperitif for Bol. As a teenager in Sudan, Bol was sent to “milk camp” in an unsuccessful bid to fatten him up. There, he drank milk from May to September with other teens. He drained cows dry. Even as an NBA player, Bol could drink three gallons of milk in a day, though he remained, obstinately, whisper-thin.

Bol existed in a long, milk-intensive continuum of Philadelphia centers. Between Bol and Chamberlain was Moses Malone, who was allowed to play pickup hoops at Petersburg State Penitentiary in Virginia as a high schooler, honing his game against a person called the Milkman. When Maryland coach Lefty Driesell asked Malone why he was called the Milkman, Malone famously replied: “Because he murdered a milkman, man.”

Beware of Sutters wielding udders. North American sports have a long tradition of athletes who grew up milking cows, including the seven Sutter brothers, six of whom went on to play in the NHL. As children, the Sutters of Viking, Alberta, turned cow teats on one another, squirting milk in the eyes of unsuspecting siblings, in Cain-and-Abel meets Moe-and-Curly fraternal warfare. “Sometimes there was more milk on the ground than there was in the can,” said Duane Sutter, who played 11 years for the Islanders and Blackhawks, knowing a cheap shot could come from any angle.

Likewise, Tom Brady’s mom, Galynn, grew up on a farm in Browerville, Minn., and the future seven-time Super Bowl winner milked cows there on summer visits. He was told by his grandfather Gordon when missing the bucket: “Hey, that’s money you’re squirting around.” Brady seldom again squandered natural gifts. (Though, nowadays, he wouldn’t be caught dead around a dairy product of any kind.)

Elle Purrier milked cows before school on her family’s dairy farm in Franklin County, Vt., and when she didn’t finish her milk at dinner, Charlie and Annie Purrier told their daughter that the cows knew and were disappointed. The next morning, Elle felt the cows looking at her funny. “That really did the trick for me,” says the 27-year-old, in Flagstaff, Ariz., where she’s altitude training as one of the world’s premier middle-distance runners. Competing under her married name, Elle St. Pierre, she was the silver medalist in the 3,000 meters at the world indoor championship in Belgrade, Serbia, in March, and is the U.S. record holder for the indoor mile (4:16.85) and indoor two-mile (9:10.28).

As a 4-H kid, St. Pierre had a blue-ribbon show cow named Bessie, whom she showed at fairs in middle school. As a high school freshman, Elle was discovered by Richford High track coach Richard Flint while annihilating her teammates in a timed mile in freshman basketball practice. Richford cross-country coach Andrew Hathaway encouraged Elle to equate dairy farming with running: The cows need to get milked three times a day, he said, and so it was with training.

It’s early afternoon in Arizona. St. Pierre has just had a glass of milk after her workout. She is training, long term, for the next two world championships and, beyond those, for the 2024 Paris Olympics. “No matter where I am in the world,” she says, “one of the first things I will do is go to a store and get single-serving chocolate or strawberry and sometimes just normal milk. It’s a quality product that a lot of hard work and passion have gone into making.” The same is true of her running. The athlete and farmer are one; the miler and milker are indivisible.

If our modern Milk Nation had a flag, it would look like Neapolitan ice cream: bars of brown, white and pink, representing the primary flavors of the milk lover’s palate. Chocolate milk is by far the most popular milk among athletes now, offered as a postworkout recovery drink in locker rooms everywhere. Few Americans are as farm literate as St. Pierre. In a 2017 survey, 7% of Americans thought chocolate milk came from brown cows.

Strawberry milk has its proponents, most prominently Seahawks receiver D.K. Metcalf, who quaffed it while maintaining 1.9% body fat at Ole Miss, drank it after running a 4.33 at the NFL combine, rocked it in the form of strawberries on the lining of his draft day jacket and wore a Nesquik medallion as a rookie. (Inevitably he now does commercials for the brand.)

Some still take their milk straight, though—and some straighter than others. Cardinals quarterback Colt McCoy, who grew up on a dairy farm in Texas, made headlines for drinking unpasteurized “raw milk,” making Harbaugh’s whole milk look candy-ass by comparison. “I think it’s right out of the teat,” said McCoy’s coach in Washington, Jay Gruden. “I swear, this guy’s a nut job.”

Lactose intolerance often sets in with age. Michael Phelps, who drank chocolate milk at his first Olympics, in Athens in 2004, appeared in ’20 on cartons of Silk soy milk and confessed to mixing almond milk into his smoothies.

Sports have reflected society’s shift. In 1970, Cubs fans could buy a carton of Borden’s milk for 20 cents at Wrigley Field. Last year, in the same park, the Cubs offered dairy-free soft-serve ice cream from a Swedish oat milk company. Plant-based milk is proliferating like kudzu. Just gaze through the looking glass of your grocery “dairy” case. For vegans, the lactose intolerant, the milk-allergic or the calorie-counting, there are cereal-, seed-, nut- and legume-based milks, including oat, soy, almond, hemp, coconut, rice, pea and quinoa milks. To paraphrase Exodus, ours is a land flowing with almond milk and buckwheat honey.

Milk consumption in the U.S. declined by an average of 1.0% in every year of the first decade of the 21st century, and by an average of 2.6% in every year of the 2010s, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Even the Purriers sold their milkers in December ’20, a milestone that remains so upsetting to St. Pierre that she finds it hard to talk about even now. But she also thinks our tsunami of milk substitutes will not permanently supplant ancient milk, a river that connects human beings to their earliest ancestors.

Milk isn’t just Biblical, after all, it’s Shakespearean. Lady Macbeth spoke of “the milk of human kindness,” suggesting milk is warmth and goodwill in beverage form. “There isn’t milk on the table every night like there used to be,” says St. Pierre, “but I kind of feel it will come back around.”

The Milwaukee Milkmen are an independent minor league baseball team in Franklin, Wis., whose logo bears a 1950s-era milkman in bow tie and peaked cap. Their fans really are mooing, not booing, when prompted pregame to low like a cow. The milkman mascot, Bo Vine, wears 2% on his jersey and fans can choose, at the concession stand, between chocolate and regular milk. As a nickname, Milkmen won out in 2019 over Crop Dusters, Cow Tippers and Haymakers, suggesting a yearning to fill some metaphorical calcium deficiency, at least in America’s Dairy Land.

Even so, Milwaukee’s most famous milk man is still Bucks star Giannis Antetokounmpo, a longtime lover of Oreos, who just this past season discovered the joy of dunking those cookies in milk. Of his epiphany, the Greek Freak said: “I was like, What the hell? No freakin’ way, bro. This is amazing.” Milk and cookies instantly became, he claims, “an every-night snack.”

What could be more comforting than a bedtime treat of milk and cookies? For Giannis’s predecessor as MVP of the league, Chamberlain, milk remained comfort food his whole life. And while Chamberlain would eventually become more famous for other appetites—famously claiming to have slept with 20,000 women—he never lost his thirst for milk. Thirty years after his 100-point game, the man who had a waterbed built into the floor of his Bel-Air home—which had a moated, swim-up living room—paid homage to his simpler, earliest but enduring passion: “Give me a peanut butter and mayonnaise sandwich and a glass of milk,” he wrote, “and I am in hog heaven.”

Read More Daily Covers:

• ‘Oh, You Look Like the Rock’: Finding Rocky’s Family

• Kelly Slater Won the Super Bowl of Surfing at 50. So, What’s Next?

• NBA Draft? Nah. He’s Following the Money, Right Back to School.