What Does It Mean to Win at Saving Lives?

The first thing you will notice at a competitive lifesaving meet are the dummies.

Bright orange, they lurk at the far end of the pool, lying in wait until they can be reached and rescued by the swimmers. Known in the parlance of the sport as manikins, they may be inanimate, but they’re the main characters: These are the titular lives that need to be saved. Actual liveliness notwithstanding.

And if you have any questions, well, the second thing you will notice at a lifesaving meet is how difficult it is to ask for a good one. Because no matter how thoughtful—how reasonable the premise—any question about this sport sounds a little bit absurd.

Just how long have you been lifesaving? (“I’ve been lifesaving since I was a kid” sounds a tad weird, sure, but so does “I decided to try lifesaving two years ago.”) What did you think of the lifesaving out there today? (What did you think of the lifesaving out there today?!?) Or if you want to push the envelope a little: So … have you ever tried to save an actual life? (Fair, but: Come on.)

These are basic questions to ask of an athlete. But they’re awkwardly wrapped in the language of mortality: There’s simply no getting around the word “lifesaving” and all the weighty, existential baggage that comes with it. There’s a forcefulness here that’s absent from a term like “lifeguarding”—a similar concept, maybe, but a different connotation.

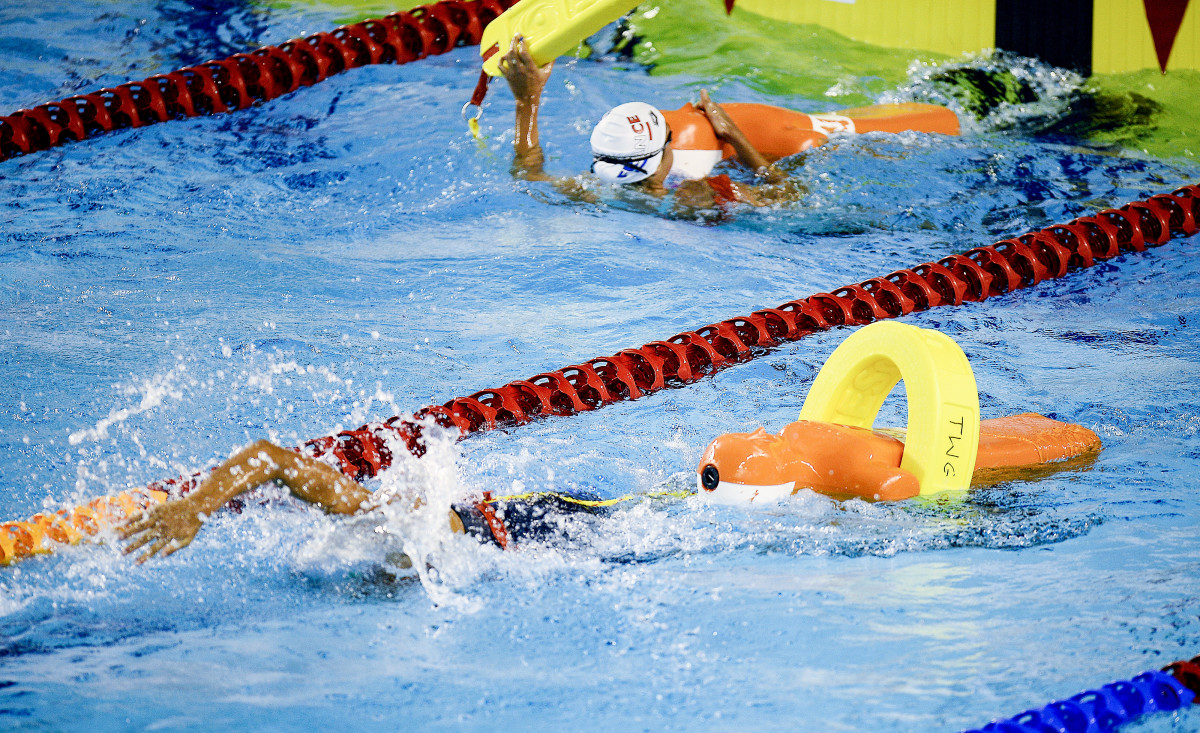

Yet for all the grand, important life-and-death spectacle that it implies: A competitive lifesaving competition looks quite a bit like a typical swim meet. Yes, there’s the manikin, which will be either carried on its own or towed with a rescue tube, depending on the event. There might be some flippers involved. (These are “fins” in lifesaving terms.) But to watch lifesaving in a pool is to watch something that looks very much like swimming, until it doesn’t.

All of which makes it an ideal representative of the World Games. Held a year after each Summer Olympics, this international competition is a venue for other sports, those that are less conventional or less popular or less global. It includes some that have their own history at the Olympics, some that want to have a future there, and some that seem far more suited for ESPN The Ocho. This July, the event returned to the U.S. for the first time since the inaugural World Games were held in California back in 1981. For two weeks in Birmingham, thousands of athletes competed in events including billiards, lacrosse, breakdancing, parkour, korfball, rhythmic gymnastics and tug of war. It was a showcase of what it means to define sports broadly. And even in that setting—positioned among the niche and the wacky—competitive lifesaving managed to stand out as particularly striking.

This is the edge of sports, yes, but it’s also a matter of life and death. Kind of.

The World Games has 16 medal events in competitive lifesaving: races of varying lengths, in different specialties, for men and for women. (Here, all take place in the pool, though other competitions feature open water and beach components.) But there is one particular race that ties all the different skills together—requiring competitors to save two manikins from different situations with and without gear. Welcome to the 200-meter super lifesaver.

The beginning could pass for an ordinary swimming competition: 75-meter freestyle with no fins, no manikins, no lives to save. This opening section is just about speed. But it soon gives way to a blitz of strategy and technique. First up? Rescuing a submerged manikin. At meter 75, each competitor must dive to the bottom of the pool to retrieve a manikin and—this bit is crucial—must bring it to the surface in the next five meters. (It only makes sense: Some lifesaving technique it would be to keep the life in question underwater.) The swimmers carry these manikins 25 meters. But once the swimmers reach the wall, those first manikins can be left behind, representing one set of “lives” “saved.” This is the halfway point. Now, the competitors must prepare to rescue the second manikin—which is floating instead of being submerged. For this one, they will use equipment rather than simply carrying the manikin themselves. Each swimmer has to grab a rescue tube and a set of fins from the edge of the pool. They get the gear on their person as quickly as possible and swim 50 meters to the opposite wall. There, a floating manikin awaits, and they must secure the rescue tube to the manikin, ensuring it is clipped on two places, and tow it the last 50 meters to the finish.

In essence: It looks something like a 200-meter freestyle race, if a 200-meter freestyle race included plunging to the bottom of the pool midway through, wearing flippers for the final two laps and, of course, saving two (symbolic) lives. It requires impressive swimming ability, but dexterity and strength, too. And speed is still of the essence. (For context: The men’s world record for the 200-meter super lifesaver is 2 minutes, 4 seconds, while the men’s world record for the 200-meter freestyle is 1 minute, 42 seconds.) There are countless details to nail down and fine-tune. There’s the plunge to get the submerged manikin and the dolphin kick to launch back to the surface. There’s the maneuver to slide their feet into their fins and the motion to clip the rescue tube to the floating manikin. That required attention to detail begins even before they get in the pool—competitors are highly particular about how they set out their fins and rescue tubes at the edge of the water.

Given all of this, it’s hardly surprising that some lifesavers joke they might have committed themselves to swimming instead, if only it weren’t so boring. Why swim when you can swim and lifesave? Once you’ve felt the adrenaline rush of diving for a submerged manikin—of slipping your feet into fins to power yourself toward a symbolic life to be metaphorically saved—why would you want to just swim?

Well, there’s the comparative ease of making a living, the chance of representing your country in the Olympics and the ability to say the name of your sport without generating double-takes. But what’s all that compared to the ability to call yourself a lifesaver?

The International Life Saving Federation is not a sports federation like any other. It establishes rules, yes. It facilitates participation at events like the World Games, where it has been a featured sport since 1985, and it runs its own world championship. (Held every two years, the next one will be in Italy in September.) It hosts a variety of commissions and committees that make decisions about competition. Yet because lifesaving is not a sport quite like any other, the federation naturally also has some, uh, additional work. There’s a hint in its name: While the sport is lifesaving, written as one word, the federation is Life Saving, split in two with its components emphasized as separate concepts. In other words—literally—the organization does not see its work only as governing lifesaving competitions. It also believes it is responsible for saving lives.

Or, as the federation describes itself in its mission statement: It aims to be “the world authority for drowning prevention, lifesaving and lifesaving sport.”

The grouping seems noble, if also profoundly weird. This is a federation that recently worked on a United Nations resolution to lower global drowning rates. It also made decisions about the right competitive field for a 100-meter rescue medley. Here is the critical, deathly serious real deal, and here it is as a game.

It reverses the modern popular movement to expand the definition of sports. That has generally come through events that may be less directly connected to the physical (esports) or less clear as objective competition (breakdancing) or simply less conventional. If there was ever a line between “sports” and “sports-adjacent entertainment,” it’s gotten awfully blurred now. Yet competitive lifesaving inverts all of these ideals—working backward from something highly serious rather than working forward from a place of whimsy. It’s highly physical, not just in the sport itself but in its concept: What is more physical than saving a life? It’s the oldest form of obvious competition—a straightforward race. And it’s fun only in spite of itself: There might not be an inherent conflict between entertainment and lifesaving, but at the very least, there’s a bit of friction.

The ILS Federation does not have its origins as a sports organization. Instead, it grew out of European rescue societies from the 18th and 19th centuries, such as the Royal National Lifeboat Institution in England and the Society for the Saving of Drowning Victims in the Netherlands. These groups’ mission was narrowly defined: to help save lives in the water. By the early 20th century, however, lifesaving competitions had started to appear. (There was even an unofficial demonstration of the sport at the 1900 Olympics in Paris.) The contests showcased early lifeguards trying out their skills against one another—mostly on beaches at first, but soon in pools, and eventually it grew into the sport as it looks today. (There are still open-water lifeguarding competitions—like the National Lifeguard Championships taking place in Hermosa Beach, Calif. this weekend—but organized meets in pool environments are the domain of competitive lifesaving.) This meant the original pipeline was straightforward: For people who had worked as lifeguards, who knew what it meant to save a life, it was simply a chance to apply their skills in a new way.

There are still many people who find the sport this way—who life save before they lifesave. This was the path for the current ILS Federation president. Before he went into administration, Graham Ford was a competitive lifesaver himself—his last major event as an athlete was the 2010 world championships in Egypt—and before that, he was a lifeguard. He still volunteers as a guard on the beaches of his native Australia. The work is important to him—the motivating force behind his involvement in the sport in the first place—and he can’t imagine ever giving it up.

“I love the camaraderie and friendship, but more importantly, the values of what we do,” Ford says. “Because we’re volunteers and we’re out there saving lives. That’s pretty special.”

He acknowledges there might be some peculiarities about rescue missions repackaged as competitions. But he sees it all in service of their larger goal: Every bit of attention on the sport brings awareness to drowning prevention, he says. Every lifeguard who becomes more invested in his skills because of the sport is moving a step toward global water safety. And every lifesaver who isn’t a lifeguard is still someone who’s far more equipped to save lives than he would be otherwise.

“This is what it’s all about,” Ford said after the final lifesaving medal ceremony at the World Games.

It was the standard language of an organizational leader after a successful event. And then he continued.

“What you’ve seen over the last few days is a simulation in the pool of what happens when we do rescues,” Ford explained. “But we do a lot more. We rescue people in lakes, in rivers, in the ocean.”

“I’ve been lifesaving since I was 3 years old.”

Marcel Hassemeier is one of the sport’s all-time greats. Though he’s retired now, he was on hand in Birmingham to be honored as one of the greatest performers in the history of the World Games. (His dominant effort in Colombia in 2013, with four gold medals and one silver, has become the stuff of legend.) He still looms large in the landscape of the sport, even in retirement, but it’s only fitting: He was born to it. Both of his parents worked as lifesaving coaches. This meant he was in the water from a young age. But although he showed early promise in swimming, including competing in youth national championships, he never considered a focus on anything but lifesaving.

“It’s more diverse than just swimming,” Hassemeier, who is German, said through a translator at the World Games. “The fins during the competition, the manikin to deal with, it’s way more diverse—it takes more effort and more skill.”

Unsurprisingly, Germany dominated the lifesaving scene during Hassemeier’s career. But the country has a long tradition as a lifesaving power—traditionally among the best in Europe, and globally behind perhaps only Australia, whose strong local beach culture means plenty of interest in lifeguarding—and that has continued in his retirement. This summer, Germany led the lifesaving medal count in Birmingham with nine gold and five bronze. (Italy led in overall lifesaving medals, with 17, though just two were gold.) Yet even with all their success, Team Germany’s effort was a reminder of just how narrow the margins for error can be in lifesaving.

The first slipup came in the women’s 100-meter manikin tow with fins. (Imagine the 200-meter super lifesaver if the race had only its second half.) One of Germany’s entrants in the race was 19-year-old Undine Lauerwald—among the youngest in the pool but already with a strong track record. She’d been part of multiple relay teams that set youth world records. And she’d been successful in her nascent adult career, too, winning bronze in this 100-meter event a few months earlier at the European Championships. Here, she got off to a quick start, clearly in medal position the whole time. But then came the moment of truth—the split-second maneuver needed to save a life. Lauerwald fumbled with the clip and failed to properly secure it to the manikin. Disqualified. Yet there was no time for Team Germany to dwell: The men’s race in the same event started just 10 minutes later. But they watched the same mistake happen again, this time from a lifesaver named Kevin Lehr, resulting in back-to-back disqualifications.

“We had a big success, but we also had those two misses,” German coach Kai Schirmer said afterward. “That’s lifesaving. You don’t only have to swim; you have to do all the technical stuff you need to save a life.”

In another body of water, in another context, these mistakes could have been the difference between life and death. In this pool?

Schirmer sighed.

“That’s our sport.”

• Aaron Rodgers Explains Why He’s Now at Peace

• She Kicked for Vanderbilt, and Then Things Got Hard

• ‘A League of Their Own’ Endures Because It’s Personal