The unknown trainer to the stars

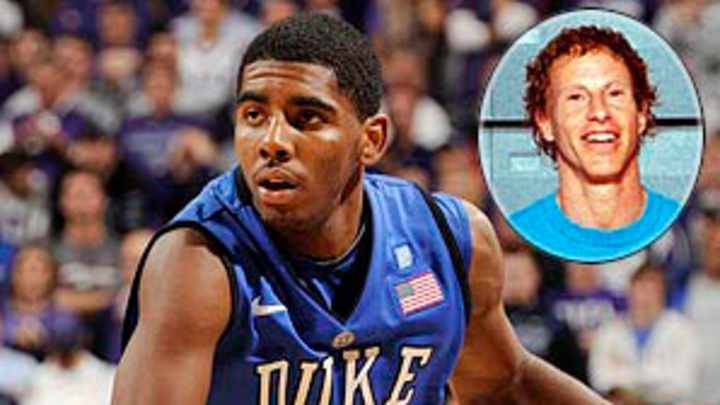

UNION, N.J. -- The first thing you notice when you walk into the tiny, nondescript gym is the mezuzahs, those tiny torah scrolls on the doorposts. There are no fancy scoreboards in the gym at the Young Men's and Young Women's Hebrew Association. No advertisements on the walls, not even new nets or rims -- just four baskets, a worn floor and a coach who has trained 32 NBA players over the last 35 years, including this year's projected No. 1 draft pick.

The community center, nestled between the monotonous drone of office parks and strip malls off exit 140 on the Garden State Parkway, is where Kyrie Irving's game was born. Randy Foye trained here before he starred for Villanova and was drafted seventh overall in 2006 by the Celtics. The Nuggets' Al Harrington was molded into the No. 1 high school player here. NBA veteran Dahntay Jones used to commute 2 ½ hours every day from Hamilton, N.J., to play here. Bobby Hurley made his name on this court before he became a star at Duke. Hurley played more games for this coach than he did his legendary father.

The coach isn't bashful about his success. "I tell kids when they come in, if you want a Walkman and a bunch of shoes go somewhere else," he says. "If you want to be a pro, stick with me."

If there's an archetype for how a basketball coach should look, Sandy Pyonin doesn't fit the mold. With Bob Cousy short-shorts and striking reddish-yellow curly hair, Pyonin looks more like a mad scientist than a coach. His wiry 6-foot-frame often contrasts with the sky-scraping athletes he works with, but it doesn't stop him from ordering these players around like a drill sergeant. Jones, now with the Indiana Pacers, was stunned the first time he saw the legendary coach. "He doesn't look like a basketball guy at all," Jones said. "I was surprised that this was the guy I had heard so much about."

Pyonin is a gym teacher at the Golda Och Academy, a pre-K-12 small Hebrew day school in West Orange, N.J. He also coaches varsity basketball at Golda Och, where his team has won two state championships despite being only able to practice one day a week because of religious obligations. His national reputation in the increasingly cutthroat world of high school basketball comes from his second team, the N.J. Roadrunners, a traveling summer-league basketball squad that has sent more than 300 kids to Division I programs. The Roadrunners have won three AAU national championships and are constantly competing with teams endorsed by shoe companies that recruit by throwing thousands of dollars worth of gear at teenagers.

Pyonin refuses to give his age. Based on estimates from his friends, he's somewhere around 60. Pyonin doesn't have a cell phone and only answers his home phone after 10 p.m. He has a fiancee (he's never been married) and a sister and enjoys billiards and the L.A. Dodgers. Everything else in his life revolves around a 29.5 inch orange ball. As Hurley, no stranger to the game, says, "Sandy is the ultimate gym rat. A basketball lifer. He loves what he's doing and that's all he cares about."

For a man who has spent his life teaching the intricacies of the game, it comes as a surprise that Pyonin didn't play basketball in college. He played soccer and lacrosse at Kean University, a Division III school only a stone's throw from the gym where he currently coaches. When he graduated, unsure about what he wanted to do with his life, Pyonin often wandered into the stands at the Y and watched St. Patrick's high school (now a national powerhouse) practice.

At the request of St. Pat's coach Bob Leonard, Pyonin eventually started handling individual workouts with some of the school's JV players. His teams were immediately successful and that's how the Roadrunners were born. Before the sponsored tournaments and national attention, the American Athletic Union revolved around two tenets: fundamentals and conditioning. Word of Pyonin and his grueling workouts quickly spread around New Jersey.

"We would play full court games, every basket was worth one point, to 100," Pyonin said. "No fouls, you have to play a physical game. I used to tell guys, if you're not in top condition you can't play for me. They got in shape quickly."

In his memoir, A Perfect Fit, former New Jersey Net Luther Wright recalls walking into Pyonin's gym for the first time. "I saw basketball being played as I had never seen it played before," Wright wrote. "It seemed as if everybody could dunk and block shots. I wasn't special."

Pyonin's first special pupil was Edgar Jones. By his own account, Jones was more an athlete than a basketball player. The 6-foot-10, 215-pounder wasn't sure if he was capable of playing basketball at the highest level. The first time Jones met his future mentor was during the summer after his junior year of high school at the Y. Pyonin challenged the talented teenager to a game of one-on-one. "We started playing and he was tough," Jones said. "He was physical and nasty; I was much bigger but didn't like playing against him." Under Pyonin's tutelage, Jones exploded his senior year. "I remember I got like 45 points and 24 rebounds in a game once and Sandy was screaming at me the whole time," Jones said. "I was mad at the time, but he was everything a basketball player needed. A guy who could get you to lift weights and run and do all that stuff you don't want to do."

After a successful senior year, Jones went on to have four standout seasons for the University of Nevada. He was drafted in 1979 by the Milwaukee Bucks but was cut the day before the season started. "Don Nelson [then coach and GM of the Bucks] told me I was too slow," Jones said. It looked like the end of the basketball road for the talented big man from Newark. "I had all but given basketball up," Jones said. "But Sandy kept coming. He kept telling me 'You don't know how good you are.'"

The pair started working out again at the gym in Union. They would start at 11 every night and go until 2 or 3 in the morning. Afterward, "we would either go to White Castle or drive around in my car for a few more hours," Pyonin said. On these rides, the young coach and former phenom would talk about everything from basketball, to girls, to their aspirations in life.

By the fall of 1980, the New Jersey Nets were looking for a big man and found Jones right in their backyard. He would go on to play five seasons in the NBA. "Sandy is the most genuine basketball guy I've ever met," Jones said. "He prepared me for the league, both mentally and physically. It was his passion that pushed me to go the extra mile. That's why he's family."

For Randy Foye, Pyonin wasn't just a coach, he was a father. Coming from one of the worst areas of gang-ridden Newark with no parents in the picture, Foye was in danger of becoming just another statistic. As a 12-year old, Randy was shooting around at a local gym one day when a guy he'd never seen before invited him to play with Al Harrington, then the top high school player in America, and Jay Williams, who would go on to star at Duke.

Foye began training with Pyonin individually year-round and playing with the Roadrunners during the summer. The two would ride in Pyonin's beat-up station wagon from Newark to Union every day so Foye could train. When it seemed as if Foye wouldn't have the grades to get into Villanova, Pyonin arranged for a tutor to help him. "Sandy was all about me so I believed in him," said Foye, now with the Los Angeles Clippers. "I would give him attitude, talk about not wanting to play that day or study and he would just push me through it."

This persistence has stuck with Foye through his successful pro career. "It wasn't just about basketball with Sandy. It was about life," he said. "All the things we've gone through together, all the traveling, he's always been there."

Unlike many of Pyonin's players, Irving did not come from an impoverished background. His father, Drederick, a former standout college player and current bond analyst at Thomson Reuters, trained Kyrie when he was young. Irving was not a highly touted player coming into high school; he attended Montclair Kimberly Academy, a school known more for its Ivy League acceptance rate than its basketball program. Drederick sent Kyrie to train with Pyonin during his freshman year. "I didn't know anything about his reputation or anything like that at the time," Drederick said. "Sandy was the most organized of the AAU coaches. Plus, he picked Kyrie up every day, which was nice."

Kyrie remembers his first encounter with the man he would spend most of his high school summers with. "Sandy just had a lot of energy," he said. "The first time I met him he was running around all over the place." The two worked out daily for months on end doing everything from dribbling workouts to six-on-one games. For Drederick, it was a perfect match. "When you put together Kyrie's work ethic with Sandy's passion," Drederick said. "That's when you create something special."

By his junior year, Kyrie had transferred to St. Patrick's. His national profile had skyrocketed and many local AAU teams were in pursuit of the speedy point guard with uncanny floor vision. But Irving stayed with the coach who helped him get to this point. "I was loyal to [Pyonin] because he had worked with me for so long," Irving said. "Sandy was my biggest fan and my loudest critic."

The nagging question about Pyonin in some recruiting circles is why hasn't he moved up. Why stay in the creaky old Union gym when he could easily get college or pro jobs? Those close to him have grumbled privately about how some of his wealthy former players haven't pitched in money to help freshen up the old gym. But Pyonin, who doesn't care about money or possessions, has never complained.

Jones, the player who has known Pyonin the longest, offers a different explanation. "At the end of the day Sandy is a teacher, not a coach," he said. "He doesn't have to worry about doing conventional things with players to satisfy someone else. He gave up his time and money for us. That's why we all trust him so much."

Walking across the floor Pyonin makes his presence felt. Pyonin is constantly in motion, barking various directives at different players. He still plays one-on-one with almost everybody he coaches, though he says he stopped playing with Kyrie after his talented pupil complained that he was hitting him in the face too often.

The court is filled with players of varying ages and skill sets. At one basket, local seventh graders are working on their conditioning. At another, middle-aged men can barely get their feet off the ground. On the other side of the gym, former New York Knick Charles Smith is playing with a group of teenagers.

Pyonin looks around his domain and smiles for a moment. Maybe one of these kids will become the next Edgar Jones, the next Randy Foye, the next Kyrie Irving.

After all these years, the passionate coach still has fire in his belly. "I know the grass is greener in other places but I don't care," Pyonin says. "I want my guys to play like somebody is taking food off their table. That's how they make it."