Three-point shooting proving to be a decisive factor in NBA Finals

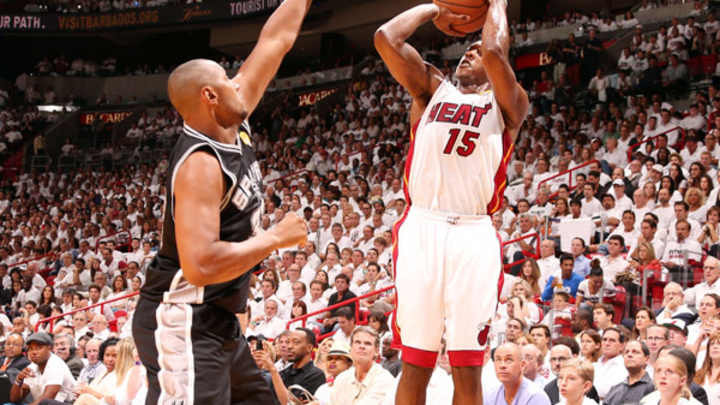

Mario Chalmers hit 2-of-4 three-pointers in Game 2, leading all scorers with 19 points. (Nathaniel S. Butler/NBAE via Getty Images)

These NBA Finals have been packaged as a duel of star trios, but even more fundamentally, they're a battle between two teams who best understand the value of the three-point line. San Antonio and Miami have both engineered their offenses around the space and efficiency that comes through long-range shooting, and execute every play with the intention of exploiting that advantage. Even as the leaders and shot creators of both teams stand front and center, they do so on the shoulders of their sharpshooting teammates. LeBron James would be great in most any basketball context, but he's only only capable of reaching such staggering heights by way of the stretched-out driving lanes and kick-out options afforded by perimeter marksmanship.

With that in mind, the usage and defense of the three-point line isn't merely a subplot of this championship series, but a decisive factor. For the Spurs and Heat, the three is a preferred option rather than a last resort. It's the primary counter to the sophistication of their opponent's defense, and an essential component in contending at this lofty a level. For those reasons alone it warrants examination and consideration beyond a casual glance at both teams' raw shooting numbers. Let's endeavor to do just that by focusing on a few prevalent three-point-centric themes of the first two Finals games.

• The right looks in the wrong places. Location, rhythm, timing, coverage and confidence all come into play during a three-point attempt, to say nothing of the more general quality of the shooter. Yet all of those interrelated factors can be so easily forgotten when a player misses an open shot or converts a more difficult one, in largely the same way that result tends to overwhelm process in most every fashion of basketball analysis.

But let's consider the performance of one particular long-range shooter (Miami's Mario Chalmers) as it relates to one particular variable (location). Chalmers in no way lacks for boldness, and tends to hoist up shots from any spot along the arc so long as there's an open window. Yet he's a decidedly better shooter from some spots than others -- a tilt in his game that becomes especially apparent if we split the court up into the left, right, and center sections. The shot chart below -- courtesy of Vorped -- is divided on those lines, and filtered to only include Chalmers' field goal percentage on jump shots in the regular season*:

*While this chart doesn't include his attempts from the postseason, his postseason shooting is marked by a similar trend.

A similar split isn't uncommon among right-handed shooters, many of whom fare best from the right side of the floor. Yet Chalmers' performance seems especially segmented, particularly when it comes to his accuracy in the corners; although he converted an outstanding 55.6 percent of his threes from the right corner, Chalmers made nearly 20 percent fewer (36.7 percent) of his threes from the left. There seems to be no deeper explanation for that divide save to say that every shooter has his on-court comfort zones, and that Chalmers must find the right wing and corner to be more cozy.

Nevertheless, this is the kind of situational split of which the Heat must be mindful, and which illustrates some of the improvement in their shooting between Game 1and Game 2. Chalmers had some good opportunities from beyond the arc in the opening game of the series, including this wide-open look courtesy of LeBron James' work in the low post:

Let's circle back to Chalmers' attempt for a moment:

San Antonio would have to go out of its way to give Chalmers a bigger opening, and yet he was ultimately unable to connect on this particular shot. It's still an attempt that Miami will take on most any given possession, though the Heat did themselves one better by again working James on the left block while allowing Chalmers to set up shop in the opposite corner:

This is only possible because Miami subbed out Udonis Haslem for Mike Miller. With Miller able to spot-up at the top of the floor without cluttering James' post-up, Chalmers was free to linger in the right corner and give James an even better outlet option than before. Chalmers' corner attempt was no less open than his prior shot from the left wing (largely because James drew the attention of four Spurs defenders), but both the process and outcome are different because the ball finds Chalmers under more favorable conditions. It's not a coincidence that three of Chalmers' four long-range makes in this series have come from that right corner, or that so many of Miami's play designs run him to that side of the court. The improvisational nature of basketball sometimes lands Chalmers on the left wing, but Erik Spoelstra and his staff are undoubtedly aware of the fact that Chalmers' shooting game leans to the right, and will steer him that way as much as possible.

One relatively simple way to do so is to run James to the post more often, using Chalmers as the post entry passer (where he would feed James and then cut baseline to the right corner). James' work in the post comes almost entirely from the left wing and block, and thus pairs perfectly with Chalmers' shooting from the opposite side of the floor. Plus, with the way Chalmers and James were killing the Spurs with the pick-and-roll in Game 2, it makes all the more sense to start Chalmers with control of the ball on the left wing with James, and then transition into either feeding James in the post or pulling him into a high screen. That's a dangerous playmaking combination, as both the high pick-and-roll and the James post-up yield ample opportunity to kick the ball to open shooters in the corners (maybe Chalmers, in the case of the post-up plays, or Ray Allen or Mike Miller otherwise).

• The pick-and-roll vehicle. The two-man game is both essential to NBA offenses and tagged with an incredibly misleading name. By its very label, it would seem as if there are only two options created on such plays: for a ball handler to weave his way to the rim or an open jumper, or for a screener (and subsequent roller) to do the same. Yet the best offensive teams use that basic premise as a means to create more interesting play action, with the Spurs perhaps leading the league in that particular brand of expanded utility.

The key to offensive execution lies in instigating defensive compromise -- an outcome best achieved by forcing opponents to make as many decisions as possible. The two-man game is merely a simple means to begin that process. Every screen used in an NBA game creates a physical buffer between the offensive player and recovering defender, but the far greater advantage comes in the corresponding deliberation. The implicit goal isn't merely to wipe out an opponent with a hard screen and free up a lane to the rim, but to turn every defender into Hamlet -- so paralyzed in navigating every decision that a shot is up and in by the time they discern the optimal course. With San Antonio specifically, it's trying to decide how to defend Tony Parker and Tim Duncan as a screen-and-roll pair, a challenge made even harder while attending to the Spurs' variety of three-point options. Trap Parker, and Duncan springs open. Rotate to Duncan, and risk leaving Danny Green or Kawhi Leonard on the perimeter. The hurdles in judgment are constant, and all keyed by one of the simplest actions in basketball.

Yet San Antonio is so well-schooled in every possible outcome of its pick-and-roll execution that in many cases even the initial screen is a ruse. Parker might drive around Duncan's pick simply for the purpose of forcing the defense to respond, all while intending to reverse the ball to Duncan to set up a shooter on the weak side:

Or Manu Ginobili -- San Antonio's go-to playmaker with Parker off the court -- might simply feed Duncan knowing that the defense will inevitably swarm his position in the lane:

San Antonio is such a fantastic offensive team because its philosophy revolves around means rather than ends, options as opposed to a single endpoint. They focus on running an offense that could well use the pick-and-roll as a play in itself or could build off of that initial drive with a series of redirections and swing passes.

None of that has changed after Miami's dominant Game 2 victory, and if anything one could argue that Parker and Ginobili were a bit impatient in trying to finish every possession with a single play on Sunday night. They got cute with passes that could have been more basic, and too often overlooked the possibility of flipping the ball to Duncan and extending the play with the extra pass. For that reason, over a quarter of the Game 2 plays that ball handlers used out of the pick-and-roll ended in turnovers, according to Synergy Sports Technology, offsetting the fact that San Antonio converted 46.7 percent of its spot-up three-pointers for the evening. The Heat's pressure-heavy defense has a lot to do with the Spurs not always getting the ball where it needs to go, but the basic playmaking structure to beat those traps remains. Parker and Ginobili will have the outlets necessary to make the right plays, but -- along with Duncan, Diaw, and any other intermediary passers -- will need to read situations more effectively in Game 3 and beyond to stretch Miami's on-a-string defense to the point of breaking.

• The three-pointer as a tactical counter. As good a defensive team as the Spurs are, their lockdown efforts on James and the Heat come with constant risk of a game-turning explosion -- as evidenced by the 33-5 second-half run that turned a competitive Game 2 into an apocalyptic blowout. That's bound to happen; Miami's "extra gear," is very real and very dangerous, and tends to render even sterling defensive execution irrelevant.

Still, San Antonio will go about defending intelligently and effectively in much of this series, and thus far has been aided in that effort by two two strategic decisions -- both of which play into the perimeter-shooting theme. The first is an explicit plan for James' on-ball defender to go under any potential screens, thus affording him the chance to fire up a quick jumper but guarding against the possibility of a potential drive. This is a smart move by Gregg Popovich and his staff, even though it cedes open looks to a player who shot 41 percent from beyond the arc this season. There are gambles worth taking, and any that decreases the likelihood of a James drive and increases the chance of him taking a jumper is absolutely worthwhile.

That said, James knows that his shot is being challenged, and has thus far responded to that challenge in two different ways. In some spots, he's elected to attack the under outright by taking the bait:

These misses technically play right into San Antonio's hand, but when taken selectively they aren't bad shots, per se. If these shots fall, they could influence the coverage of the Spurs' perimeter defenders, and thus could offer James more to gain than a mere three points. Nevertheless, it's best that he take these kinds of shots sparingly, and he has over the first two games of this series.

James could look to attack his opponent directly by driving into the cushion between him and his under defender out of pick-and-roll situations, but the Heat settled into a far more prudent strategy of shifting James into more dynamic situations. He finally started posting up with regularity in the second half of Game 2, and I'd be shocked if Spoelstra and the Heat didn't go to that option more consistently going forward. Additionally, by using James as a screener for Chalmers, Miami was able to mimic its usual pick-and-roll execution by getting James the ball in the middle of an array of open shooters:

It's a bit more complicated to have to rely on Chalmers threading that initial pass to James so that he can then dish the ball out to open shooters, but Miami's offense should be in great shape so long as that initial feed can go off without a hitch.

That brings us to the second Spurs stratagem designed to target James and Dwyane Wade, specifically: The decision to orient nearly every Spur right around the edge of the paint as a means of creating multiple help scenarios and minimizing rotation time. San Antonio isn't quite packing the paint, but it walks the line by straying from perimeter shooters just enough to crash on the drives of James or Wade. This is a precarious balance to maintain, and one that James is already looking to exploit with some regularity. In some cases, it's as simple as him -- or Wade, in this case -- driving into the help knowing where the open man might be:

In others, James swings the ball early to take advantage of the Spurs' placement and inattention:

The former makes for a more conventional basketball play, but there's nothing wrong with the latter scenario provided that James can get his teammate the ball in position to either make a shot or subsequent pass. If done correctly, it could make for the kind of quick-hitting score that challenges the Spurs commitment to this particular strategy, or at the very least return some easy points from Miami's supporting cast.