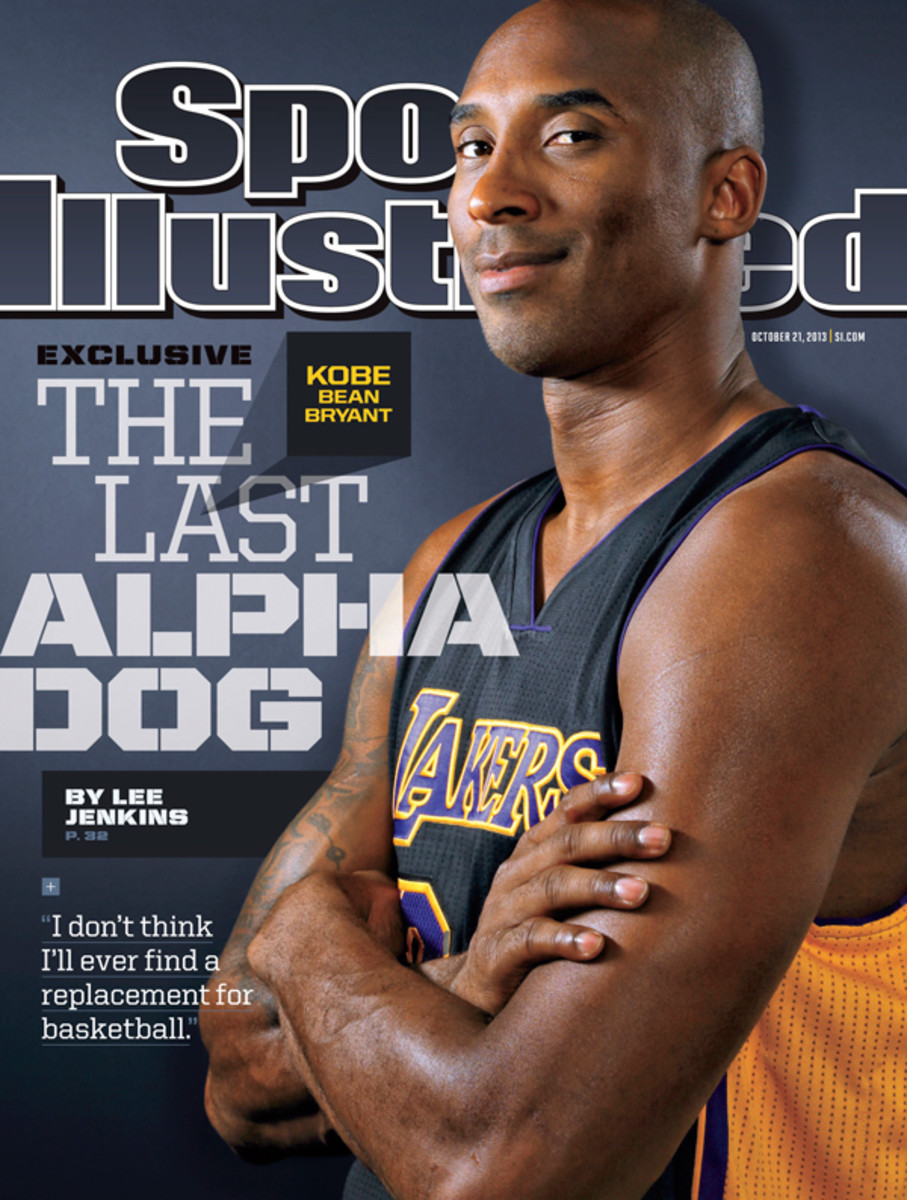

Lakers' Kobe Bryant appears on cover of Sports Illustrated's Oct. 21 issue

Kobe Bryant graces the cover of the Oct. 21 issue of Sports Illustrated. (Walter Iooss Jr./SI)

Lakers guard Kobe Bryant appears on the cover of this week's Sports Illustrated as he moves closer to returning from a devastating Achilles tendon injury.

Senior writer Lee Jenkins' story, which you can read here, builds out in many directions from a candid, extended one-on-one conversation with the 15-time All-Star and five-time champion, but the piece's lasting impact is less "interview" and more "anatomy of a competitor." That Bryant happens to be a legendary workaholic, and that he happens to be rehabilitating from a potentially career-altering injury, only ratchets up the stakes.

The reader is presented with a wounded, recovering, honest and fairly upbeat Bryant, who not only reflects on his current health but also offers insights into how his ruthless drive formed. The range is a bit startling: One minute, Bryant confesses that his career could be at a crossroads because of his Achilles injury, and the next he's pulling inspiration from a karate class he attended when he was 4 years old. From Jenkins' piece:

In an age when athletes aspire to be icons, yet share the burden of success with all their best pals, Bryant looms as perhaps the last alpha dog, half greyhound and half pit bull. No one handles him. No one censors him. He shows up alone. “What am I trying to be?” he asks. “Am I trying to be a hip cool guy? Am I trying to be a business mogul? Am I trying to be a basketball player?” He doesn’t provide an answer. He doesn’t have to. It’s been obvious since he was 6 years old in Italy and a club from Bologna tried to buy his rights. The gym was the place he could go at 4 a.m., “to smell the scent,” and pour the fuel. Bryant wonders whether his sanctuary is finally closing, and if so, how he will cope without it. He recognizes what many around him do not: the image, lifelike as it may be, is only partly real. Beneath it is a three-dimensional figure, with the same vulnerabilities as anybody else, plus the will to overcome them.

“I have self-doubt,” Bryant says. “I have insecurity. I have fear of failure. I have nights when I show up at the arena and I’m like, ‘My back hurts, my feet hurt, my knees hurt. I don’t have it. I just want to chill.’ We all have self-doubt. You don’t deny it but you also don’t capitulate to it. You embrace it. You respond to it. You rise above it. ... I don’t know how I’m going to come back from this injury. I don’t know. Maybe I’ll be horses---.” He pauses, as if envisioning himself as an eighth man. “Then again, maybe I won’t, because no matter what, my belief is that I’m going to figure it out. Maybe not this year or even next year but I’m going to stay with it until I figure it out.” He sips his latte. Housewives flit around the courtyard in yoga pants. A girls’ basketball coach from Costa Mesa High School delivers a note asking him to speak in front of her team. The coach writes that the girls need inspiration. This must be what she has in mind. Bryant slips the note into the pocket of his black windbreaker.

...

Winter of 1983 and 4-year-old Kobe Bryant signs up for karate classes at a dojo in Houston. His father, Joe “Jellybean” Bryant, is playing his final NBA season for the

Rockets

. Kobe is on the fast track to yellow belt. “One day, the master of the dojo came to me and said he wanted to put me up against a brown belt,” Bryant says. “I started crying. I told the master, ‘That kid is so much bigger than me. He’s so much better than I am.’ The master said, ‘You fight him!’ So I stepped onto the mat, with my headgear on, my shiny red gloves. Kids were sitting all around the perimeter. I was so freaked out. I got my ass kicked, but I did get a couple good licks in myself, and I remember sitting there at the end thinking: ‘It wasn’t as bad as I feared it would be. It wasn’t as bad as I imagined.’ I think I realized then that your mind can wander and come up with the worst, if you let it.”

The karate vignette is one of many that Jenkins traces chronologically, as the reader learns that Bryant didn't score a single point during a 1991 summer league, that he took the court with no mask despite a broken nose to win a crucial high school game, and that he opened up to Lakers teammates during a players-only meeting in 2001. As the stories tick off, the portrait of the strong-willed, stubborn Bryant comes together in full. The "take no prisoners" details are intense: Bryant stopped to think in 2004 that his legacy hinged on whether he could win a title without Shaquille O'Neal; Bryant once invited O.J. Mayo to a 3 a.m. workout when the high school phenom assumed it was set for 3 p.m.; Bryant plans to rely on his fundamentals like boxer Floyd Mayweather once he's back on the court; Bryant showed his 7-year-old daughter a tape of his 2008 Finals loss to comfort her after a disappointing soccer game.

SI.com's 2013-14 NBA preview hub

But that's only half of this picture. The other half is the Bryant who spent months this summer without shooting a ball, the Bryant who has had some extra time with his family, but also the opportunity to think back on the Lakers' turbulent 2012-13 season. Although Bryant's time on the court ended after he tore his Achilles decided to take (and make) his two free throws and then hobbled to the locker room, his season also included a memorable encore. As the Spurs were putting the finishing touches on a first-round sweep of the Bryant-less Lakers, Dwight Howard was ejected from Game 4. Shortly after the All-Star center retreated to the locker room, Bryant emerged from the very same locker room and sat with his Lakers teammates. Predictably, he received a standing ovation from the Staples Center crowd.

http://youtu.be/MmkUWr4ih2E

Bryant gives Jenkins his version of the emotional moment, which has taken on serious symbolic significance now that Howard signed with the Rockets as a free agent while the Lakers' hopes are fully invested in Bryant:

Two weeks and two days later, the Lakers host the Spurs in Game 4 of the first round of the playoffs, and Bryant changes outfits in the locker room. He needs five minutes to pull his left pant-leg over the cumbersome boot on his left foot. As he limps out, center

Dwight Howard

cruises in. “What the f--- is going on?” Bryant asks a trainer. “Dwight got ejected,” he is informed. In the retelling, Bryant waits eight seconds to utter another word, as if literally biting his tongue. “Sports have a funny way of doing s--- like that,” he says.

The Lakers are about to be swept and Howard is about to leave for Houston, where he will forfeit $30 million and avoid discomfort. But Bryant is the rare modern athlete whose presence can transcend playoff results and free-agent decisions. Sometimes, just seeing him is enough. “The long year, the injuries, the Shaq stuff, the Phil stuff, it all came to a head when I walked out to the bench,” Bryant says. “It was the first time I ever felt that kind of love from a crowd. Oh my God I was fighting back the tears.”

GALLERY: Rare photos of Kobe Bryant

It's abundantly clear throughout -- in Jenkins' depiction, as well as Bryant's -- that Bryant believes the emotional scene marked the end of a season and a partnership, but not a career:

He adopted a title for the next phase of his career, which will begin when rehab ends and he sticks that gold Lakers jersey back in his teeth, whether on opening night or Christmas Day or sometime in between. “It’s The Last Chapter,” Bryant says. “The book is going to close. I just haven’t determined how many pages are left.”

In case you were wondering, Bryant appears on the cover wearing the Lakers' new black "Hollywood Nights" alternate jersey.

Sports Illustrated