Unlocking Al Jefferson: The secret to the big man's recent dominance in the paint

Al Jefferson has been outstanding of late, in part because he's been given room. (Andrew D. Bernstein/NBAE/Getty Images)

In a league full of aesthetic and athletic wonders, Al Jefferson stands apart. He's a lumbering big man out of sync with the evolution of the league, and at the same time stands in sacrilege to all the hallowed tenets of post play. His pump fake is patently outrageous. His hook shot scoffs at fundamental form. He's not of a different time, but of a different dimension entirely.

As such, even Jefferson's brighter moments don't resonate at quite the same frequency as the NBA's other stars -- a fact evidenced by the air of quiet surrounding his recent tear. Over his last 12 games, Jefferson has averaged a staggering 27.4 points (on 54.8 percent shooting), 12.1 rebounds, and 2.7 assists without much ado. That the Bobcats are squared away on the NBA's margins is to blame for some of that inattention, but one can't ignore Jefferson's style as a factor in his inability to capture the basketball world's interest. While Kevin Durant is throwing fireballs, Al Jefferson is rolling bocce; his very style brings the game to a deliberate walk, replacing dynamic drives and sharp shooting with the slow churn of his idiosyncratic post work.

That divide doesn't preclude Jefferson from being effective in his own right, particularly when given room to operate. Actually carving out such room, though, has been a recurring problem for the Bobcats all season. Charlotte runs all kinds of precursor action -- screens, decoys, redirection -- to get both Jefferson and his teammates in proper position for a post-up. But that preamble only goes so far; no matter its clever designs, Steve Clifford's playbook has all too frequently bumped up against the limitations of his roster.

GOLLIVER: All-Dunk Contest Team: Dream six-man field to save All-Star's showcase

The most persistent constraint therein comes through the Bobcats' lack of competent perimeter shooters. Kemba Walker has inched toward league-average accuracy from beyond the arc, an improvement which depressingly makes him one of Charlotte's better marksmen. Gerald Henderson (29.3 percent), Michael Kidd-Gilchrist (11.1), and Ramon Sessions (11.9) are utter irrelevants from behind the three-point line. Jeff Taylor, who showed some promise as a spot-up type as a rookie last year, shot poorly prior to his season-ending surgery. Even those deep reserves (Jannero Pargo, Ben Gordon) who might help space the floor are so lacking in other regards that it's difficult to play them. In all, only two teams in the league average fewer three-point attempts per game than the Bobcats, a weakness which ultimately draws bigger problems inward.

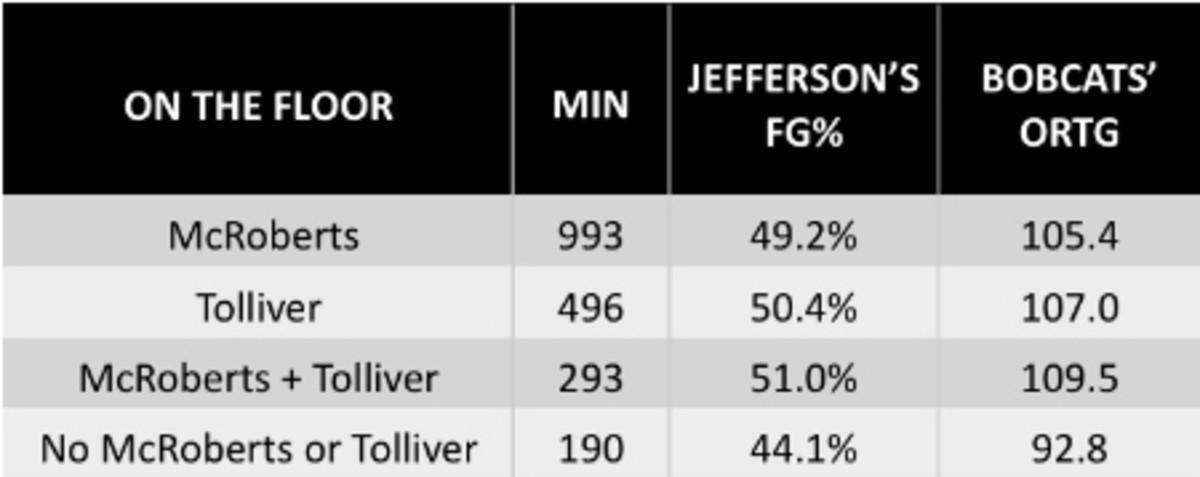

Yet Jefferson has found his way as a Bobcat all the same, in part due to a progressive effort to pair him with the best shooters available. Walker has been in and out of that mix due to injury, but Charlotte has improbably relied on Josh McRoberts (a power forward who shoots 37.5 percent from deep) and Anthony Tolliver (a one-time benchwarmer making 44.4 percent of his three-pointers) to facilitate their post play. Neither is anything more than a role player, and Tolliver, in particular, has only found his way into the regular rotation due to injuries to Taylor and Kidd-Gilchrist. But the very presence of those two rangy forwards has opened things up for Jefferson and the Bobcats offense, particularly when they complement Big Al in tandem:

Data provided by NBA Wowy.

Dicing up Jefferson's minutes based on teammate pairings creates a bit of a sample size issue, but the initial trends are both observable and prominent. McRoberts, who has started 49 of Charlotte's 50 games this season, is both a reasonably effective shooter and a practical entry passer -- two attributes that naturally play off of Jefferson's strengths down low. In that synergy one can find explicable reason for offensive success; McRoberts' particular skills and range allow him to operate in spaces of the floor that wouldn't crowd Jefferson's post work. Tolliver makes for less direct influence due to the fact that he's primarily used as a spot-up shooter on the weak side of the floor, but he's so much more effective than his Bobcats teammates in that regard that his presence on the floor makes a tangible impact.

There are, of course, other factors in play; Jefferson is not only fully healthy now after battling through early season injury, but has had an opportunity to work himself into a productive rhythm; Walker's absence forced Charlotte to funnel its offense through Jefferson even more, which drew more strategic focus to the team's floor spacing; and ultimately, it's taken time for a young team to take to some of the specifics of Clifford's newly installed offense. The first -- Jefferson's health and mobility -- in particular, should not be underestimated. But consider the alternative to the McRoberts/Tolliver remedy through the lineup of Jefferson, Sessions, Kidd-Gilchrist, Henderson, and Cody Zeller:

Hover over image for dynamic captions and video playback.

Not a single one of Jefferson's four teammates on the floor in this scenario can shoot from long range, meaning the only space that the Bobcats' opponent (in this case, the Clippers) has to defend is within the arc. That interior focus then brings a ton of attention to Jefferson and the paint; without need to stretch coverage out to the three-point line, it's only natural that the defense would primarily look to take away the highest-percentage shots available. As good as Jefferson is on the block, asking him to create in close quarters with all five defenders looming is a bit much, hence Charlotte's miserable offensive performance (and Jefferson's substandard field goal percentage) when he works without McRoberts or Tolliver.

MAHONEY: The Fundamentals: What's holding DeAndre Jordan back?

Put one of those two on the floor and Jefferson gets some helpful breathing room. Stick both into the lineup -- as is the case in Charlotte's most-played unit for the season -- and things get much more interesting for what has, on balance, been one of the worst offensive teams in the league (27th in points per possession). Tolliver's emergence has been noticeably advantageous in that regard, if only in accomplishing the former; Jefferson now only plays about a tenth of his minutes without one of his complements in tow, relative to a quarter of his minutes during the opening stretch of the season.