New book explores what makes Michael Jordan tick

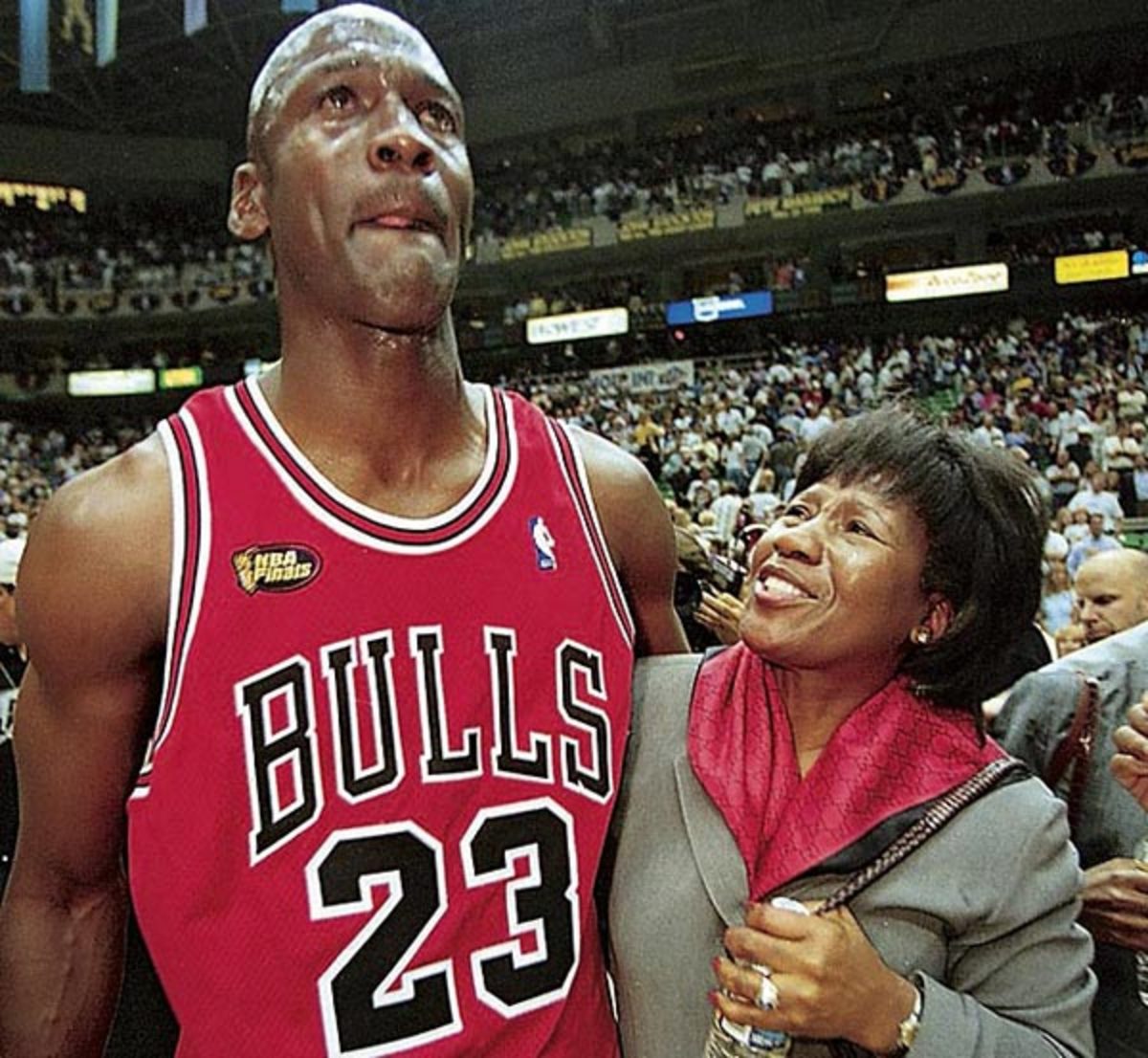

Michael Jordan with his mother, Deloris, after winning the 1998 NBA Finals. (Walter Iooss Jr./SI)

So much has been written about Michael Jordan that sometimes it's hard to think there's more we don't know about him. Roland Lazenby set out to fill in those gaps in his new book, Michael Jordan: The Life, which will be released on Tuesday.

Lazenby spends a good portion of the book writing about Jordan's family history, as well as the unmatched competitive drive that informed everything the six-time NBA champion has done on and off the court. Jordan "remembers everyone who ever didn’t think he was going to be great," former Bulls general manager Jerry Krause says in the book. "He remembers every negative story that’s ever been written about him.”

Lazenby -- who has also written books about Phil Jackson and Jerry West -- attempts to go "full circle," bringing Jordan from awkward youth in Wilmington, N.C., to mythic superstar to struggling NBA owner. SI.com spoke with Lazenby about the book and the things that helped make Jordan into "23."

SI.com: When you looked into his family’s past and the events that shaped North Carolina, what were you surprised to learn?

Roland Lazenby: I’ve lived all of my life in Virginia. I’ve been to North Carolina hundreds of times and enjoy it tremendously, but North Carolina was a state that had more Klan members than the rest of the Southern states combined. As I started looking at newspapers back in this era when I was putting together Dawson Jordan’s [Michael’s great-grandfather] life, the Klan was like a chamber of commerce. It bought the uniforms for ball teams, it put Bibles in all the schools. It may well have ended up being a chamber of commerce if not for all the violence it was perpetrating, too. A lot of the context just wasn’t possible to put it in a basketball book. A lot of it ended up being cut.

I was really stunned at what a cultural influence the Wilmington Riot or insurrection [of 1898] and the whole birth of white supremacy had. It had me recalling an interview with John McLendon, the great coach at North Carolina Central and other places, in the early 1990s. He had said, “You know when I got to North Carolina Central as a young coach, I was really astounded at the beaten-down mental attitude. I had to convince my athletes that they weren’t inferior.” That was one of those interviews that just resonated. I don’t think there’s anything that encapsulated the twisted mindset of our racial history more than that.

GALLERY: SI's 100 best Jordan photos| Jordan in college | Jordan playing baseball

When Jordan comes into the NBA, very soon there are expectations of him to be this citizen, this spokesperson who can stand up and could’ve supported [former North Carolina Senate candidate] Harvey Gantt and done those things, but that wasn’t the cultural story of blacks on the Coastal Plain. They had no political power. None of Jordan’s people were ever registered to vote. Every gain that African-Americans made was economically based. This system of sharecropping was so rigged. I thought it was fascinating that Jordan’s mother’s father [Edward Peoples], out of all those people who were destroyed financially with sharecropping, here’s this guy who succeeded and came to own his own land. He was just driven economically. Jordan’s mother, as you go through the book, is sort of the firebrand who delivers things when Mike’s too young or immature to really recognize opportunity or seize on it.

As I researched, the whole thing began to take form in my mind that we really don’t think of Michael Jordan that way. He’s been lampooned a lot because he was so great as a player that no matter what he did people were going to be disappointed in him. People look back on him playing baseball and now they think what he did there was remarkable. At the time, man, people were all over him. A lot of what he did with the Wizards obviously wasn’t mistake-free. But when you stop and look at it in the rear-view mirror a bit, you have to give him his due. I started looking at Charlotte. He was rescuing the Chernobyl of the NBA after what happened with the Hornets the first time around and the poorly planned rollout of the Bobcats. It’s an economic story. It’s a black power story. It doesn’t come from politics or protests, it comes right off the Coastal Plain of North Carolina and out of the African-American experience.

Some of that sounds like the language of a reach, but I don’t believe it’s a reach. I think it’s exactly what it is. That drive and that influence of his mother was such a big factor. That’s all I heard everywhere I turned.

Michael Jordan spent 13 seasons with the Bulls and two with the Wizards. (Simon Bruty/SI)

SI: One of the narratives you tend to weave in and out throughout is Jordan's competitive streak -- all of these things he pulled from, real or imagined. What inspired that streak for him and just how important was it to making him an icon?

RL: It’s a father-son story in a different sort of way. I was a night police reporter at the Roanoke Times in 1980-81 when my father was dying of brain cancer. I had played a year of college football and three years of rugby, but he had always been a basketball nut. He even played some semi-pro ball. My father dies under fairly difficult circumstances. I begin playing pickup basketball like crazy and I spend my life writing basketball books.

In a totally different way, Jordan and so many other people spend their lives recognizing or having this debate or response to their parents. It’s revelatory to me personally. It’s not that we don’t know about these themes. Sometimes seeing them right there in the life of someone like Michael Jordan, we suddenly begin to understand ourselves from that. The thing that blew me away was the setup to that, as I learned of Michael’s failure in youth league baseball. I had no idea that his baseball career, which was so important to his father, collapsed on him.

SI VAULT: Was Jordan really cut from his high school team?

You think of Jordan as this superhero. Here he is as this obviously great Little League player, and he did make the All-Star team in high school, but he never really made it in three years of Babe Ruth League ball. I just found that to be unfathomable. He really made great use of that stuff [for motivation]. Later, reporters began to discover he wasn’t above making up things, too. He was very much in tune with his mental devices. I was really fortunate to have [sports psychologist] George Mumford explain those things to me. That’s a critical part of understanding not just that he was so competitive but also how he was so successful. This ability to get to that level of focus.

SI: Regarding that us-vs.-them, me-vs.-the world mentality, you mention in the book that’s something Phil Jackson was able to do so well. Because Michael had already created that for himself before joining the Bulls, was that perhaps why Phil was able to get through to him?

RL: I do. Phil can read people. He read Michael well. He had a chance as an assistant coach [with the Bulls before becoming head coach] to observe and to realize that this was an extraordinary force of nature, this competitor, and you have to make that work for you. Phil also witnessed plenty of times where it was destroying any effort at creating a team.

There were so many things working in Michael’s favor. I don’t think people realize that [longtime North Carolina assistant] Bill Guthridge played at Kansas State for [longtime Jackson assistant] Tex Winter as a lead guard and then was his assistant coach. He then went to North Carolina and really ran the show for Dean Smith as an assistant. Smith’s system wasn’t the triangle offense, but system basketball is really what it’s about. Tex was adamant to me that Michael could never have accepted the triangle as a pro player if he wasn’t able to accept that system basketball at North Carolina.

Michael Jordan (center) with coach Dean Smith and teammate Sam Perkins at North Carolina. (Lane Stewart/SI)

SI: You call Jordan's post-basketball career and tenure as an NBA owner his "second act." How do you think that has affected or altered the public’s (and by and large the media’s) perception of him?

RL: That us-vs.-them thing worked for him as a competitor, but it really made for nasty internal relations in Washington. Michael came into conflict with [late Wizards owner] Abe Pollin. That really just blew up to a point where a guy like Abe Pollin, who had never fired anyone, it was just savage what happened with Michael. Look at what Michael actually accomplished -- and set aside [drafting] Kwame Brown for a moment -- bringing in that massive amount of money to the team. Michael knew he had no hope of winning when he came back to play [for Washington in 2001]. Michael was trying to please Pollin and make the Wizards successful. It was a very sad moment for the NBA, a sad moment for Michael and a sad moment for Pollin near the end of his life. It ultimately probably helped Michael shake loose all the adoration. That stuff can bend your perspective like crazy. Washington was important for him. He obviously took a beating there, and he headed into another one of those situations in Charlotte.

This gets to the other big thing that Charlotte does. I sat down with [NFL player] Pacman Jones for this: In 2007, Michael was at All-Star Weekend in Las Vegas shooting craps. Pacman won $1 million, not $100,000 as previously reported, and he went off and got involved in an incident at a strip club. Michael, on the other hand, lost $5 million shooting craps. This is right at the heart of the time he was trying to become the Bobcats' primary owner. And he needs David Stern.

What does this tell you about the biggest issue for many people? It tells me that Michael was never suspended from the NBA for gambling. A lot of people like to play that myth [that an NBA suspension led him to turn to professional baseball in 1994] -- it makes for a great media play -- but I will tell you no one at any time, not even for a nanosecond, has suggested that Michael bet on basketball or on his own team or against his own team. There is no evidence that anyone ever suspended him. He certainly hasn't acted like it. The NBA has been a league of gamblers forever. In a lot of ways, the face of the NBA today is Charles Barkley, and he is a known and unrepentant gambler, as is Michael.

Stern didn’t just approve of Michael's being the owner in Charlotte; Stern went way out of his way to make that happen. It was important to him. If Michael had been so low as to do something to get suspended, there’s no way Stern would have ever done that for him in the future.

SI: You mentioned on Twitter you weren’t surprised by Jordan's initial comments about Donald Sterling. Why is that, and what is Michael’s role now that he’s an owner?

RL: Behind the spotlight, Michael lives this very open life racially. He’s the kind of guy who can say to a broadcaster in a pickup game, "You’re not black enough.” That’s sort of the sports ethos. It’s something we joke about until it’s dead serious. For Michael, it’s part of the territory. He’s the first former player to own a team. Timing’s everything. I wrote a series on race back in 1984. At that time, blacks could be excluded from juries just for being black. I was interviewing a black official who said, “All you have to have is one person in the room. They won’t drag out that good ole’ boy stuff and start playing those games if you have just one representative there.”