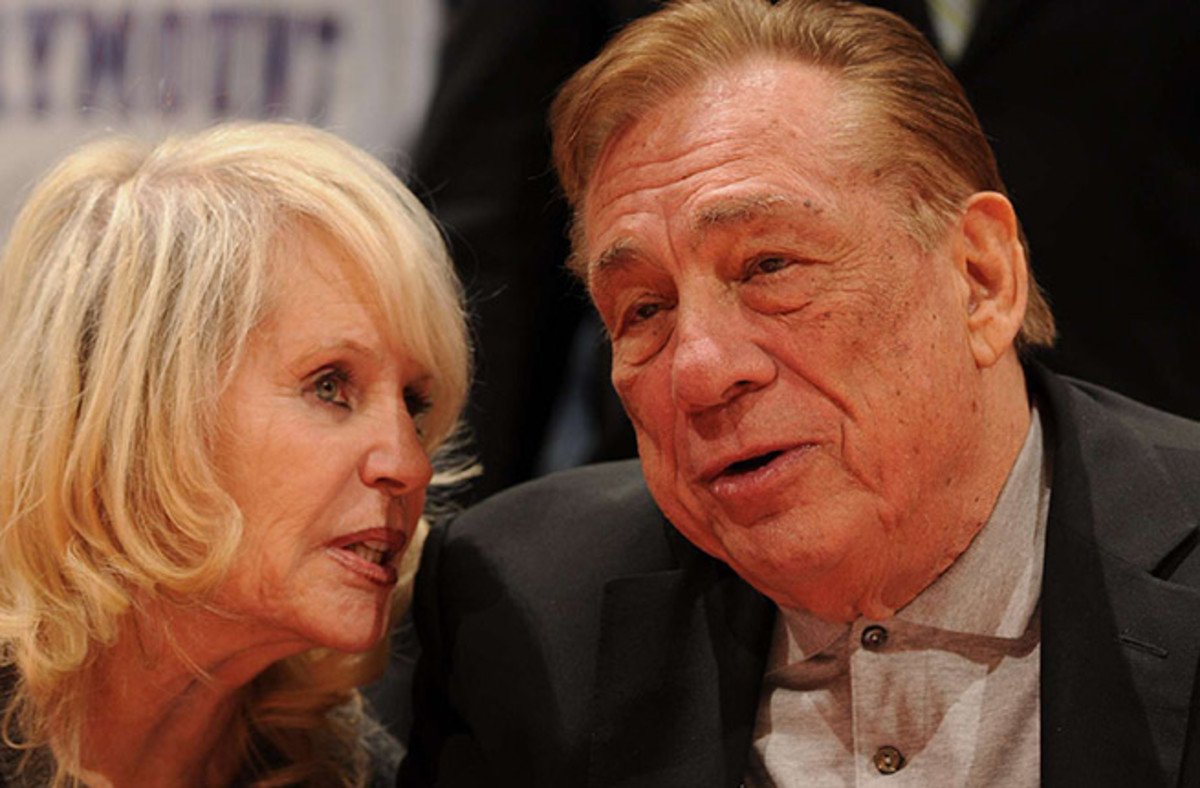

Recently banned Donald Sterling has long history of clashing with NBA

Simmons mostly kept watch over the franchise's finances, questioning every dollar that went out. Her office was next to the accountant's, and the path between their two doors was well worn. People liked Simmons and she worked hard, but her role in the organization put her at odds with others. Says Dunlap: "She was Sterling's spy."

From the start of Sterling's reign, the franchise's modus operandi appeared to be: Why pay a bill you can just ignore? After about 16 months, the NBA claimed the club owed $225,000 to the league, its owners, and two pension plans; $300,000 was past due to current and former players; another $300,000 was owed to third parties, highlighted by various hotels bills that went unpaid. One hotel with a long-standing relationship with NBA teams refused to host the Clippers late in the 1981-82 season.

One winner of a promotional contest had to sue the team to get the $1,000 he was owed. In other cases, Sterling proposed new prizes after the fact. One of his favorite tactics was to offer season tickets for "as long as the team is in San Diego," a clause that called to mind Sterling's past as a divorce and personal injury attorney and also his poorly-veiled desire to move the team closer to his home in Beverly Hills.

During and after that first season, members of the league office repeatedly attempted to communicate their concerns with the way the franchise was operating. They sent Telex after Telex to the Sports Arena offices, some marked "urgent," in which they demanded a response from the team. The Telexes were tossed into an empty office. Says Lees: "There were all these things where, and I don't think this is exactly what the league called it, but where we were accused of conduct unbecoming an NBA franchise."

The Clippers finished 17-65 in Sterling's first season, due in no small part to decisions he made that prioritized saving money over fielding a competitive team. He reportedly vetoed a trade with the Denver Nuggets that would have sent Alex English to the Clippers for Freeman Williams. Two employees said that Sterling would sometimes question random people about whether he should sign a player or make a trade. Late in that first season, after injuries depleted the team's roster down to seven players, one below the league-mandated minimum, the Clippers didn't acquire a proven player. Rather, the team signed Rock Lee, a former backup forward at San Diego State who played pickup ball near Bill Walton's house.

At a luncheon in January 1982, Sterling admitted the team was tanking in the hopes of getting the No. 1 choice in the draft. He said the Clippers were "biting the bullet," and "I guarantee you that we will have the first or second or third pick," among other remarks. The press recorded his comments and (in a forerunner to the scandal that would emerge decades later) the NBA reviewed the recording. Commissioner Larry O'Brien fined Sterling $10,000 for "conduct prejudicial and detrimental to the NBA."

In June 1982, a month after Sterling's one-year anniversary as an NBA owner, the Los Angeles Coliseum Commission announced that it had reached an agreement with him to move the Clippers to Los Angeles. The league learned of Sterling's intentions as it did with so many of his shenanigans, via the media. If his earlier antics had triggered warning signals, trying to move his team without warning was a screaming siren.

It prompted a bevy of lawsuits filed by people and businesses in San Diego that would be affected by the move. There was even a complaint filed by the L.A. Coliseum Commision against Jerry Buss, the Lakers owner, after Buss told reporters that he'd likely contest the Clippers move. The L.A. Coliseum Commission sued Buss not for actually challenging the move but merely for saying he would. From the various legal battles emerged further details about Sterling's mismanagement of the Clippers and the repercussions. In a lawsuit filed by the NBA against the Coliseum Commission, the league stated that players had threatened to sit out games because of the Clippers indebtedness, and that the NBA Players Association threatened to boycott the All-Star game. Charles Grantham, the executive vice president of the player's association in 1982, confirmed that the NBAPA threatened a boycott if the league didn't do something about Sterling's failure to pay players.

In September 1982, while under investigation by the league and facing multiple lawsuits, Sterling withdrew his application to move the team. But the die appeared cast on his fate. Later that month, a committee of six owners voted unanimously to recommend that he be removed. One unnamed owner told the San Diego Union: "That fact that Sterling wants to move the club is a separate issue. We've been concerned about him and what he's done to this franchise for months. And I'm not just speaking for a handful of owners -- I'm talking about 20 of us. There is overwhelming sentiment against Donald Sterling."

A meeting of the league's owners was set for Oct. 13 at the Hotel Del Coronado just across San Diego Bay. In the run-up to that meeting, more owners and NBA executives were quoted anonymously saying that Sterling's fate was sealed. One told the Los Angeles Times: "He's as good as gone."

Then, just days before the meeting, Sterling announced he was selling the franchise. "I'm not sure I was ready to own a pro team," he said. "Maybe I can make up for it by selling to someone who could accomplish what I couldn't." It was a cunning move, as the league postponed the vote on his removal.

David Stern, then the NBA vice president and the future commissioner, advised Sterling to hire attorney Alan Rothenberg to "straighten things up" (Rothenberg's words). Rothenberg, who later become one of the most important figures in U.S. Soccer as director of the 1994 World Cup and president of the U.S. Soccer Federation, initiated the hiring of a new general manager and coach and appeared, at least from the outside, to bring some much-needed order to the franchise. "Then we went to the league and persuaded them not go forward [with removing Sterling]," Rothenberg told SI.

In February 1983, five months after Sterling was "as good as gone," former Clippers general manager Ted Podelski filed a lawsuit against the team. (Podelski had been fired the previous October, learning of his dismissal just before the press conference announcing his successor.) The lawsuit did not dampen the league's newfound contentment over how the franchise was being run. Said Stern: "We are satisfied the team is being operated in a first class, professional way."

*****

Were the Clippers suddenly a model organization? Did Sterling, with Rothenberg's help, suddenly transform from Jackie Moon into Jack Kent Cooke?

It seems more likely that Stern -- who could not be reached for comment -- was worried about the fallout from attempting to remove Sterling, as the owner wouldn't have shied away from a contentious legal battle. The push to remove Sterling also came just three months after Al Davis, the Oakland Raiders owner, won his landmark anti-trust lawsuit against the NFL, allowing him to relocate the Raiders to Los Angeles. Perhaps a smart man like Stern (also an attorney) saw how Davis had become a perpetual and costly headache for NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle and thought it unwise to turn Sterling into a similar adversary. (Years later, Davis and Sterling would, coincidentally, become friends.)

Rothenberg says they were unable to find any "credible" buyers for the franchise, and Grantham, the former NBAPA executive, doesn't doubt that. "At that time, the owners and the players were all in the gutter together," Grantham says. "There were not a lot of people out there looking to buy an NBA team." He offers one addendum for why the league might have backed off Sterling. "If they forced him to sell, and the team went for less than what Sterling paid, that would have hurt all the owners."

Another possibility is that Sterling -- who has proudly described himself as a buy-and-hold investor -- never truly intended to sell. Al Davis' legal victory over the NFL opened the door for Sterling to move the Clippers north, and by 1982 the league and players' association had begun discussions about revenue sharing. Would Sterling, a man who made most of his fortune collecting rent, really have sold his team just before it landed in a better zip code and just before his fellow owners were to begin cutting him checks?

Despite Rothenberg's sprucing, the 1983-84 team, the last to play in San Diego, had Sterling's fingerprints all over it. The San Diego Tribune acquired a copy of the franchise's proposed budget for the year, and it showed that Sterling had cut expenditures to the bone. The allocation for scouting was to be reduced from $23,000 the year before to $1,100; advertising fell from $205,000 to $5,000; administrative travel dropped from $33,000 to $100; the training camp budget, once at $53,000, shrunk to $120. Most alarming was the reduction in expected medical costs, from $10,454 to $100. Stern's "first class" organization budgeted no more than $100 on expected medical costs.

The team also continued to employ Simmons. Rothenberg had replaced the general manager and the coach, but Simmons remained on the job. She became manager of the Ritz Colony, a large apartment complex Sterling owns in Encinitas, north of San Diego. She and Sterling were named in a lawsuit brought by a tenant who said she developed asthma because of mold in her apartment, and in 2002 a jury awarded the tenant $50,000.

On a recent Monday afternoon, Simmons was found in the office of the Ritz Colony. She is 65 years old now, but still blond and well-kept. She wore a blue sweater over a blouse on 80-degree day and white Keds, but her face had the appearance of a younger woman. She declined to be interviewed, saying she had just gotten out of the hospital and needed to return. She pointed to a bandage wrap around her arm as proof. Told that SI was writing about the wild days when Sterling owned the Clippers in San Diego, Simmons smiled and walked toward a back room of the office. She promised to call an SI reporter later (she never did) and then added:

"Yes, those were wild days."