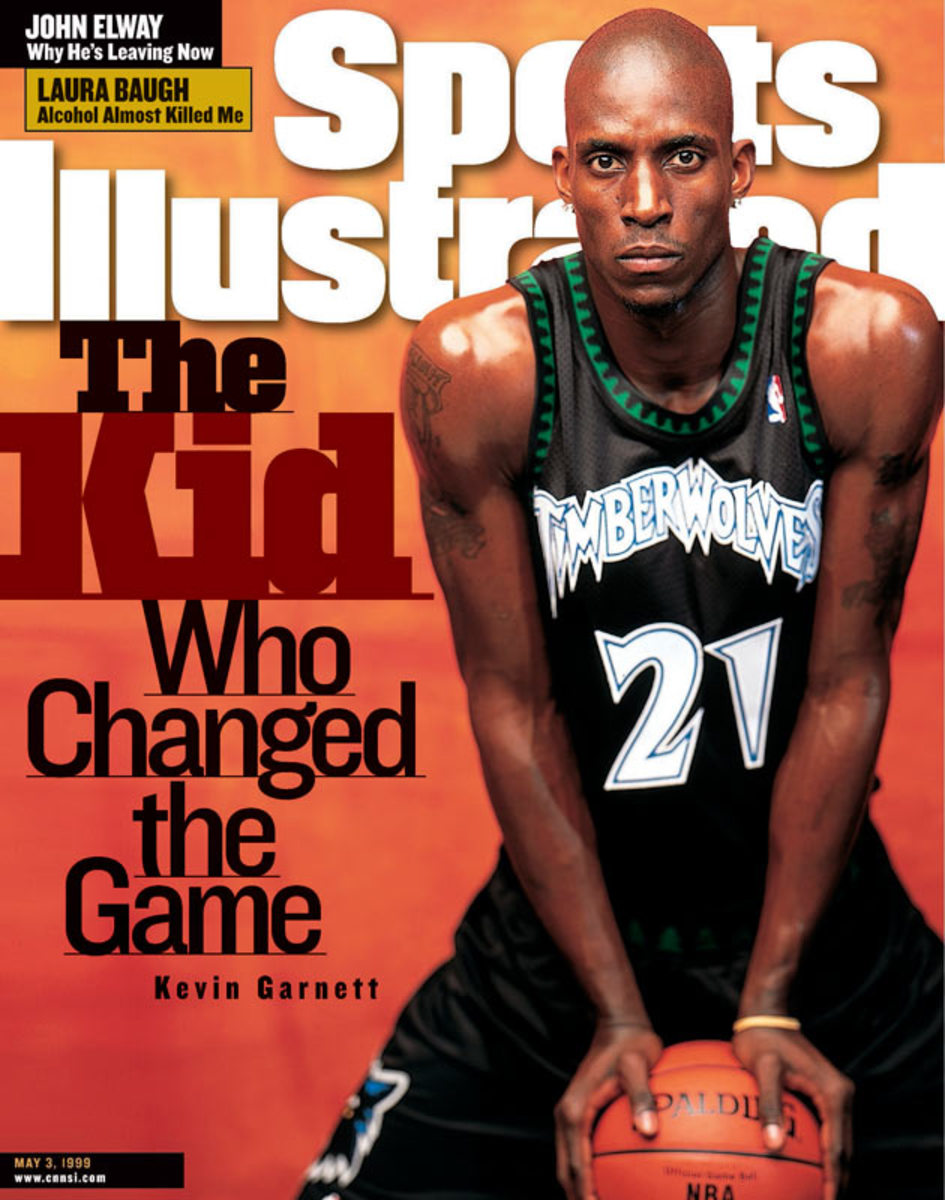

Kevin Garnett: The Kid who changed the game (and the Timberwolves)

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the May 3, 1999 edition of Sports Illustrated. The cover story was Kevin Garnett's first as a member of the Minnesota Timberwolves. In honor of his return to the Wolves this week, SI is re-running the feature, titled "Howlin' Wolf." To subscribe, click here.

A knock on a hotel room door at two o'clock in the morning in the first week of May 1995 was the beginning. Eric Fleisher, the sports agent, got out of bed, walked across the floor and looked through the peephole. Who could be here at two o'clock in the morning? Through the tiny opening Fleisher saw the largest kid he'd ever seen in his life.

"Kevin?" he asked.

"Yeah," the largest kid replied.

Fleisher opened the door....

Kevin Garnett entered.

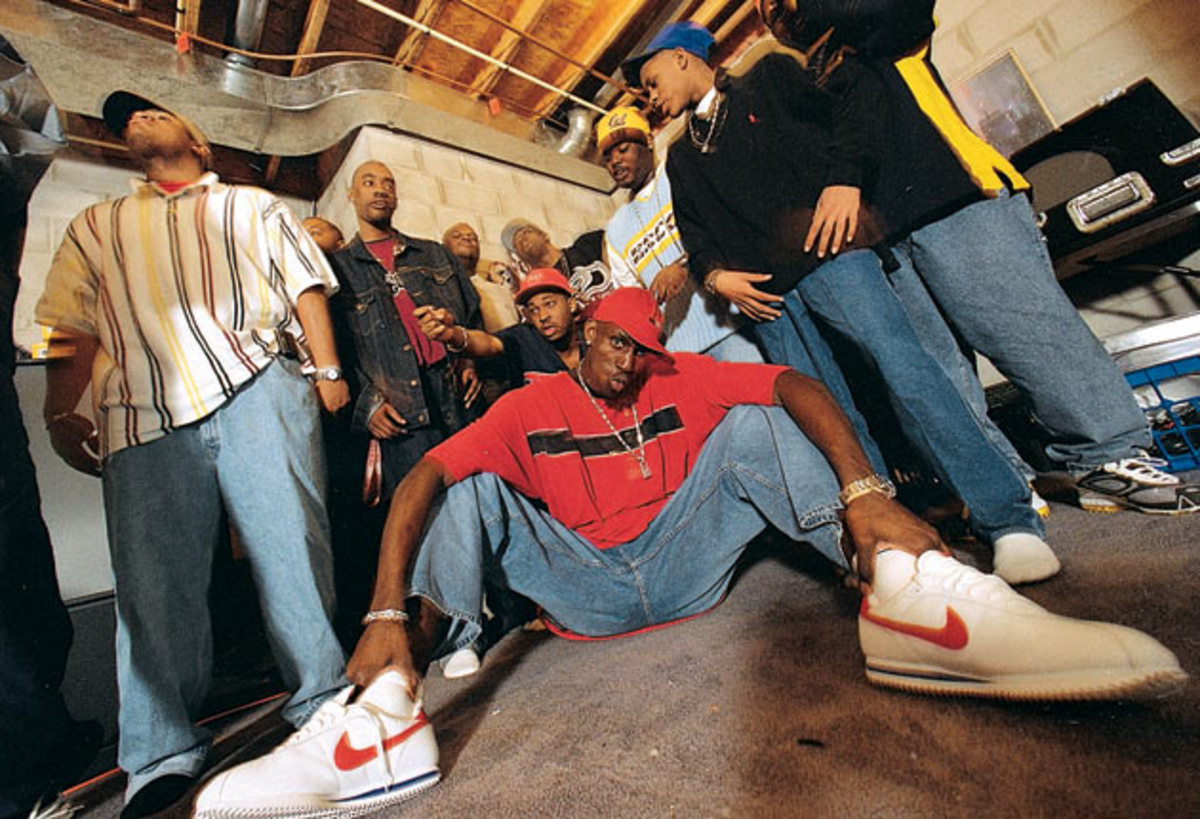

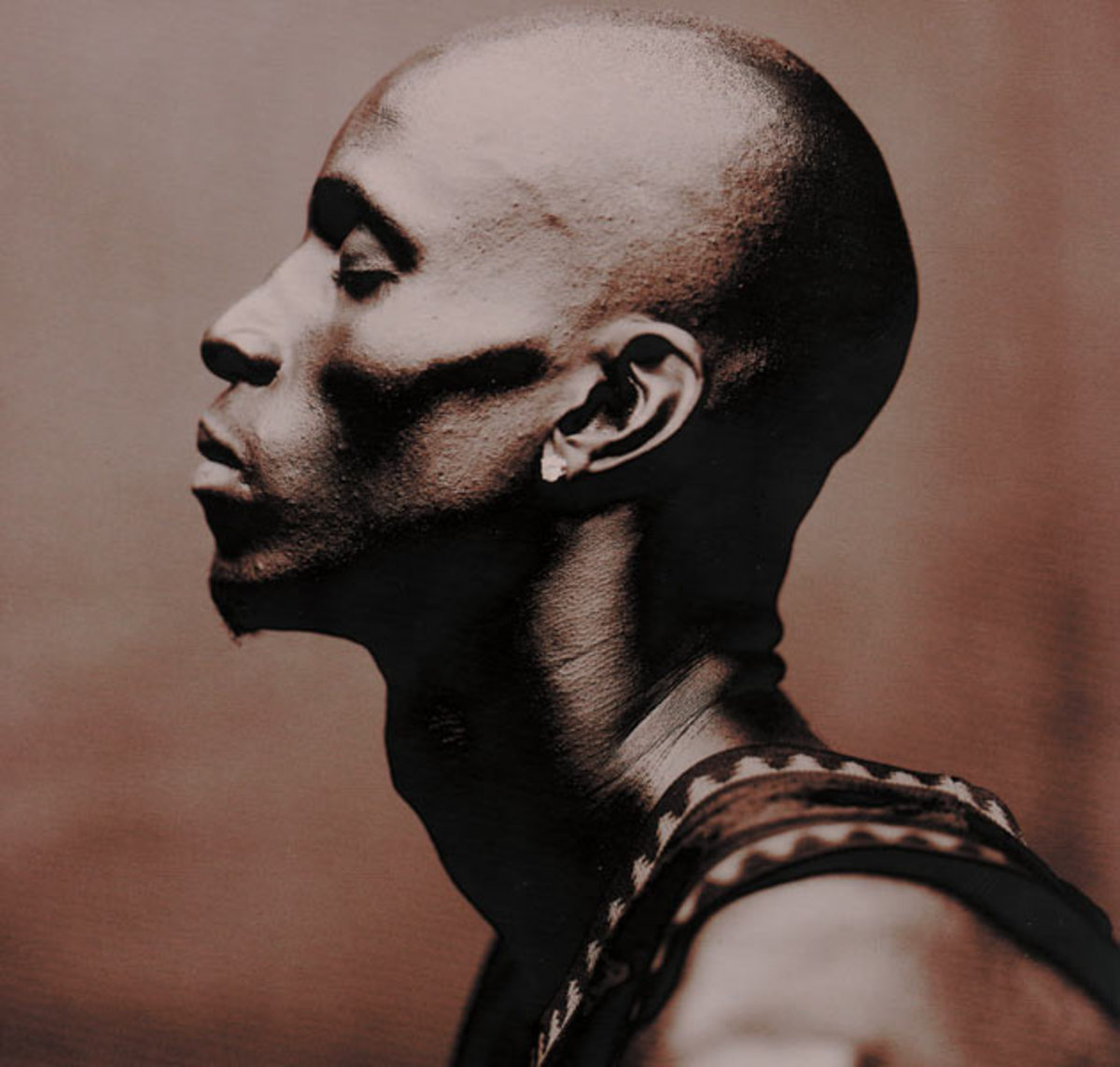

He was 6'11" and a spindly 220 pounds. He had a shaved head. He was accompanied by five other kids, friends from Farragut Academy on Chicago's West Side. They all were dressed in hip-hop style, big clothes hanging from their frames. They filled the hotel room.

Fleisher had been scheduled to meet with Garnett at seven o'clock the previous evening. The kid was seven hours late. It was not a mistake. He hadn't overslept or been delayed or simply forgotten where he was supposed to be. Tardiness was a strategy. The kid wanted to come in "hard." His word. He wanted the upper hand, the surprise, the control. He had figured all this out for himself. He was 18 years old.

"I didn't know this guy," Garnett says now. "He didn't know me. You hear so many things about agents, about people trying to take advantage of you. I'd had a lot of agents calling me, playing these childish games. I'd play games right back on them. I won't let you take advantage of me. I'll kill you before I let you take advantage of me."

The meeting had been arranged by a Chicago high school coach, a friend of Fleisher's. Garnett was arguably the best high school player in the country, a senior at Farragut who had transferred from Mauldin, S.C., for a variety of reasons, one of them a desire for more national recognition. He was living with his younger sister in an apartment, his father not on the scene, his mother back in South Carolina. His goal was to play big-time college basketball, but so far he hadn't scored high enough on the SAT or ACT to be eligible. This had prompted speculation that he would skip college and move directly to the NBA.

Garnett's coach wanted Fleisher, the agent for 18 NBA players, to give the kid some realistic advice. Fleisher's late father, Larry, had been the first head of the National Basketball Players Association. The son had been around basketball all his life. He knew that no player had jumped directly from high school to the NBA in 20 years, not since man-child Darryl Dawkins and journeyman forward Bill (Poodle) Willoughby had. Fleisher was pretty certain that his advice would be for Garnett to go to college, even junior college if he couldn't meet the Division I SAT requirement.

"I'm not signing anything," Garnett said at the beginning of their hotel meeting. "I'm not committing to anything. I don't owe you anything."

"Fine," Fleisher said.

They talked for a long while. Fleisher explained how hard it would be to make the NBA right out of high school, how college might be the best option. Garnett talked about his life in South Carolina, his life in Chicago, his hopes, his dreams. Garnett liked Fleisher's no-nonsense style. Fleisher liked the way the kid expressed himself, the way he thought. They agreed to meet again in two weeks, when Fleisher was back in town.

From the Vault: Remembering Kevin Garnett's first stint in Minnesota

"I'd never seen him play," Fleisher says. "I knew nothing about him. When I came back, I took him to the Lakeshore Athletic Club, this place where a lot of guys play. I wanted to put him through an NBA kind of workout to see how good he was."

The workout went badly. Fleisher ran the drills that NBA clubs run when they test potential draft choices. The kid was inexperienced, nervous. Frustrated. As he missed shot after shot, as his feet became tangled during the simplest tests, he looked toward another court, where a game was being played by college kids and men. "Look," he finally said, "just let me play in the game."

The kid joined the players on the other court, and the awkwardness disappeared. The shots went in the basket, one after another. The rebounds belonged to only one set of hands. The kid moved around the floor with the agility of someone a foot shorter. He dribbled and defended and picked and rolled. This was the dance he knew. "Ah," Fleisher said. "Yes."

You think about it now, and it's crazy. Four years ago nobody knew if this kid could play. Nobody. He has come from an uncharted nowhere to change the entire NBA, maybe change all of professional sports. A high school kid. He is the highest-paid athlete in any team sport, $126 million over six years. He will be the highest-paid player in the NBA for the foreseeable future, thanks to the new labor agreement, which came out of the lockout that delayed this season for three months and two days.

He was the final reason for the lockout. He signed a contract for so much money that the people in charge scared themselves into action. "Where will all this end?" they asked. They risked the future of the league, shut down operations. Because of him. He is the kid who broke the NBA bank.

Fleisher wanted other people to see what he had seen. He still wasn't convinced that the draft was Garnett's best option. The common guess was that some team at the bottom of the first round, top of the second round, would say, "Oh, hell, let's give the high school kid a shot." Fleisher didn't like that idea.

"If you go that low," he told the kid, "you're better off in college for a year or two. Sometimes picks that low don't even make the team. If you go to the NBA, you want to be a lottery pick."

To gauge the lottery teams' interest, the agent set up a special workout. Helped by the fact that a bunch of general managers, coaches and scouts were in Chicago to attend a predraft NBA camp, Fleisher sent invitations to the 13 teams with the highest picks. He borrowed the University of Illinois-Chicago gym and brought in Detroit Pistons assistant John Hammond to run the drills. Fleisher invented the procedure as he went along. No one ever had done anything like this.

On the day of the workout, a weekday, Garnett followed his normal schedule. He took his sister to school, then took himself to school. He went to his classes, then to basketball practice, then to his SAT cram course. Finally he went to the NBA workout, at about the time he usually took a nap.

"A guy from the neighborhood, Billy T, drove me to the gym in this old, beat-up car, this Huffymobile, whatever it was," Garnett says. "Billy T was all excited. He kept yelling at me that this was my chance, what I'd been waiting for all of my life, that I had to show these guys, that this was how I could climb out of the ghetto. It was all true. I knew it. I was so tired, though, I fell asleep on the way. I was just narked. I woke up and we were at the gym."

The general managers, coaches and scouts were sitting in the bleachers behind one basket. They formed a row of impassive famous faces.Garnett recognized Kevin McHale and Elgin Baylor and "that silver-haired guy who coached Miami before Pat Riley." (That guy would be Kevin Loughery.) There must have been 15, 20 famous people, all gathered to see him. The idea took his breath away. "A few of my boys had snuck in, too, but they were way at the top, keeping quiet so they wouldn't be thrown out," Garnett says. "Those were the only people in the gym."

"Do you want to stretch?" Hammond asked. Garnett pulled one foot back to touch his butt. He repeated the process with the other foot. That was all. He was stretched. He felt the same nervousness that he felt before big games.

The workout seemed as confusing as Fleisher's workout had. The drills seemed to be meant for smaller men. Dribble the length of the court with the right hand. Take a jump shot. Dribble back with the left hand. Take another jump shot. Do it again. He'd spent most of his basketball time in the spot reserved for all high school big men, under the basket. Spin left. Spin right. O.K. Dribble? Crossover? Jumper from the key? From the baseline? He felt awkward. He was breathing hard when he finished.

"No one had said a word, not one of those guys from behind the basket," Garnett says. "I was just standing there when one of them—the first voice—said, 'Jump and touch the box [above the basket].' I jumped and touched the box. 'Can he touch the top of the box?' another voice said. I jumped and touched the top of the box. 'Again,' someone said. 'Left hand,' another one said. 'Right hand.' 'Again.' 'Try it with a running start.' Suddenly they all were yelling out things."

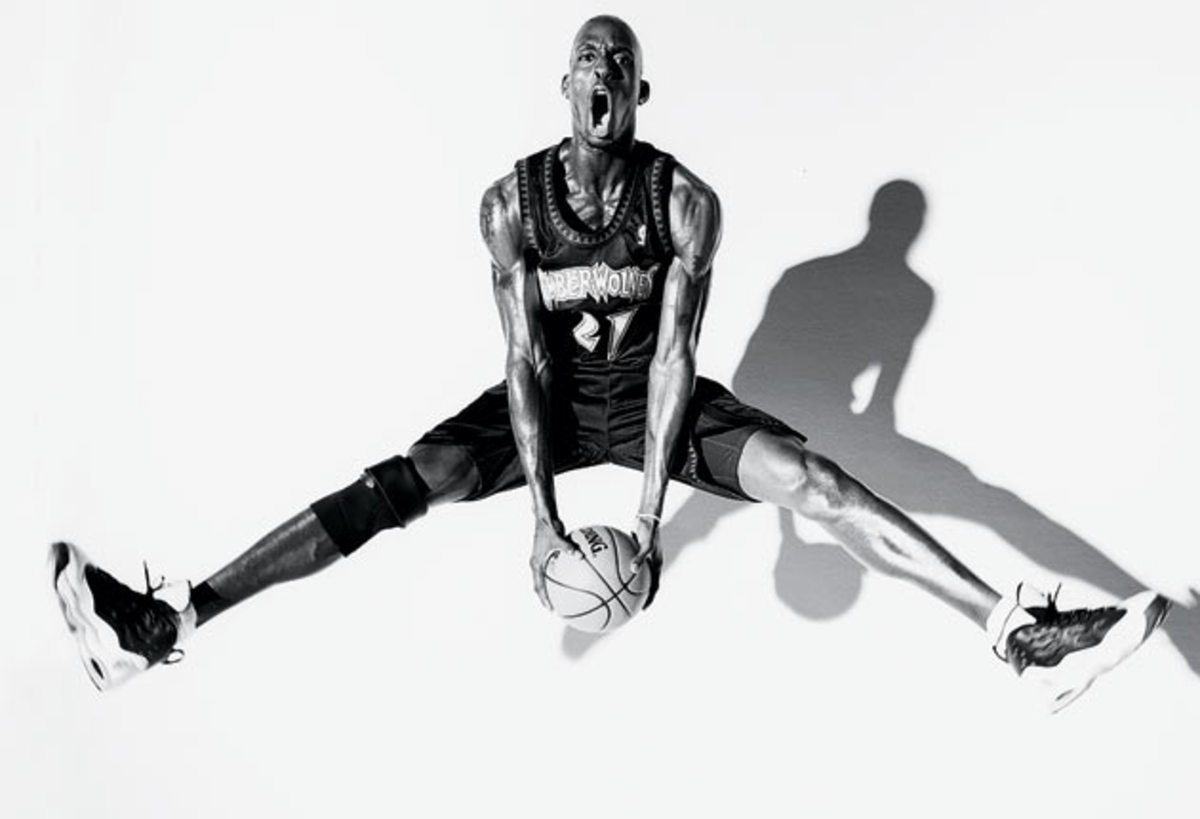

Garnett jumped and jumped and jumped some more. Somewhere in the middle of the jumping, he started shouting. Arrrrrrgh. He shouted with every jump. Arrrrrrgh and arrrrrrgh and arrrrrrgh. He jumped and shouted until the requests ended.

Trade grades: Nets ship Kevin Garnett to Wolves for Thaddeus Young

"When it was done, Kevin McHale came down to the floor and gave me a tip about my jump shot," Garnett says. "I'll always remember that. I thanked him, and then I walked back to the middle of the court while E [Fleisher] said goodbye to everyone. I lay down right in the middle of the court. I fell asleep for two hours. I was so tired." He awoke and his life had changed forever.

"I blew it," he told Fleisher, who had waited quietly in the empty, darkened gym.

"No, you didn't," the agent replied.

"I shouldn't have started shouting like that. They all think I'm a kid. Or uncontrollable. Or something. Why'd I shout? I blew it."

"You did fine," the agent said. "You did great."

He had seen the looks on the famous faces. They were impassive no more.

"We had no idea we were going to take him in the first round," McHale, vice president of basketball operations for the Minnesota Timberwolves, says. "I didn't even want to go see him. I thought it was a waste of time. Then we went, and Flip Saunders [then Minnesota's general manager] and I were in the car afterward, and we just looked at each other. I said, 'Wow, we're going to pick a high school kid in the first round.' It was that obvious.

"This was our first draft. Flip and I were both new. Our owner was also new. How do you tell him that the first thing he's going to do is sign this high school kid? I think we figured if it went bad, we'd just say, 'Hey, it was our first draft. We didn't know what we were doing.'"

The Timberwolves were a team badly in need of an image. The sixth-year expansion club never had made the playoffs. The excitement of simply being part of the NBA show was long gone. A succession of No. 1 draft choices had landed in the Twin Cities with a thud, from Pooh Richardson to Luc Longley to Christian Laettner to the latest, Donyell Marshall. McHale, the former Boston Celtics All-Star and University of Minnesota legend, had been hired to rebuild the operation.

Taking the kid was a risk, but taking anyone in the draft is a risk. Michael Jordan wasn't taken until the third pick. McHale and Saunders, who would soon become the Timberwolves' coach, went from being skeptics about Garnett to worrying whether he would still be available when they drafted fifth. "Had everyone seen what we'd seen?" McHale says. "We didn't know. We didn't know what to do. Should we announce right away that we were going to take him? Or should we lie, say we weren't interested, so no one made a trade to draft in front of us? I can't remember what we did. I think we lied."

The draft was held at SkyDome in Toronto. Garnett did not know what McHale was planning, but he knew something good would happen. Interest had picked up the day after his workout: phone calls, visitors, people asking him to take psychological tests and be interviewed. His picture was on the cover of Sports Illustrated, with the line READY OR NOT.... Garnett knew he was a hot commodity.

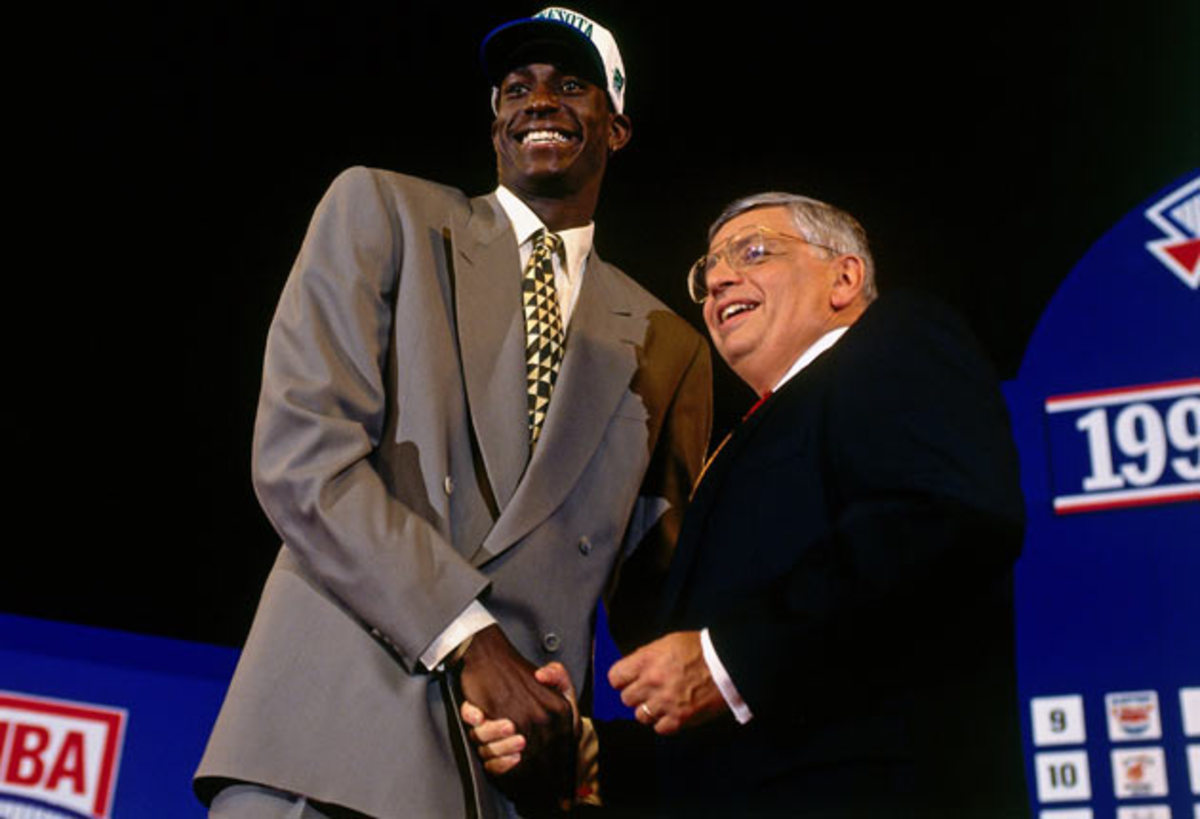

As he sat with family and friends, waiting to discover his fate, he felt overwhelmed. He felt as if he had stepped inside his own imagination. He had watched the draft for so many years on television, tall young men in new suits walking toward their glorious futures to standing ovations. This was where he had always wanted to be. This was where he was.

"Washington took Rasheed Wallace with the fourth pick, and then all of a sudden all these cameras were around me," Garnett says. "All these lights. I didn't know what was happening. Then I heard the announcement, 'With the fifth pick in the 1995 NBA draft, the Minnesota Timberwolves select Kevin Garnett.'"

He stood unsteadily, putting on the T-Wolves baseball cap that someone handed him. He accepted kisses, shook hands. He felt the weight of everything he ever had done in his life. He thought about the father he barely knew...about his mother cleaning lavatories, working the third shift as a domestic...about playing basketball on Beachwood Drive in Mauldin...about going across the street with a ball to pick up his best friend, Jaime (Bug) Peters, at six in the morning, ready to start, trying to beat the South Carolina heat...about playing in a neighbor's driveway until the neighbor came out, still half asleep, to stop the noise...about copying moves from Bug's Michael Jordan video, Come Fly with Me, kicking out the legs on the dunk, trying to look like the MJ silhouette on the Nike clothes...about Bug always telling him he was the best, the best on the street, in the neighborhood, the county, the state, the country...about playing against the big kids at Springfield Park...about high school in Mauldin...about high school in Chicago...about practice, practice, more practice...about work...about fate.

Garnett noticed Corliss Williamson of Arkansas, Ed O'Bannon of UCLA, good players he had watched on television. They were still sitting, awaiting the call. He was walking past them. How had this happened? He began to pray. "You can see it if you watch a film of the draft," he says. "My head is down, and my lips are moving as I walk. I'm saying a prayer of thanksgiving. Just as I reach 'Amen,' I look up, and I'm standing next to David Stern."

A strange thing had happened at the hotel an hour before Garnett left for SkyDome. The phone rang while his girlfriend, Corliss Strong, was adjusting his tie. The caller was his coach at Farragut, William (Wolf) Nelson. The coach wished the kid well and offered encouragement. Oh, yes, one other thing: Did the kid remember that last SAT test he had taken? Somehow the letter containing the results had fallen to the bottom of a pile on Nelson's desk. He had found the letter while cleaning the day before. Guess what? The combined score was 970.

"You passed," Nelson said.

The kid was stunned by the news.

"Well, it's too late now," he said.

Garnett's transition to the NBA, to Minnesota, to the Timberwolves, was easier than anyone had thought it would be. From the first day he arrived at the Target Center and found J.R. Rider shooting jumpers—"Hey, wassup?" "Wassup with you?"—the pro life was an extension of his earlier life. This was basketball. This was something he knew.

"People will always talk about 'the things you learn in the NBA,'" McHale says. "You know what you learn in the NBA? You learn how to play basketball. That's it. The only other thing I learned in my career with the Celtics was how to follow tall men through airports. You'd get your ticket from the trainer, and you'd follow the other tall men to the gate and get on the plane. It was like a herd of camels moving through the crowd. That was when we took commercial flights. Now we charter. You don't even have to learn how to follow tall men. You just learn basketball. The other stuff...you learn that yourself. You'd have to learn it wherever you went."

The team had considered some options, such as having Garnett live with a family, but he'd already been living on his own with his sister in Chicago. How would this be different? He created his own family, bringing Bug and another kid, Jerome, from South Carolina to live with him. He brought his girlfriend from Chicago. He rented a two-bedroom apartment. He added three dogs. Was that enough of a family? It even had a name, the OBF (Official Block Family), which included all the kids from Beachwood Drive in Mauldin, even the ones still back there.

"My idea is, I shine, you shine," Garnett says. "If I'm doing well and you're with me, you do well. I don't have a lot of friends. I have a lot of acquaintances, but that's different. Friends have been with you forever."

He had a fine mixture of exuberance and common sense. He was off on a basketball adventure. The Timberwolves had extra room on their charter flights, so they sometimes let members of the OBF come along. Garnett went shopping for cars with Fleisher, and Fleisher persuaded him to turn down the beauties of a Mercedes for a more reasonable Lexus. ("That idea lasted until he went to his first practice and saw the other cars in the parking lot," Fleisher says. "What is it with guys in the NBA and cars? That got him thinking Mercedes again in a hurry.") The OBF slid around the Twin Cities in the Lexus in the snow, listening to music, or went home and played video games.

Garnett didn't know much about Minneapolis except Kirby Puckett and Prince and...oh yeah, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, the Grammy-winning record producers for Janet Jackson and Boyz II Men and all kinds of singers. They were big, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis.

"One night, we stop in this grocery store," Garnett says, the excitement of the moment in his voice. "We're walking the aisles and there are Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis and their wives. We can't believe it. We're like...Jimmy Jam! Terry Lewis! Then Jimmy Jam spots us, and he says, 'Hey, Kevin, how are you?' He puts out his hand. He's a Timberwolves season-ticket holder, which I know already because I've seen him there. He's glad to meet me. He's amped. I can tell. I try to be quiet, polite. I say, 'Uh-huh, Uh-huh.' Then he gives me his card. He says to give him a call. I say, 'Uh-huh.' Then, after he leaves, we're all screaming, 'We met Jimmy Jam! He gave us his card!' Bug wanted to call him right then. I said no, we'd wait three days, until Wednesday, seven o'clock. Then I'd call."

He waited three days. Seven o'clock. He called. Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis became mentors, rich and important black men who could point the way. Garnett reports that Jimmy Jam's house is "as big as the Target Center."

"Kevin says I'm a father figure, but I don't know if that's right," Jimmy Jam says. "Although I'm old enough to be his father, I feel more like a brother. I'm not sure how to describe the relationship. He spends a lot of time in the house. We have what we call a media room, maybe six small TVs and a big one. Kevin likes to spend time there. We have a movie theater, too, that he likes. He spends the night sometimes, sleeps in the same guest room where Janet stays when she comes to town to record. His great dream is that sometime he'll be in bed and Janet'll come to town late at night and come into the room. I tell him to keep dreaming."

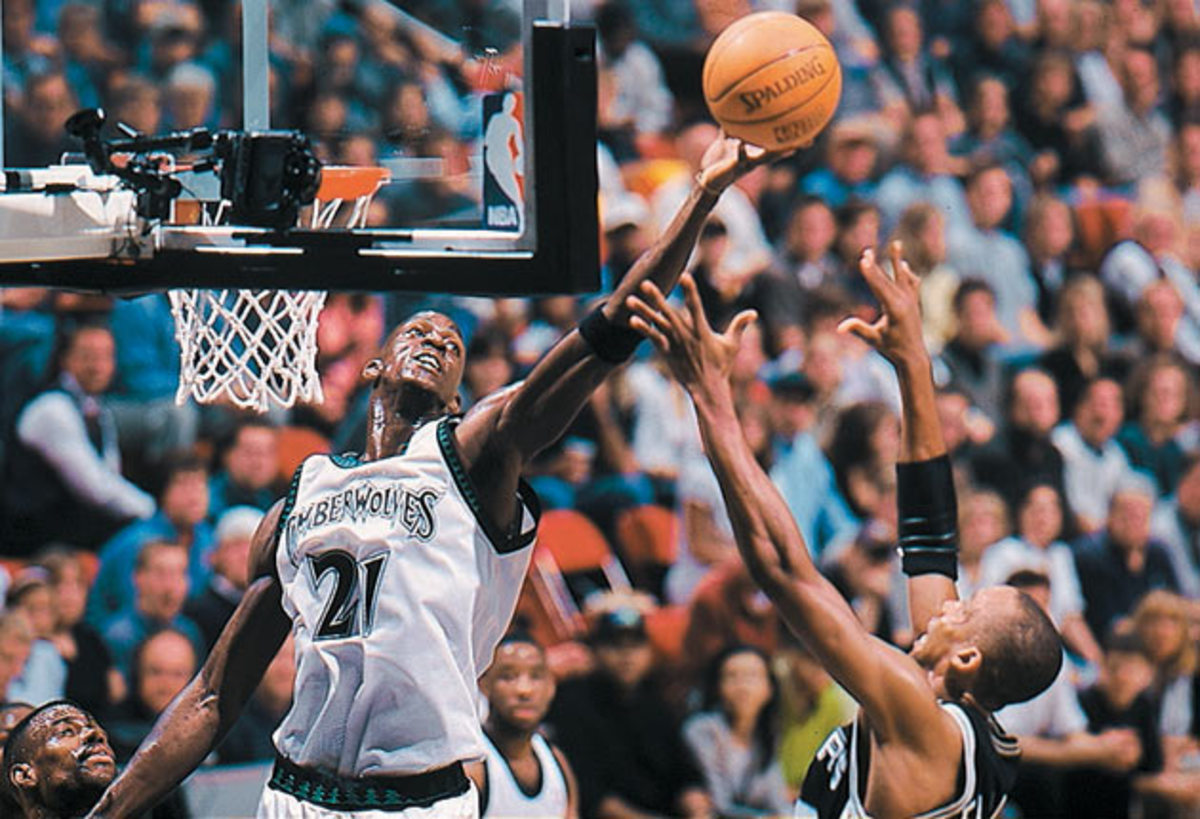

The T-Wolves' plan was to bring Garnett along slowly. Their first job was to decide what position he should play. His size and coordination enabled him to play...well, just about anywhere. On offense, he seemed best suited for small forward, where shorter men would have great trouble containing a 6'11" opponent. On defense? He could guard...well, it turned out he could guard just about anyone: centers, forwards, guards. Other teams tried to pound on him, overpower him, but he stood up to the punishment just fine. He played with a teenager's gusto, running everywhere, bounding, diving. He punched himself in the head when he missed foul shots.

McHale brought in Terry Porter and Sam Mitchell, a pair of NBA veterans, to share their knowledge with Garnett in the locker room. Mitchell was given the locker next to Garnett's. He also was given the starting job at small forward. Garnett came off the bench. "That lasted for about 35 games," Mitchell says. "Then I went to the coach and told him that Kevin should be starting. The reason was simple: He was better. I was playing against him every day in practice, and I knew how good he was. He was bigger than me, maybe quicker. He was better. It's no shame to say that."

In the final 42 games of the year the kid, as a starter, averaged 14 points, 8.4 rebounds and 2.26 blocks. He was the youngest player in the league. He still had not reached his 20th birthday when the season ended. In his second season, he blossomed.

Minnesota had acquired another kid in the first round of the draft, Garnett's friend Stephon Marbury, a point guard fresh from only one season at Georgia Tech, and now the team had the foundation of its operation. Inside and outside. The T-Wolves rolled, winning 14 more games than they had a year earlier, making the playoffs for the first time in their history. Garnett averaged 17 points, eight rebounds, more than two blocks per game. He played in the All-Star Game.

Minnesota looked set for a bright future. If, of course, it could keep its foundation intact. That was a problem. The kid was ready for some money.

You think about it, and everything is timing, is it not? You have to have something to sell, and you have to have someone who wants to buy. There has to be a demand.

No one ever had better timing than this kid. He caught the absolute crest of the financial wave and rode it farther than anyone in sports history had. He was in the right place, the right situation, offering the right mixture of performance and potential. He stimulated a bidding war. He had something to sell, and people wanted to buy.

Only two years into his career and he broke the bank. You think about it, and it's crazy. Crazy and wonderful.

The NBA was in the second year of a six-year labor agreement. A key part of the agreement was a wage scale for rookies. Burned by having signed rookies to extravagant contracts before they ever dribbled a basketball as pros, the owners had bargained for the wage scale. Every rookie signed a three-year contract for an amount determined by how high he had been taken in the draft. Garnett, taken fifth, signed for $5.6 million over three years.

At the end of the second year of the contract but before the start of the third, the player could sign a contract extension. This gave teams a chance to keep players they liked. At the end of the third year the player could file for free agency and make himself available to the highest bidder.

The Timberwolves wanted to keep Garnett. That gave him all the leverage. "I think the NBA had underestimated what would happen at the end of two years," Fleisher says. "I don't think the league knew how fast the money was going to go up."

"Every time you turned around, the benchmark figure went up," McHale says. "Each contract was for more money. It wasn't even about money anymore. It was about status." The most recent benchmarks had been established by free agents Alonzo Mourning and Juwan Howard. Mourning had signed with the Miami Heat for $105 million over seven years. Howard had signed with the Washington Bullets for $100.8 million over seven years. Minnesota owner Glen Taylor, a self-made millionaire in printing, electronics and marketing, looked at the numbers, swallowed hard and decided to get into the game. He offered Garnett $102 million over six years.

Garnett and Fleisher refused the offer.

"I couldn't believe it," Taylor says. "We came in high as a sign of respect, to make them know we were serious. When they refused, I didn't know what to do."

"It was a very, very good offer," Fleisher says. "We just thought there would be more if Kevin were a free agent a year later."

This was in August 1997. Garnett's refusal made headlines. He was 21 years old! He turned down $102 million! What was he thinking? Officials at the Minnesota State Fair took down a cardboard cutout of him, fearing that people would deface it. To get out of the spotlight, Garnett went to stay with Fleisher for a while, at his home in Westchester County, north of New York City. He played basketball with Fleisher's 13-year-old son in the driveway, spent time on the Internet talking to strangers under an alias. Fleisher took the heat.

"Minnesota didn't have to sign him," Fleisher says. "They could have waited another year, then tried to sign him as a free agent. They had to guess what the market would be then, but if they guessed wrong, they were going to lose him."

"I thought he was gone," McHale says.

Taylor went back to the numbers. How much could the Timberwolves pay? Taylor made big deals in business. He wanted to make this deal. He was convinced he had to. The credibility of the franchise was at stake. He had to figure out the possibilities.

"Number one, I knew I'd have to overpay, because we're a small-market city," Taylor says. "Eric pointed out the economic advantages of playing in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles. I understood that. I had to try to balance some of that.

"Number two, the deal made business sense. If our club had had a history of success, I probably wouldn't have pursued it. Here I was, starting out, telling people, 'Trust us, we'll get it done.' We're telling the fans, the sponsors, that we're serious. This was the wrong time for us to lose Kevin. He's young, he's a leader, he has charisma. He's the type of person who can lead a team to a championship."

The deadline to sign was Oct. 1. Negotiations between Taylor and Fleisher resumed a week before that. The talks went down to the last day. One hour before the deadline an agreement was reached. Fleisher called Garnett at Jimmy Jam's house. They were listening to the new Janet Jackson album, The Velvet Rope. "We've got a deal," Fleisher said. "You have to come down and sign it now."

"Hey, we're listening to Janet's album," the kid said. "Could we do it a little later?"

"Kevin...."

Six years, $126 million. The Minnesota Star Tribune estimated that if the money were laid out in $1 bills, end to end, it would stretch 12,113.3 miles, roughly halfway around the equator.

"I said, early on in the lockout, that this was the contract that changed the landscape," NBA deputy commissioner Russ Granik says. "This was the one where owners said something had to be done. The magnitude of Garnett's contract indicated the whole thing was out of control."

"I think most owners looked at the contract and said, 'This is where it's going,'" Indiana Pacers president Donnie Walsh says. "There was no leverage on the side of the team. None."

"You had a new, inexperienced owner overpaying to keep a star," another owner says. "That's how most owners saw it. At the same time, though, they looked at their own situations. What was going to happen when the next class of rookies came up for extensions, Allen Iverson in Philadelphia, Antoine Walker in Boston?" The owners took advantage of an option to reopen the agreement after three years, and they shut down operations until a new contract was reached. Under the new one, there is a cap on salaries for all players. If Garnett were to sign now, the maximum he would receive would be $71 million over six years. He made roughly $60 million more by signing when he did. No, he made more than that. Much more.

"He's grandfathered into the agreement," Fleisher says. "When he comes up for his next contract--when he's 28, at the top of his ability--he can re-sign for 105 percent of his salary in the preceding year. His salary that year is going to be [$28 million]."

The contract went into effect when the NBA resumed action in February. (Garnett played last season on the third year of his original deal.) The kid is having a terrific season. At week's end he was averaging 20.8 points, 10.3 rebounds and 4.4 assists per game. He has had to handle some serious alterations to the team's foundation, though. Free-agent forward Tom Gugliotta left in the off-season for the Phoenix Suns. Marbury, partly because he knew he forever would be No. 2 in the Minnesota operation, partly because he wanted to get back to the East Coast, forced his way to the New Jersey Nets in a midseason trade. The kid, working with replacements such as forward Joe Smith and point guard Terrell Brandon, has kept the T-Wolves rolling. Through Sunday they were 22-23 and had a chance to make the playoffs for the third straight year.

Seldom seen on television due to the networks' fascination with brand-name teams such as the Los Angeles Lakers, New York Knicks and Utah Jazz, Garnett has become a modern rarity: an underhyped superstar. He is an undeniable force on the floor, an animated presence on offense and defense. In a game against the San Antonio Spurs in February he guarded David Robinson, Tim Duncan, Sean Elliott and Steve Kerr at different times. Garnett might be the most versatile player in basketball. He even has grown an inch, to 7 feet, although he still is listed at 6'11".

Garnett's success straight from high school encouraged other kids to go to the NBA straight from high school. Two kids followed in 1996, led by Kobe Bryant of the Lakers. One more went into the league from high school in 1997 and three in '98. It is not the greatest trend. Even Fleisher would encourage most kids to go to college.

"Kevin is an aberration," Fleisher says. "I've never seen anyone else his age with his maturity, his skill level, his enthusiasm and his size. The mistake most young men make is in thinking they're going to have the same growth level as Kevin. I suppose Kobe finally is breaking through, but the effect Kevin has on a game is much greater than Kobe's. Kobe isn't 7 feet tall."

Garnett owns a house now, a bigger place for the OBF to reside, and is planning an even bigger house. He is using Jimmy Jam's architect. He owns assorted cars and toys. When neighbors complained about the noise made by his go-karts, he bought 14 acres in the woods. He also bought off-road ATVs for his friends. I shine, you shine. He likes to watch Bug and Artie and the other guys buzz around. After a day of practice, he goes to watch them play basketball. He says they won't let him play with them because he's "too bossy."

During the lockout the OBF took some trips around the country. The members called the trips Operation Go-Hard. They would fly from Minneapolis to Las Vegas for two days, then to Los Angeles for two days, over to New York for two days, down to Atlanta for two days, maybe stop off in South Carolina for two days, then come home. Garnett says that for this summer they're thinking of expanding the itinerary. Maybe Paris. Maybe Italy.

He has hired advisers to handle his money. He says he has "men watching the men who are watching the men who are watching the men and, like the line in the movie Casino, the eye in the sky watches everyone." He is the eye in the sky. He gets advice from Jimmy Jam. He gets advice from T-Wolves owner Taylor.

It is an adolescent's fantasy life. If Garnett had gone to college, he would be a senior now, heading toward graduation in June, at which the commencement speaker might advise the class on how to achieve success. The kid has figured it out for himself.

"You must have changed in these four years," a reporter says to Garnett one afternoon at the Target Center.

"Yeah," he replies, "I think I've changed, but the one thing I've always tried to be is myself. I think people respect a genuine person. I think I've become more of a leader. I think I've become more hungry about basketball, wanting to win. I think I've become more direct with people. I think we all change as we get responsibility, as we grow."

He looks at the empty arena. "Come back four years from now," he says. "It'll be interesting to see how I've changed by then."

He is 22 years old.