Do You Know Me? Few recall Earl Lloyd was the first black NBA player

Editor's note: In honor of Earl Lloyd, the man who broke the NBA's color barrier. This story first appeared in the November 28, 1994 edition of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

On Jan. 19, 1988, Earl Lloyd was relaxing in his immaculate four-bedroom apartment in downtown Detroit when his phone began to ring and never stopped. Former schoolmates and friends were calling, and they all wanted to know the same thing: "Was that really you?"

They had been watching the TV game show Jeopardy!, and one of the questions—or, rather, answers—came from the category SPORTS: "Jackie Robinson broke baseball's color line; Earl Lloyd was the first black to play in this pro league." The first contestant shot back: "What is the NFL?" Sorry. It wasn't the first time that Lloyd's place in basketball history had been forgotten. The second contestant, choosing between the NHL and the NBA, guessed correctly.

On Oct. 31, 1950, in an old gym in Rochester, N.Y., Lloyd made history simply by stepping onto a basketball court. In an otherwise meaningless game between two now defunct teams, Lloyd's Washington Capitols lost to the Rochester Royals 78-70 before all of 2,184 fans at the Sports Arena.

Lloyd went on to play nine years in the NBA, first with the Capitols, next with the Syracuse Nationals, and finally with the Detroit Pistons before retiring as a player in 1960.

"When people check into Black History Week and honor the great black heroes, Earl should be one of them," says Johnny (Red) Kerr, a former teammate of Lloyd's and now a TV analyst for the Chicago Bulls. "People know who Jackie Robinson is. Why don't they know about Earl Lloyd?"

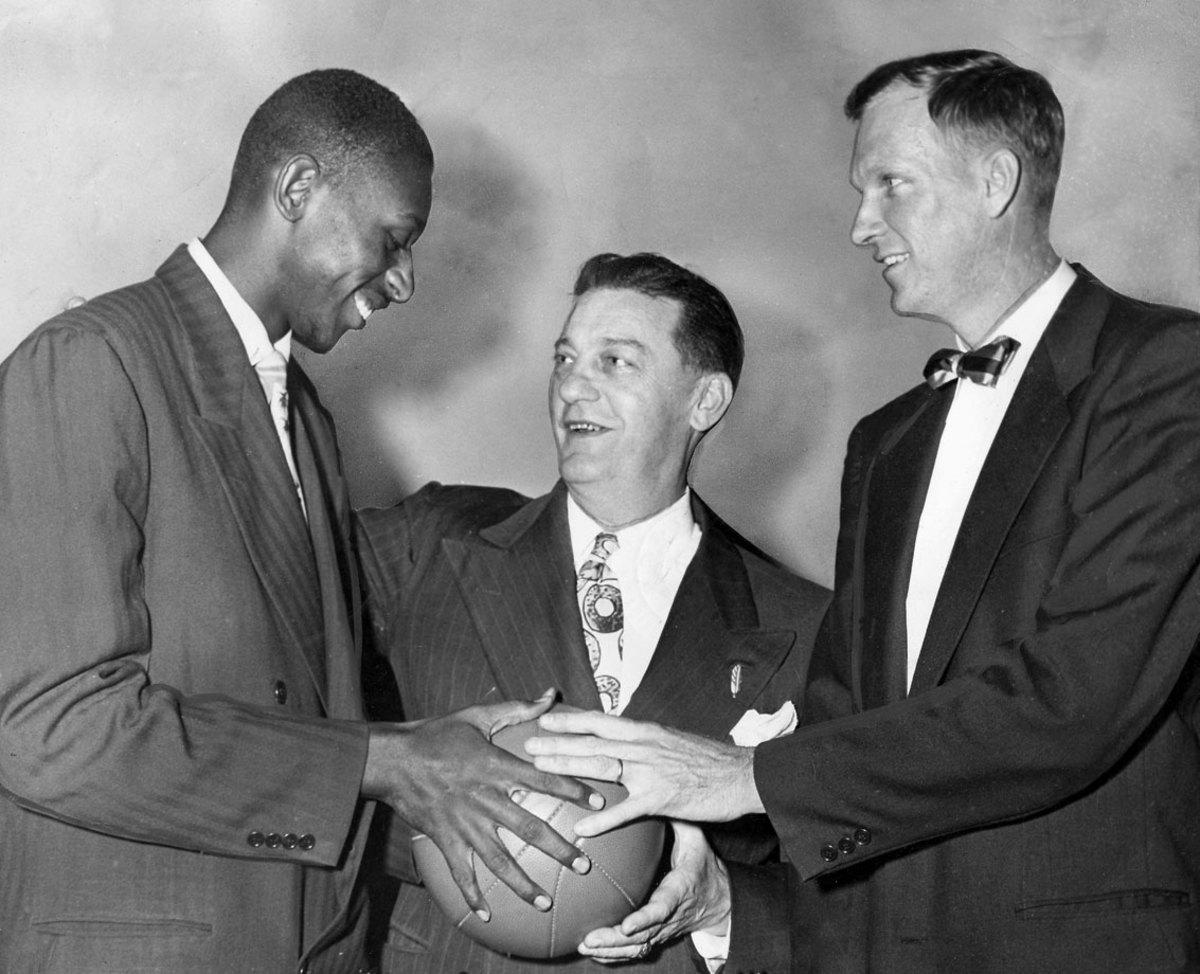

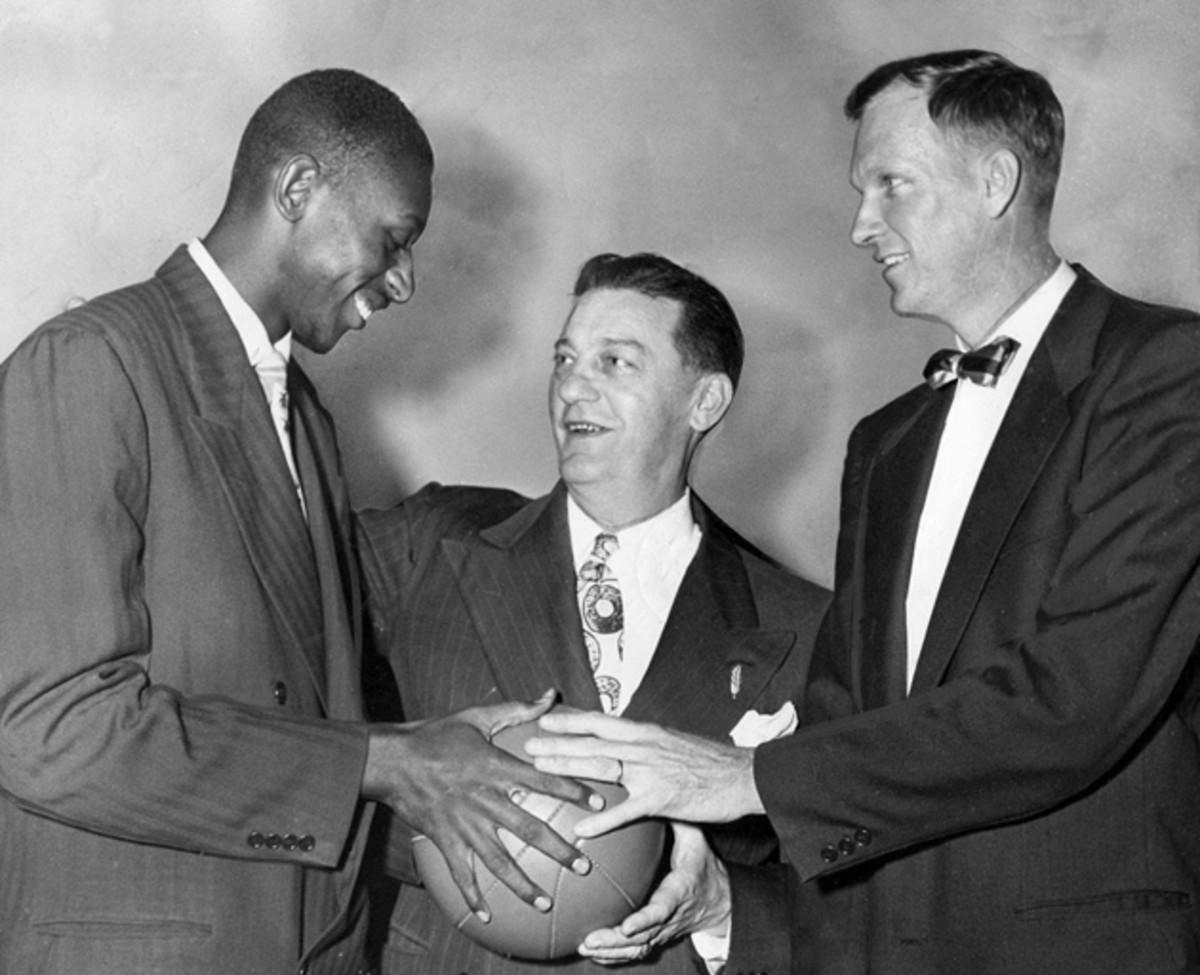

One reason is that Lloyd was one of three African-American players to enter the league in 1950. Nat (Sweetwater) Clifton, a forward who had played with the Harlem Globetrotters for two years before joining the New York Knickerbockers, was actually the first black to sign an NBA contract. Chuck Cooper, a forward from Duquesne, was the first to be drafted, when Boston Celtic owner Walter Brown shocked his fellow team executives by selecting Cooper in the second round. But it was Lloyd, a ninth-round pick by Washington, who was the first to play in an NBA game—thanks to what Lloyd himself calls a "scheduling quirk." (The Celtics played their season opener the following night.)

Today Lloyd, a youthful 66-year-old with a still-imposing 6'6", 270- pound frame, does community-relations work for Dave Bing, the former Detroit Piston star who is now CEO and chairman of The Bing Group, a steel and auto parts manufacturing company in Detroit.

Earl Lloyd Tribute

Earl Lloyd, a forward known for his defense who played collegiately at West Virginia State College, was selected in the ninth-round of the 1950 NBA Draft by the Washington Capitols.

Earl Lloyd made his NBA debut on Oct. 31, 1950, as a member of the Washington Capitols. He was one of four African American players to play in the league that season. However his team disbanded after seven games.

Earl Lloyd played nine seasons in the NBA, six with the Syracuse Nationals, missing the 1951-52 season to serve in the U.S. Army.

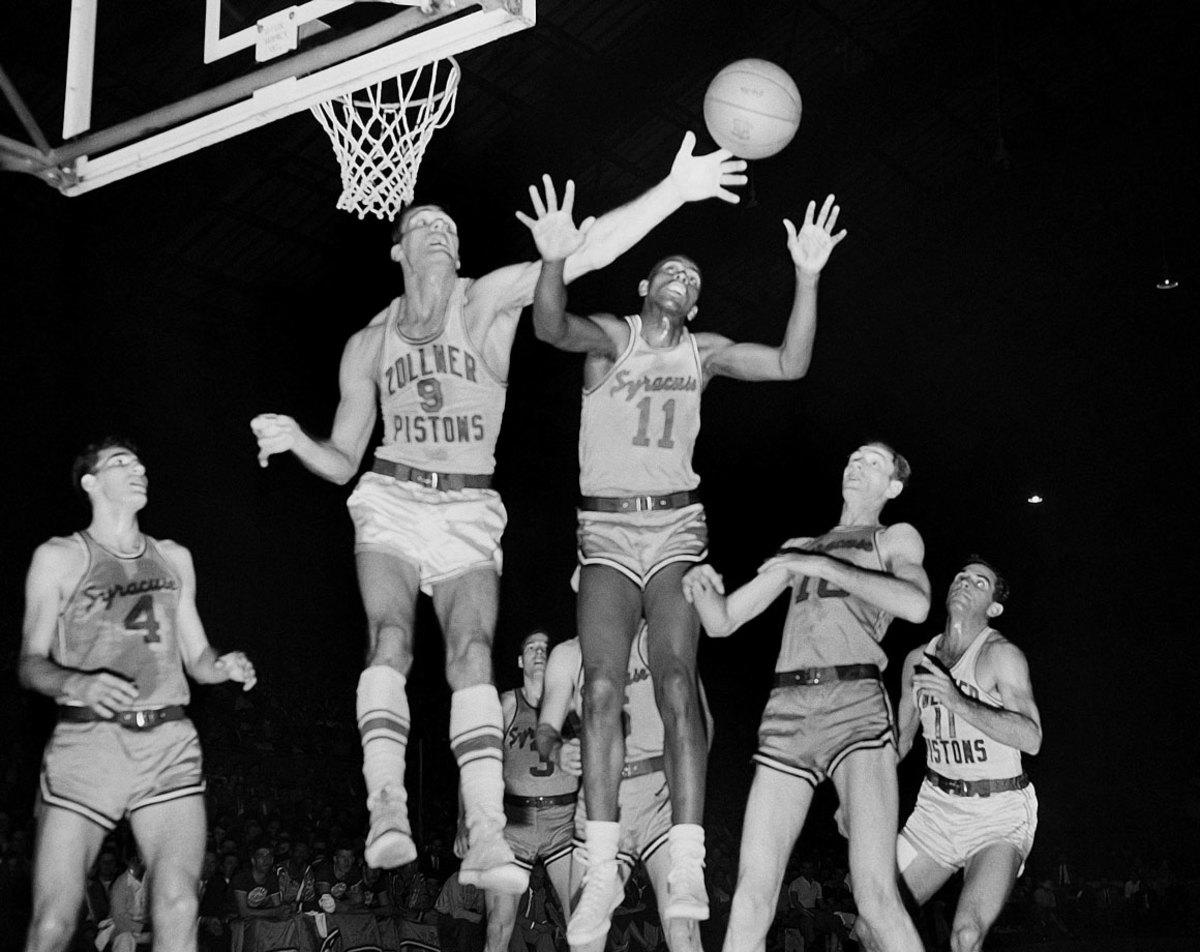

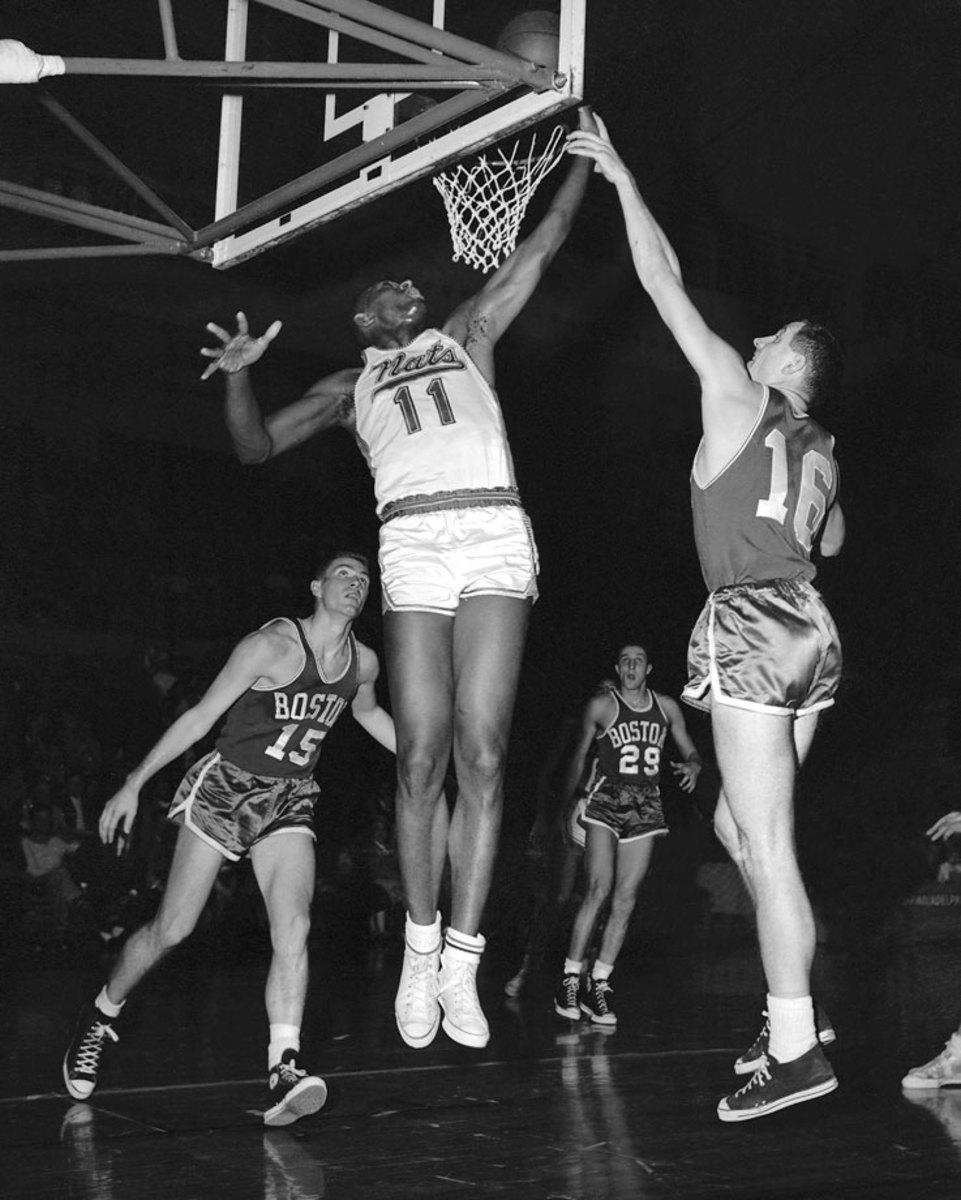

Fort Wayne's Mel Hutchins and Syracuse's Earl Lloyd reach for the ball during the 1955 NBA Finals. The Syracuse Nationals won the series 4-3 over the Fort Wayne Pistons.

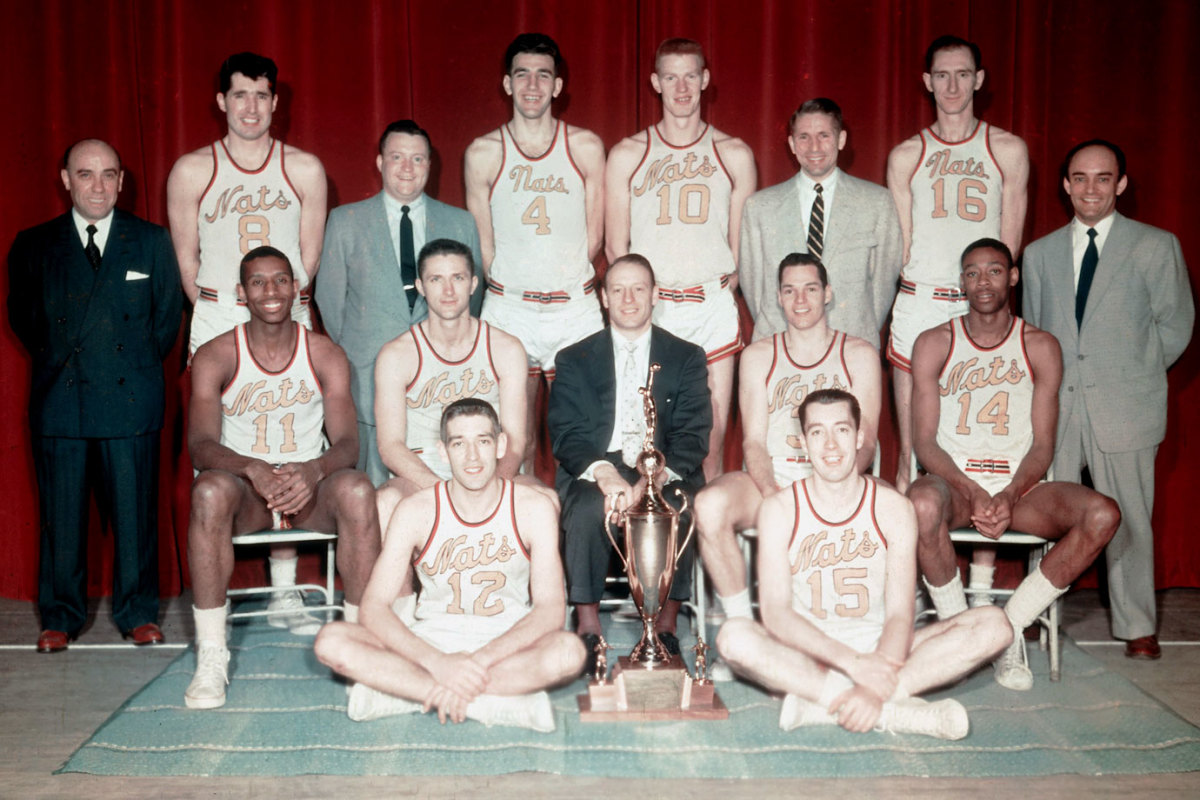

The World Champions of Basketball Syracuse Nationals pose for a team portrait in 1955. Earl Lloyd (11) and Jim Tucker (14) were the first two African Americans to play on an NBA championship team.

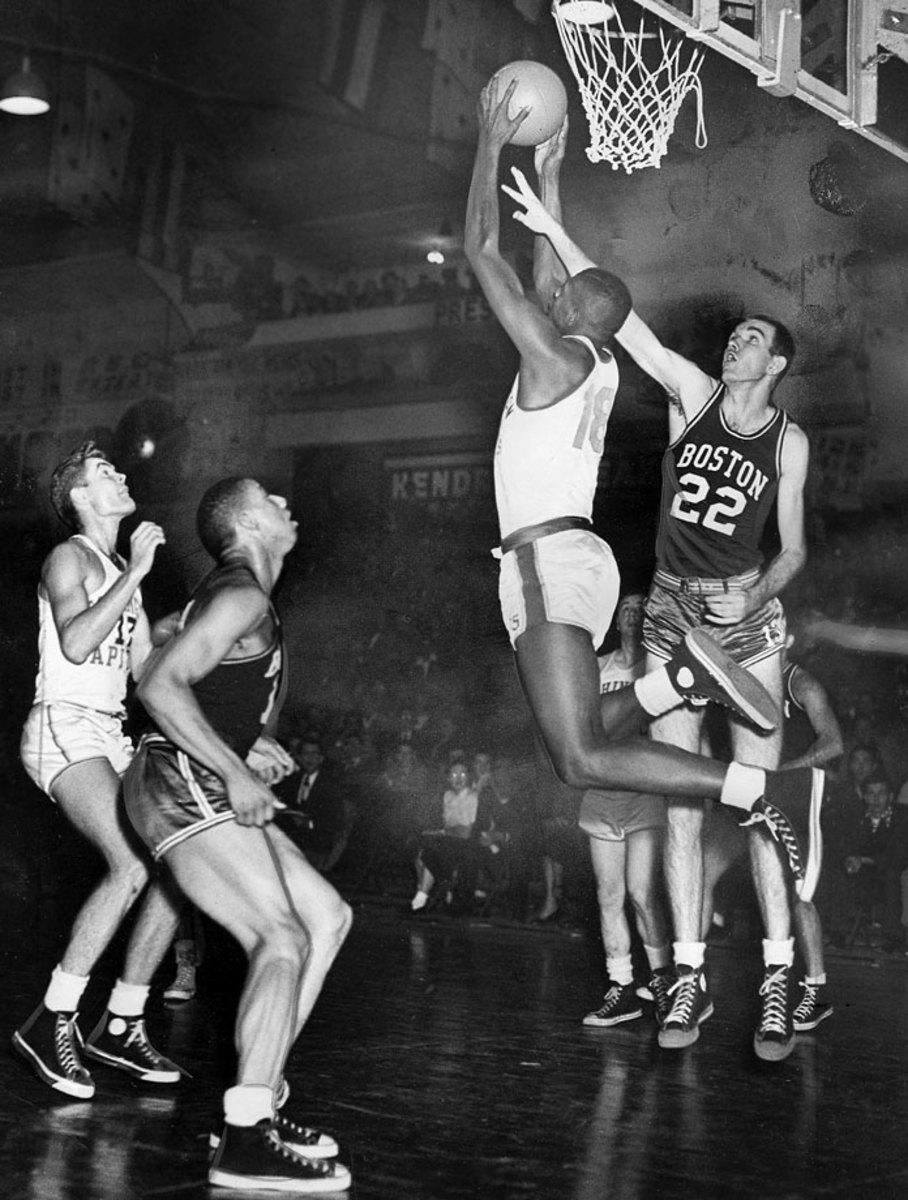

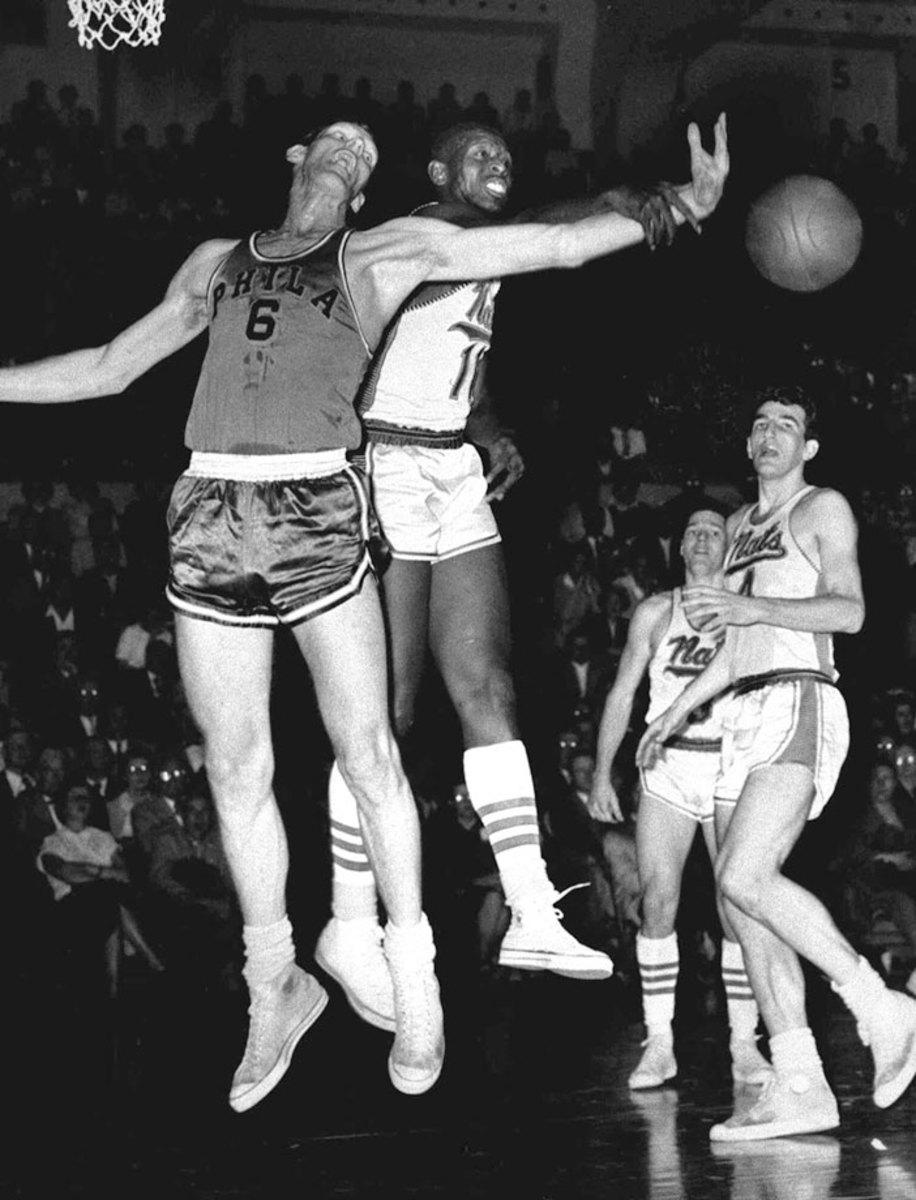

Earl Lloyd shoots a layup against Tom Gola during a game between the Syracuse Nationals and Philadelphia Warriors in 1956.

Earl Lloyd blocks a shot by Neil Johnson during a game between the Syracuse Nationals and Philadelphia Warriors in 1956.

Earl Lloyd shoots a layup against Jack Nichols during a game between the Syracuse Nationals and Boston Celtics in 1958.

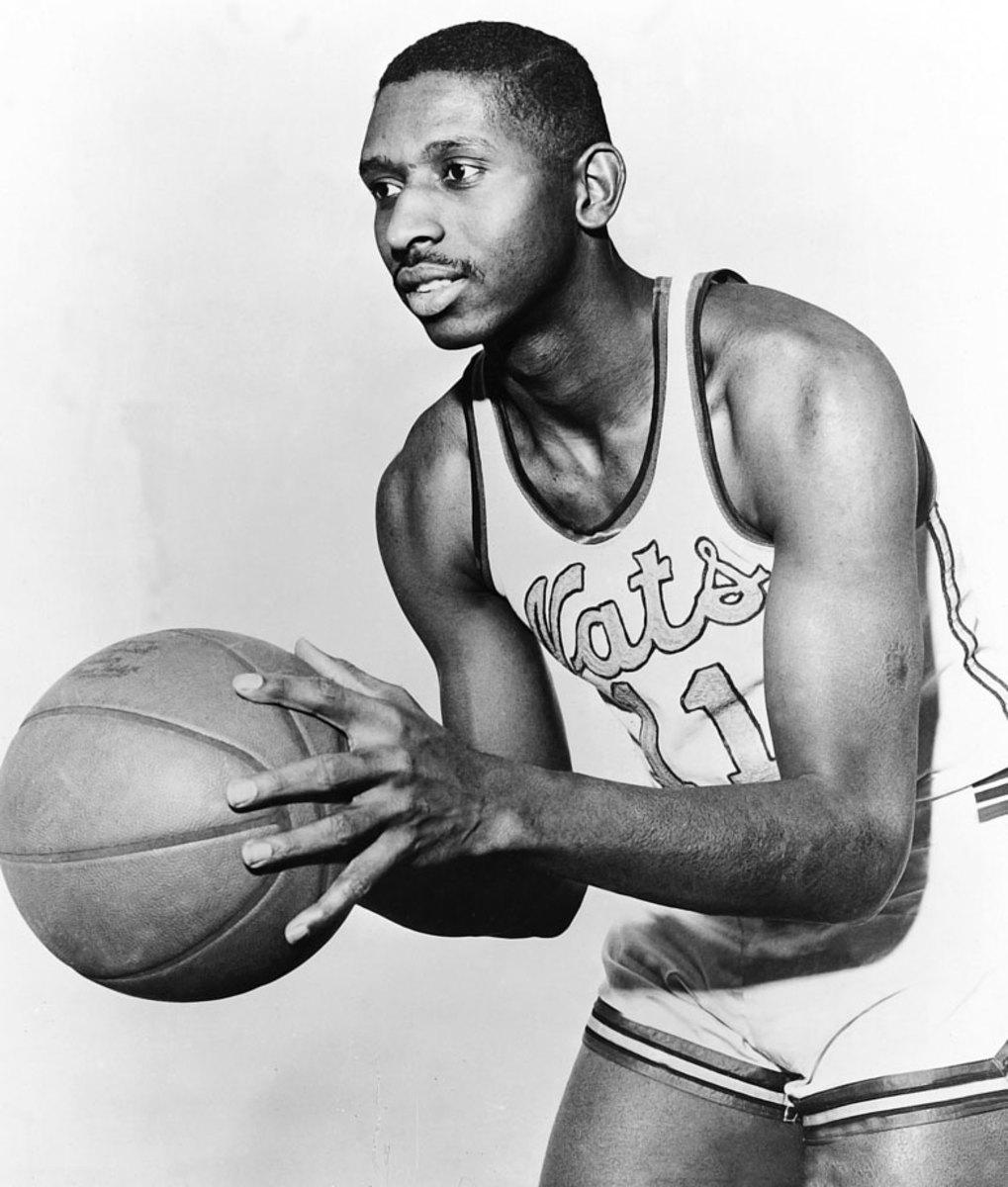

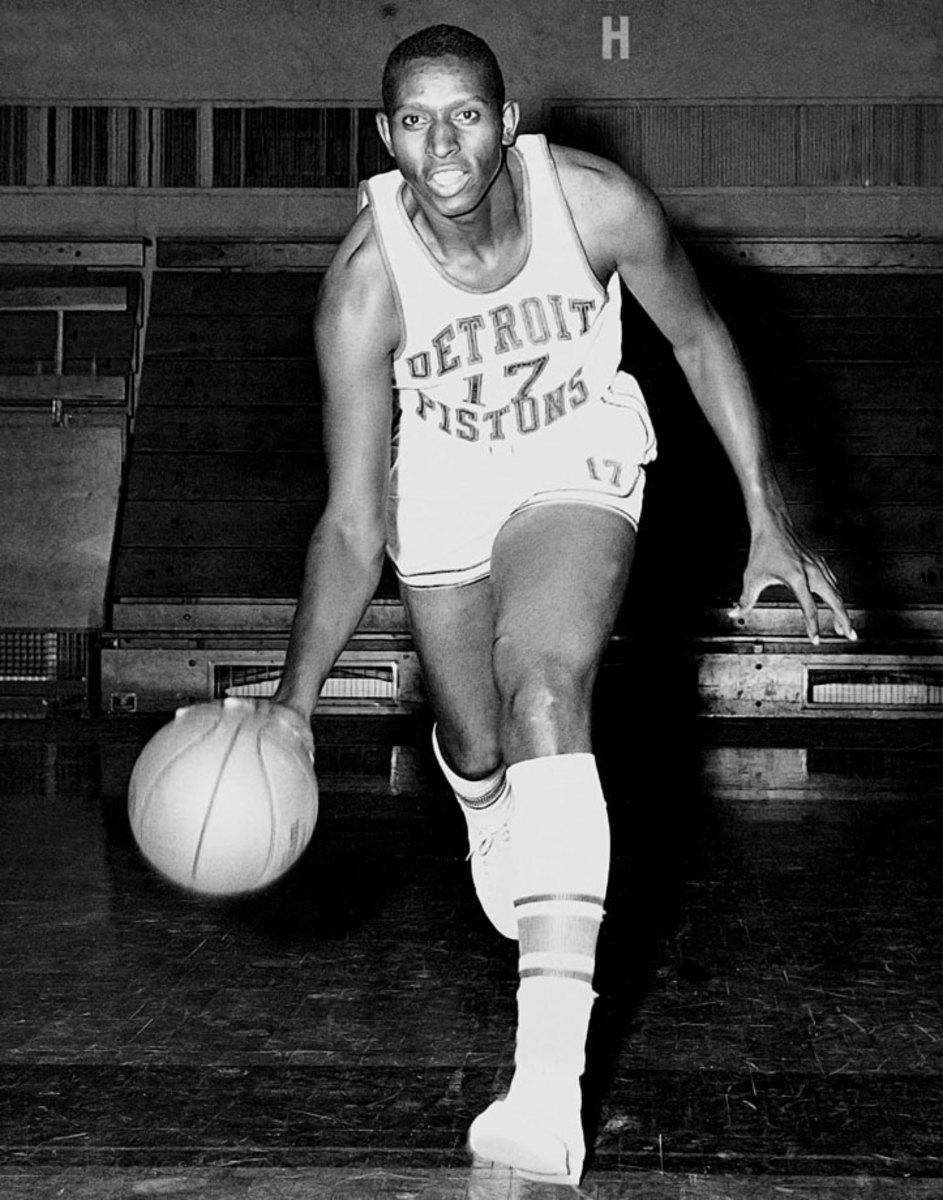

Earl Lloyd of the Detroit Pistons poses for a portrait in 1959. Lloyd played two seasons with the Pistons before retiring in 1960.

Earl Lloyd also became the NBA's first black assistant coach in 1968 with the Detroit Pistons and later become one of the league's first black head coaches, also with the Pistons.

Earl Lloyd poses for a portrait in 2000. For his career, he averaged 8.4 points, 6.4 rebounds and 1.4 assists, scoring 4,682 points in 560 games. The forward's best season came in 1954-55, when he averaged 10.2 points and 7.7 rebounds, both of which were career highs.

Earl Lloyd shakes hands with Bill Russell, the first African American head coach, during a Symposium at the Cook Convention Center in Memphis in 2003.

Bob Lanier, Will Robinson, Earl Lloyd and Dave Bing pose for a picture at halftime of Game 2 of the Pistons-Magic first round series during the 2003 NBA Playoffs in Auburn Hills, Mich.

Earl Lloyd was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame as a contributor in 2003.

Earl Lloyd and Dolph Schayes are honored at a 76ers-Warriors in 2005 at the Wachovia Center in Philadelphia.

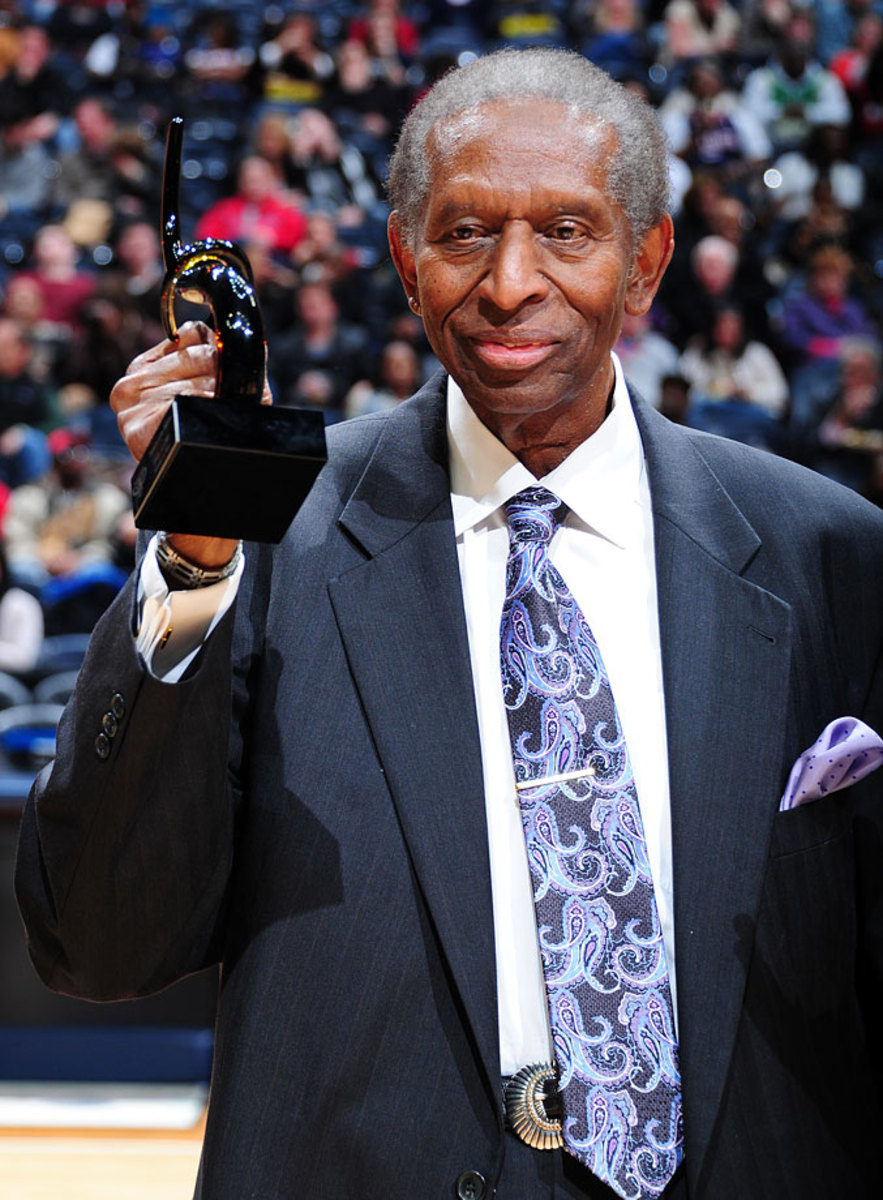

Earl Lloyd is honored to celebrate black history month during a Hawks-Heat game in Feb. 2012 at Philips Arena in Atlanta.

. "He took orders from me; now I take orders from him," Lloyd says with a laugh.

He began working for Bing last year, after spending eight years as an administrator in Detroit's public school system, finding jobs for dropouts and beleaguered graduates. Lloyd hasn't been involved in basketball since 1972, when he was fired as coach of the Pistons seven games into the 1972-73 season. He rarely attends NBA games, and he is reluctant to gripe about the discrimination he encountered during his playing days.

Washington's second game of the 1950-51 season was at home against the Minneapolis Lakers. Lloyd's parents, who were sitting in the stands, were subjected to countless racist remarks, including those from fans who wondered aloud if ''that n-----'' could play. Bigotry would follow Lloyd throughout his career in the NBA, but he makes it clear that not once did a teammate or opposing player belittle him with a racial slur. The fans, however, more than made up for it.

''Indianapolis, Baltimore, Fort Wayne ... tough towns, man,'' Lloyd says. ''When you went to Fort Wayne to play, you had to do some emotional yoga to get ready because you knew what was coming.''

Kerr remembers an incident that took place in Fort Wayne when he and Lloyd were walking off the floor after a win. "I had my arm around him, and we were celebrating," Kerr recalls. "And some guys just spit on us. And it wasn't because we beat them. They disrespected Earl."

Lloyd had learned years earlier, growing up in segregated Alexandria, Va., that whites weren't going to welcome him with open arms. He didn't even sit next to a white person until he was 21, the same year he graduated with a degree in education from West Virginia State, an all-black school.

"You wanted to lash out at somebody," he says about his playing days. "But you can't jump on fans."

Instead Lloyd kept his composure by remembering how his mother had taught him to deal with hatred: Consider the source. ''Stupid people do stupid things,'' she told him. ''Small people do small things. Don't let them get to you.''

In some cities Lloyd wasn't allowed to stay at the same hotels or eat at the same restaurants as his teammates. Instead, he went to places where he knew he would be welcome -- jazz clubs. On the road he carried the music magazine Downbeat to read about the local hot spots.

Although nicknamed the Big Cat because of his size and quickness, Lloyd was never an All-Star -- he averaged 8.4 points and 6.4 rebounds during his career. But he was the kind of player coaches dream about, someone who took pride in playing defense. Night after night he was assigned to the opposing team's highest-scoring forward, a player such as the Minneapolis Lakers' Elgin Baylor or the Celtics' Tommy Heinsohn.

''He really sacrificed,'' recalls Gene Shue, the director of player personnel for the Philadelphia 76ers and a former teammate of Lloyd's on the Pistons. ''He was a great defensive player, and he was always setting screens and doing whatever it took to make you win.''

Lloyd and his fellow Nationals reaped the benefits of their efforts when they won the 1954-55 NBA championship by beating the Fort Wayne Pistons in seven games. The victory was all the more significant because Lloyd and Jim Tucker -- a 6 ft. 7 in. forward from Duquesne -- became the first African- Americans to win an NBA title. Still, those finals weren't exactly as big as last season's clash between the Knicks and the Houston Rockets. ''We played all the away games for the finals in Indianapolis, because the American Bowling Congress had scheduled its tournament in Fort Wayne's gym,'' Lloyd recalls. ''That tells you right there the impact that basketball had.''

[daily_cut.NBA]

It also helps explain why Lloyd's debut 4 1/2 years earlier drew so little attention. In fact, on Nov. 1, 1950, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle did not even mention that the NBA color barrier had been broken the night before. ''Sometimes there wasn't anybody to cover the games,'' Shue says. ''This was basketball in its infancy.''

The same wasn't true of baseball when Robinson made his debut in 1947. Lloyd, who idolizes Robinson, says his plight paled in comparison with the abuse Robinson suffered. ''Baseball was the grand old game. People were vehement about it,'' Lloyd says. ''Jackie even had to fight his own teammates.''

But for all of Robinson's troubles, at least he was recognized. The same can't be said for Lloyd. ''Players today don't care about history,'' says Bing, who played in seven All-Star Games during his 12 years in the league. ''It's all about today -- all about money. A lot of them have screwed-up values.''

Detroit rookie forward and emerging star Grant Hill heard of Lloyd only recently. ''As a student of the game and a former history major (at Duke),'' Hill says, ''I am a bit embarrassed that I didn't know who he was.''

In August, Earl and his wife, Charlita, returned to his home state to visit the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame, in Portsmouth. Earl had been enshrined there on May 7, 1993. Staring at his plaque more than a year later, he fought back tears. ''As a kid, that honor would have been unheard of,'' he says. ''It'll be there for an eternity.''

Meanwhile, in Detroit, Lloyd is still forgotten. On Dec. 14 the Pistons will celebrate Grant Hill Jersey Night. Jan. 20 will be Grant Hill T-Shirt Night. But there are no plans for a night to honor the man who both played for and coached the Pistons, the man who helped pave the way for Hill.

''The league's emphasis has been on selling basketball today, instead of the past,'' says Joe Dumars, the veteran Piston guard. ''They've been so successful. But there should be a balance.''