A Giant Shadow: Did Wilt Chamberlain have a son? Levi may be living proof

This story appears in the March 9, 2015 edition of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

Aaron Levi wanted to know who he was, where he came from, where he belonged. His curiosity was born of a feeling that he was different. He was a biracial child adopted by a white couple when he was six months old. Taller than his schoolmates at almost every age, he was 6' 5" by the time he left high school. He was also gay—and, he said, desperately trying to hide it.

At South Eugene (Ore.) High in the early 1980s he passed himself off as a New Waver, shaping his hair into a flattop, listening to British reggae. He loved to draw, and he began to identify as an artist. Because of his height and color, he said people assumed that he played basketball. But he had little interest in sports.

Classmates often asked him, “What are you?” Some figured he was Greek, Italian or Middle Eastern. When he grew older and moved to Northern California to attend art school, a few people spoke to him in Spanish, assuming he was Latino. He noticed how African-Americans gave him a brotherly nod.

He imagined his biological parents as romantic partners happy to have given him flesh and blood. He learned later, through his own experience, the pain of the adoption process, both for himself and for his birth mother. “When you are adopted,” he said, “rejection is woven into your DNA.”

Still, he knew he was lucky. He said he had a happy childhood in Oregon with loving adoptive parents, though they divorced when he was still in grade school. Don and Harriet Levi adopted four children of color during the Sixties, including a daughter they named Naema in honor of a John Coltrane ballad. They told Aaron what they knew about his biological parents: that his mother was white and his father black and tall, at least 6' 10". That’s all that the Santa Clara County (Calif.) Social Services Agency had told them.

For Aaron the mystery began there. What in his genes might explain his love of all things British (Diana Rigg and The Avengers, Angela Lansbury, the magical sound of a British accent)? When his younger brother had a football mural painted on his bedroom wall, nine-year-old Aaron asked for Mary Poppins on his, and there she was, flying away with her umbrella. As a teenager Aaron bought the cast album of the musical Annie and heard “Maybe,” a wistful song in which young orphans wonder who their biological parents are and where they might be. It reflected his own yearnings: “Betcha they’re good/Why shouldn’t they be?/Their one mistake/Was giving up me!”

In 2003, nearing 40, Levi finally began to search for answers to his questions. When he found and spoke with his biological mother, he heard in her accent that she was British. But that wasn’t the most surprising revelation. Levi was told that his biological father was the most transformative player in pro basketball history and one of the most transcendent athletes of the 20th century.

Out of the blue I received an email from Levi in February 2014. The subject line read, “In regards to Wilt Chamberlain.”

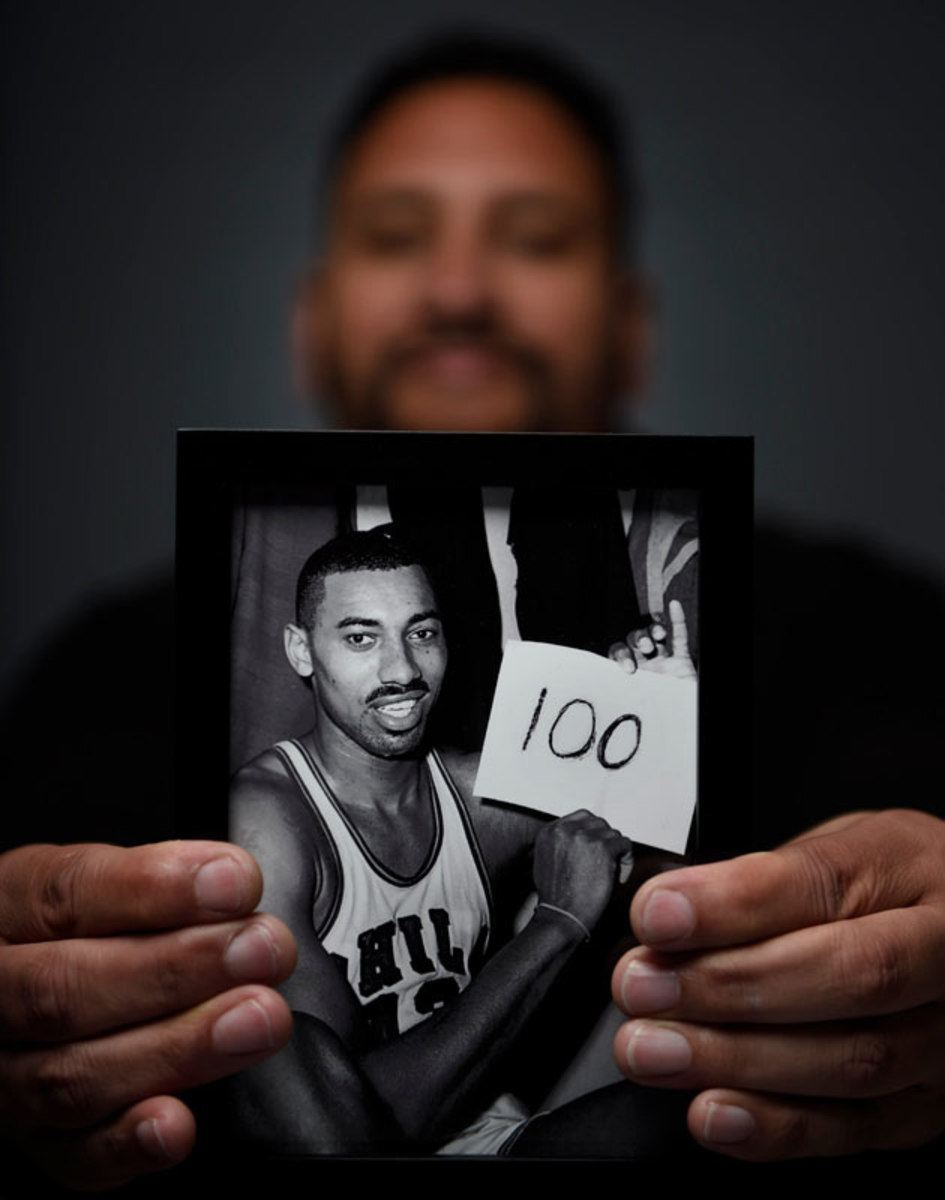

I’ve often received emails about Chamberlain in the decade since the publication of my book WILT, 1962, a narrative about the night he scored 100 points against the Knicks in Hershey, Pa. Chamberlain, the Philadelphia Warriors’ 7' 1" center, averaged a record 50.4 points per game in the 1961–62 season, during which NBA owners limited the number of African-American players to just a few per team.

That season the 25-year-old Chamberlain moved in his own orbit. He drove a white Cadillac convertible, lived in a chic apartment on Manhattan’s Central Park West and commuted to home games in Philadelphia. He co-owned a nightclub in Harlem, Big Wilt’s Smalls Paradise, where he socialized with entertainers such as Cannonball Adderley, James Brown, Redd Foxx and Etta James. His was a lush life with a jazz sound track; he moved through his club as if he owned all of New York City. When a beautiful woman caught his eye he sent an emissary to quietly let her know of his interest. During a game in Philadelphia that season he whispered to a Warriors official at the scorer’s table, “The blonde sitting underneath the basket. Get her number for me.”

• SI LONGFORM: From writer to owner: My saga with the Frost Heaves

In his email Levi, a printmaker and digital artist in San Francisco, said he’d just read my book and was seeking my advice—and help. Ten years earlier, he wrote, “I discovered that Wilt is my biological father.”

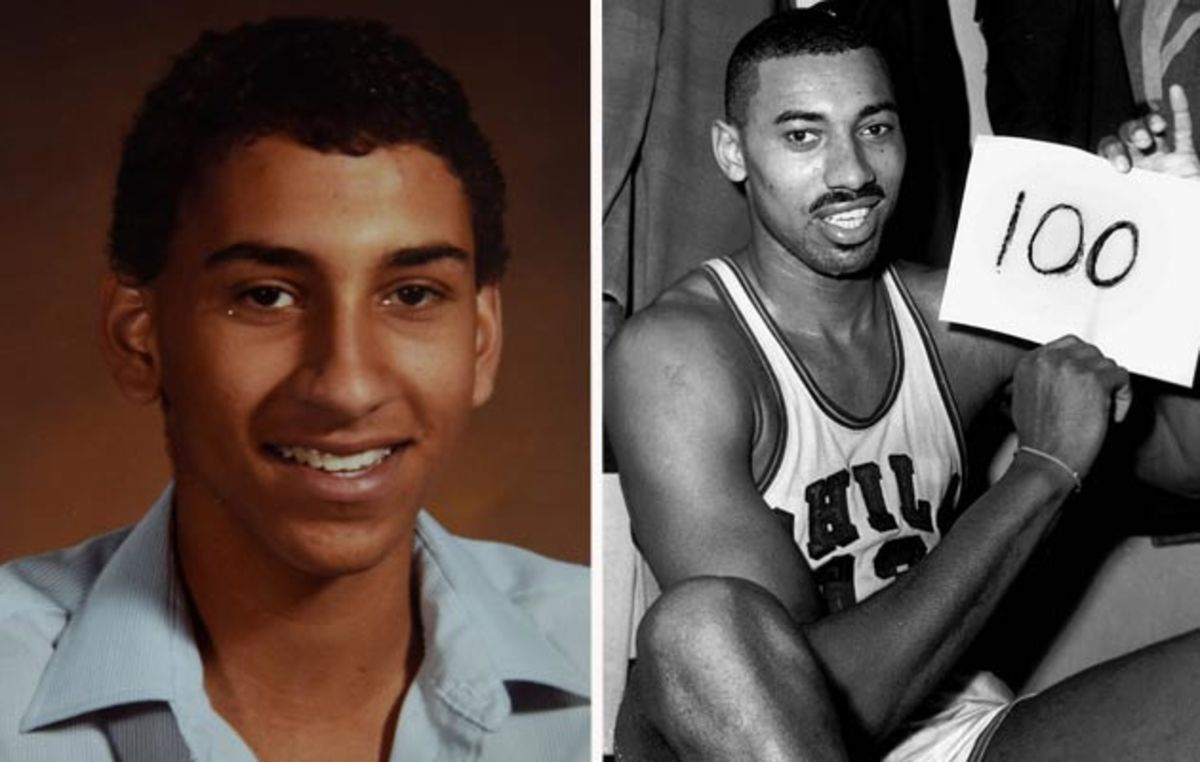

I was skeptical. Legion are those who have reached for fame and fortune by claiming to be the child of a prominent figure. But Levi came to me with more than a story. He had documentation. He showed the “non-identifying” papers from his 1965 adoption, which did not name his biological parents but described them in compelling detail. He sent high school photos of himself, placing them alongside the famous photo of Chamberlain after his 100-point game. The resemblance of the 25-year-old Wilt to the 16-year-old Aaron was striking: the same almond-shaped eyes, arching eyebrows, facial bone structure, even smiles.

In his 1991 memoir, A View from Above, Chamberlain famously boasted of having slept with 20,000 women. The claim reduced him to such a caricature the last eight years of his life that even he made light of the number. A former lover quoted him as saying, “What’s a zero among friends?”

But until the day he died, at 63, from a heart attack at his Bel-Air mansion in October 1999, Chamberlain made it clear there would be no “little Wilties.” He was right in a way. Levi is 6' 5" and weighs 250 pounds.

Chamberlain had what might be called a Goliath complex, a need to prove his greatness in all ways. During my book research, his friends and former teammates told me of how Wilt cheated at cards, boasted that he had driven nonstop from New York City to Los Angeles in 36 hours (“There’s no speed limit in Kansas,” he crowed) and claimed he had killed a mountain lion with his hands.

He played 14 NBA seasons, won two championships, led the league in rebounding 11 times and was the top scorer seven times. He finished with more than 31,000 points, having helped to transform the obscure NBA into a phenomenon. But only two numbers dominated his obituaries: 100, for the legendary night that he produced the only single-triple in NBA history, and 20,000, for the supposed sexual conquests that, he wrote in 1991, “equals out to having sex with 1.2 women a day, every day since I was fifteen years old.”

His editor, Peter Gethers, told me years ago that Chamberlain had said, “You have to understand what it was like in those days. That’s what an athlete did.” Chamberlain, who never married, wrote that once, when he attended a birthday party in San Francisco with 15 women, “I got all but one before the rising of the sun.”

GALLERY: Rare photos of Wilt Chamberlain

Rare Wilt Chamberlain Photos

During his 14-year NBA career, Wilt Chamberlain racked up his share of accolades including scoring an unprecedented 100 points during the Philadelphia Warriors win over the New York Knicks on March 2, 1962. Here are some rarely seen photos of the Big Dipper, from college to the pros and beyond. Wilt was born in Philadelphia in 1936 and was one of nine children raised by William and Olivia Chamberlain a racially-mixed middle-class neighborhood. In fourth grade (when this photo was taken), he developed severe pneumonia that nearly killed him.

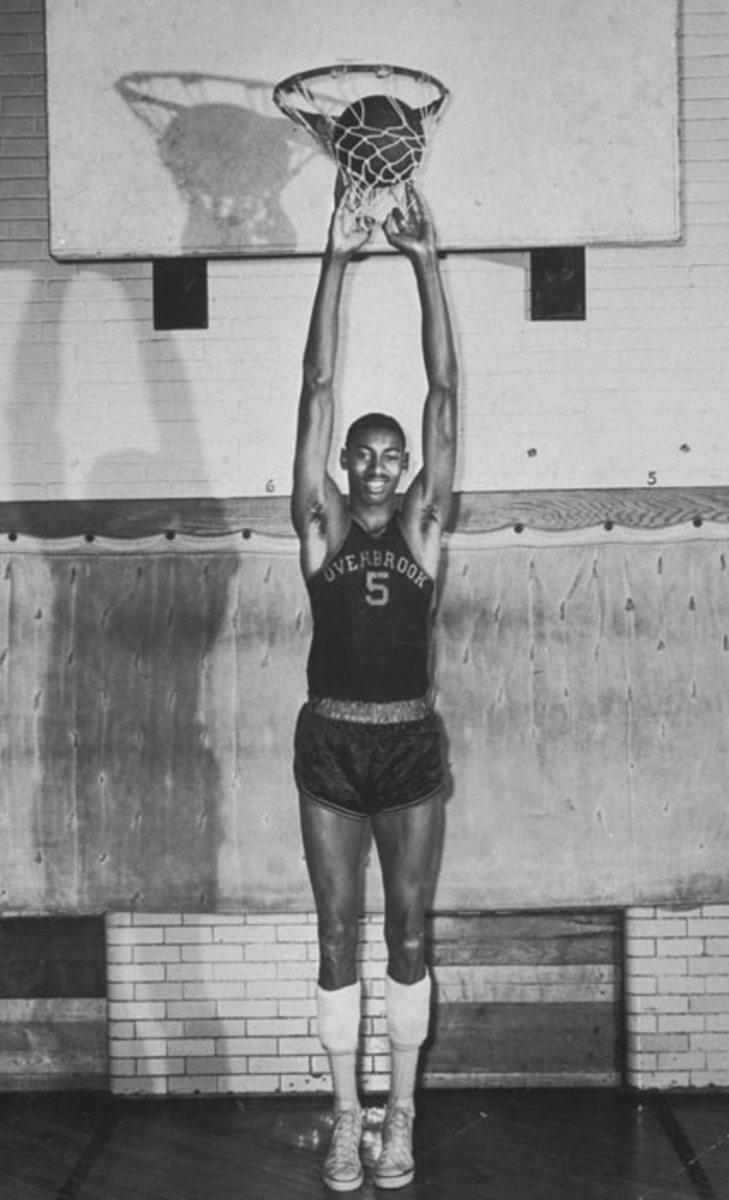

Chamberlain played for his high school basketball team the Overbrook Panthers. He would go on to score 2,252 points during his high school career.

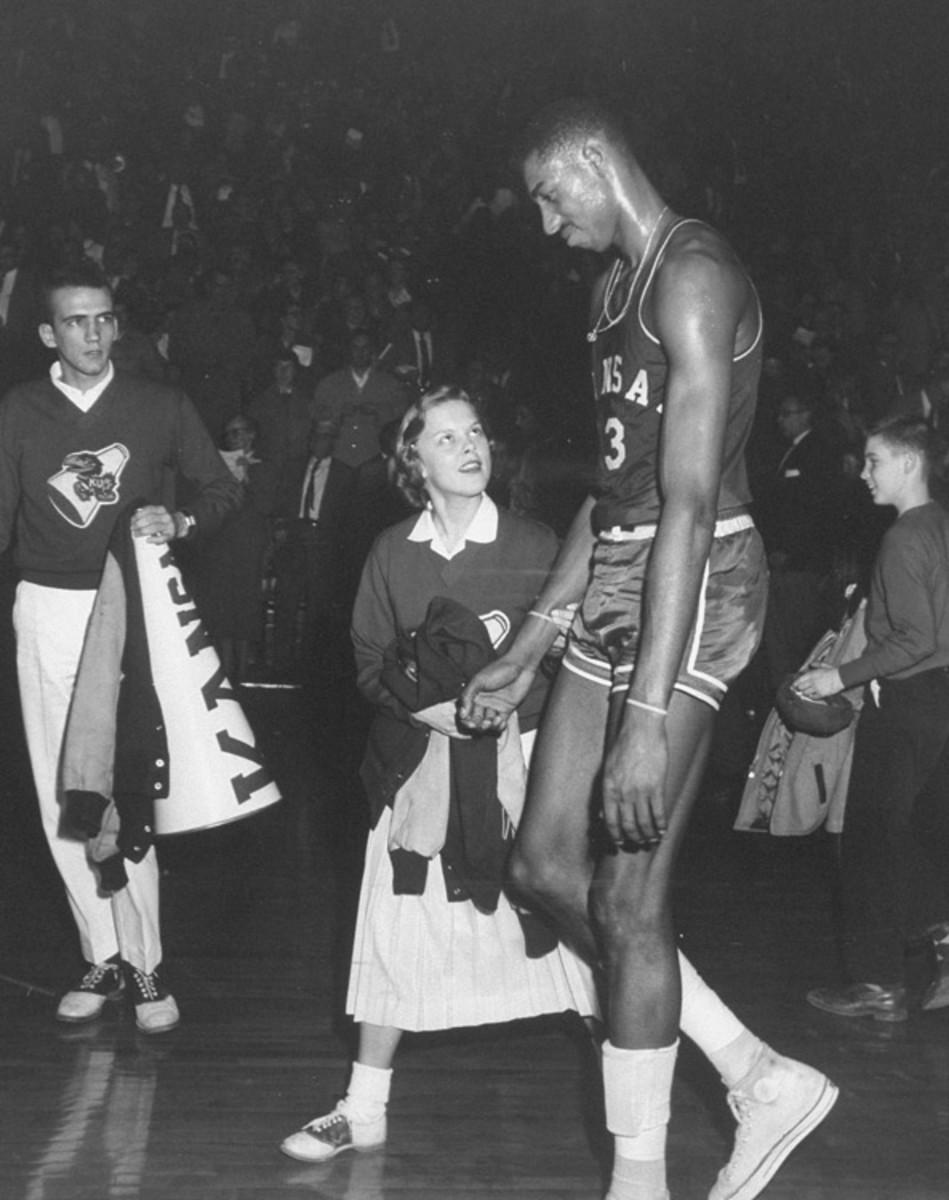

By the end of Chamberlain's high school basketball career, more than 200 colleges were eyeing him. Ultimately the University of Kansas and coach Phog Allen won him over.

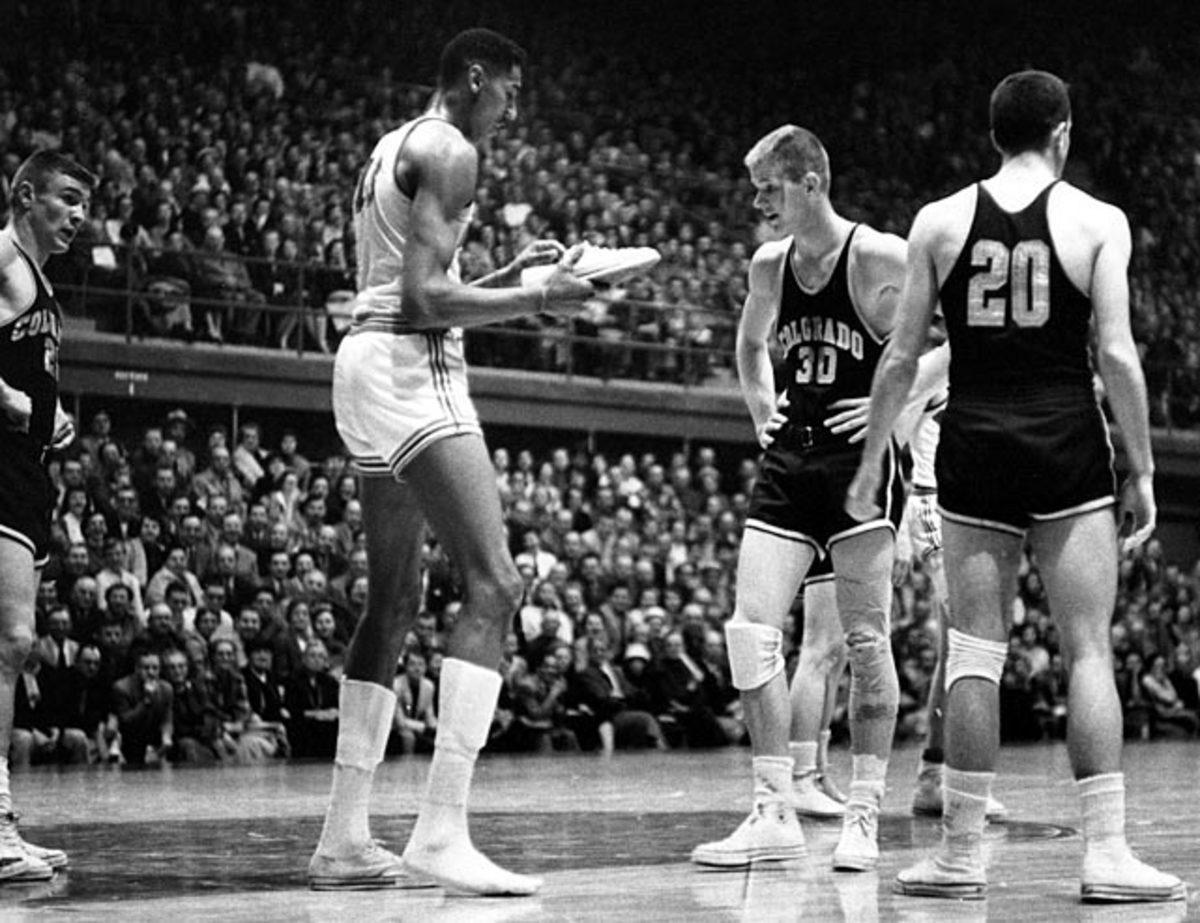

Chamberlain loses his shoe during a 1957 game against Colorado. During his college career he averaged over thirty points per game and was twice selected to All-American teams.

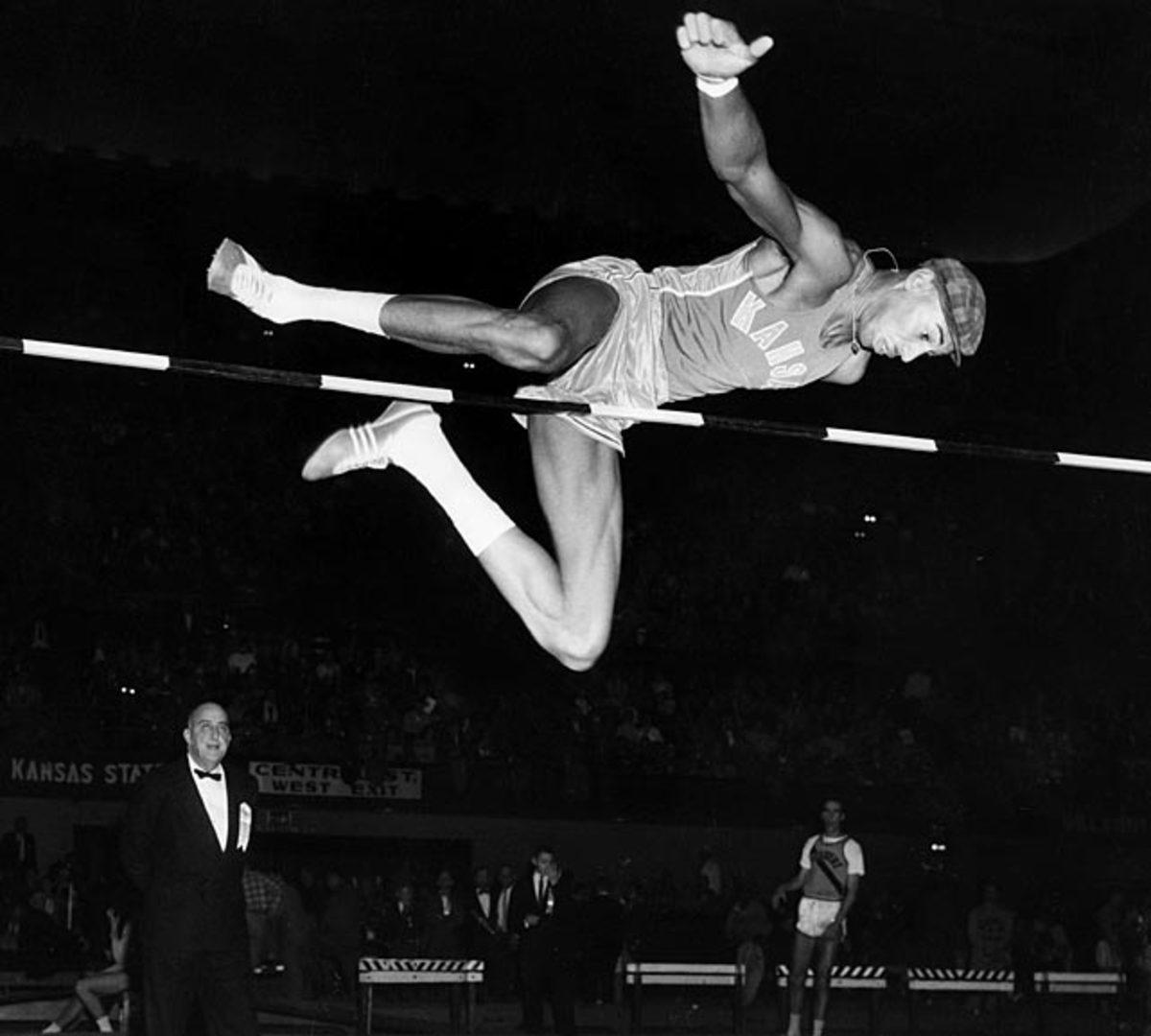

Chamberlain was also a member of the Track and Field team while at Kansas. He ran the 100-yard dash in 10.9 seconds, shot-putted 56 feet and won the high jump in the Big Eight track and field championships three straight years.

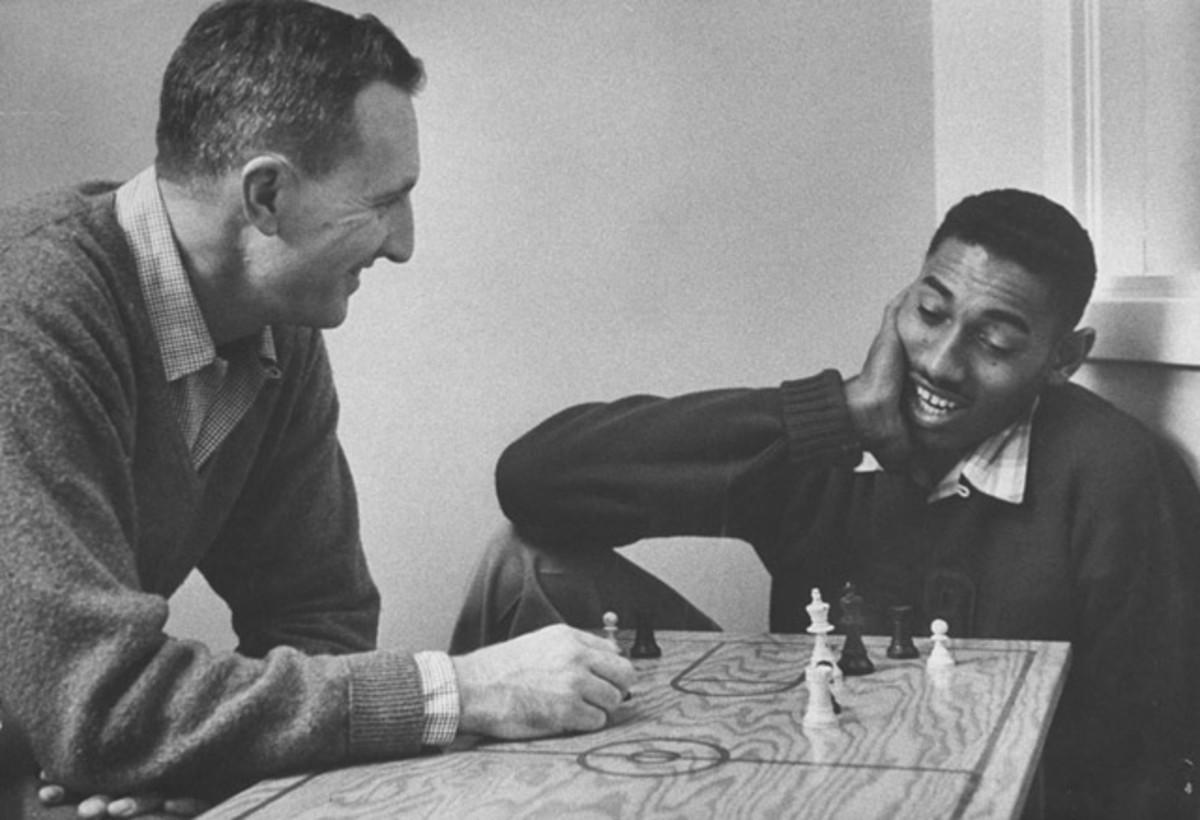

In his two seasons playing for the Jayhawks, Chamberlain, shown playing chess during his college days, scored an impressive 1,433 points and helped Kansas the title game against North Carolina in 1958.

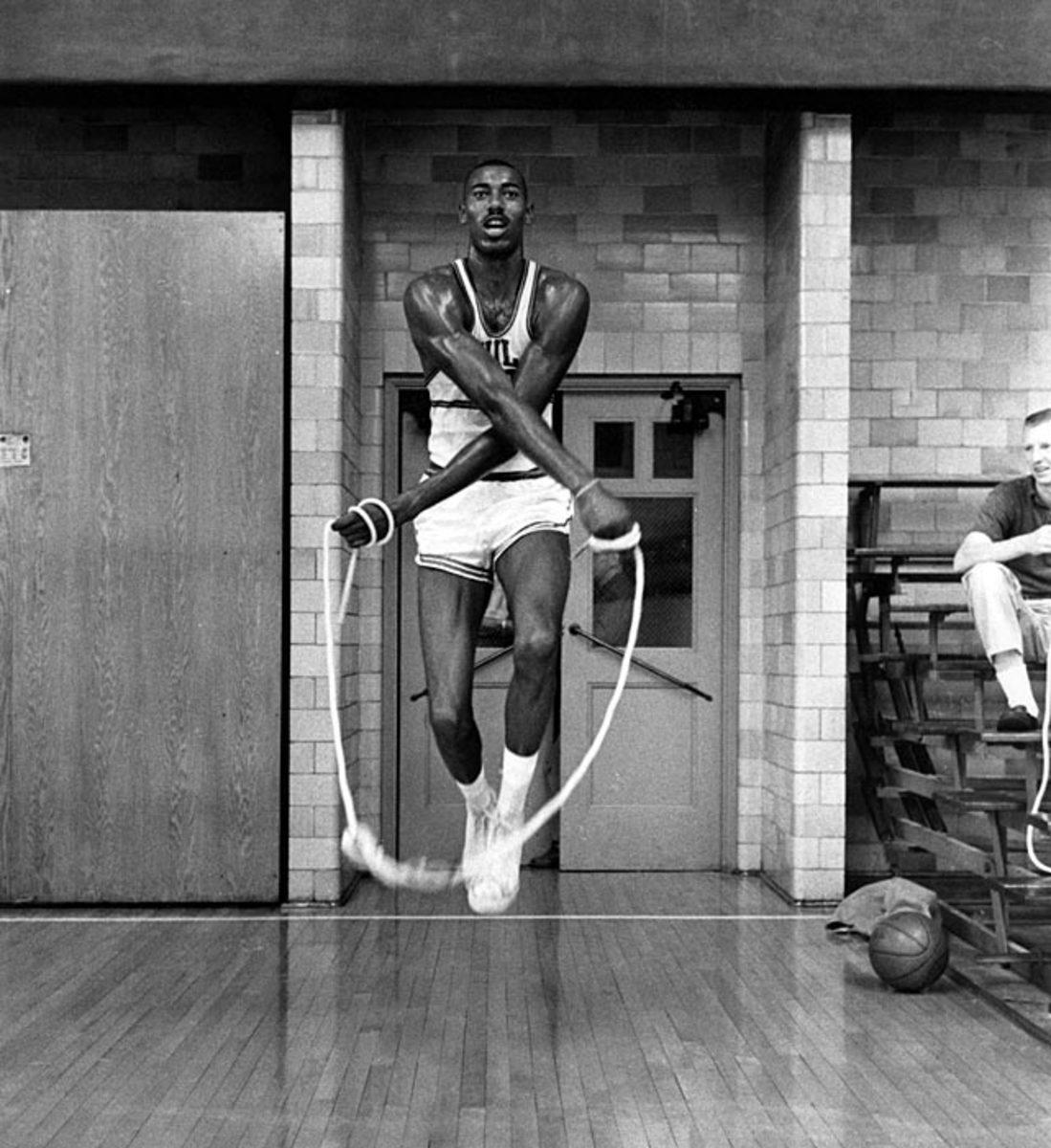

Chamberlain jumps rope before a 1959 practice.

Chamberlain is greeted by Philadelphia Warriors teammates and fans after pouring in a NBA record 100 points in a 169-147 victory over the Knicks.

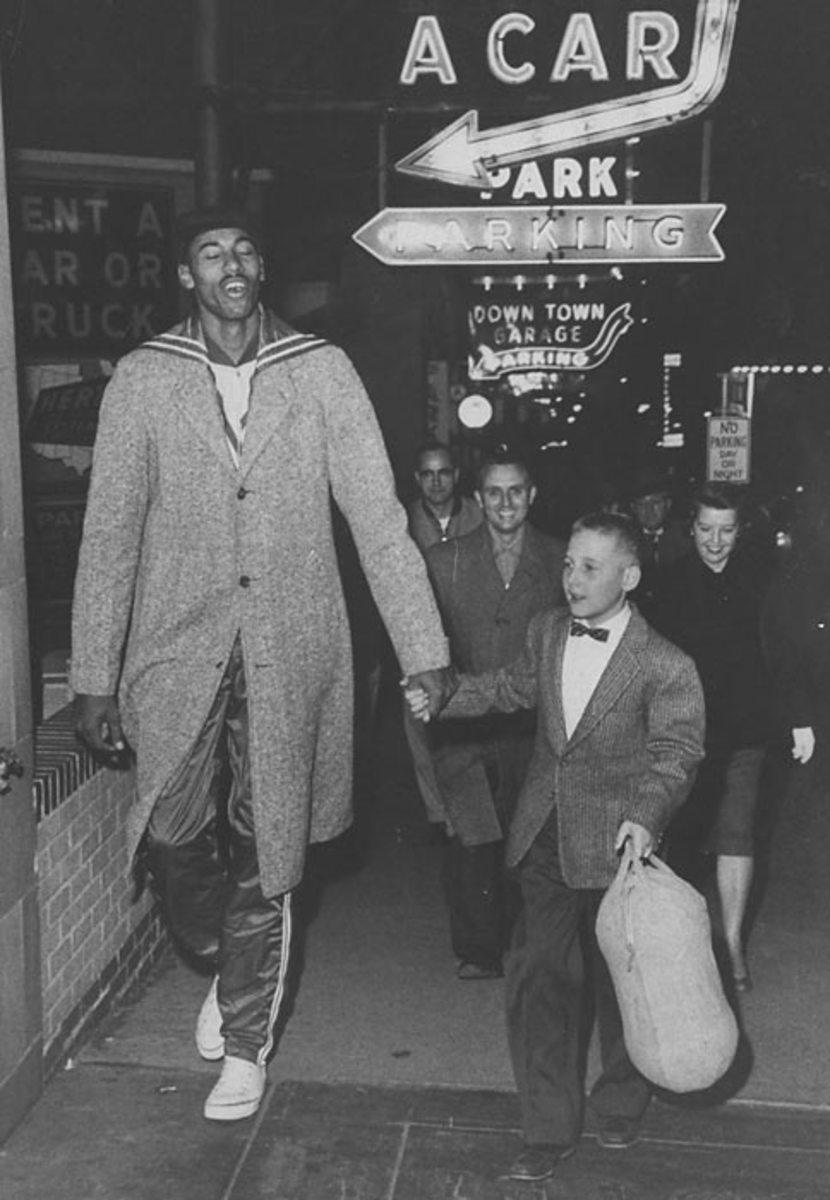

Having hit 6 feet when he was 10 years old, Chamberlain was treated like a star in his hometown of Philadelphia. In 1955, he took his height and fame to Kansas.

Barely able to fit his 7-foot-1 frame under the desk, Chamberlain is seen here sitting in class at the University of Kansas in 1957. Chamberlain would play for the Jayhawks and also become a member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity while at Kansas.

During his junior year at Kansas, Chamberlain grew frustrated as opponents often triple- or quadruple-teamed him. Though he averaged 30.1 points that season and was again named an All-American, the Jayhawks lost to North Carolina in the national championship game.

Chamberlain's first foray into the pros brought him to the then-Philadelphia Warriors in 1959. With the Warriors, the Philadelphia native became the first player to break the 2,000-rebound barrier in a single season.

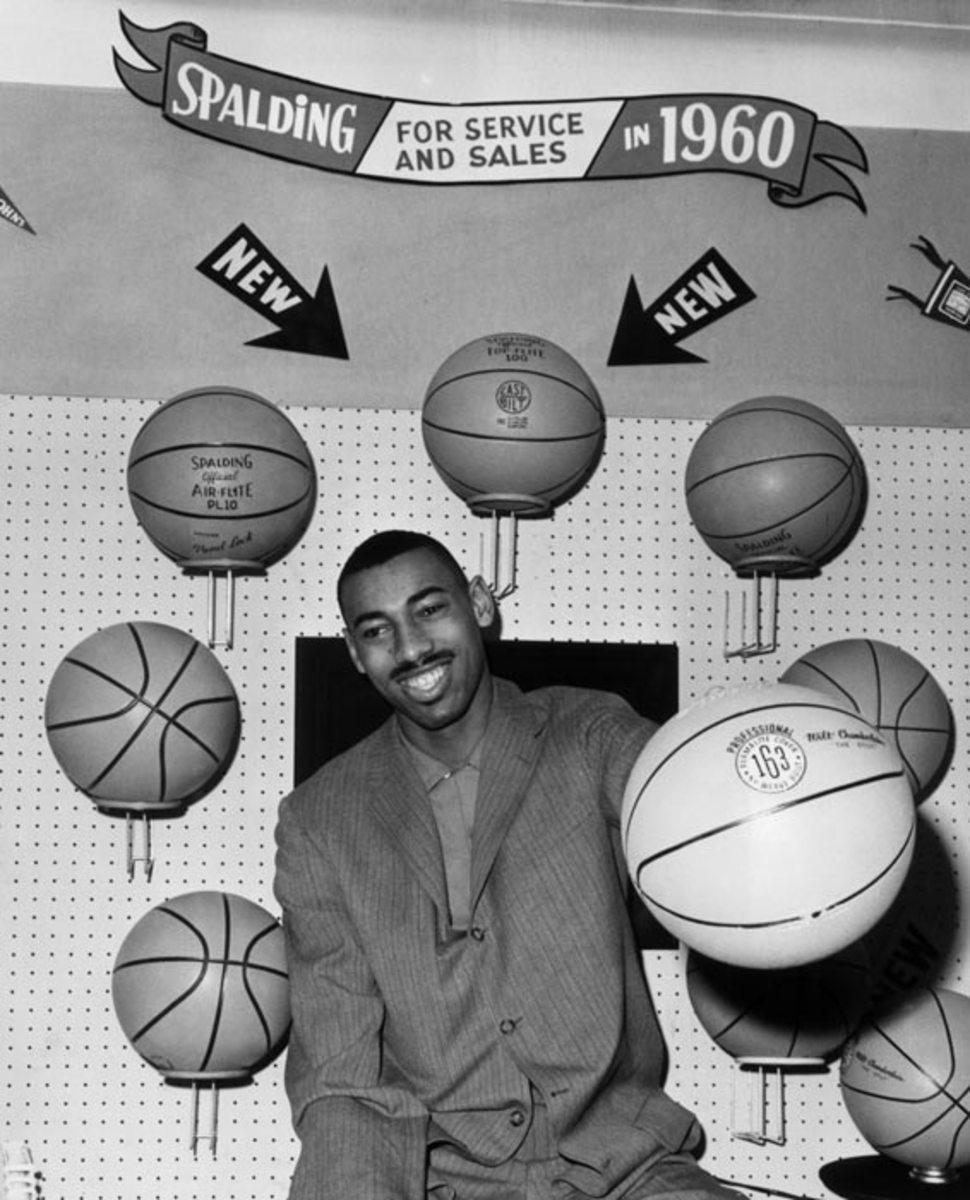

Chamberlain holds a Spalding basketball during the opening of a Sporting Goods store in 1960.

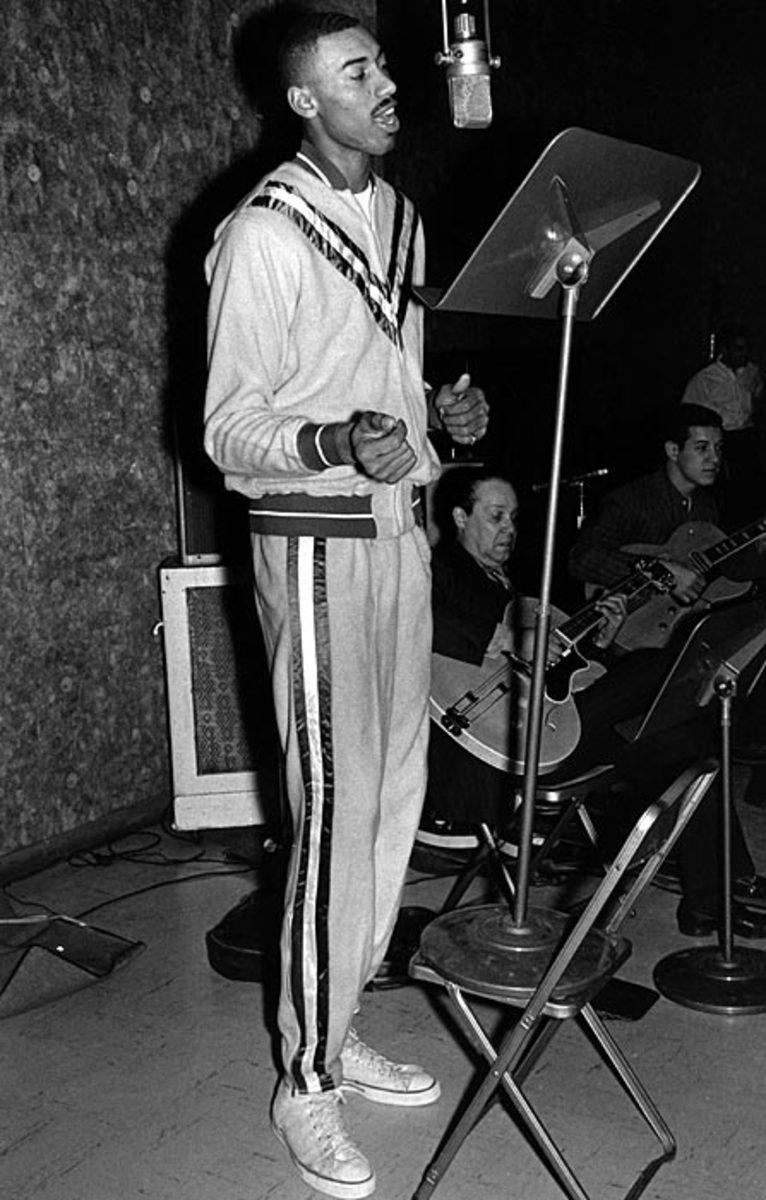

Chamberlain, who hosted a college radio show called "Flippin' with the Dipper," works on his vocal skills. Click here to sing him singing By the River.

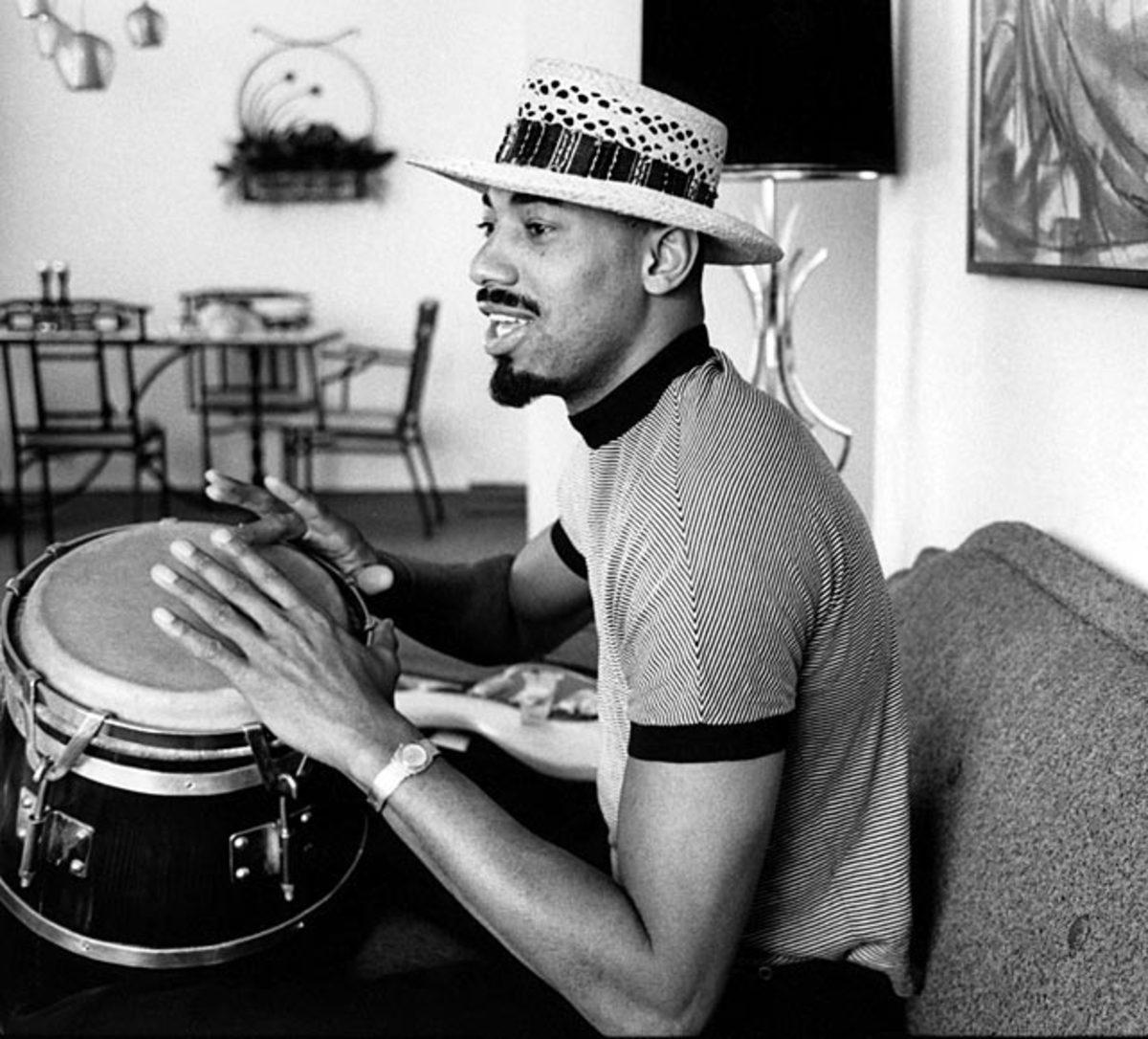

Chamberlain practices his percussion skills in his New York city apartment.

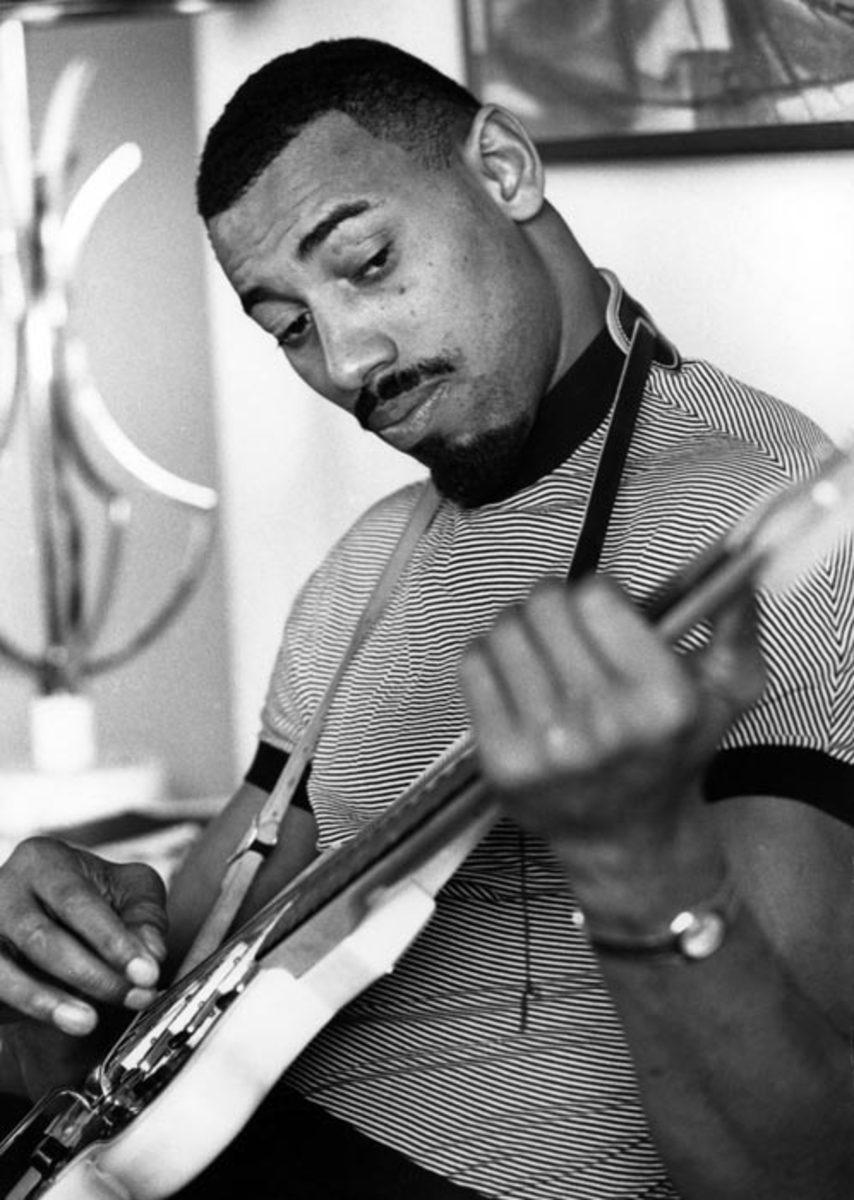

Drums aren't the only instrument Chamberlain can play. In this photo, Wilt works on his guitar playing.

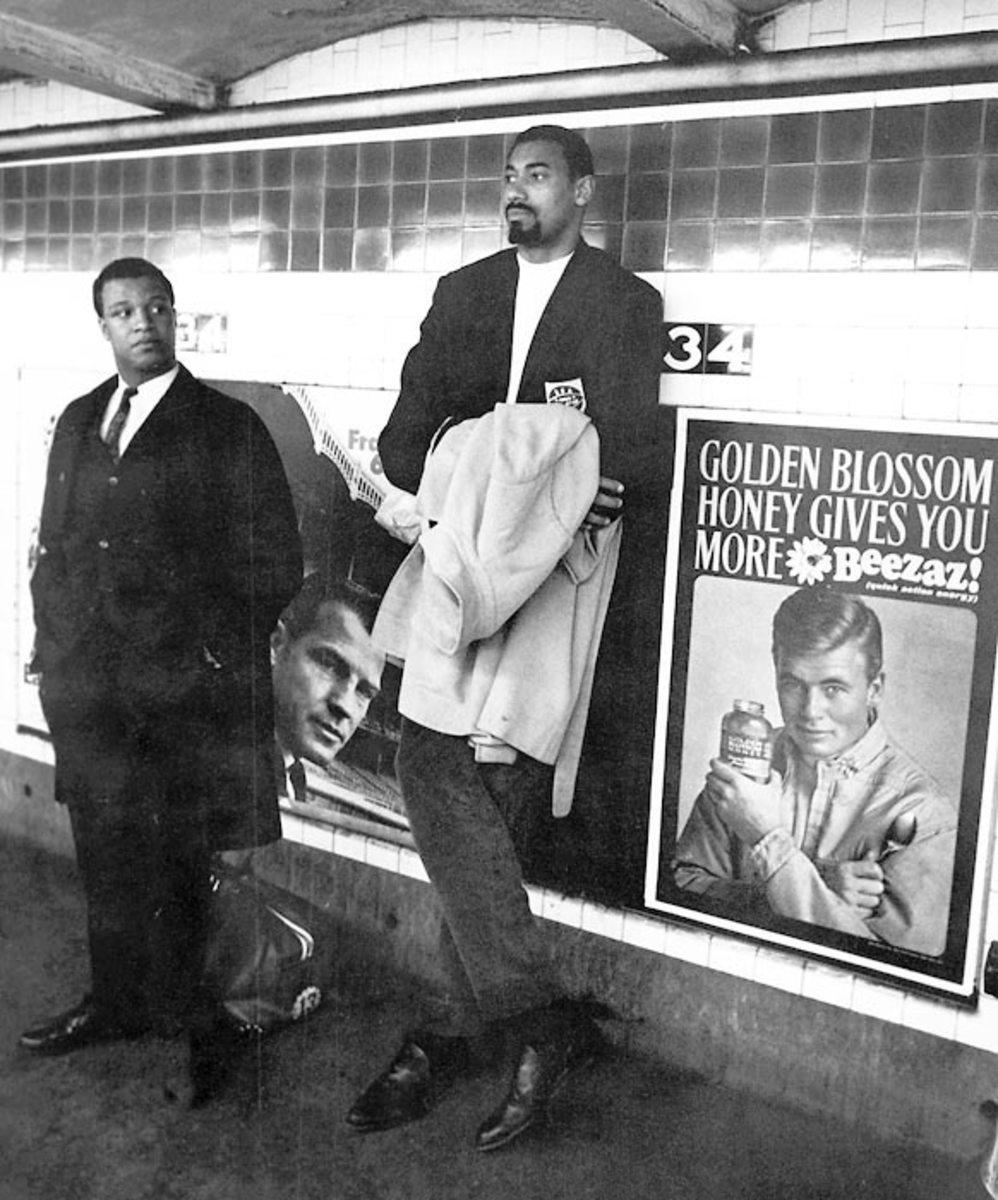

Chamberlain was as known for his massive stature as he was for his smooth moves on the court. Nicknamed "Wilt the Stilt," "The Big Dipper" and "Goliath." Imagine seeing him in a New York City subway station.

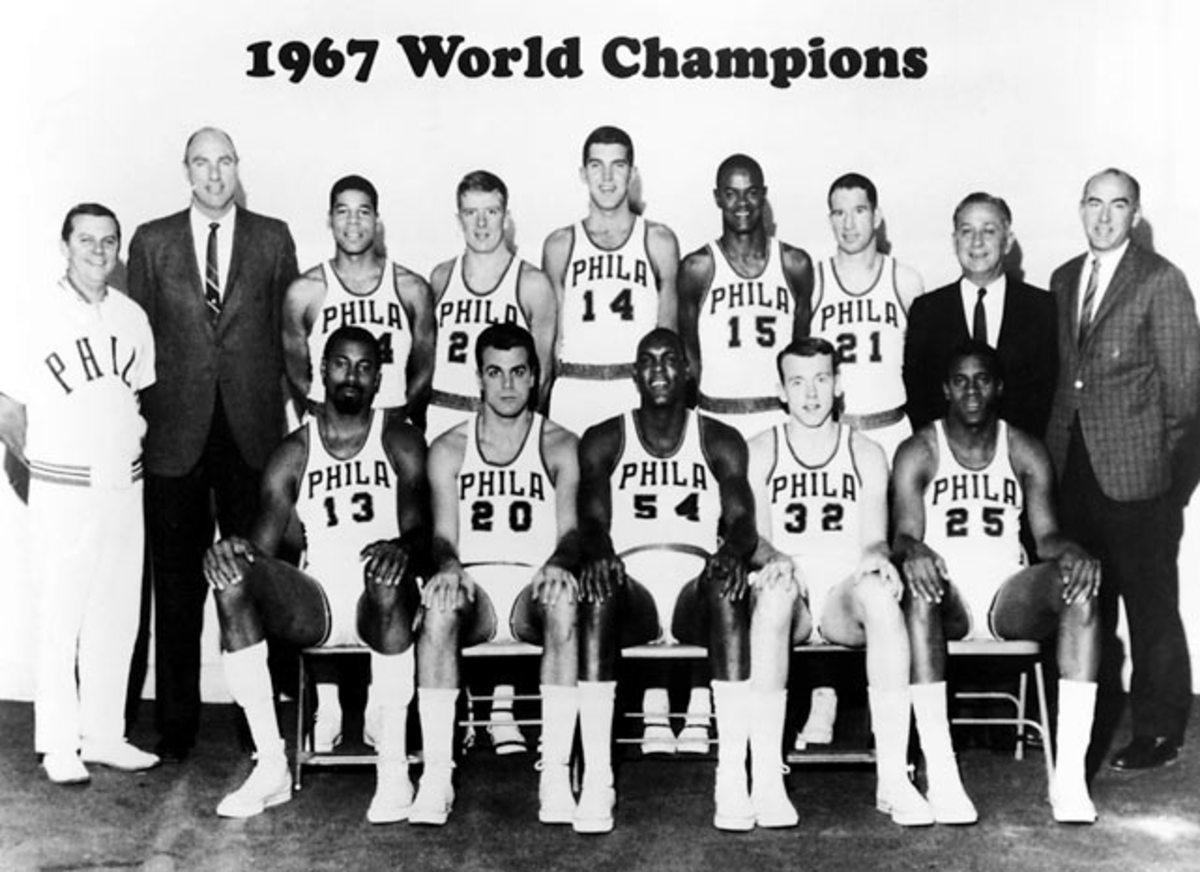

Before his five-season stint with the Lakers, Chamberlain called Philadelphia home. "The Stilt" played for the Sixers alongside Hall-of-Famer Hal Greer and Chet Walker. Chamberlain would cap off his Sixers stint with a record 21 assists for the team.

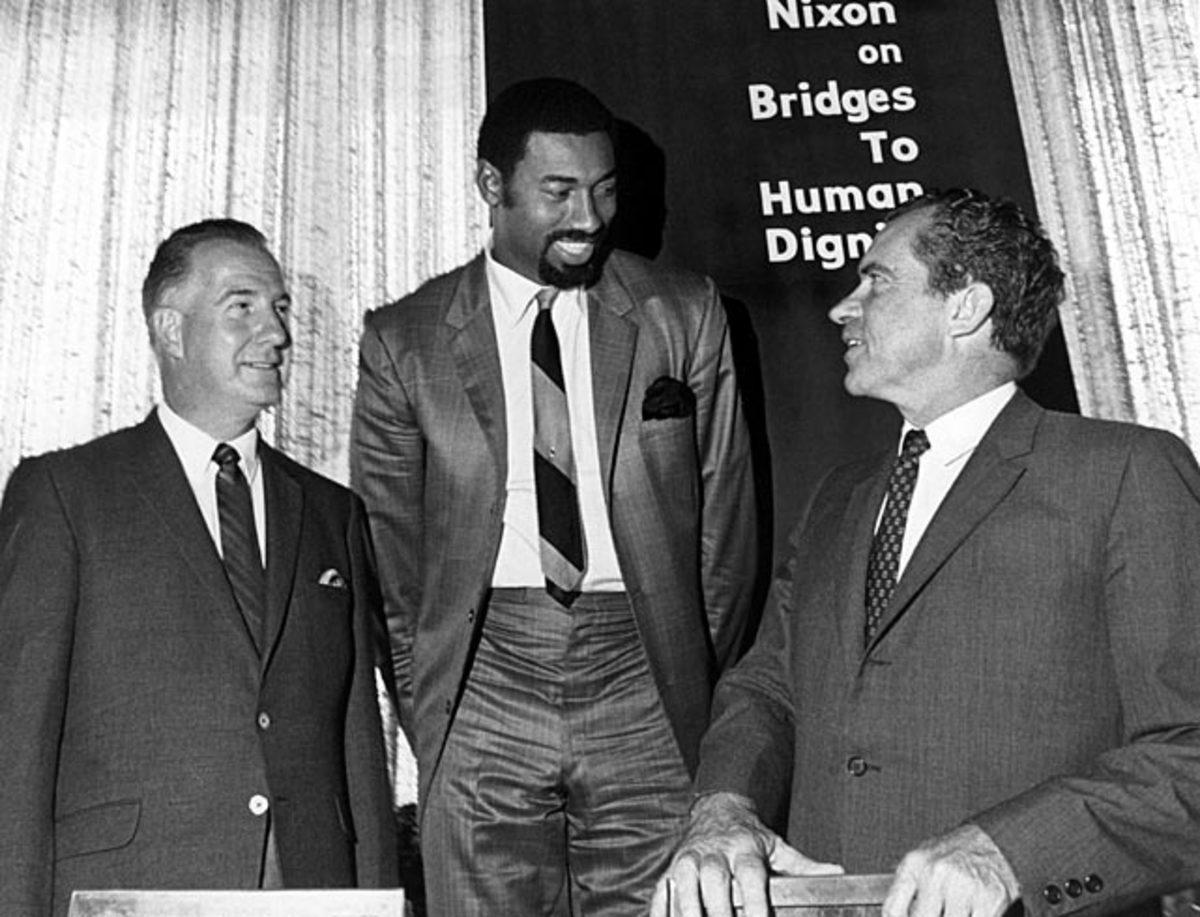

Chamberlain poses with United States president Richard Nixon with and Maryland governor Spiro T. Agnew during an event in Mission Bay, Calif. Chamberlain was a supporter of Nixon and helped tout the president's ideas on "black capitalism."

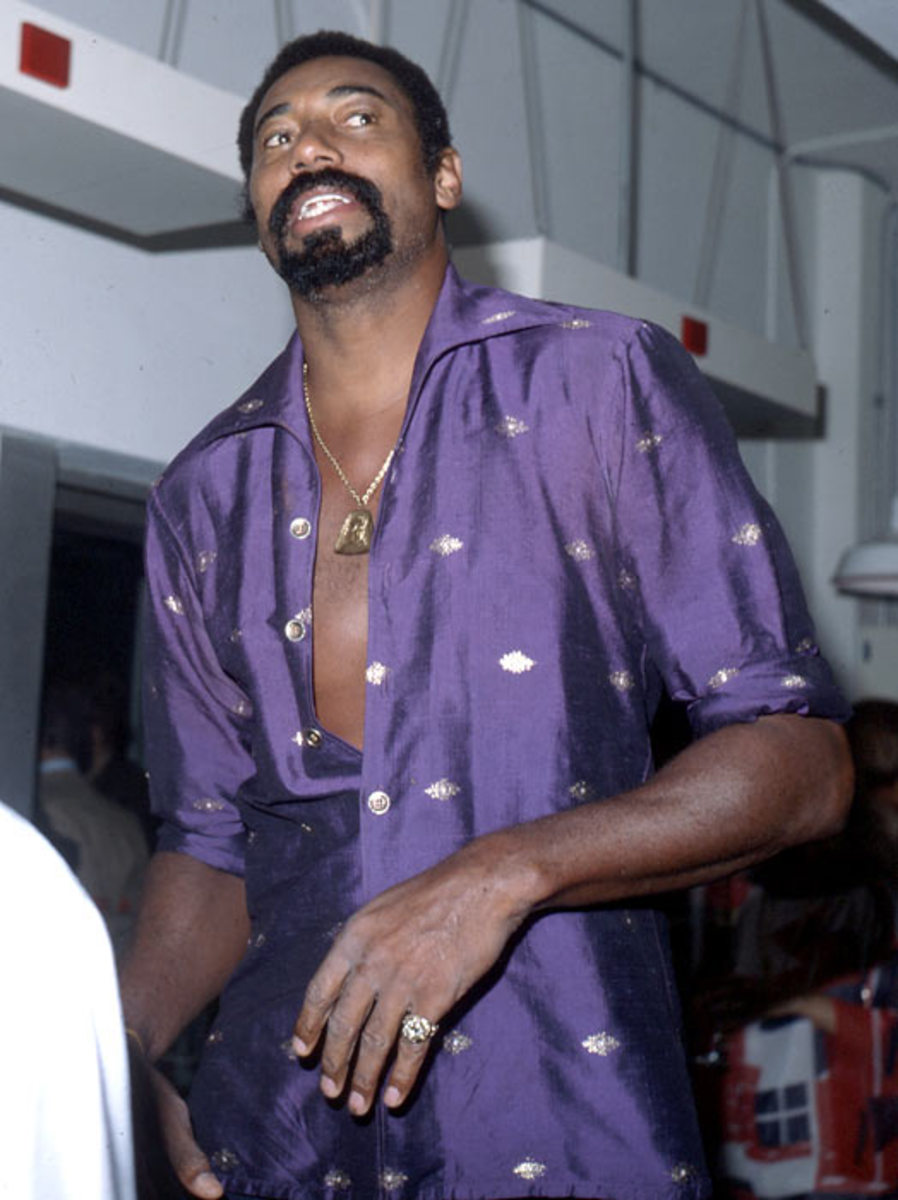

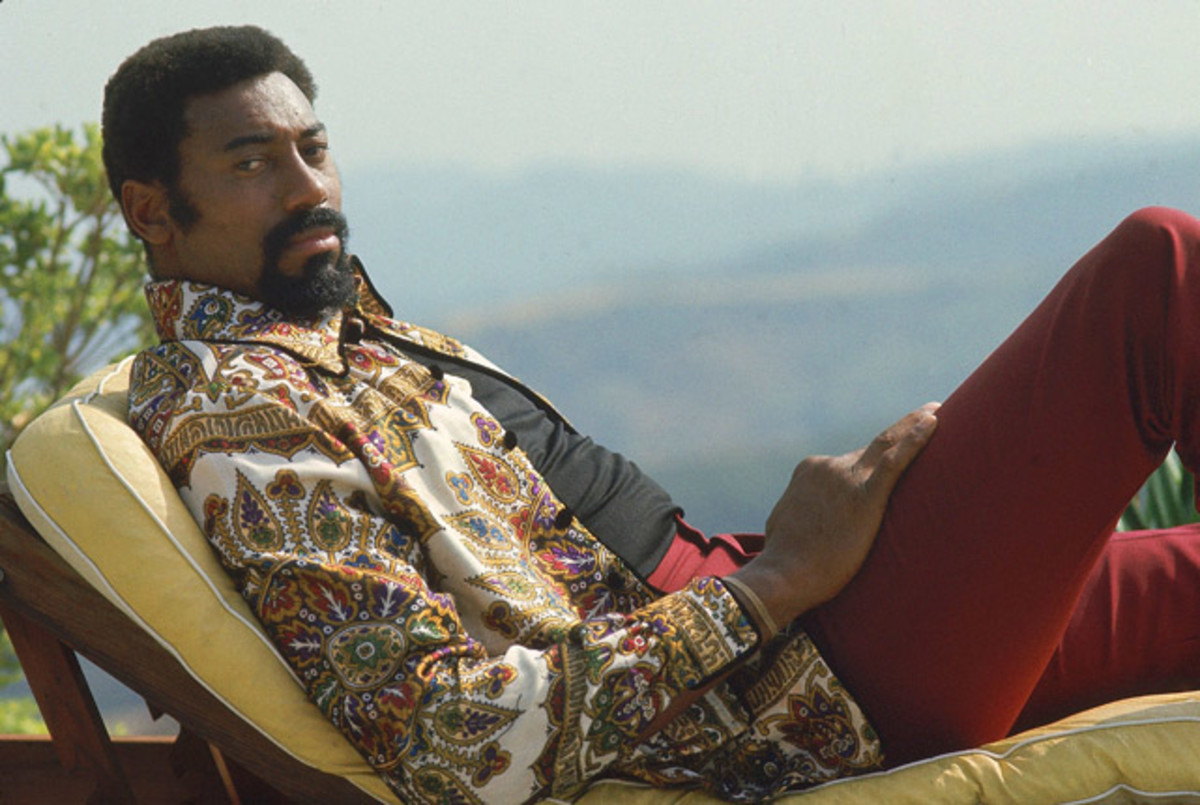

Playing alongside multiple future Hall of Famers in Los Angeles, Wilt always managed to find someway to stand out -- if not by his on-court accolades, by his off-the-court attire.

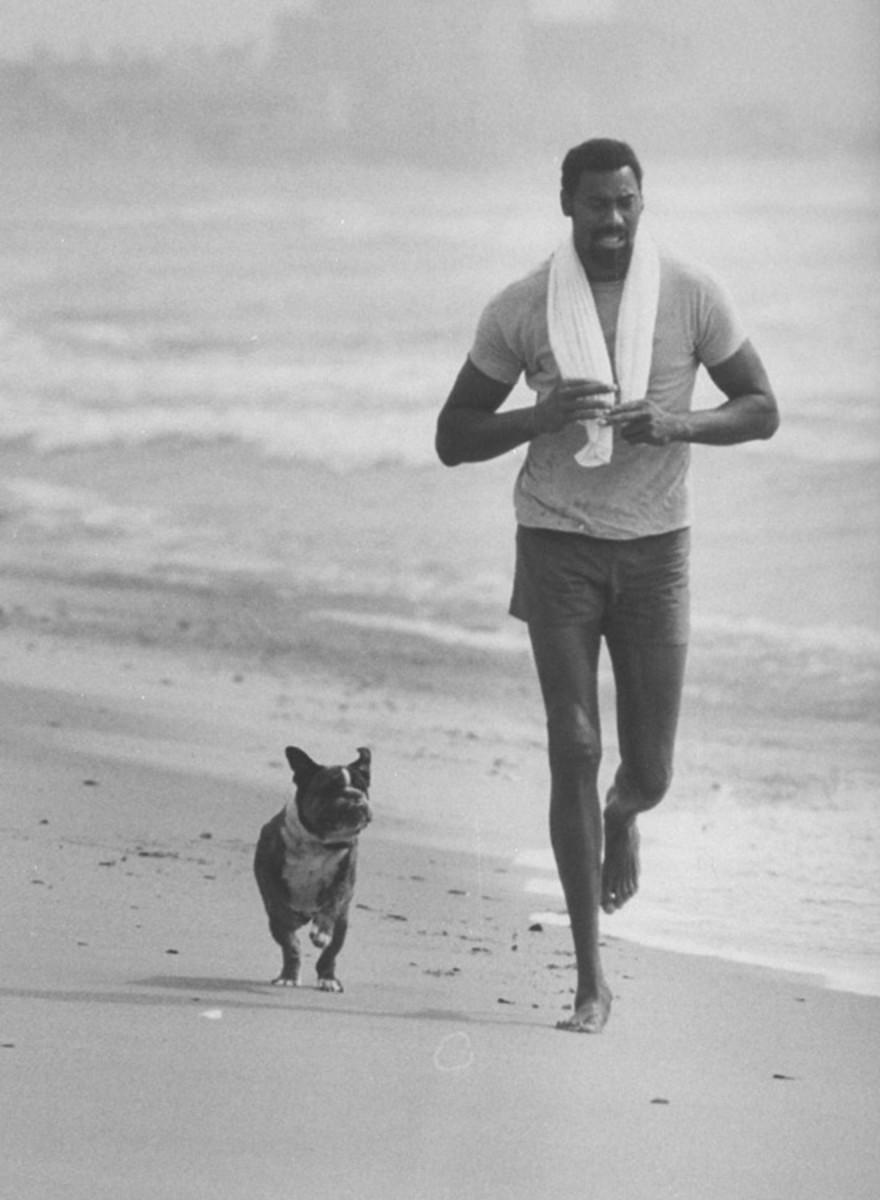

Wilt and his dog take a jog along the beach in California. Keeping up with Chamberlain's long strides couldn't have been easy for a dog.

If he wasn't grabbing a rebound or tipping in a bucket, Wilt was usually lounging around ... in this pose.

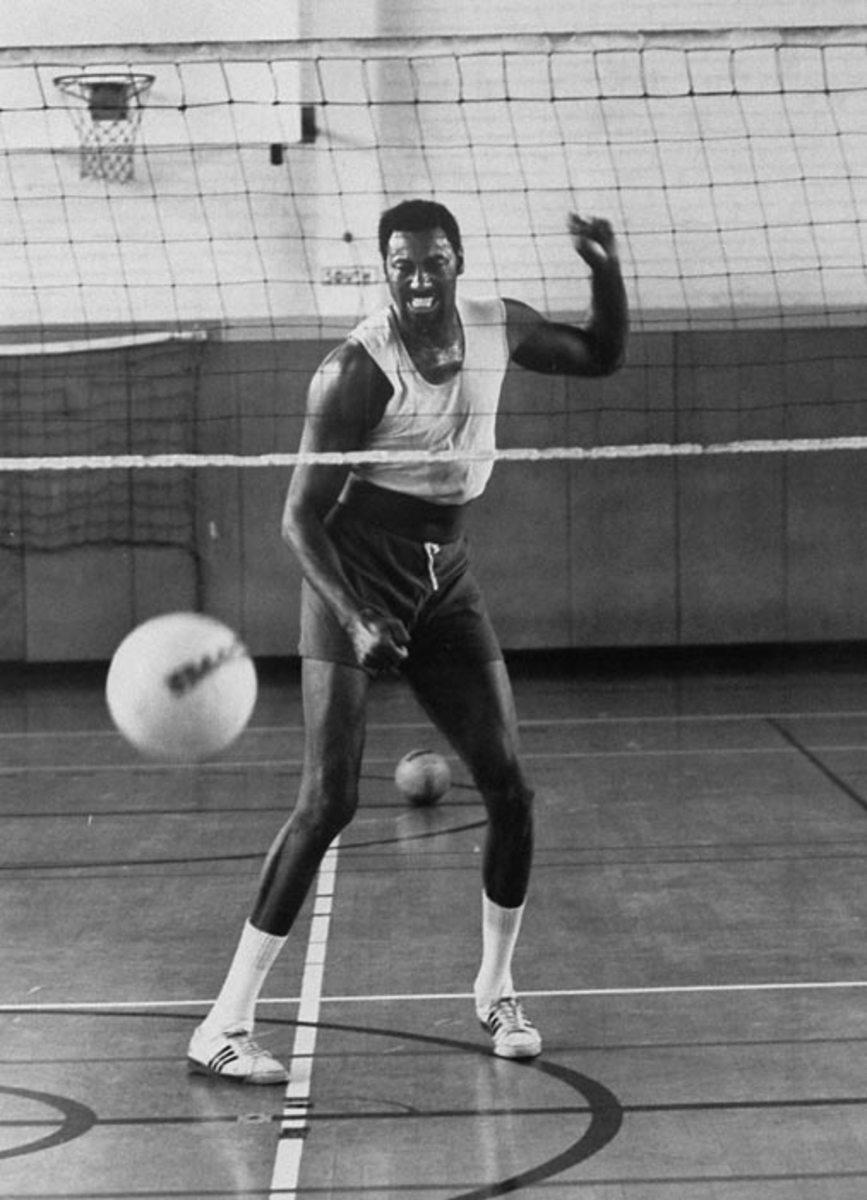

In addition to basketball, Chamberlain had a love for volleyball. He became president of the International Volleyball Association and was later named to the sport's hall of fame.

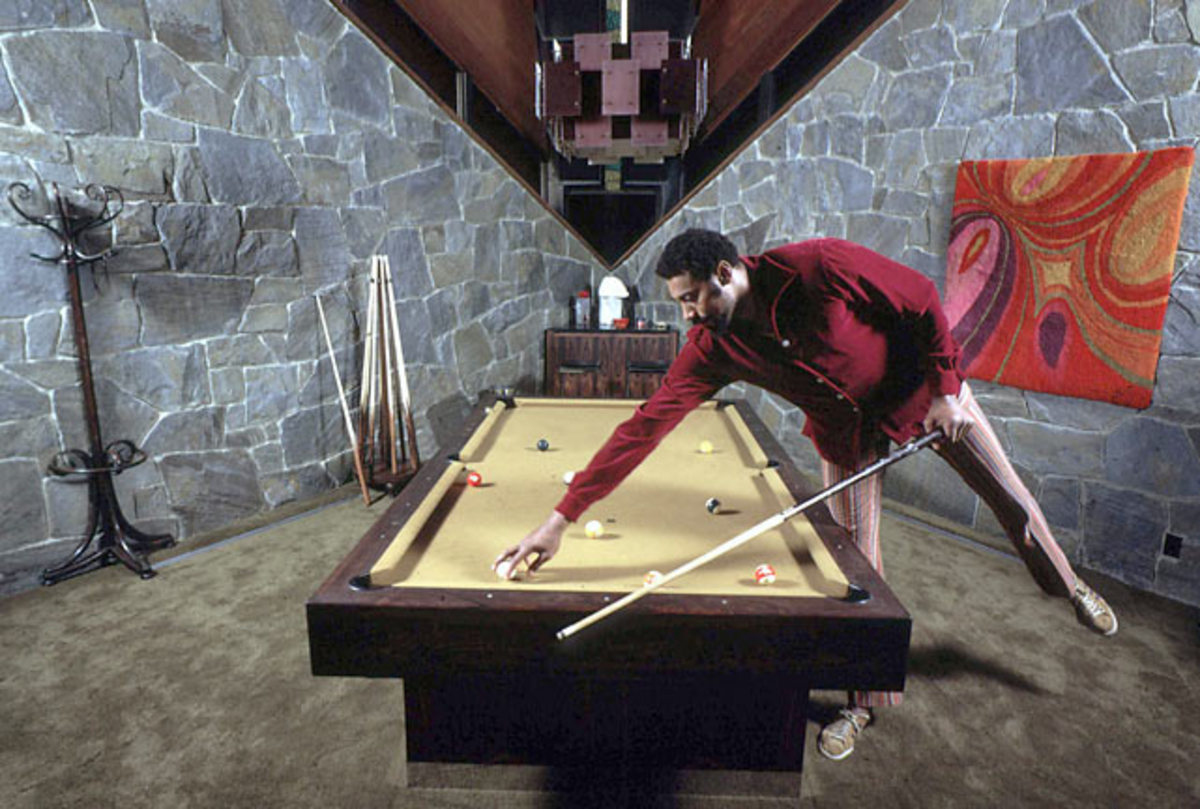

Seen here playing pool, Chamberlain named his sprawling Bel-Air home Ursa Major as an ode to the stars that make up the Big Dipper.

After his stint in the ABA with the San Diego Conquistadors, Wilt found success in the real estate and movie businesses, allowing him to continue his lavish lifestyle long after his playing days.

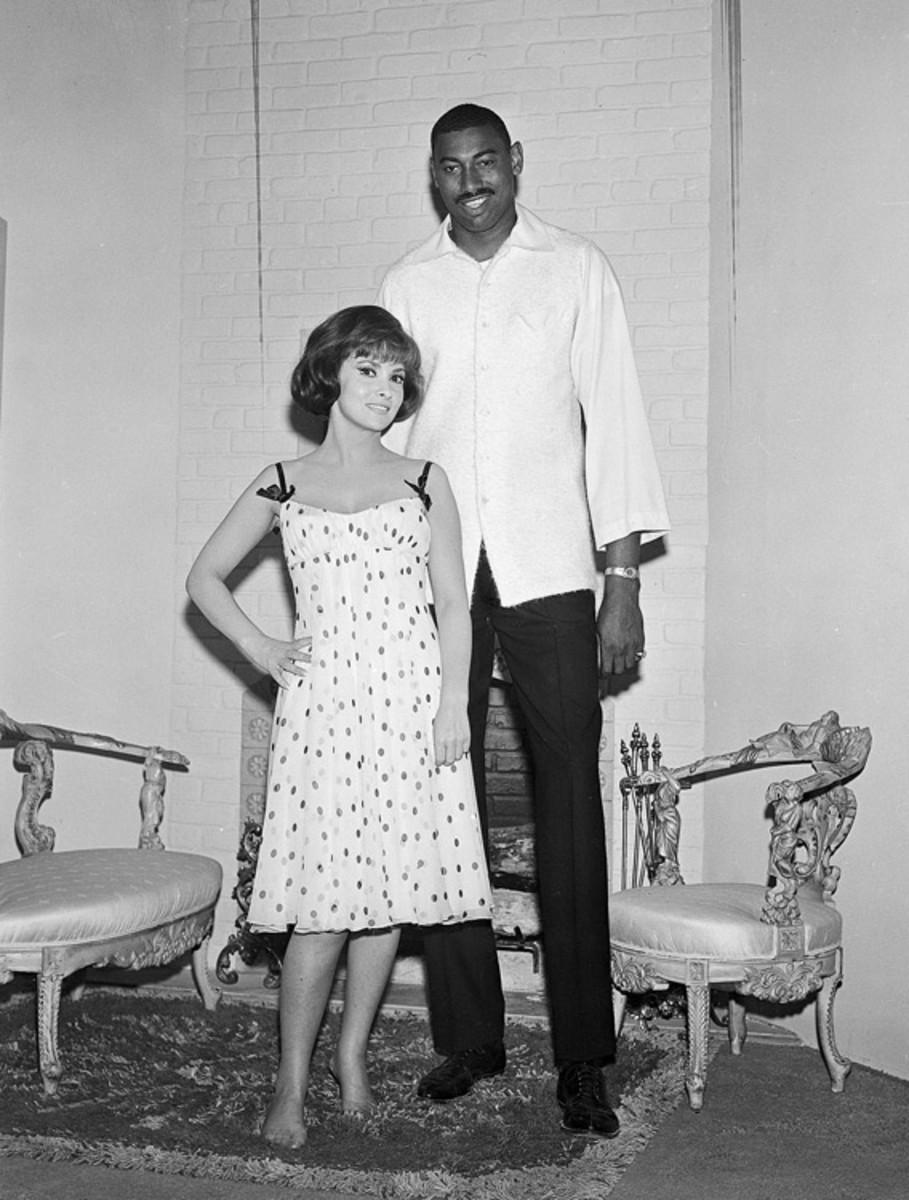

Chamberlain towers above actress Gina Lollobrigida on the set of "Strange Bedfellows."

While in retirement, Chamberlain wrote several books and even launched an acting career. He starred in the 1984 movie "Conan the Destroyer" opposite Arnold Schwarzenegger.

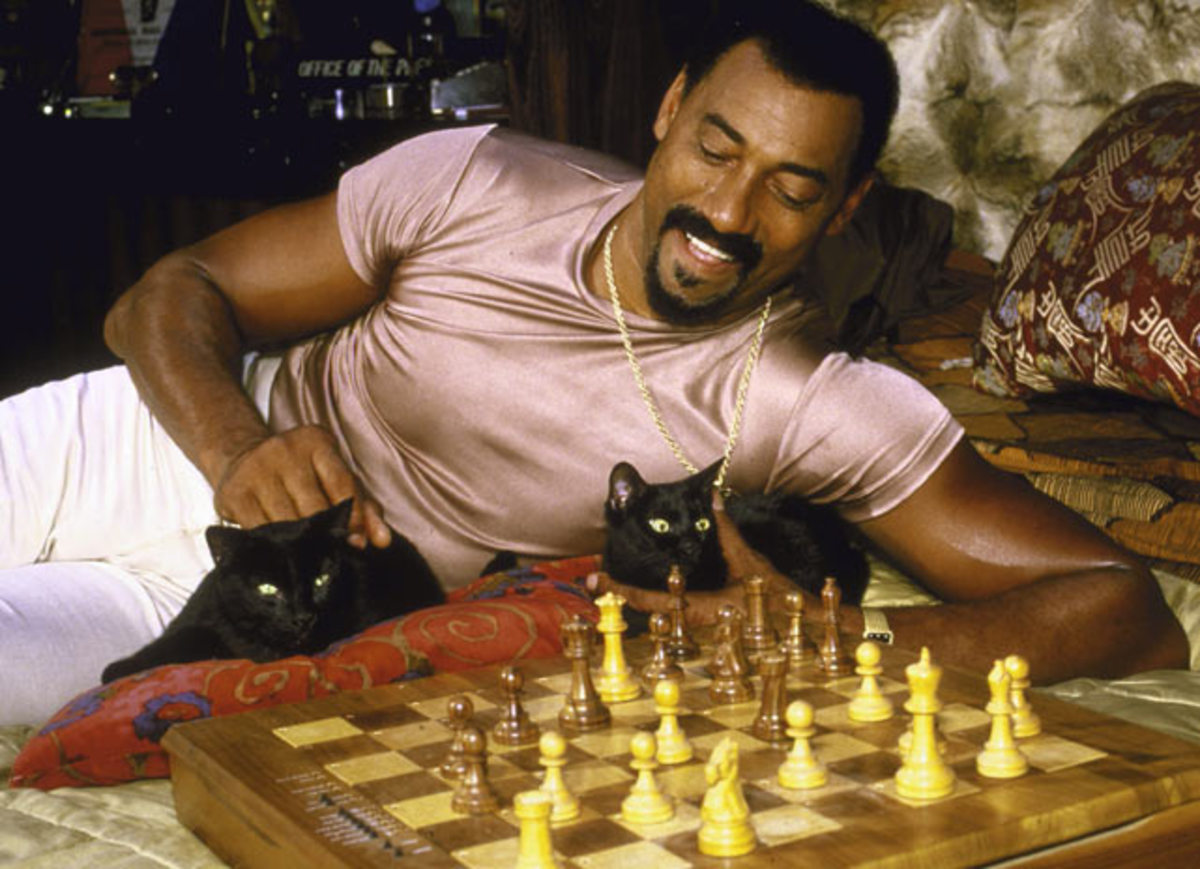

Among one of his many post-basketball endeavors: posing for a 1986 Purina Cat Chow celebrity calendar.

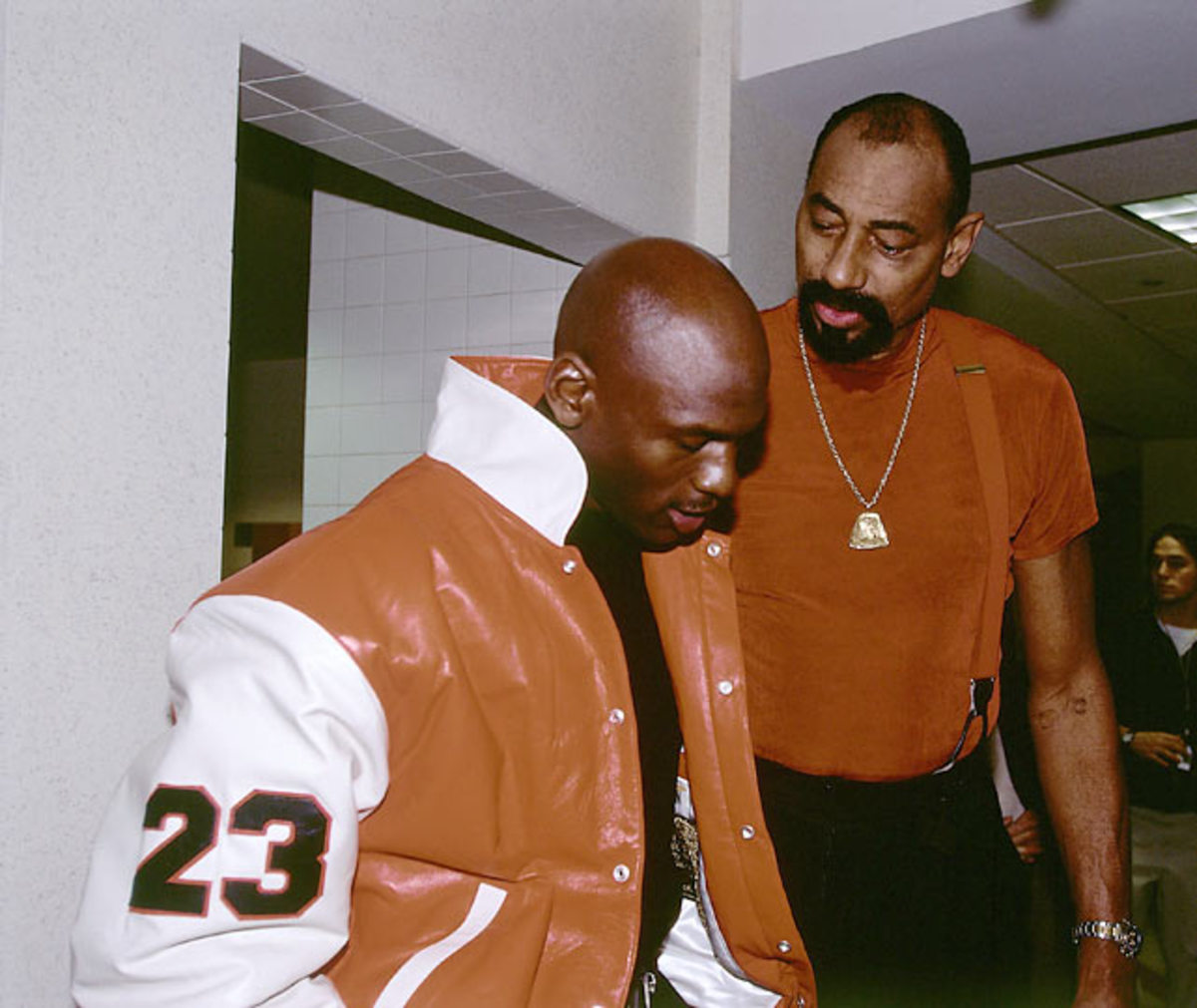

Chamberlain and Bulls legend Michael Jordan participate in the NBA at 50 celebration in 1997. They are the only players to amass 3,000 points in a single season.

His boast was a public relations disaster. He was on a book tour when Magic Johnson announced he was HIV positive. Soon Chamberlain’s endorsements vanished. On Saturday Night Live in 1991 rapper MC Hammer, portraying Wilt in a sketch, produced a woman’s photo and said, “Tonight I remember Cheryl, No. 13,906, but in my heart she was No. 2,078.”

In his email to me, Levi said that after he finally identified a British woman as his biological mother, she told him that he was conceived in a one-night stand with Chamberlain in San Francisco in 1964. She said she had kept his birth a secret from her own family and had struggled ever since with guilt over his birth and adoption. Levi added that in 2010 he reached out to two of Chamberlain’s sisters, by letter and by phone, but they spurned him.

Levi said he did not want a dime from the Chamberlain family and did not want to sully Wilt’s name. Rather, he wanted to meet members of the black side of his family and learn more about his biological father; to correct the “false history” that Chamberlain had no children; and to find out if Chamberlain had any other children, who would be his half-siblings. Levi said the search occupied nearly his every waking moment. He was ready to go public with his story.

I talked with Levi by phone the day after receiving his email. Then we met for coffee. I’ve interviewed him 10 times, three of them at his two-bedroom apartment in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, where he lives alone. “I am simply an adopted person who has been on a long journey of self-discovery,” he wrote, “and [am] reaching out to people to learn more about where I came from.” His aunt Victoria (Vicki) Levi, a Boston-area psychiatrist, said his essential questions are, “Who does he belong to? Where are you in the world? Who are you? Who claims you as theirs?”

[pagebreak]

His adoptive father, Don, a rabbi’s son and a retired University of Oregon philosophy professor, said, “Aaron has been, I won’t say obsessed, but he’s been preoccupied for some time about this.”

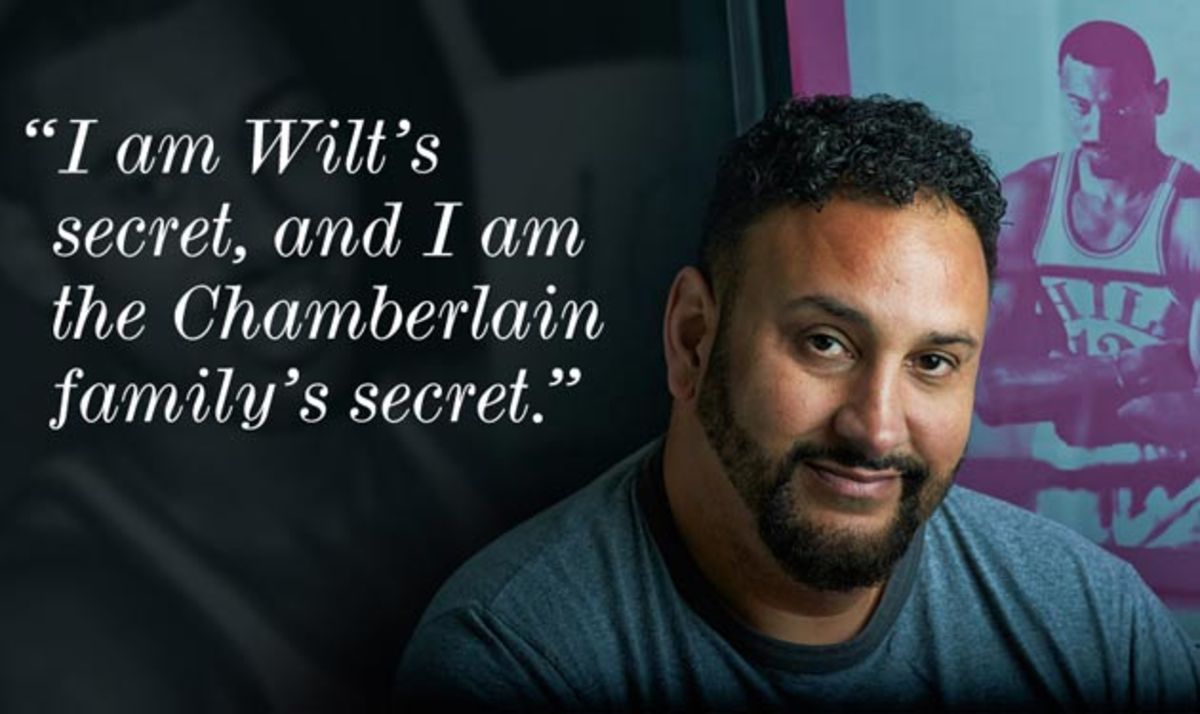

“It’s been a burden on me to feel that I am her secret,” Aaron said of his biological mother, “and I am Wilt’s secret, and I am the Chamberlain family’s secret. That’s been hard for me. . . . I already know what’s going to happen if I don’t do anything. I’m going to have an unfinished journey.”

Levi's living room, on the second floor of a Victorian house, is light and airy, decorated in earth tones. There are books (some about Chamberlain), a long row of DVDs from The Avengers television series, a flat-screen TV and a soft tan couch. French doors open to his bedroom. In a second bedroom a manual four-color printing press is set up.

For the past decade Levi has lived in the city where his story began. He doesn’t look much like Chamberlain now. He is soft around the middle and has a receding hairline. Nor is his movement athletic; he’s more of a lumberer. He’s an engaging conversationalist. His emotional pain seems close to the surface.

Bob Spector, a boyhood friend from Oregon who lives only a few blocks away, shares dinner and a TV movie with Levi once a week and counts him as his closest friend. Nevertheless, Spector said, “Aaron spends a lot of time alone.” Levi is deeply introspective, and when he spoke of his long search for his biological parents, his voice turned somber. “It all comes back to the sadness that Wilt’s not here,” he said. If Chamberlain were alive today, he would be 78. “I guess I’m still reaching out,” Levi said, “because the ultimate person for me to reach out to is just not there.”

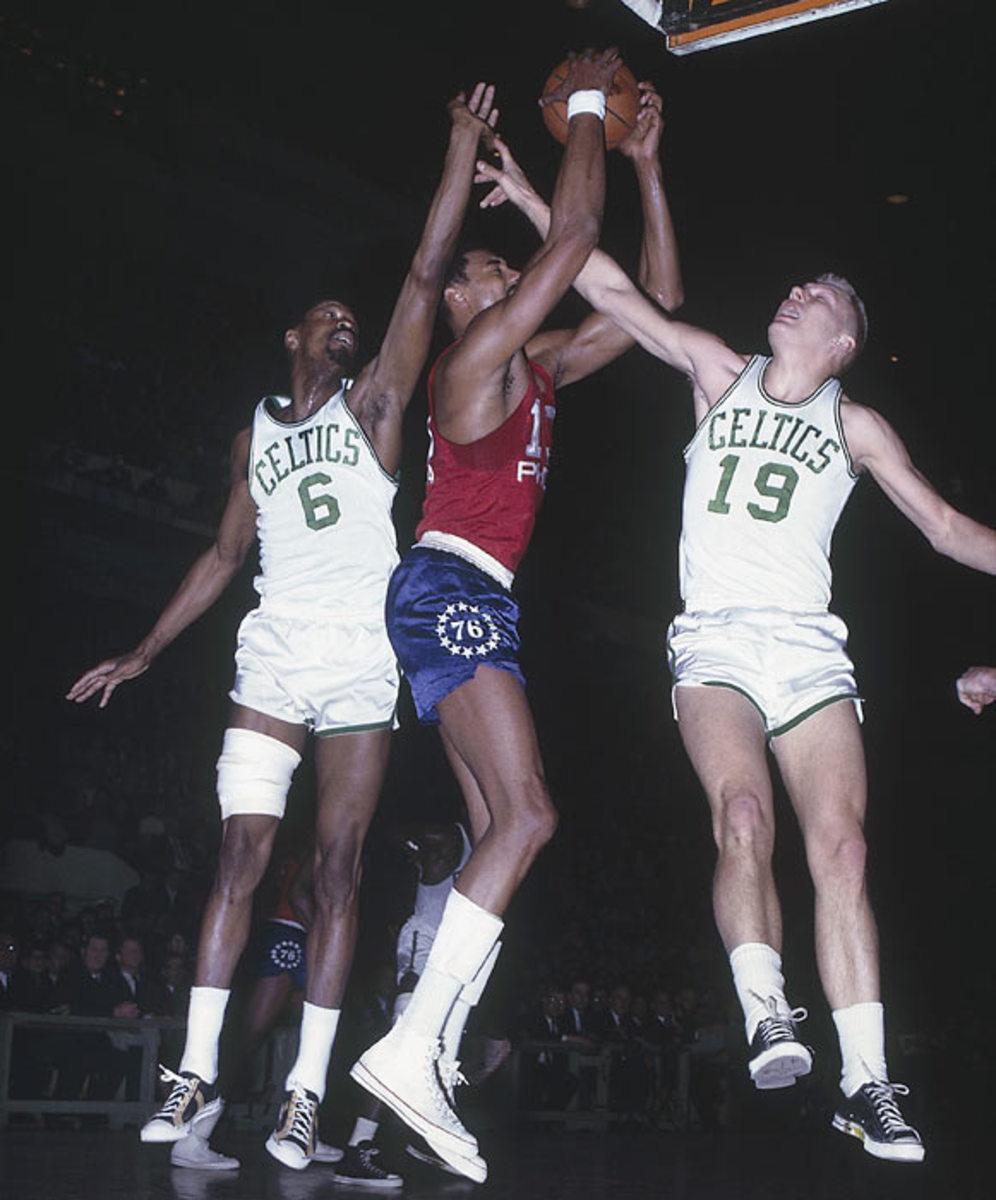

Levi was born on Jan. 27, 1965. Nine months earlier, in the spring of 1964, Chamberlain led the San Francisco Warriors past the St. Louis Hawks in the Western Conference finals, only to lose to Bill Russell and the Boston Celtics in the NBA Finals. After the Warriors’ Game 7 victory over the Hawks, Chamberlain, his teammate Tom Meschery and others celebrated in clubs up and down Broadway in San Francisco. It was a time of social and political ferment. The Beatles had just come to the U.S.; long-held notions of race, sex, love, war and religion were being challenged.

• MORE NBA: James Harden, the NBA's unlikely MVP candidate

Chamberlain was a commanding presence. “Wilt always wanted anonymity,” Meschery said, “but he never could get it because of his height and because of who he was and because he was [even] larger in his presentation of himself.” Meschery recalled Chamberlain’s showing up for a Warriors practice with his two dogs on leashes. He wore a flamboyant shirt open to the chest and “matching slacks, Egyptian gold chains, and sandals,” Meschery said. “I thought, Jeez, Wilt, if you want anonymity you better dress differently. You might want to wear an old brown suit and hunch over a little bit.”

On June 8, 2004, after a year's wait, Levi received the papers with background information about his birth parents from the Santa Clara County Social Services Agency. The details, obtained in 1965, were said to be entirely from his birth mother. She was described as a single, white, 26-year-old secretary of English-French descent who had been raised in England. Levi’s biological father was a single, 28-year-old black professional basketball player with black hair, brown eyes and bronze complexion, 6' 10", 240 pounds, born in Kansas, with a master’s degree.

Not all of the facts lined up. Chamberlain was a native of Philadelphia. He had attended the University of Kansas for three years without earning an undergraduate or master’s degree. The papers indicated that Levi’s biological parents had only a “casual relationship” and that the mother wouldn’t provide the father’s identity because she “wanted to protect his name.” The case files also indicated that Levi’s “birth mother felt that she could not raise a bi-racial child, especially because of . . . the values she was exposed to as a child who grew up in England.”

In 1964 the only San Francisco Warrior who was African-American, 28 years old and at least 6' 10" and who had ties to Kansas was Chamberlain. Then there was the young Levi’s physical resemblance to Chamberlain. Levi’s older sister Naema Clark, living in Oregon and also searching for her biological parents at the time, commiserated with him. “Aaron is someone who takes everything literally and personally,” she said. “He’s guarded [and] overly thinks through a lot of things.” She told him about a website that deploys volunteer “search angels” with database experience to help link adoptees with their biological parents.

In April 2009, after obtaining his birth certificate with his mother’s maiden name on it (his father’s name wasn’t noted), Levi went to the website recommended by his sister and posted that he was seeking help to find his birth mother. He included her name. He also wrote, “From the research that I have done, I think my father could have been Wilt Chamberlain.”

Launching a database pursuit in England using birth indexes, one search angel quickly located a likely candidate. (Out of respect for the privacy of the adoptive process, I have agreed to call Levi’s biological mother Elizabeth, not her real name. She told Levi she could never be interviewed about the circumstances of his birth or adoption.) Another search angel, without Levi’s permission, then made a deceptive post on the website of a newspaper published in the city where Elizabeth was born. On a “Lost Loved Ones” message board the search angel wrote, as if she were Levi, “I think enough time has passed that it’s ok for her family to know about me . . . I was adopted by a wonderful family and only wish to meet my biological mother.”

One of Elizabeth’s relatives still living in the area read the post and contacted Elizabeth’s brother. Days later Levi received an email from him. Elizabeth’s brother expressed shock over the post. He told Levi that he’d just phoned Elizabeth, and she was furious about the public nature of the Internet post and wanted it taken down immediately. Levi was angry with the search angel. “Her method was dangerously destructive,” Levi told me, “but it worked.”

His uncle’s email conveyed warmth, which gave Levi hope. He encouraged Levi to call him, so he did. The uncle told Levi that he’d phoned Elizabeth and asked, “Do you have a secret you’ve been keeping from me?” Her response: “How do you know about that?” The uncle said that Levi had many relatives who, no doubt, would like to meet him. Then he added, “By the way, you are right about who your father is.” He said Elizabeth was confused as to how Levi could’ve known about Chamberlain’s paternity because she had told hardly anyone.

• MORE NBA: How Steve Kerr transformed the Golden State Warriors

Later that day Levi spoke by phone with Elizabeth. “My heart was pounding, racing, nervous, just a surreal moment,” he recalled, “talking for the first time to the woman who gave birth to me, hearing her voice, and then of course to hear that she sounded like an Englishwoman.”

Levi said she confirmed that she was his biological mother. They spoke for more than an hour. Elizabeth had been married for more than 30 years, with no other children. She confirmed that Chamberlain was Levi’s father and asked how he knew. Levi explained how the Santa Clara County records had all but identified Chamberlain.

Elizabeth told him the story of how she first met Chamberlain. She said that she and a girlfriend who knew Chamberlain went with a group to a jazz club in San Francisco, and she was introduced to him. He asked for her phone number. They went out a few nights later, she had too much to drink, and they ended up at Chamberlain’s apartment. That night Aaron was conceived, she said. Elizabeth said she never saw Chamberlain again.

Through subsequent emails and conversations, Levi learned that when Elizabeth awoke the morning after her date with Chamberlain, she was no longer in his bed but back in her own bed at home. She said she called him about five months later to tell him that she was pregnant, that only he could be the father and that she planned to put up their child for adoption; then she called him after their son was born to reconfirm her intentions. The Santa Clara County documents indicated that biracial children were “considered to be hard to place” in 1965—Aaron spent his first six months in foster care—and that his biological father had made financial arrangements to help his mother “get on her feet.” (He did not, Elizabeth told Levi.)

Several years later, Elizabeth learned from a phone call to Santa Clara County that her son had been adopted by a fine family in Oregon. That eased her mind, she told Levi, and she went on with her life, still keeping his birth a secret from her family.

Aaron and Elizabeth met for the first time in the autumn of 2010 in Boston, at the apartment of his aunt Vicki Levi. He said he paced nervously before Elizabeth’s arrival, wondering what to say and how to put her (and himself) at ease. When she arrived, he hugged her at the doorway and said, “Oh, my God, this is the moment I’ve been waiting for my whole life.”

She became emotional, turned away and said, “Don’t say that. You’ll get me going and I won’t be able to stop.”

Outside, rain fell as they sipped tea in the living room. They spent the afternoon in upbeat conversation, never mentioning Chamberlain. But when they met a couple of days later he felt the mood was right.

“Were you friends with him?” Levi asked.

“No, we were not. It was really just two days.”

“What was he like?” he said.

“He seemed very charming, but I really can’t remember.”

She was hardly a groupie, Levi told me. She knew nothing about basketball or U.S. sports. She knew little about Chamberlain’s history. “He’s dead, isn’t he?” she asked Levi at one point.

“It’s hard to accept that you are a product of a one-night stand,” Levi told me. “I wanted her to tell me something good about him, but that wasn’t going to happen. I realized that we had different feelings about him. She sees him as a womanizer. . . . To me, he’s my father.”

[pagebreak]

Vicki Levi returned to her apartment late that afternoon and met Elizabeth. “They were still sitting on that couch six hours later, still talking,” she said. “She is a very, very lovely, gracious woman, charming, soft-spoken, not loud like we tend to be. She is the kind of woman you would like to meet again. I see her as a victim of so many things—her own attractions, her naiveté, her time.”

Aaron Levi shared with me emails Elizabeth sent him, each one signed Bisous (French for Kisses). He showed me a photo of Elizabeth in the 1960s that his uncle had sent, and Levi said she looked like a young Joanne Woodward. He showed me more recent photos of her as a 76-year-old woman. He let me hear messages she had left on his phone answering machine in her small British voice; he has saved every message she left him, no matter how brief. In one email she said that if he felt the need to go public, he should go ahead.

Aaron and Elizabeth met again last fall, in London. They went to art galleries together and shared long conversations in which they found common interests. (Both watch Downton Abbey.) They rode the London Eye, a huge Ferris wheel beside the Thames. She didn’t want Levi to meet her nieces and nephews—his cousins—and that bothered him. He told me it made their relationship feel conditional.

He had thought a lot about Wilt and Elizabeth and their brief interaction, and he desperately wanted to know how Chamberlain responded when he learned he had fathered a child. Was he helpful? Sympathetic? Compassionate? Levi said he finally asked Elizabeth about it over breakfast one morning in London.

“Well, he kind of chuckled,” she said, “and said, ‘Oh, so I’m gonna have a kid out there, huh?’ ”

“Did he offer you help?” Levi asked.

“No. I was very clear about what I was planning to do.”

“I think,” Levi told me later, “[Chamberlain] probably realized that he had lucked out, that she was not the type to seek something out of it. My mother took the burden completely on herself to take care of this problem of an unwanted child.

“[Elizabeth] is, at least to me, a delicate little woman who I am asking to dredge up something that is to me super important, the genesis of my life. For her, it’s related to the biggest mistake of her life. I just have to see the difference in where we are coming from.

“I’ve got something between perfection—which would be total acceptance—and total rejection. . . . Although I don’t like the idea of secrets, I suppose I am having a secret relationship with [Elizabeth]. I guess I am taking what I can get. Am I super happy about it? No. But that is where we are, and I don’t know if that will change. She is in her late seventies, and this has been a secret for 50 years. I think she likes me enough, and if I were a different type of person, she might not accept me. To be ignored is devastating.”

The Chamberlains have ignored Levi, he said. But last summer I persuaded Seymour (Sy) Goldberg, Wilt’s longtime attorney, to see us at his Marina Del Rey law office. Levi showed Goldberg a photo on his phone of Elizabeth from the 1960s and said, “She is kind of the type that [Chamberlain] liked, I think.”

Goldberg said, “He liked all kinds. Don’t limit it. They had to be young and cute, O.K.? That was the criteria.” The octogenarian lawyer sat back in his chair, his right index finger laid against his temple, and listened to Levi’s narrative. Goldberg was friendly, playful, a good schmoozer, the ultimate Chamberlain loyalist. He wore a gold bracelet and a loose-fitting Tommy Bahama shirt that revealed gray chest hair. On the wall beside his desk was an old photo of himself sitting between Chamberlain and Muhammad Ali.

Over four hours, Goldberg fondly shared many stories about Chamberlain and their friendship of more than 30 years. “People don’t stay married that long,” he said. Until now, he said, no one had come forward to say he or she was Chamberlain’s child. “From time to time,” he added, “it would occur to me that [Chamberlain] was pretty damn lucky. Maybe he took extra precautions.”

Levi offered to sign an agreement that he would never make a financial claim. Chamberlain bequeathed more than $6 million, much of it to children’s causes, and $650,000 to his alma mater, Kansas. “I don’t think that’s the issue,” said Goldberg, who was the executor of the will. Besides, he added, “everything is gone.”

Levi said that when he called Wilt’s sister Selina Gross, she told him not to call again, and that Wilt’s other surviving sister, Barbara Lewis, did not respond to his letter. “I have no reason to disbelieve your story,” Goldberg said of Levi’s claim to being Chamberlain’s son, “but how do I know?”

Levi said the Chamberlains could confirm his blood connection “by doing the [DNA] test.”

“Why should they?” Goldberg said.

Two hours later, sitting in her office at an aquatic therapy center in West L.A., Lynda Huey turned her chair to face Aaron Levi. “Give me a moment,” she said as she put on her glasses to read the Santa Clara County non-identifying information. It didn’t surprise her to see the mention of a master’s degree. “Wilt lied a lot when he was meeting women,” she said.

• MORE NBA: Jimmy Butler's rise from homeless teenager to NBA star

Huey, blonde, trim and fit at 67, met Chamberlain in 1971 and became a part of his world. They were lovers for years, though near the end of his life they were only friends. She worked with him as an aquatic therapist, helping him recover from elbow, hip and knee surgeries. She was with him on the last Saturday night of his life, watching Shakespeare in Love with him in his bedroom in Bel-Air.

Levi told Huey how Elizabeth woke up in her own apartment, not remembering how she’d left Chamberlains’s place. “She didn’t even remember the sex?” Huey asked.

“It’s a blur,” Levi replied. He suggested that Chamberlain had taken Elizabeth home and tucked her in out of kindness. “Well, two things,” Huey replied. “It’s kindness, but he was also making sure that she didn’t wake up in his place and he would have to deal with it. Wilt was the getaway king.”

As for Levi’s belief that he is Chamberlain’s son, Huey said, “I’ll give you the reasoning why someone might not believe you. [A white woman] knows that she is pregnant with a black kid, and she knows the kid is going to be tall. It could be any tall black man anywhere. What’s the best thing that she can say? ‘It’s Wilt Chamberlain’s.’ That’s the get-out-of-jail-free card.”

But Levi noted that Elizabeth was from a different country and didn’t even know who Chamberlain was. She mentioned his name only when Levi found her nearly a half-century later.

“I think he wanted to be a father,” Huey said of Chamberlain. “Several times he and I went out to look at properties together. He wanted to set up a place where he could raise a bunch of kids.” She said he wanted to adopt either black or mixed-race kids.

I asked Huey if she believed that Levi is Chamberlain’s son. “I want to believe it, but I’m not sure,” she said.

“Do you think I look like him?” Levi asked.

“I think you looked tremendously like him when you were 16,” she said.

“I want to look at your hands,” Huey said. Levi placed his right hand in her palm. She examined it closely, lovingly. “You have thumbs like his,” she said. “I loved Wilt’s hands.”

Months later I reached Barbara Lewis, Wilt’s sister, by phone at her home in Las Vegas. Among family members she serves as lead custodian of her brother’s legacy. “He and I were very close,” she said. “Extremely close.” When Goldberg first told her about Levi and his desire to meet her, she said she told him, “Sy, I’m not interested. Wilt’s dead.”

She hasn’t changed her mind. “I’m not interested in meeting him because I just don’t believe it,” she said. Nor is she interested in seeing photos of Levi. “He’d have to look very much like Wilt,” she said. “That is a distinct look. I can’t even imagine that.”

I explained that Levi has been on a long journey of self-discovery. “Which I can understand,” Lewis said. “Everybody wants to try to figure out who they are.” If Wilt were still alive, she said, things would be entirely different: “Probably this young man would have written to him. It wouldn’t be for us to get involved, especially since we are the last two [siblings] in a family of 11.”

Her voice rose in defense of Wilt: “I don’t understand why this is important when he is gone. What difference does it make now?”

I described Elizabeth, how she met Wilt at a club in 1964 and how she knew nothing about basketball. “For her to say it was Wilt, it could’ve been anybody,” Lewis said. “She didn’t know him.”

I asked if anyone else had ever claimed to be Wilt’s offspring. “Not to me,” Lewis said. “Never.”

I said, “The only scientific proof. . . .”

She finished my sentence: “. . . is DNA. I’m certainly not giving up DNA.” If she were to do so, she explained, it would be “without [Wilt’s] O.K., and I wouldn’t do that. I don’t want to be involved in it.”

Wilt’s other surviving sister, Selina Gross, did not return phone messages.

In A View from Above, Chamberlain left these thoughts for Aaron Levi to ponder:

Any idiot can father a child, and too many of them do.

I believe in adoption and doing as much as we can for the kids who are already here.

“Painful,” Levi said. “He knew that I was put up for adoption. That hurt.”

Harriet Levi, his adoptive mother, said, “Aaron has a right to say, ‘Here I am, don’t hang up the phone on me, world, because I exist.’ ”

Meschery said, “It seems highly possible that Wilt fathered a child. I’m surprised there aren’t more. But I can understand the Chamberlain sisters’ not wanting any part of it. They are very protective of their brother. My experience with Barbara is that she is a very kind and loving woman and very much attached to her brother. I think Aaron has gone as far as he can go. He knows who his father is and who his mother is. If he can get a relationship from his mother’s side of the family, that’s 50% of the battle. . . . Trying to get Wilt’s family on board, in my opinion, it’s not going to happen.”

Levi’s 50th birthday has passed. He doesn’t want to wait another decade to complete his odyssey. “I’ve been burning with this for 10 years now, so I feel like I’ve got to try now,” he said.

In his research Levi found several of Chamberlain’s nephews on Facebook. Maybe one would understand his quest and share DNA. So far, though, fearing more rejection, he hasn’t tried to contact them.

By going public with his story, he said, he’s reaching out not only to those he believes are his blood relatives but also to all adoptees. He hopes his story moves adoptees to begin their own searches earlier. “My life would be completely different,” he said, “if I had done this 20 years ago, when Wilt was still alive.” He has imagined a conversation he would have had with Chamberlain: “ ‘Do you remember my mother? Do you remember her telling you that she was pregnant?’ Depending on his answer to that, I would go further.” He paused. Softly, he said, “I would ask, ‘Have you thought about me over the years?’ ” ±

Gary M. Pomerantz is the author of WILT, 1962: The Night of 100 Points and the dawn of a New Era.” Follow him on Twitter @GaryMPomerantz and on Facebook.