SI Vault: How a coin flip helped the Milwaukee Bucks land Lew Alcindor

Editor's note: Before he changed his name and became known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Lew Alcindor was a star on the UCLA basketball team, where he won three consecutive national championships and was a record three-time MVP at the NCAA tournament. From the March 9, 1970 issue of SI, we look back at a pivotal moment in the NBA when the Milwaukee Bucks and the Phoenix Suns conducted an over-the-phone coin toss to see who would get the first pick in the 1969 NBA Draft—and ultimately, UCLA's star center, Alcindor.

When the Milwaukee Bucks and the Phoenix Suns flipped a coin for first choice in the NBA draft last March, Lew Alcindor was the obvious prize. The Suns called heads, the flip came up tails, and in Milwaukee where Wes Pavalon, the principal owner of the Bucks, and John Erickson, the vice-president and general manager, were listening to the result by telephone Pavalon embraced Erickson so exuberantly that he jammed his lighted cigarette into Erickson's ear.

"It stung a little, but I didn't notice it," Erickson said recently. "I didn't care, once we had Lew."

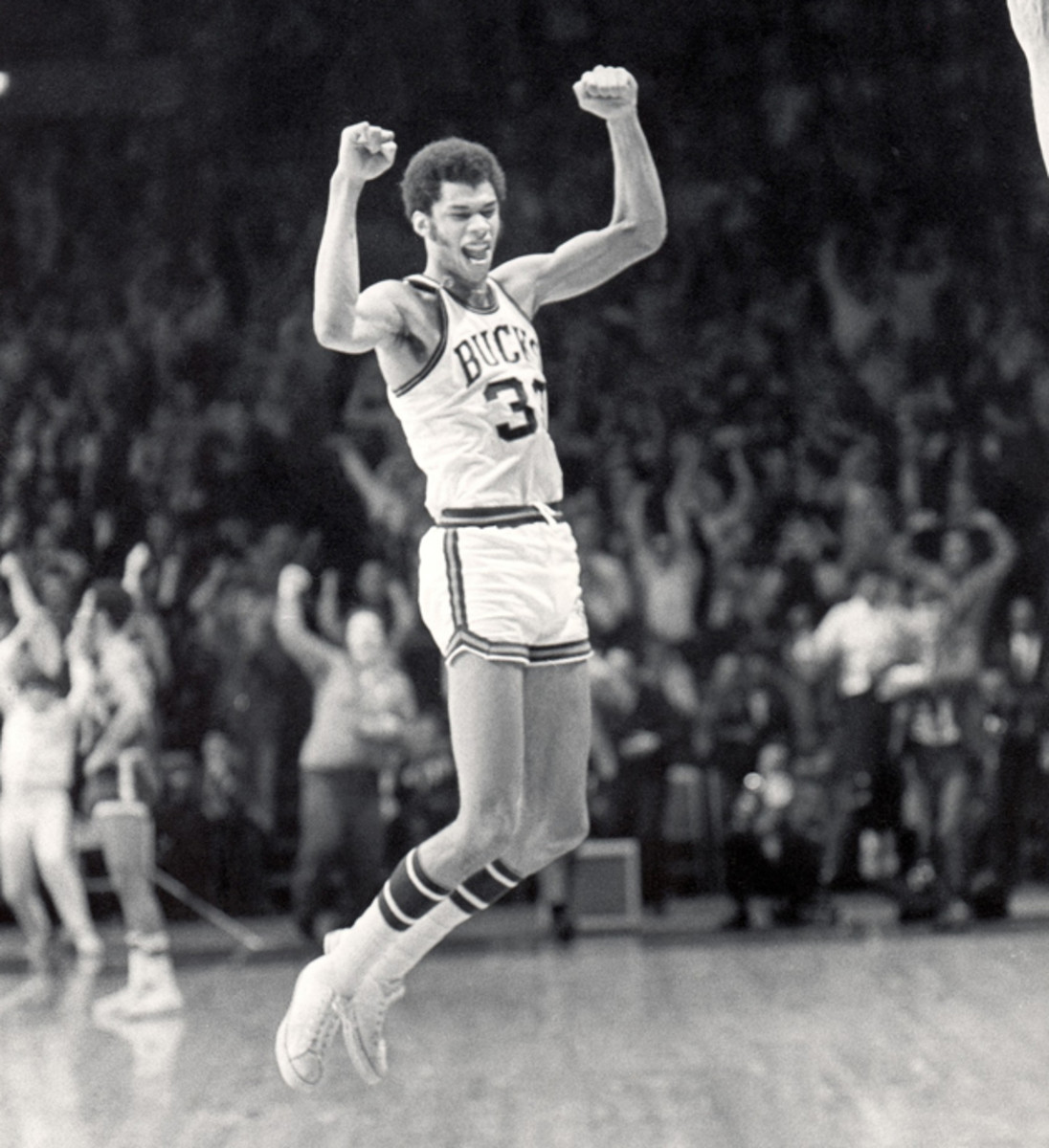

His enthusiasm is understandable. The Bucks, with no Alcindor, finished in the cellar last season; this year they are in second place. With six home games to go in the regular-season schedule as of last week, gate receipts were $1.2 million—more than twice the $546,537 total for the entire 1968-69 season. And this year there will be playoff money, too. Milwaukee attendance is about 3,000 more per game than last year, despite the fact that the top price for tickets was raised from $5 to $7. The Bucks' receipts are the NBA's third highest, behind only New York and Los Angeles, both of which have far more seats than the Milwaukee Arena's 10,746.

• MORE SI VAULT: 60 years, 60 iconic stories from Sports Illustrated

Stock in the Bucks—traded over the counter—has gone from $5 to somewhere between $12 and $13 a share. In the bars in Milwaukee, during the sere months from January to September, talk used to turn on how the Green Bay Packers would do in the year to come. Last week bartenders and customers alike were more concerned with whether or not the Bucks could 1) catch the Knicks before the season ends or 2) win the playoffs in any case. The rise in receipts, the jump in the stock, the shift in the talk—all have been caused by the presence of one man.

Lew Alcindor is not the first of the magnificent giants of basketball, but he is easily the best today and will soon be the best ever. He will not change the style of the pro game, because Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell have already done that with similar though lesser physical endowments. But he dominates it (see cover)—every game in which he plays—and the thoughts of rivals before and after they meet him.

Long before Alcindor graduated from UCLA last year, pro basketball had made the rule changes dictated by the size of Chamberlain and the virtuosity of Russell. The restraining line under the basket had been widened and offensive goaltending was forbidden. Lew himself had changed college basketball, taking away its most spectacular offensive weapon; the NCAA made it illegal to dunk the ball, since Alcindor could dunk without leaving his feet. Still, there are no rules which can effectively inhibit a man like Alcindor.

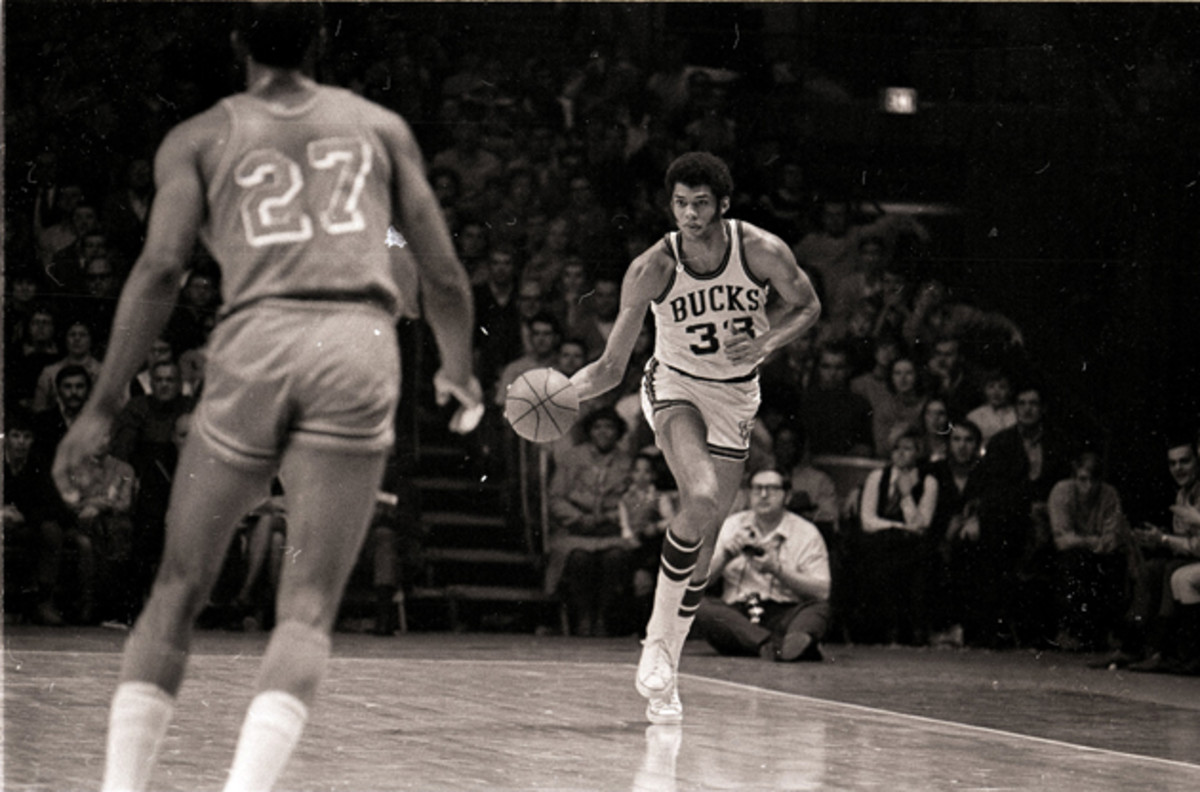

"He may be the first of the 7-foot backcourt men," says his teammate, Fred Crawford. "He can dribble and make moves that no big man ever made before. Russell could dribble straight down the floor, but Lew can bring the ball down and handle it and give you fakes, and no one his size could ever do that.

"If all Lew had to do was play defense, he could do it as well as Russell. He has all Bill's quickness and he's much taller. Offensively, he's a better shot than Chamberlain and he moves. Wilt used to go into the post and lean on people, and when he leaned you couldn't do much about it. Lew's not that strong, but he can put the ball down and beat you with speed and agility, and Chamberlain couldn't do that. And he has more shots than Wilt. I think that banning the dunk when he was in college may have been the best thing that happened to him. It took away an easy shot for him, but it made him learn other shots, and now he's a versatile shooter. And in the pros he can still dunk the ball."

Guy Rodgers, who played six seasons with Chamberlain and 11 against Russell, and who, at 34, is playing out his string with Milwaukee, feels that Alcindor is unfortunate in not competing against the other giants. (Russell is retired, Chamberlain has been out most of the year because of a knee operation and Nate Thurmond, also injured, has said he may never play again.) "Lew would have learned a lot against the Goliaths," says Rodgers, "and the fans would have seen some great old pros and the heir apparent. Lew would have looked even better against great centers. He still has competition from a center like Willis Reed—a guy who is all fire and brimstone. But I would have liked to see him with Russell and Chamberlain, too.

"He's agile and flexible, and he can play a low or a high post, so we have patterns both ways. And he's great at setting up a play from a defensive rebound. He can lead you with a pass to start a break as well as anyone.

"On defense you play differently with him in there. He's no Russell yet, but Russell was the greatest defensive player who ever lived. The Celtics depended on him so much that the other players didn't play defense as well as they could. K.C. Jones could have been even better than he was, but in Russell he had the Great Eraser behind him and he could take risks he wouldn't take normally. That's what we have in Lew. We take chances because we know Lew is there."

Gambling on defense may not make the Bucks better individual players, but the tactic can drive a rival team to distraction and to neglect of its normal style. On offense, each Milwaukee player also has an added edge over his defender because of Lew—every opponent has to give part of his attention to the big man. And when he is double-teamed, Alcindor hits the open Buck, often with a pass thrown like a baseball.

• MORE NBA: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on storytelling and more in Q&A

The problem of how to handle Alcindor has spread headaches around the league. The Lakers do as well as any team, but not because they have their own 7-footer, Mel Counts, to play Lew man-for-man. Laker Coach Joe Mullaney makes no secret of his strategy, possibly because it is only occasionally effective. "We try to keep their guards coming down the middle of the floor," says Mullaney. "If you let them come down the sidelines, with Lew playing a low post on one side or the other, you're dead. Once the pass gets in to him, it's two points. So we make them come down the middle, put Counts in front of Lew and keep him from getting the ball. And we give Counts help."

In a recent game, against this strategy, Lew gave Counts a quick fake one way, rolled the other way with two swift, mincing steps, took a pass from a teammate and went up to dunk the ball. The move was deceptive and graceful. When he is allowed to take the pass from a guard at the sideline, his move is just as quick and deceptive. Then he lifts himself easily and shoots a surprisingly soft, accurate hook that comes from so high that no one can block it.

"I got caught in a switch once under the basket when he shot that hook," says Crawford. "I looked up to see where the ball was, and Lew's hook looked like it was coming down from outer space."

When he is moving to the basket Lew's power is a weapon in itself. Last week, against Baltimore, he received a pass behind Wes Unseld and went in for a stuff shot, and Kevin Loughery rashly decided to get in his way. As Lew leaped, his right knee—drawn up—slammed into Loughery's rib cage. It was five minutes before Loughery recovered sufficiently to be helped out of the Arena. He spent four nights in the hospital with three broken ribs and one cracked rib.

In the same game Baltimore's Ray Scott, who is 6'9", got off a jump shot over the outstretched hand of Milwaukee's Don Smith, also 6'9". As the ball cleared Smith, Alcindor was five feet further away from Scott but he soared straight up and blocked the shot. And he did it with so much force that he knocked the ball from the free-throw area back over the midcourt line.

So far this year Alcindor has played nearly 150 minutes longer than anyone else in the league. It is an indication of his stamina and ability to take constant battering, despite the fact that centers, traditionally, have impressive playing-time records. Milwaukee Coach Larry Costello explains: "It's easier for a center to last. They come down the middle of the court and they don't move as much as guards or forwards. They're only about half as active. But Lew is different. He's probably the most active center in the game. He moves from a low to a high post, from one side of the lane to the other. He brings the ball downcourt when he has to. He exerts far more energy than most big men. Even when we get the ball in to him on the post, he herky-jerks around and uses moves—not just muscle—to work in. But he doesn't get tired. You know a funny thing? He's gained weight during the season."

Possibly because of the hectic pace, Alcindor has yet to evaluate the impact pro basketball has had on him. "I came into it with an open mind," he said the other day in a hotel room that looked undersized for his 7-foot-plus, 230-pound frame. "I didn't think I'd be able to play as much as I have, but that was because I believed what I had heard about how tough it was. I don't know if it is as much fun as college ball—I'll have to reflect on the season when it is over before I can decide. Right now it's hard work. I didn't expect to be able to take the pressure day in and day out. I've already played almost as many games this year as I played in all three years at UCLA, but I'm not tired. I've learned to take a breather now and then and get back into the flow of the game. I took those notes from Bill Russell. I used to watch him, and sometimes he wouldn't even come downcourt when the ball changed hands. He knew the game very well.

"I wish I could have played more against a guy like Nate Thurmond. I played against him three times, and it was like a laboratory. I didn't pick up much from him, because he doesn't play the same way I do, but I learned things about my own game—the good things and a few faults—and the mistakes I make against a player like him.

• MORE VAULT: Westbrook is doing what Larry Bird did 29 years ago

"I didn't learn anything from Chamberlain the one time I played against him. I used to watch him when I was a kid, and I had this picture of him in my mind as Superman. Then I played against him for the first time in the Maurice Stokes Benefit Game—and he isn't. I can't learn from him because he is so different from me. You always know what he is going to do, but he is so strong, you can't keep him from doing it. I learned a lot about defense watching Russell. I'd watch the way he positioned himself for rebounds and the way he blocked shots, and it helps.

"I got psyched by the officials early on blocking shots," he adds frankly. "I got a lot of calls for goaltending, and I got to the point for a while where I wouldn't even try to block a shot. I'd just try to maneuver for position and get the rebound and let my man shoot. You have to overcome that, but it isn't easy to do. I'm trying to do it now, but I still get goaltending calls. I can't judge if I have improved on that or anything else yet because I can't look at myself objectively. Someone who saw me early in the season and didn't see me again for a long time is in a better position to make that judgment."

One rival who prefers anonymity has made it, quite succinctly: "He's a whole new force. He doesn't even know how good he can be. If he finds out before the playoffs start, God help the Knicks. And everyone else."

This story originally ran in the Mar. 9, 1970 edition of SI. To subscribe, click here.