Russell Westbrook opens up: All there really is to the Thunder superstar

This story appears in the April 6, 2015 issue of SI. To subscribe, click here.

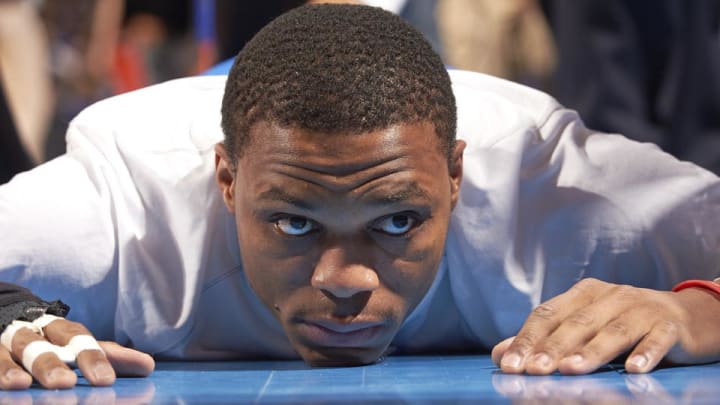

When Russell Westbrook finishes the orange wedges, the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and the Taylor Swift and Katy Perry songs, he sits swaddled in white towels, his terry-cloth cocoon. He stretches out over two chairs in the Thunder locker room, his iPod with its eclectic playlist resting on his right thigh, and lets the metamorphosis unfold. “He doesn’t talk,” says guard Anthony Morrow. “He doesn’t blink. He turns into Maniac Russ.” He stares at a wall-mounted TV flashing video of that night’s opponent. Teammates try to engage him. “But he’s somewhere else,” Morrow says. They ask questions and then reconsider: “You know what, man, it’s nothing,” says second-year center Steven Adams. They follow him to the floor, where the transformation is completed. “The ball goes up,” Adams says, “and he becomes a beast.”

Before Westbrook blossomed into America’s fast-twitch phenomenon, before he piled up triple doubles at a rate that recalls Oscar Robertson, before he could do virtually everything on a basketball court—leading the NBA in scoring, ranking fourth in assists and second in steals through last Saturday—he could do only one thing. “I wasn’t that good,” Westbrook says, “but I played hard.” When he was a junior at Leuzinger High in Lawndale, Calif., the age by which most headliners have already been anointed, he couldn’t dunk. He couldn’t shoot. The only interested college was San Diego. An honor-roll student, he believed an academic scholarship was more attainable. “I have one friend,” Westbrook told himself before games, “and that’s this ball.” He had to seize it, cradle it, compel it to carry out his will.

In 2004, UCLA hosted a small-time AAU event that Bruins coaches were not allowed to attend. But a tournament organizer charged into the basketball office at the Morgan Center and hollered, “There’s some little 5'10" kid flying around Pauley Pavilion like a bat out of hell!” That was Russell Westbrook, bat out of hell. Much has changed since then—his body, his style, his stat line—but not his spirit. He is still the 16-year-old striver whose parents worked at a bread factory and a school cafeteria. On the balcony of the family’s South L.A. apartment, they installed a dip bar over a sandbox, and Westbrook did pull-ups until his arms throbbed. He grew into a spring-loaded UCLA sophomore who declared for the draft and tried to break the rim in his audition with the then Sonics. “His wrists,” says trainer Rob McClanaghan, “were red afterward.” Where Westbrook once bounced off gym walls as a way to inspire his younger brother, Raynard, he now works up the same lather because the sports world is watching, waiting, holding its breath for the kinetic feats of Maniac Russ.

• MORE NBA: Westbrook appears on national cover of Sports Illustrated

“There are many times throughout a season that you may not feel like playing,” says Westbrook, 26. “You may not want to play on this night, or against this team. But I don’t feel that way. This is one of the best jobs in the world, and you never know how long you’ll be able to do it—how long you’ll be able to run like this and jump like this. So I go for it. I go for it every time. It may look angry, but it’s the only way I know.”

He grabs a rebound or accepts an outlet pass and reduces myriad options to one. “Attack,” he tells himself. He hears opposing coaches bark, “Load up,” and he realizes reinforcements are coming. “That doesn’t stop me,” he says. “That makes me go after it even more. I want to mess up their game plan.” At half-court he takes a mental snapshot of the floor. The first defender might as well go grab a swig of Gatorade. “My mind-set is, I can get by anybody in front of me,” says Westbrook. He is focused on the next line of defense, which will pressure him into a decision. Does he pull up at the elbow for the 15-footer he calls his “cotton shot” because it’s so comfortable? Does he kick out for the three-point snipers who are panting to keep up with him? Or does he summon all his fury and hurdle whatever giant awaits on the back line? “I have fears,” Westbrook says, “but I do not fear anything or anybody on the court.”

He stands only 6' 3", but he packs 200 tightly coiled pounds onto that modest frame, and he can finish violently on both sides of the hoop because he is essentially ambidextrous. He writes and eats with his left hand, shoots and throws with his right. Both arms are striped with scars acquired from collisions in the lane. By the time he reaches the basket he looks ready to combust, face contorted into a delirious grimace. “I used to hold in my emotions and then I’d have one big outburst,” Westbrook says. “Letting them go helps me move forward.” Later he will watch himself on video and see a stranger, screaming, chest-thumping, brandishing imaginary pistols. “A crazy man,” Westbrook says. “I don’t even know what I’m doing.” When he walks to the free throw line, he reminds himself to breathe: “After an and-one, I’m screaming so loud and my adrenaline is so high, I can’t really calm down.”

Trends: Russell Westbrook finally has Thunder in postseason driver's seat

The wrath of Westbrook is contagious. “He plays with a rage,” says Thunder small forward Kevin Durant, “that ignites this whole team, this whole arena.” Westbrook has stirred Oklahoma City since he entered the NBA six years ago, but he was often dismissed as Durant’s roguish sidekick, chided for stealing shine from a superior. Now, with Durant out for the rest of the season because of a lingering right foot injury that requires bone-graft surgery and power forward Serge Ibaka recovering from a right knee operation, Westbrook is enrapturing the league and dragging the Thunder to the playoffs by the scruff of their neck. He is on pace to average more than 27 points, eight assists and seven rebounds, a threshold that has been eclipsed only by Michael Jordan, LeBron James and Robertson. Before the All-Star Game at Madison Square Garden, the Big O called him over. “I told him he’s a helluva player,” Robertson says. Westbrook scored 41 points in 26 minutes that night, winning MVP, and he averaged a triple double in his first 10 games after the break. “I’ve seen others with the same size and physicality,” Robertson says. “But they don’t have his determination.”

When Westbrook tore the meniscus in his right knee during the second quarter of a playoff game two years ago, he still worked the second half, scoring 16 points. “I guess I did feel something,” he acknowledges. When he broke a bone in his right cheek in February in a collision with a teammate’s knee, he underwent surgery the next day and returned less than a week later, racking up 49 points, 15 rebounds and 10 assists while wearing a plastic mask with straps that come unhinged every time Westbrook does. He fidgets endlessly with the mask, but the truth is that he likes it. “We’re talking about a guy with the athleticism of LeBron and the drive of Kobe,” says an opposing head coach. “That’s an intimidating enough combination, and then you put that mask on him, he’s something out of a movie.”

• MORE NBA: Trends: Knicks | The Craft: Z-Bo | Power Rankings | Mailbag

Westbrook’s superpower is hard to measure or define. Nick Collison probably comes closest. “His give-a-f--- level,” the Thunder forward says, “is very, very high.” Westbrook’s passion is a powerful tool, which when harnessed can be empowering and when unchecked can be isolating. “I’m so emotional and I want to win so badly that it can backfire,” Westbrook says. “Controlling it, using it to my advantage, has been the challenge.”

College coaches who scouted Westbrook at Leuzinger High in the mid-2000s found reasons not to recruit him. Small . . . inconsistent . . . immature . . . chicken without a head. Kerry Keating heard all the critiques. “Who gives a s---,” Keating thought. “Nobody will ever stay in front of him.” Keating, then a UCLA assistant and currently the Santa Clara coach, faced little competition for Westbrook. The Bruins landed him even though they couldn’t offer a scholarship until the spring of his senior year.

[pagebreak]

Westbrook logged two seasons at UCLA, and in his last game the Bruins fell to Memphis at the Final Four. The Sonics, about to become the Thunder, invited several Memphis stars to predraft workouts and asked their opinion of UCLA’s many prospects; the Tigers unanimously called Westbrook the toughest. The franchise picked Westbrook fourth in ’08, fully aware that he wasn’t a traditional point guard, and also aware that the days of the traditional point guard were numbered. Still, some tenets of the position—passing, playmaking, elevating the whole—would endure and have to be learned.

Oklahoma City vets laugh at modern-day characterizations of Westbrook as a runaway train, because this is actually the restrained version. They remember what he could be like before, charging headlong into the key, partaking in one-on-one battles that under-mined the team concept, growing irate with referees and forgetting to run back on defense. Many young players succumb to similar pitfalls, but Westbrook came of age in prime time, with the Thunder a fixture in the postseason and on national TV. His foibles made easy fodder for talk shows. “There were times he’d get in his own world,” Collison says, “and it was hard to calm him down.” Anybody who dropped a pass or blew an assignment could be subjected to the scowl. “Every time he looked at me,” says Adams, “I just apologized.”

Last fall Westbrook watched a video of his reactions to plays positive and negative. He noticed how the Thunder responded to his body language for better and worse. “Let’s say a teammate turns it over, and I’m screaming and moving my hands, you can see in his face that he let me down,” Westbrook explains. “And then, on the next play, you can see the lack of confidence.” The opposite was also true. When he celebrated a teammate for hitting a shot, another bucket often ensued. “I saw how my energy can bring the group very high or very low,” Westbrook says. “It was a huge thing for me, a great thing.” He shared his observations with coach Scott Brooks, a former point guard. “Even if the guy should have caught the pass, you have to take the heat,” Brooks says. “You have to take the blame. You have to tell him, ‘My bad.’”

SI Vault: Russell Westbrook is doing what Larry Bird did 29 years ago

The Thunder started this season 3–12, with Westbrook recovering from a broken right hand, perched on the bench next to Durant. “That gave me an opportunity to sit back and see the game from a different view, see life from a different view,” Westbrook says. “Your team is losing, down and out, confidence is low. I wanted to make them feel better.” He has lifted OKC in ways both obvious and intangible. When center Enes Kanter fumbles a perfect post feed, Westbrook points at himself; Kanter, acquired at the trade deadline from the Jazz, is averaging a career-high 17.6 points with the Thunder. When Morrow misses some three-pointers, Westbrook meets with the marksman over breakfast and discusses ways to set him up; Morrow is shooting 52.1% from three since the break. “Two years ago I’d have been shaking my head,” Westbrook says. “That’s a huge part of my growth.” The 21-year-old Adams is even approaching him at stoppages. “You can talk to him on the court, which is cool,” Adams says. “You just have to time it right.”

No one of sound mind would want to mollify him completely. The personal vendettas Westbrook manufactures against random opponents—Raptors guard Greivis Vasquez, be afraid—are legend in Oklahoma City. He gives the Thunder a psychological edge not unlike what the Ravens enjoyed with middle linebacker Ray Lewis. They know they’re riding with the baddest dude in the room, and he is firmly on their side, dispensing his jet fuel.

Westbrook has always dazzled the Thunder with his aptitude, since the early days when they practiced at Southern Nazarene University and he interrupted drills to tell power forwards where they should stand. Back then Westbrook was an attack guard. Then he was an attack guard who dropped off passes for big men. Then he was an attack guard who kicked out for three-pointers. Today he is an attack guard who creates for everyone.

The trick has been expanding his game without halting it. Most classic playmakers operate at a deliberate pace, allowing them to survey the floor and find cutters. Westbrook’s speed compromises his vision, which is why he takes those mental snapshots at half-court, enabling him to anticipate how possessions will unfold. “He’s thinking, If I make this move, what’s my next step, my next read; what will the picture look like then?” says Thunder assistant Robert Pack. Anybody who drives 100 miles per hour all the time gets in some accidents—Westbrook coughs up 4.4 turnovers per game—but he is cautious by his breakneck standards. “Instead of going right by you, which is what he always used to do, he does sometimes slow down,” says McClanaghan, who has trained Westbrook since he was a freshman at UCLA. “Then he goes right by you.”

Westbrook is a terror, a dervish, a demon. He hears these hyperbolic descriptors all the time. He doesn’t necessarily appreciate them.

[pagebreak]

Westbrook squeezes himself into a third-grade chair at Eugene Field Elementary School and reflects on the hotly contested race for the trophy he has eyed since training camp. “It’s been one of my main goals all season,” he says. “I want it.” There are more predicable candidates, but he continues undaunted in his pursuit of the NBA’s J. Walter Kennedy Citizenship Award. He may have a better shot at MVP, but before rejecting his Kennedy candidacy based on postgame interviews Marshawn Lynch would find chilly, consider that Westbrook’s Why Not? Foundation has created reading rooms at three Oklahoma City elementary schools this season and launched a reading challenge in which students from 78 local schools compete to read for the most minutes.

The ball is not his only friend, not even close. Westbrook is beloved in the Thunder’s headquarters for attending the hockey games, soccer matches and piano recitals of staffers’ children. Every year he sends a pair of Air Jordans and a Jordan-brand sweat suit to each employee. He can be warm (“Get me out there with those people,” he told team p.r. boss Matt Tumbleson after the devastating tornado in ’13, when the guard was still relegated to a wheelchair because of the meniscus) and funny (“Congratulations on your daughter’s birth,” he messaged Tumbleson. “I hear her name is Russellena”). He teaches himself guitar. He handles his own bills. He is never late. But he keeps most personal details concealed. Westbrook is admittedly slow to trust and maintains an inner circle smaller than a keyhole. He met his fiancée, Nina Earl, when she too played basketball at UCLA. Raynard attends the University of Oklahoma and wants to go into broadcast journalism. Russell and Raynard are inseparable with their parents, Russell Sr. and Shannon, still back in L.A.

Russell Westbrook cannot be stopped

Celebrities often change away from cameras and tape recorders, but with Westbrook, the contrast is profound. His raspy voice, short and terse during press briefings, suddenly becomes the loudest and liveliest in the room. “People who don’t know me probably think I’m mad all the time, and with the way I play, they have a point,” he says. “But I’m not Angry Man off the court. I’m a laid-back chill guy.” Given his brazen wardrobe choices, which prompted Barneys New York to sign him as a designer, you’d assume he doesn’t care what the public thinks. But that’s not accurate either. He resents the madman portrayals. He distances himself from Maniac Russ. “It upsets me when little kids hear, ‘He’s so aggressive, you can’t contain him,’” Westbrook says. “My mom hears that, my family hears it, and it makes me seem like I have no control over what I’m doing.”

GALLERY: Russell Westbrook, NBA fashion icon

Russell Westbrook fashion and style

September 13, 2015

September 11, 2015

July 22, 2015

June 27, 2015

June 27, 2015

June 26, 2015

June 23, 2015

June 6, 2015

with Nina Earl

June 21, 2015

June 6, 2015

June 1, 2015

February 15, 2015

February 13, 2015

February 12, 2015

January 25, 2015

October 30, 2014

July 17, 2014

July 16, 2014

June 27, 2014

May 29, 2014

May 27, 2014

May 25, 2014

May 19, 2014

May 15, 2014

May 13, 2014

May 11, 2014

May 9, 2014

May 7, 2014

May 5, 2014

April 9, 2014

March 9, 2014

January 25, 2014

December 14, 2013

November 13, 2013

November 12, 2013

September 11, 2013

September 6, 2013

August 11, 2013

March 3, 2013

February 17, 2013

with Joakim Noah and Kevin Durant

February 15, 2013

September 8, 2012

September 6, 2012

September 6, 2012

June 21, 2012

June 19, 2012

June 17, 2012

June 14, 2012

June 12, 2012

May 29, 2012

May 27, 2012

May 18, 2012

May 14, 2012

July 13, 2011

Robertson will not liken his skill set to Westbrook’s, but he does compare their plight. “For years I heard I was a hard guy to know and I had a chip on my shoulder,” Robertson says, “because I didn’t go on television a lot and I didn’t talk to people I didn’t know.” The Thunder understand Westbrook. They resist every opportunity to edit him. They embrace his 15-footers from the elbow, even though the analytics don’t, because they realize those cotton shots enable dunks and corner threes. “When we’re rolling,” Brooks says, “that shot opens up everything.”

The unfortunate side note to Westbrook’s recent binge is that it’s been made possible by Durant’s absence. Last season, with Westbrook sidelined, Durant reeled off 30 points or more in 12 straight games. This spring it is Westbrook’s turn, and he is at the height of his powers. “I don’t know if it’s the height,” he clarifies, “or the beginning.” Next year Durant will be an unrestricted free agent, and the year after, Westbrook will follow. The clock ticks in Oklahoma City, but Durant is undergoing his third foot surgery in the past six months, suspending championship hopes once again. In 2013 the Thunder missed Westbrook in the playoffs. In ’14 it was Ibaka. Now Durant stands wistfully under the basket at timeouts, hoisting layups in his blazer.

For the moment he has ceded the marquee to Westbrook, who is sitting in his newest reading room at Eugene Field. He has arrived, early as usual, in a gray scoop-neck shirt and tight black pants cut off at the calf. He has sliced another red ribbon with oversized scissors. He has spotted his picture on the wall, fists clenched, eyes aflame. Now he is holding a book called I Like Myself, which the school selected for two third-graders to take turns reading aloud.

I may be called a silly nut

or crazy cuckoo bird—so what?

I’m having too much fun, you see,

for anything to bother me!

Even when I look a mess,

I still don’t like me any less,

’cause nothing in this world, you

know,

can change what’s deep inside, and

so . . .

No matter if they stop and stare,

no person

ever

anywhere

can make me feel that what they see

is all there really is to me.

Lee Jenkins joined Sports Illustrated as a senior writer in 2007. Since 2010 his primary beat has been the NBA, and he has profiled the league's biggest stars, including LeBron James and Kevin Durant.