Look At Me Now, Mom: Mother's Day holds a special place in NBA's heart

This story appears in the May 11, 2015 issue of SI. To subscribe, click here.

They come from Houston’s Third Ward, L.A.’s Compton corridor, small-town Iowa and rust-tough Michigan. They were athletes before they were mothers: tennis players, power forwards, runners. They watched the Showtime Lakers and the Bad Boy Pistons. They loved Magic and Isiah. They got pregnant and, despite challenges, carried to term. They lay in hospital beds, holding their sons for the first time, and remarked on the size of newborn hands. In many cases they raised the boy alone, left to explain why fathers were absent. They bought him his first basketball, signed him up for his first team and filled his bedroom with plastic mini hoops that broke when he dunked. They taught him to shoot and crossed their fingers when he dribbled. They kept his birth certificate in their purse for when other parents inevitably complained that he was too big.

They often made long commutes and worked interminable hours, plus extra shifts, to pay the mortgage on bungalows or townhouses. If they didn’t own a car, they rode the bus, and if they couldn’t make fare, they walked. They memorized value menus because three meals were never enough. They saw the drug dealer’s son, strutting through the neighborhood in fresh Jordans, and described other ways that a boy can get the things he wants. They watched the draft. They pretended GMs were calling. They laughed then, but during games their stomachs clenched so tightly that they wondered if they were getting ulcers. They knew, deep down, there was a chance that the NBA would call for real.

They hid outside playgrounds during pickup runs for fear that gang members would approach with recruiting pitches. Then they hid outside gymnasiums for fear that agents and AAU coaches would do the same. I go where you go, they said, and they did, from high school to college to the pros, sometimes sharing the same roof. They still text at halftime with reminders to “fire up!” but also to thank God. They are blessed beyond belief. They drive Cadillacs. They carry Louis Vuitton bags. Their faces inspire tattoos. When they are sick, they see the best doctors, and when they are sore, they visit the finest spas. They sit in lower-bowl seats, wearing jerseys emblazoned with their last names, bouncing grandchildren on their laps. They make strategic suggestions to Gregg Popovich, and he listens.

If baseball is billed as the sport of fathers and sons, basketball is for sons and their moms. When Thunder forward Kevin Durantdelivered his tearful MVP address a year ago, he turned to his mother, Wanda Pratt. “We wasn’t supposed to be here. You made us believe. You kept us off the street. You put clothes on our backs, food on the table. When you didn’t eat, you made sure we ate. You went to sleep hungry. You sacrificed for us. You the real MVP.” Other megastars express identical sentiments on smaller platforms. “My mom tells me after games, ‘No matter what, I still love you,’” says Rockets guard James Harden. “That’s what drives me. It’s all her.”

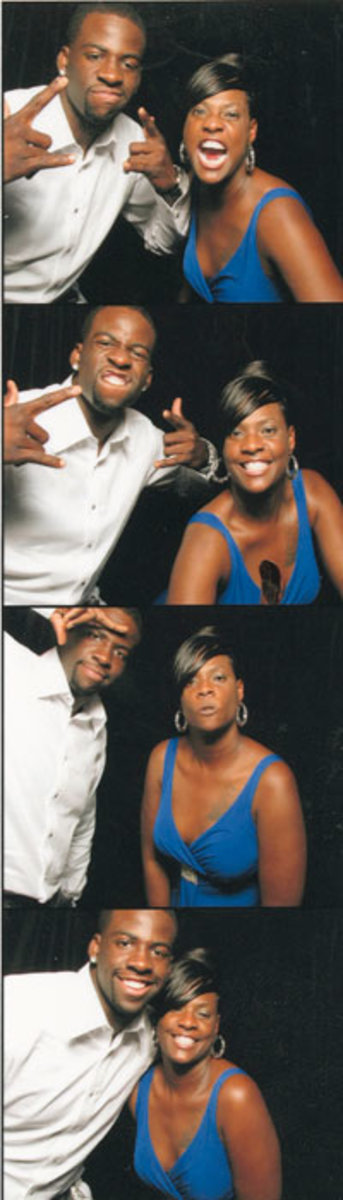

Appropriately, Mother’s Day falls during the NBA playoffs, a cause for celebration and stress. The moms break out special-occasion high heels bedazzled with rhinestone logos. They paint their nails in team colors. They construct angry tweets to critical broadcasters—then reconsider and delete. They stand and scream, occasionally at their own offspring. SI followed the first round of the postseason through five of the women who made it possible. Some won. Some lost. In a larger sense, all prevailed.

Kimberly Jordan-Williams sits in the backseat of a black Escalade heading east on I-10, Hollywood Hills rising beyond tinted windows. “Our first car was a used Cutlass Supreme, no air conditioning, and the boys fought over the front seat,” she says. “I came up with a solution. My purse got the front seat. They got the back.”

Kimberly stands 6'2" and, like her oldest son, Clippers center DeAndre Jordan, was a feared shot blocker. She played at Huston-Tillotson University in Austin, where she met Hyland Jordan, and they had four boys. But they separated when the children were young, and Kimberly moved the family into her parents’ pink-and-white bungalow in Houston’s Third Ward. She worked as a receptionist at a medical clinic and at a dentist’s office. She bummed rides from friends who owned cars. Early on, she could only afford for one of her kids to play sanctioned sports, so she chose Cory, a promising pitcher. “People tell me they knew DeAndre would be great,” Kimberly says. “I tell them, ‘No you didn’t.’ He was horrible!”

In the summer between DeAndre’s freshman and sophomore years of high school, at Christian Life Center Academy, he underwent a growth spurt so dramatic that one Sunday his mother could see over his head at church and the next she couldn’t. Suddenly, DeAndre was a prospect, waking at 4:30 a.m. to run at Hermann Park, and then going to school, where recruiters pursued him so doggedly that he once hid under the bleachers. When he was a junior, Kimberly quit her job to counsel him. I may go broke, she thought, but I will not let anyone take my child. DeAndre wound up 90 minutes away at Texas A&M.

• MORE NBA: Schedule | Grades | Awards | Playoff coverage | Finals picks

She made him fly to New York City for the 2008 draft, even though his stock was plummeting, because she remembered when he acted out all those GMs’ phone calls. She sat next to him at Madison Square Garden, fearing that his knee would rub a hole in her skirt because it never stopped shaking. When the Clippers finally picked him 35th, she told him, “This number doesn’t mean a thing.” Seven years later, DeAndre is the best rim protector in the NBA and lives at the top of a hill in Pacific Palisades. A silver Ferrari and a black Polaris sit in the driveway. A pool flanked by a hammock and a massage table look over a canyon. Rows of Nikes, like the ones the drug dealer’s son used to wear, hang in a second-story window.

“I get tears in my eyes,” Kimberly says, “because my baby did this. My baby did what I couldn’t do myself.” He bought her a house in Pearland, outside Houston, but she goes everywhere with him. Her portrait is tattooed on the inside of his left calf, next to a picture of the old bungalow. Now 26, he sends her a purse on holidays, keeping the passenger’s seat forever occupied. “The way our society is today, a lot of people don’t have fathers,” DeAndre says. “My mom is everything.”

Before Game 1 against the Spurs, Kimberly texts him to hustle and be aggressive. By the time the Escalade pulls into the players’ lot under Staples Center, she is nervous, tapping her red, white and blue fingernails against black jeans. She does not wear her number 6 jersey tee on the road—“My mouth is bad,” she explains, “and if somebody says the wrong thing about my baby, it won’t be cute”—but in Section 112 at Staples she rocks it with pride. Late in the second quarter the Spurs foul DeAndre intentionally, a popular strategy against a career 41.7% free throw shooter. “I know that little air-ball man comes out every once in a while, but this is your time,” Kimberly says. “Relax and knock ’em down.” She claps when he misses three in a row. She claps louder when he hits four of the next five.

After the Clippers win, DeAndre emerges from the locker room in a checkered black-and-white suit over a green shirt and tie. Kimberly is waiting in the tunnel with family. She has remarried, to Fred Williams, and all four of her sons are college or pro athletes. “Honey bunny!” she yells. He pecks her cheek. “What we need now,” she says, “are three more.”

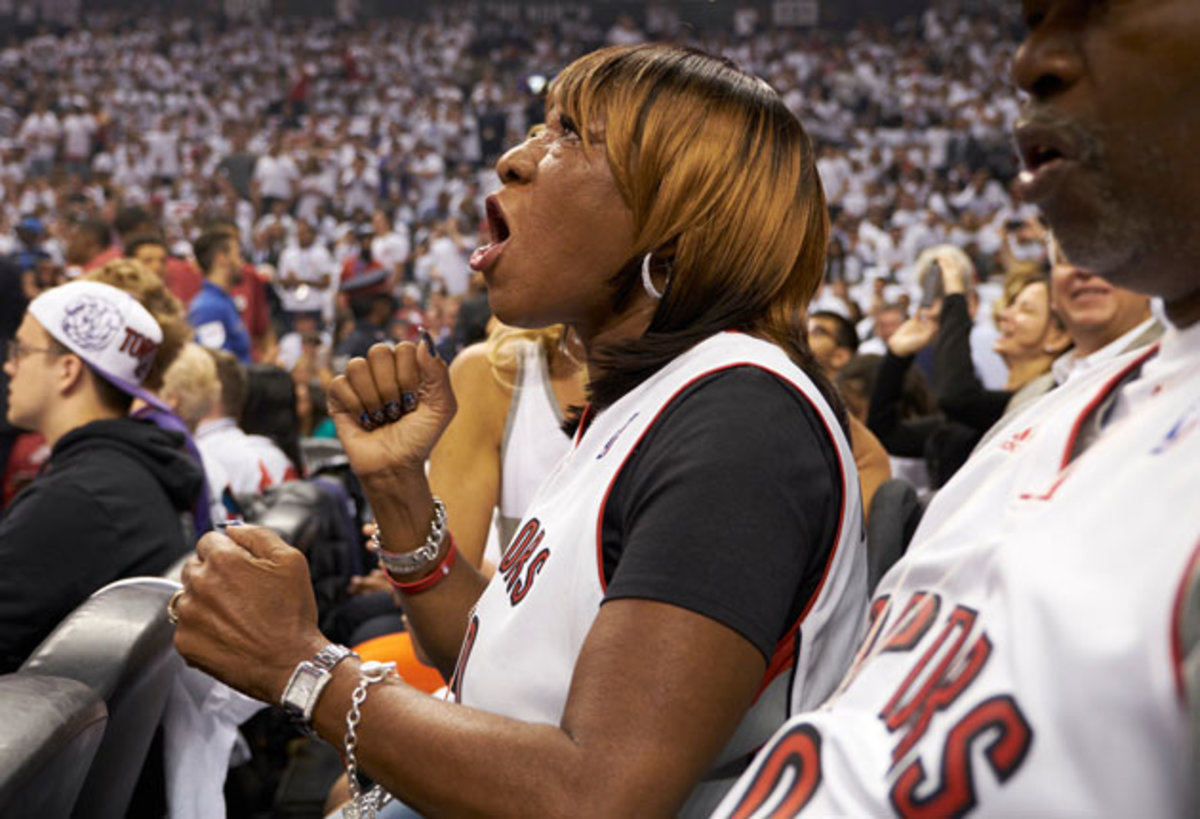

Mary Babers-Green rocks back and forth on the cream-colored sectional in her Saginaw, Mich., living room, staring down the 55-inch flat screen on the wall. In close games she kneels. At key moments she covers her eyes, peeking between her fingers. She screams at players, including her youngest son, Warriors forward Draymond Green. “Get him out of there! Put in somebody who wants to play!” She is not at Oracle Arena because she still works as a middle school campus patrol officer, and she does not allow anyone in her house because she prefers to watch alone. Her phone is her only companion. “I need Twitter because it makes me feel like I’m with the crowd,” she says. “What I write is what I’d yell in the stands.”

The NBA’s Twitter queen, who calls out everybody from Popovich to Charles Barkley, learned her hoops at Civitan Rec Center in Saginaw. “This is going to sound like a little trash talk, a little smack, but I had game,” Mary says. She could play every position, same as her 25-year-old son, but she did not respond to instruction. She was nicknamed Too Too because she was double trouble for everyone; her junior high coach cut her because she didn’t appreciate her attitude. When Mary tried out again in high school, another coach threw a ball at her—and she hurled it right back in his face. She was never more than a park player.

A decade later Mary worked at the same school as the junior high coach, and she confronted the woman one day in a campus hallway. “I still had all this anger inside of me because of what happened,” Mary says. “I was a wreck. I wanted to hurt that woman. I told her, ‘You destroyed my life because you took away the thing that meant more than life.’ I cried and she cried. After that, I decided I would not let my kids make the same mistakes I did.” Draymond was in preschool then, already playing at Civitan Rec with LaMarr Woodley, a future NFL linebacker who was five years older. “LaMarr was the big guy and Day-Day was the little guy,” Mary recalls. “They tortured him, pushed him down the court, put him in the rim and let him hang from the net. It didn’t matter. He was a spitball of fire. He always came back for more.”

The boy’s relentlessness was inherited. Mary worked two jobs—at a school and at a rehab facility—while taking classes at Davenport University and driving three hours, four times a week, to Detroit so Draymond could play AAU ball. “How did I make that work?” she wonders. “How did it happen?” She had help from her parents and from her ex-husband, Raymond Green, but for stretches she raised three kids alone in a treacherous neighborhood. “You walk out the front door and you’ve got a crackhead on one side, a prostitute on the other and mama right behind, telling you to keep straight,” Mary says. Her oldest son, Torrian, now supervises a factory. Her daughter, LaTatoya, runs a day-care center. Day-Day is the guts of the best team in the league.

Roundtable: Which NBA star is under the most pressure this postseason?

Shortly after the Warriors drafted Draymond out of Michigan State in 2012, Mary heard a noise coming from the bathroom in her home. She found an intruder, wearing a black mask and reeking of liquor, crawling through the window. He pressed a pistol to her forehead. She heard it click. “I thought I was dead,” she says. “But when I realized I wasn’t, I tried to kill that man with my hands.” Seeing that he had messed with the wrong mom, the burglar slithered back out the window. “The first person I called was Draymond,” Mary says. “He told me, ‘You get out of that house tomorrow. You move to the other side of town.’”

From her new home, she watches Game 2 against the Pelicans and fires off her usual flurry of texts. Draymond typically replies at halftime, but tonight he is silent. “Oh, come on!” Mary says. She returns to live-tweeting. She will have to wait for his response until he has finished playing 42 minutes, smothering All-Star center Anthony Davis and strong-arming the Warriors to a 2–0 lead. The next morning, Too Too is back at Thompson Middle School, guarding the campus from trouble.

Diane DeRozan is at Seventh Day Adventist Church in South Los Angeles for a funeral and the Raptors are in Washington for Game 4 against the Wizards. Diane claims to have seen—in person or on television—every game that her only child, Toronto shooting guard DeMar DeRozan, has ever played. But today she is mourning the death of her 105-year-old grandmother, Gussie Toliver, and won’t even check the score on her phone. According to Diane, Gussie is the reason DeMar is here at all.

For five years in the 1980s, Diane and Frank DeRozan tried to have a baby. But Diane had developed fibroids on her uterus, which required surgery, and afterward doctors recommended fertility treatments. Gussie, a nurse and evangelist who bore eight kids of her own, prescribed a prayer regimen instead. At 35, Diane delivered DeMar in an emergency C-section. “Every time I had a contraction, his heart rate dropped,” Diane recalls. “I told my husband, ‘Don’t worry about me. Save the boy.’”

The couple named their son after Diane’s younger brother, Lemar, who sent her Mother’s Day cards before she was ever pregnant. Lemar, a football star for Compton High, was killed in a drive-by shooting at age 20. “That’s why I have to protect you,” Diane explained to DeMar. She sat in her car while he played basketball at Wilson Park and Enterprise Middle School in Compton. She chirped, “Money!” when he let fly. She heard gang members say, “DeMar, you can’t hang with us—you’re going to the NBA.”

Diane’s sport was tennis, but when DeMar was three she won a Spalding basketball in an office raffle at the thermostat company where she worked. He dribbled the ball everywhere. He told people that Kobe Bryant was his cousin. He dunked on the mini hoops that cluttered the family’s townhouse. By the time he was 12, and jamming for real, Diane had to tote around his birth certificate.

Shortly after DeMar turned 15, he noticed mysterious spots on his mother’s hands. A year of tests followed. Doctors diagnosed lupus, a chronic illness that can cause fatigue and arthritis. “I get a lot of pain in my legs,” she says. “But they do feel better when he scores 40.” DeMar searches for more reliable remedies. He bought her two walking chairs—a contraption with four wheels and a seat—and installed a whirlpool tub in his parents’ home so she can soak her legs. He loans her his NormaTec boots, which revitalize weary limbs across the league, and encourages her to hit the spa twice a month for leg massages.

Diane does not admit when she is ailing, but DeMar can usually tell. “He’ll come over, lay down in bed with me and hold me,” she says. “He asks, ‘Mama, how you feeling? Mama, are you O.K.?’ I tell him, ‘You’re not no baby anymore; get out of my bed!’ ”

Diane and Frank were at LAX, bound for the Raptors’ playoff opener in Toronto, when they called DeMar to tell him about Gussie. “One hundred five years,” he said. “What a run.” So began a difficult week. Toronto was swept by the fifth-seeded Wizards and DeMar, the team’s leading scorer, topped 20 points only once. One of Diane’s nephews informed her during the funeral that the Raptors had been eliminated in the first round for the second straight year. “Damn,” she said, before catching herself. “Oh, Lord, forgive me.”

She remembers how DeMar used to cry after losses, how she would scold him and how she would end up crying too. “I’m an NBA mommy,” she says. “I’m going to tell him to be the man I raised, keep his head high, accept this and move forward.” She may also give her 25-year-old son a metaphor to chew on. “He could always eat sunflower seeds,” she says. “Those were easy for him. But pumpkin seeds were the hardest thing. He tried and he tried, and he could never do it—until he finally learned. I sometimes remind him of that.”

Laine Korver opens the browser on her home computer in Pella, Iowa, and sees that her son has captured the award she hardwired him to win. Laine played basketball at Montezuma High, 30 miles north, where she once scored 73 points in a game. (“Sometimes,” she says, “you just get hot.”) Working out of the high post, she averaged 41.6 as a senior, in 1975–76, heeding one basic piece of advice that she gleaned at a local clinic: “If you look at the front of the rim, you’ll hit the front of the rim. If you look at the back, you’ll hit the back. If you look at the middle, the ball will go in the hole.” She shared as much with her son Kyle when he was a boy, and even though he now plays for the Hawks and shoots according to a 20-point checklist, you can detect her influence at No. 13: See the top of the rim.

Laine and Kevin Korver met as basketball players at Division III Central College, in Pella, but raised their four sons in Paramount, Calif. The family lived across the street from Emmanuel Reform Church, where Kevin was associate pastor, and a typical weekend involved picking up trash and painting over graffiti in the troubled neighborhood. When work was done, the boys impersonated the Showtime Lakers on the court in the church parking lot, Kyle playing the role of Magic. Around his 12th birthday, the Korvers moved back to Pella and installed a Goalsetter hoop on a concrete slab in their backyard. Kyle’s range stretched beyond the slab.

Rebounding for him on concrete was easier than watching him on hardwood. “I became so nervous during games that I started to get stomach issues,” Laine says. “I had to let all that tension go and give it to the Lord, or else I was going to be a wreck.” Now she takes deep breaths in the stands. She bounces Kyle’s two-year-old daughter, Kyra, on her lap. She prays for his confidence. “There’s nothing else I can do,” she says. “He’s a husband, a father, a professional. As mothers, we raise our children, and then let them go. We aren’t in the game.”

Kyle is 34, and when he elevates from the arc, Laine does not cover her eyes or add body English. She rebounded for him again last year at Philips Arena. She saw how he makes nine of 10 threes from every location. “I expect him to hit the shot,” she says—and he does, at a higher clip than anybody in the NBA. Kids in Pella still show up at the family home and play on his Goalsetter, as if accuracy can be improved through osmosis.

But none of that has anything to do with the award. The Joe Dumars Trophy is handed out for sportsmanship, a code of ethics that Laine believes was ingrained 25 years ago on the streets of Paramount. “Basketball has been great,” she says. “It’s been foundational. But some of those other things are very heartwarming to a mother.” The day Kyle earns the honor, the Hawks vanquish the Nets in a pivotal Game 5, and Laine is asked, What means more? “The award is wonderful,” she says, “but he really wanted that win.”

Kim Robertson’s favorite Mother’s Day gifts are not the trophies or the flowers or the jewels. “They’re the cards,” she says. “Those cards are worth more to me than any amount of money.” Her only son, Spurs forward Kawhi Leonard, does not speak much. But he writes plenty: Thanks for always being there, Mom. . . . I’m lucky to have you, Mom. . . . I appreciate you.

Kawhi was 16 when his father, Mark Leonard, was shot and killed at the car wash that he owned in Compton. Kawhi’s parents were divorced and he had spent most of his childhood living with his mother in Moreno Valley, east of L.A. But Mark’s death put even more responsibility on Kim. “Tragedy can make a kid go in a different direction,” she says. “I felt like I had to watch him a little closer.” When he went to friends’ houses, she called ahead, ensuring that adults were present. And when he complained—“Mom, you’re the only one who calls”—she shot back, “Then maybe I’m the only one who cares.”

Kawhi found refuge on the court, never pausing to grieve. “You know it’s O.K. to cry,” Kim told him. He policed her as well. “Mom, you need to get on the treadmill,” he nagged, “and do cardio.” She wondered why he paid so much attention to her fitness. “It was his way of telling me, You have to take care of yourself because you need to be here,” she says. “I started exercising.” Kim ran track as a girl but she learned quickly about basketball, including the politics that surrounded her son’s chosen sport. When one AAU coach spoke with college recruiters on Kawhi’s behalf, she admonished him: “He is my child and I know what’s best.”

After two years at San Diego State, Kawhi was drafted by the Pacers and immediately traded to San Antonio, and Kim moved in with him. His bedroom was upstairs, hers down. They played Jenga. They ate enchiladas. During the Western Conference finals last May they went to dinner in Oklahoma City and bumped into Popovich. “Tell your son to be more aggressive,” the coach said.

“He needs the green light,” Kim replied.

“He has it,” Popovich said.

Spurs' early exit presents long list of off-season questions

A month later Kawhi won Finals MVP as Kim stomped her suede platform boots, sparkling with the Spurs’ rhinestone logo. “You see mothers of entertainers who don’t treat their kids like kids,” she says. “They treat them like stars because they don’t feel they can mother them and discipline them anymore. Kawhi is not a star to me. I treat him the same way I did when he was growing up.”

In January, at 23, he finally moved out. He found a smaller house, 10 minutes away, and let his mom keep the bigger one. “I was like, ‘Really? Why don’t you stay one more year?’” Kim says. “He wanted his own space. It was kind of sad. But it’s part of maturing. I came here to make sure he was O.K., and I did that.”

Kim Robertson sits on one side of Staples Center for Game 7 and Kimberly Jordan-Williams sits on the other. Laine Korver’s Hawks and Mary Babers-Green’s Warriors have already advanced. The Clippers and the Spurs are hoping to follow. In an epic culmination to an unforgettable series, L.A. ousts the defending champs when hobbled point guard Chris Paul throws in a running bank with one second left. “I’ve seen my son play a lot of games,” Jordan-Williams says afterward, wiping her eyes. “This is the best. These are tears of joy.”

DeAndre stands at the scorers’ table, among the euphoric mob, scanning Section 112. He raises his right hand when he spots the person he is looking for.

His mom.