Rewriting History: Loving basketball even after your hoop dreams collapse

It’s Valentine’s Day, 2011. Johnny Carver just threw up in the locker room and now, as he takes the court for warmups, he feels the urge coming again. But Johnny, a 6’1” guard for Shawnee Mission Northwest High School’s freshman basketball team, won’t sit out a game if he can stand.

On the first play of the night, he catches the ball on the wing. Johnny prides himself on his shooting. Typically, he wouldn’t think twice before launching this one. But typically, he can see the rim. His blood pressure is rising rapidly, and as it climbs, his vision is becoming white. With shooting out of the question, Johnny drives toward the blur where the basket should be and lays the ball off the glass. Somehow it goes in.

Playing defense is harder. He can’t tell where the ball is, or even which man he is supposed to be guarding. Shoelaces. That’s it. He remembered his guy had neon green shoelaces. Wait. Maybe they were orange. As he scans the floor, his mark scores easily. Johnny’s coach screams at him as he runs by the bench. What is wrong with you?

“I need out,” Johnny says. His coach sends a sub to the scorer’s table to check in at the next dead ball.

Johnny’s parents sit in the stands, trying to shake the feeling in their gut. “You could just see it in his eyes,” said his mother, Liza. “He was starting to weave a little bit.”

“Watching him at the time, you could tell something wasn’t right,” said his father, Brad.

Back on offense, Johnny looks around for a ref. He tries to call a timeout, but no one hears him. He takes a step towards the scorer’s table. He collapses.

*****

On a Friday in January, Johnny drove the three and a half hours from Fayetteville, Ark. to his home in Lenexa, Kan. It had been almost two years since he was forced to quit basketball. Now he was a 19-year-old freshman at the University of Arkansas, though his parents had wanted him to go to college closer to home. Being too far away would complicate things when he needed to go to the hospital. When, not if.

During his senior year of high school, when he first told them he was going to write a book, their response was measured. They wanted him to find a new outlet now that basketball was gone, but this one could only end in disappointment. They supported him, but weren’t holding their breath for its release. He was.

When he walked in, it was waiting for him in the kitchen. No wrapping, no fanfare, just sitting there on the counter. Though he didn’t know it yet, the book would get local TV stations to call him for interviews and an ESPN radio show to invite him on as a guest. The book would get him an audience with multiple NBA teams and a part time job with another. Yet it was seeing the book for the first time—his book, his name—that did the most for Johnny. The blue and gold lettering on its white cover was the most wonderful thing he had ever seen.

Ranketology: A New Way of Determining Basketball’s Greatest Player.

Written by: Johnny Carver.

He could breathe again.

*****

Brad and Liza Carver loved to show off their son. Like his father and older brother, Johnny loved basketball. On the rare occasions that he wasn’t playing or watching it, he was dreaming about it. Or studying it. In elementary school, he flipped through NBA media guides, memorizing each player’s bio. Liza would quiz him, sometimes at home, sometimes at parties. “1996, the first pick overall, drafted out of Georgetown, who was it?” she’d ask. “Allen Iverson,” he’d shoot back. Rarely did he hesitate.

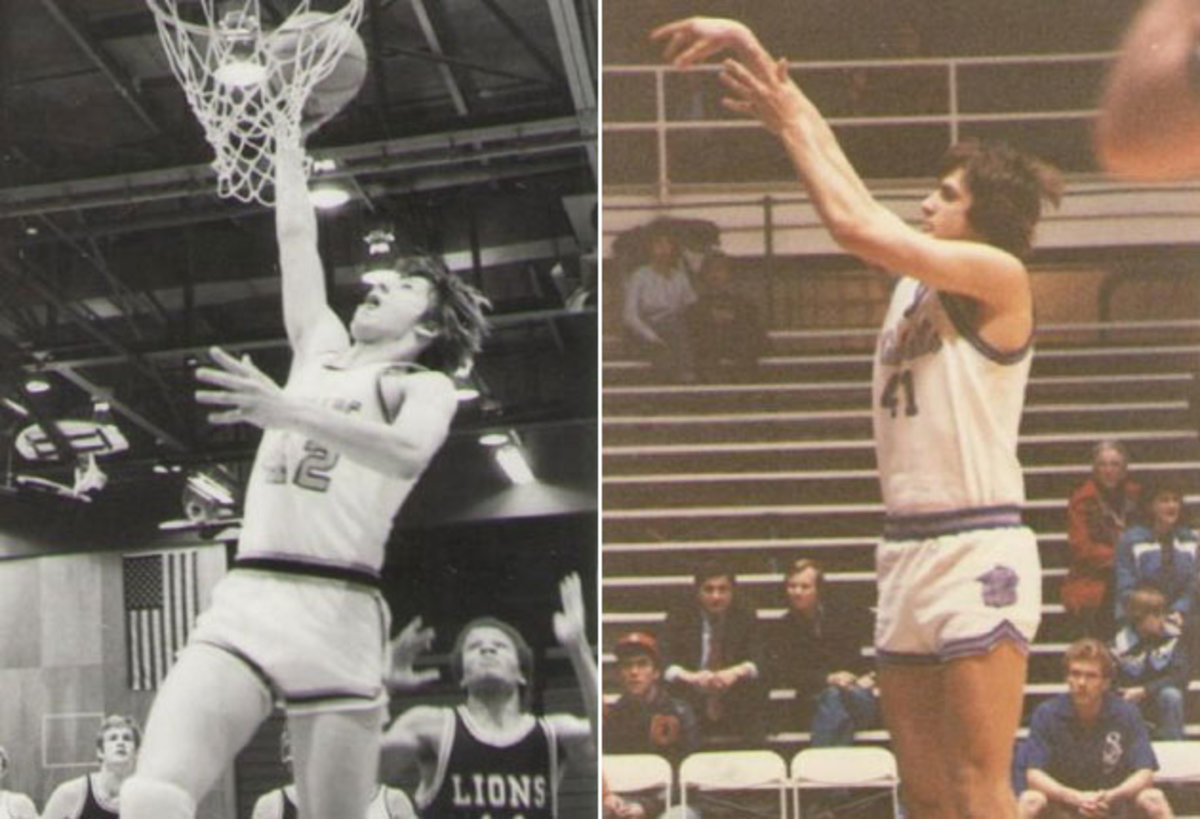

But Johnny’s true guide didn’t come with an NBA logo on the front, or with pages of numbers and facts for the addict to drink in. Instead he found his basketball compass in Brad, who in 1981 set the scoring record at Shawnee Mission Northwest before playing at Kansas State. For Shawnee, Brad was something of a local legend. For Johnny, he was nothing short of a hero. But tales of the hero’s adventures weighed heavy on his mortal sons’ shoulders.

“Growing up, knowing that that was our future and that was what we were going to be compared against and what we were going to have to try to accomplish, that definitely played a big part in our lifestyle,” said Johnny’s older brother Steve.

The brothers didn’t often compete with each other outright, but they spent most of their formative years competing with the shadow of Brad’s prolific career: 893 — their father’s scoring record at what was just a three-year high school at the time. “Steve, you’re going to break the scoring record, and Johnny is going to come and break it after you,” Brad would tease.

“I didn’t think it was a joke,” said Steve, Johnny’s elder by four years. “I had full intention of breaking it growing up. There was a lot of pressure knowing that record growing up and then actually playing in the same spot, I really had no excuse to not break it.”

So in 2010, driven by necessity, Steve did just that. The 6'8" forward finished his career with 1,115 points—the second school scoring record set by a Carver. He committed to play at Holy Cross in the fall.

Now it was the third Carver’s turn.

Johnny made the freshman team at Shawnee Mission Northwest, but no matter how far he stretched, varsity—and a shot at the family tradition—lingered just out of reach. “My freshman year, I felt like if I didn’t get moved up as a freshman like my brother did, then I had no chance of breaking that scoring record,” he said. “I felt like I had to. I felt like that was my destiny, and when it wasn’t happening for me, it felt like a failure.” Steve had played in recruiting circuits with Harrison Barnes and Kyrie Irving. Steve would beat Johnny 98 times out of 100 on their driveway court. Steve had made varsity as a freshman. Johnny was struggling to get called up to jayvee.

His teammates were faster, bigger, stronger. Johnny was 6’1” and 125 pounds, badgered by a nagging illness he couldn’t explain. In eighth grade, he had gone home sick with stomach pain. The pain had persisted, on and off, but for the most part, he learned to live with it. Things were getting worse in high school. More symptoms were materializing. The family’s primary care doctor couldn’t make sense of them. Nor could the emergency room. “You think doctors have answers to everything,” Liza said. “And they don’t necessarily.” Finally, in 2011, one did.

Johnny’s symptoms were vague. He fatigued easily and passed out occasionally. His blood pressure fluctuated often and his blood sugars were low. There was the persistent abdominal pain and, more recently, signs of internal bleeding.

Dr. Kurt Midyett, an endocrinologist at Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, was puzzled when he first met Johnny. He scheduled a barrage of tests, and their results finally gave some semblance of an answer: adrenal insufficiency. Johnny’s body wasn’t producing enough of the hormone cortisol, and as a result, it struggled to regulate his blood pressure, among other things. Dr. Midyett started Johnny on a hormone replacement to compensate for where his body was failing him, but even that didn't remedy the situation. Mystery symptoms remained.

*****

That summer, Johnny transferred. He was going to be a junior in the fall and he hadn’t gotten a tryout for the varsity squad. He had a hunch that his litany of medical issues played an unfairly large role in that. Maybe he could find hope elsewhere.

His parents bought a house in Lenexa, a city of 50,000 in the district for Olathe Northwest High School. It was only seven miles away, but leaving wasn’t easy. Johnny had been going to Shawnee Mission Northwest basketball games since he was five years old. He was a regular in their basketball camps since he was eight. And of course, Brad and Steve’s legacies were born and raised in the gym in their hometown. The Carver name meant something there. As he packed up his belongings, Johnny knew a lot of history was staying behind in Shawnee. He didn’t know if he’d grow to regret that.

A short time into the first semester at his new school, Johnny recognized a face in his sports journalism class. It was the same kid who he saw at every varsity basketball game and most of the jayvee ones. He always parked his wheelchair in the corner of the gym, his dad standing close by. In class, Johnny decided to introduce himself. The kid’s name was Jack Weafer, and he knew everything there was to know about sports. The two were fast friends.

“(Jack is) a kid with a very bright mind in a body that does not work at all,” Ann Horner says of her son. He has cerebral palsy. He also has an unquenchable thirst for all things athletic. Most days, he sits in front of his computer and combs the Internet for the rare fact or statistic he hasn’t yet found. Soon, Johnny was coming over three or four times a week after school to join the quest. The two would talk for hours about nothing but sports, mainly basketball. Jack’s dad went to West Point, which played in the Patriot League. So did Holy Cross. Jack was curious, was Johnny related to Steve Carver, a Holy Cross forward who held the scoring record at Shawnee Mission Northwest?

“He’s very engaging,” Horner said of her son. “So when he meets people, he asks pertinent questions, and he’s very interested, but it needs to be a sports subject.”

This was one Johnny knew too well.

*****

Johnny spent his junior year on jayvee, again. During the year, he had discovered another effect of the adrenal insufficiency. “That feeling you get when you get hyped up for a game?” he said. “I don’t have that. That feeling you get when you’re going down a roller coaster? I don’t have that. That makes it really difficult to have energy.”

And at the end of yet another season stuck in the mud, there was yet another diagnosis. This one was ulcerative colitis, an inflammation of the colon. It was the culprit behind the nagging abdominal pains. “When you have those two things together, your stomach hurting all the time and the inability to get motivated, that makes it really, really hard to play basketball,” he said.

There was plenty that made basketball hard for Johnny, but it wasn’t until his blood pressure spiked during one hormone treatment that basketball became dangerous. No longer were the risks limited to discomfort, nausea, fatigue, and occasionally passing out. At 17 years old, a stroke was now a legitimate concern.

“That was my first reality check that, hey, this might be a little more serious than we think,” Johnny said.

His parents had maintained that if Johnny wanted to play and could, they would let him. Now they were questioning their leniency. “I knew I shouldn’t have been playing that day,” Johnny said of the 2011 Valentine’s Day game. But he did, and the day after passing out mid-game, he was back at practice. Would he know when and where to draw the line? He was still chasing his dream, and, for once, showing drastic improvements. He had put on 30 pounds after freshman year, and with it, he found some semblance of control. Brad and Liza didn’t want to pull him away if it wasn’t necessary.

Then, junior year, he was hospitalized for 16 days. He lost 35 pounds. “Hard work pays off,” his mother would tell him. But no matter how many hours he put in the weight room, no matter how many times he showed up early or stayed late, his body’s imperfections still called the shots.

A 2013 trip to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota added another entry in Johnny’s catalog of diagnoses, and with it, a corner piece to his puzzle. This one was autonomic dysfunction, a glitch in the nervous system that leads to a body’s involuntary functions, such as the heartbeat. Because of it, his body doesn’t always recognize how much stress he is putting on it, so he fatigues easily. Any physical exertion takes an abnormal amount of effort.

Preseason for Olathe Northwest required plenty of physical exertion. Most days that summer, the team had weightlifting in the morning and camp in the afternoon. One of those mornings, Johnny lay in his bed after three sleepless nights. “I was just tired, man,” he said. “I didn’t know what to do anymore.”

Then it dawned on him. It was time to concede. “I realized, for the first time in my life, I can’t play anymore.” He went to his coach’s office that day and quit.

“I remember being crushed,” his mother said. “To see him work so hard, make the team, then give it up—that was really hard.”

But no one in the family could say they were surprised. More than anything, they were relieved. Johnny wanted to feel that way, too, but he couldn’t buy into relief completely. The anxiety and the heavy expectations were no more. Gone were the exhausting days that ended in sleepless nights. But the dream went out the door as well, and as it vanished, he lost what defined him. “It took me a long time to be able to even touch a basketball,” he said. “Nobody really seemed to understand that, but I didn’t want anything to do with playing basketball.”

His parents pushed him to get back on the court. Doctors told them that any activity would help his body. They hoped returning to the sport he loved could help his mind. “He couldn’t play basketball and with how much pain he was in, a lot of kids could get depressed,” Brad said. “That was always a concern.”

After a few months, Johnny caved. He took a ball and his shoes and set out for 68’s Inside Sports in Overland Park, alone. The past few years, he had trained on the three courts here as he prepared for tryouts. Now, in November, the gym was full of high schoolers gunning for their own rosters.

Johnny claimed a vacant rim off to the side, under the sea green outline of the overhead track. Quickly, he found he’d been sidelined too long. The ex-marksman shooter could no longer will his shots through the nylon. His legs were weak and his body exhausted. He hurt in more ways than one as he realized that everything he had worked so hard for might truly have disappeared so quickly. Soon, though, the lid came off of the rim, and for a second he let himself get excited. Then he remembered his reality. “I’m never going to make a shot that matters ever again,” he thought. “I’m never going to play in a game that matters ever again.” After 45 minutes, it was too much. He packed up and went home. Make or miss, there was no satisfaction to be found in the gym, only reminders of what he couldn’t control.

*****

When he was 11, after years of his mother’s quizzes, Johnny decided it was time to do more than talk about basketball. He wanted to write about it. So began a sixth-grader’s book chronicling the 25 best NBA players of all time. He got to the 20s before realizing the futility. His ranking was based solely on opinion, and there were plenty of those books out there, most penned by accomplished writers who had already been through puberty. He shelved the project.

In the post-basketball life he began the summer before his senior year of high school, Johnny realized his next dream. He was going to finish the book. Liza knew how passionate Johnny could be, and now that that passion was no longer directed at basketball, she pushed him to focus it somewhere concrete. But this?

“I just thought it was the craziest thing,” she said. “I thought, ‘Why would you do that? Why would you want to do that?’”

“I wanted another outlet to be successful,” Johnny said, not entirely sure what that would take. He knew no one would care about the opinions of a high school senior who wasn’t born when most of the players he was ranking retired. He’d have to find another way to gain authority.

The first 14 pages of his book explain the math behind his rankings. Johnny, Steve—who minored in statistics—and a journalist friend, Scott Chasen, spent weeks choosing 18 existing statistic categories and creating one of their own. Their Skills Efficiency statistic, developed primarily by Chasen, determines how good a player is at both rebounding and assisting, making it easier to compare two players as different as Steve Nash and Hakeem Olajuwon. In June of 2013, their formulas cut an initial list of 75 players down to the final 25 and yielded some surprising results. For starters, Michael Jordan wasn’t No. 1. Larry Bird and Magic Johnson weren't in the top 10. Now, Johnny had to back that up with his writing.

There were plenty of reasons why Johnny wouldn’t finish the writing. There was the “danger” of the act—if he stood up from his desk too quickly, he would pass out. There was the fact that he’d never written anything longer than a 10-page essay, double-spaced. Or there was the time senior year when he passed out in the middle of class and hit his head on the whiteboard while falling. He thought he was fine, but his pulse started to skyrocket. He left school in an ambulance and spent a week in the hospital.

But Johnny had waved the white flag before. He despised it. He’d do everything in his power to avoid the same fate this time. Every night in his hospital room, when he was done with his tests and the doctors were gone, he’d pull out his laptop and write.

For 10 months, this went on. Class and writing. Hospitals and writing. Friday nights and writing. Staying home sick and writing. When a profile was done, Johnny would send it to his grandfather, Bill Hudson, a published author. Hudson would edit each section and Johnny would pick up the red ink-covered pages on his way home from school. He was determined. He was holding the reins.

He was still going to Jack’s house three or four days a week. Jack’s steel trap of a mind was a fantastic resource as Johnny toiled away on the manuscript. “The thing about Jack is he’s very honest,” Johnny said. “No matter what, he’ll say what’s on his mind.” Johnny would upload the latest copy of the book to Jack’s computer and brace himself for the critique. Jack pulled no punches.

“Johnny has his own set of challenges and really he doesn’t talk about it at all,” Horner said. “I have to hope that he has drawn some inspiration from Jack. Jack is oblivious: His life has never been different at all. This is the way he’s been all of his life. I hope (Johnny) has taken some strength from that. Life is still good. You may not have all of the same abilities as everybody else, but you figure out where you can make things work.”

After everything the past few years had thrown at him, Johnny embraced a teacher like Jack by his side—someone who, on some level, understood him perfectly.

“I look at all the things that I’ve been through, and then I see what he goes through every single day and what he’s able to overcome and I’m amazed by how well he handles it,” Johnny said. “He always has a smile on his face, he’s always in a good mood and able to talk to everybody. Sometimes, when I’m going through stuff, I get really, really angry and shut people out. I did that for so long, but he’s taught me to fight through it and no matter what comes my way, I try to keep a positive attitude and include everybody in my life.”

In the summer of 2014, there was no more writing left. Johnny printed out a rough copy of the book and took it to Jack. More than 500 sources, a 40-plus page bibliography, 40-plus days spent in a hospital, 278 pages of writing, six diagnoses, two high schools, one dream cut short, one dream realized. One book.

*****

It’s been five months since the book first appeared on shelves and online. It has sold over 100 copies, more than enough for Johnny to break even. But money was never the endgame. These last few years, Johnny Carver has proved something to himself, to his family, to people he had never met.

Arkansas basketball hero Scotty Thurman publicly praised his work. He reached out to Mark Cuban, who advised him to self-publish. He sent a copy to Larry Bird, and the Pacers invited him to a game. In May, he started work with an NBA team’s analytics department, helping them prepare for the 2015 draft. His family hasn’t stopped telling him how proud they are.

In February, Johnny went back to Olathe Northwest. He wandered the halls until he found the classroom he was looking for, then stepped inside. Even after dealing with NBA legends and executives, Johnny hadn’t forgotten about the people who helped him before the rest of the world cared.

Jack wasn’t expecting him. Nor was he expecting a signed copy of a published Ranketology. He had pored through its pages dozens of times on his computer, but seeing a real hard copy was something else. Then Johnny flipped to the fifth page of the book and showed him. For Jack Weafer. After all Jack had given him—an editor, a friend, hope—these three words in the front of his book were the least he could do.

Now, the 19-year-old Johnny has his sights set slightly higher—something his father has come to expect. “He’s going to be a general manager or a janitor,” Brad said. “There’s no in-between for him.” In Johnny’s mind, the scales are leaning ever more towards the former. He’s seen what being in control can do for him. There’s no going back. He recently tweeted a picture of NBA Commissioner Adam Silver on the cover of ESPN the Magazine. “I wanna be that guy,” read his caption. He wasn’t joking.

“I’ve always had high aspirations for myself,” he said. “Everybody is looking at me like, ‘Wow, this is amazing what you’re accomplishing as a 19-year-old kid.’ And I’m looking at everything like, ‘Wow, I should be doing more.’”