Who killed Lorenzen Wright? Ex-NBA player's murder remains a mystery

Editor's note: Sports Illustrated and Fox Sports 1 collaborated on a three-part investigation looking into the 2010 murder of ex-NBA playerLorenzenWright.

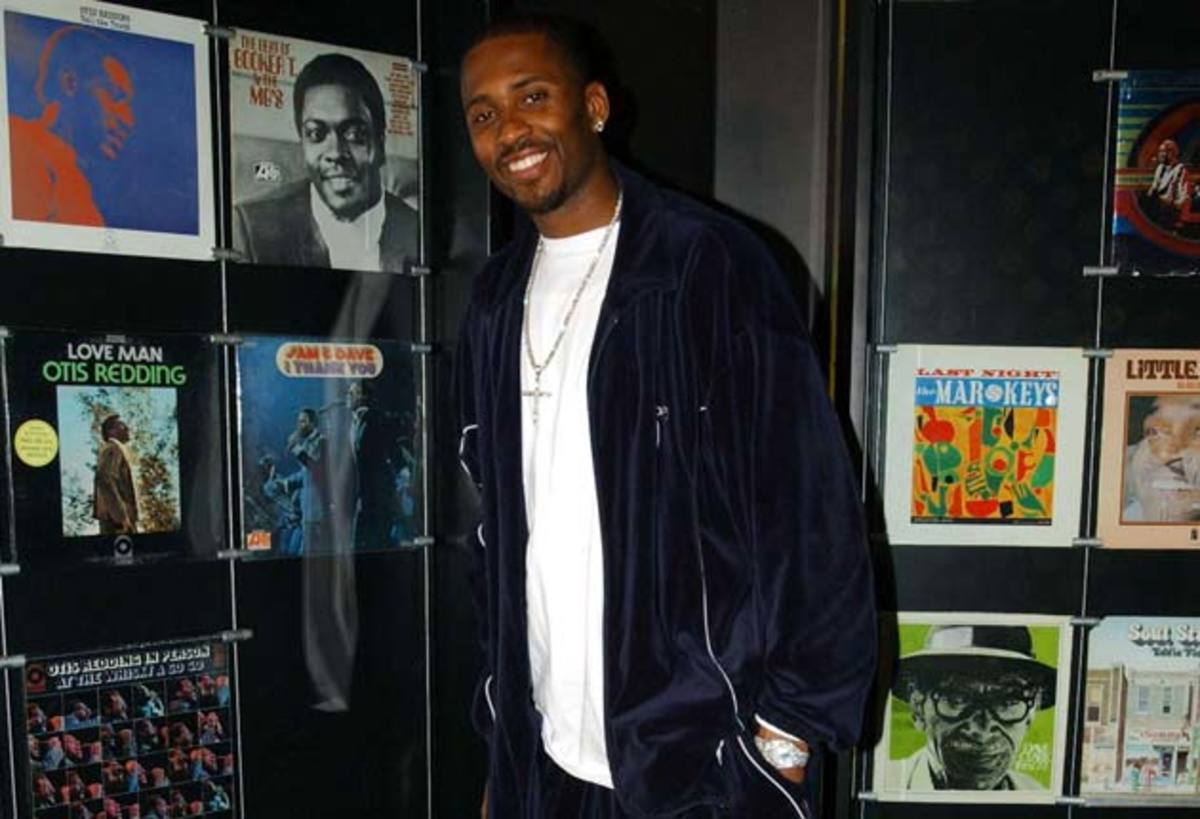

Lorenzen Wright stood nearly 7 feet tall and weighed 225 pounds, much of it extravagant muscle. His high-wattage smile was framed by a goatee—“movie star looks,” said Michael Heisley, the late owner of the Grizzlies, one of Wright’s five teams during his 13-year NBA career.

Still, Wright’s most striking feature might have been his voice, a low rumble that started deep in his gut and slowly worked its way up. With a hickory-smoked Southern drawl, the voice was straight out of a Memphis blues club. It seldom rose in volume or wavered in tempo. When you love life and it embraces you back, why yell, why panic?

If the words alone weren’t bad enough, it was Wright’s tone that made the cell-phone call to 911 so unsettling. Frantic, high-pitched, full of anguish, the voice sounded only faintly like his: Gunshot…gunshot. “Goddamn!”

Wright had recently moved to the Atlanta suburbs, but he was in Memphis on this day, as he often was. His hometown had a gravitational pull. Most of his friends lived there and most of his family, including his six kids—four sons and two daughters—then ages four to 15. This time he’d gone back to attend his sister’s baby shower.

It was July 19, 2010 and the summer was in full swing. This was at odds with Wright’s pro basketball career, which was winding down. Wright was 34 and hadn’t played an NBA game in more than a year, his body and skills eroding in tandem. The dance was down to its last few shakes. But Wright was, characteristically, going to try to wring everything he could from his career, and he had expressed vague ambitions of playing overseas, maybe in Israel. But he had recently admitted to friends that, with his basketball career expiring, he’d been feeling “kind of lost,” that his compass was failing him. And wherever he was calling from shortly after midnight on July 19, it was not where he wanted to be. That, you could tell from his voice.

He had barely spat out the word Goddamnwhen the rest of the audio kicked in: the pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-popof gunfire. At least nine shots were fired at Wright, likely coming from at least two weapons, one small-caliber, the other medium-caliber. Shots pierced Wright’s head and chest—an autopsy report would assert that “additional gunshot wounds cannot be excluded"—probably killing him in seconds.

“Hello? Hello? Can you hear me?” asked the 911 dispatcher in Germantown, Tenn. The line went dead. When the dispatcher called back, there was no answer. The location of the call could not be pinpointed, because it came from outside of the Germantown jurisdiction. Unaccountably, however, the dispatcher did not report anything to a supervisor until eight days later, an error of omission that would later hamper the police investigation—and cost the district an undisclosed sum paid to Wright’s family in a legal settlement.

Meanwhile, Deborah Marion’s maternal intuition was kicking in. Not only hadn’t she heard from her son, but her calls and texts to him were going unreturned. On July 22 she filed a missing person’s report, ominously telling police, “When y’all find him, it’s not gonna be good.” Then she waited, knowing that with each passing day, the odds of a happy outcome were diminishing.

On July 28, 10 days after the 911 call, cadaver dogs searched a remote wooded area of southeast Memphis, behind strip malls and McMansions, not far from Deborah’s home, between Germantown and Hacks Cross. Callis Cutoff, it was called, a shortcut that only locals would know, one that Wright had used when he bought a house nearby.

There police found Lorenzen Wright’s body. The frame that once took charges from Shaquille O’Neal now weighed 57 pounds and was so badly decomposed—due to rain, heat and scavenging animals—that there could be no open-casket funeral. Strangely, Wright was still wearing a gold necklace and an expensive watch.

When Deborah arrived, the police tape had already been unfurled. She had to be restrained from crossing it by a female officer. She says it’s a good thing she wasn’t wearing her running shoes. “Ain’t no way she could’ve caught me,” says Deborah, who was then in her early 50s. “She don’t know me. I’m from Mississippi, baby.”

Lorenzen Wright was one of 89 murder victims in Memphis in 2010. Though his date of death is listed when his body was found, he was almost surely killed on July 19, when that 911 call was placed. Those are the where, when and how of Wright’s slaying. But the more important questions—who and why—are unresolved. Five years after one of the most high-profile murders of a professional athlete, there is no suspect, no motive and no answer.

Memphis is a city of ghosts and spirits. They haunt Graceland, and the Lorraine Hotel, where in 1968 Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated as he stood outside room 306. They move through long-closed music studios and abandoned streetcars. They walk the cemeteries throughout town, the legacy of the city’s infamous murder rate.

The gifts and ghosts of Lamar Odom

Early on, Lorenzen Wright knew of Memphis’s spectral qualities. He was seven when his father, Herb—a mountain of a man who once had an NBA tryout with the Jazz—was shot. Herb was working for the Memphis Parks Department. On a stinking hot summer day he kicked a few mouthy kids out of the gym. One of them returned with a gun and shot Herb in the back. Herb continues to coach kids to this day, but he would never walk again.

Still, Lorenzen loved Memphis, a city which often felt more like a large town. He was from Memphis; he was of Memphis. He liked the music and the churches and the barbecues joints. “He was like the king of the city, hometown hero stuff,” says Rewis (Raw Dog) Williams, a longtime friend. “He was so proud to say, This is where I’m from.”

Lorenzen’s parents separated when Lorenzen was very young, though both parents remained active in his life. After shuttling between his mom’s home in Oxford, Miss., and his dad’s 80 miles away in Memphis, he moved to Memphis full-time as a high school senior. He started dating Sherra Robinson, whose dad, Julius, was his AAU coach. She was almost a half-decade older—and had dated the soul singer Isaac Hayes—but she and Lorenzen clicked. Though he was a McDonald’s All-American with a full slate of college scholarship offers, he committed to Memphis State (now University of Memphis). “Of course he wanted to stay local,” says Herb. After two seasons he was drafted No. 7 by the Clippers in the 1996 NBA draft, becoming a millionaire overnight.

Wright’s personality was apparent in his game. He could take over when necessary but was perfectly comfortable bringing his energy and athleticism to bear as a rebounder, shot-blocker and dirty-work warrior. “He developed what they call in Memphis the howl,” says Herb. “You know, you get a rebound and let out a howl, elbows out. Every rebound is supposed to be mine.”

When Wright was traded to the Grizzlies in June of 2001, he was like Odysseus coming home to Ithaca. “He was the face of Memphis,” says Dennis McNeil, a longtime friend and native Memphian who is now a member of the Grizzlies’ security staff. “He wasn’t as big as Penny [Anfernee Hardaway] was, but that made him kind of bigger here because people had an opportunity to see him and touch him and play with him and do all those things you couldn’t do with Penny because he was in New York or Phoenix and doing commercials.”

Wright opened a sports bar and spent a small fortune buying Grizzlies tickets for family and friends. He spread his wealth around town like a crop duster, buying homes and cars and paying for friends and relatives to go to college. He bought shoes for high school teams and underwrote a youth league. Remember the crushingly sad news report of a nine-year-old Memphis boy who lived with his mother’s corpse for a month, fearful that he’d be sent to foster care? Wright heard the story and helped set up a trust fund for the boy. “Poll people in Memphis—from his teammates in high school to the NBA—and they’ll tell you the same thing,” says Elliot Perry, a former NBA player from the city. “Ren was fantastic, this big guy with this humble spirit.”

I saw this firsthand. In 2002, I was reporting a story for SI on NBA players and their entourages. Wright’s name surfaced repeatedly. He was “the Michael Jordan of posses,” one NBA executive said, laughing. When I met Wright, he copped to it without embarrassment and eagerly introduced me to his crew, the Wright Stuff, its name emblazoned in matching tattoos.

When it’s white guys in Hollywood it’s an entourage, worthy of eight cable seasons plus a borderline unwatchable movie. Black kids in NBA circles are dismissed as a posse. But really, the two groups weren’t much different. Each member of the Wright Stuff was there for a reason. Raw Dog was Wright’s point guard at Booker T. Washington High School; as the two kids shared Taco Bell and big dreams, they vowed that if one of them blew up, he would look after the other. A decade later, Wright was still honoring his promise. The Wright Stuff’s driver was there mainly to make sure Herb, confined to a wheelchair, made it to Grizzlies home games. The cook was there to offset Wright’s partiality to the local grease-based diet. Dennis McNeil helped with security. The chief duty of one crew member was to wake Wright up at 9:15 each morning.

Wright saw it as his duty to elevate as many Memphis friends and family members as possible: “I wanted [them] to share in some of my success.”

There was plenty of it. Wright was known as an amiable teammate, a natural leader, a spindle on which his teams were wound. Wright played nearly 800 NBA games and earned more than $55 million in salary.

By the end, though, he was conforming to cliché, the numbingly familiar profile of the athlete making a mess of his post-career life, as the money and the cloud of fame dissolve in tandem. Wright spent prodigiously and with little record-keeping. By 2010 his million-dollar home in Atlanta was being repossessed, as was another residence in suburban Memphis.

He also had questionable associations. According to FBI documents, in 2008 Wright sold a 2008 Mercedes-Benz sedan and an ’07 Cadillac Escalade to Bobby Cole, a brother-in-law of Dennis McNeil. Cole was known throughout Memphis for his connection to Craig Petties, the city’s longtime drug kingpin, who had ties to Mexican cartels. (In 2009 Petties would plead guilty to 19 charges, including murder. He is serving nine concurrent life sentences in federal prison without the possibility of parole.)

When Cole was indicted for drug distribution in 2007, he offered to turn over to the DEA vehicles he had purchased with drug money. They included the Mercedes-Benz and Escalade he had purchased from Wright, which were still registered in Wright’s name. In 2012, Cole would be sentenced to eight years for trafficking millions of dollars worth of cocaine into Memphis and millions of dollars in profit back to Mexico. It’s unclear from the documents whether Wright knew of Cole’s drug trafficking.

Also in keeping with many retired athletes, Wright’s marriage disintegrated. Lorenzen and Sherra had wed young and had their rough times, not least in 2003 when their 11-month-old daughter, Sierra, died of SIDS. “I don’t think Lorenzen ever recovered from it,” Sherra says. “I dug into my spiritual grounding, and Lorenzen didn’t have that to dig into.”

They split. They reconciled and renewed their vows. They split again. In February 2010 they divorced. Wright was ordered to pay $26,000 a month in child support and maintenance. He soon fell behind.

Mookie Blaylock's downward spiral and the family he dragged with him

Sherra has since alleged that she was a victim of domestic violence and that during the marriage Lorezen was “juggling [his] women.” But she says it wasn’t the violence or the philandering that doomed the marriage. “You have to understand that as an NBA player, you’re subjected to a certain amount of theft, violence,” she says. “People see you as this bigger-than-life person, so you have to be careful who you bring into your surroundings. Lorenzen was kind of carefree in that area, and I was a little different. I possessed a spirit of discernment, so I could discern whether a person was a person who I wanted to be around or not. And when things started getting to the point where I didn’t know or I felt uncomfortable, I finally left.”

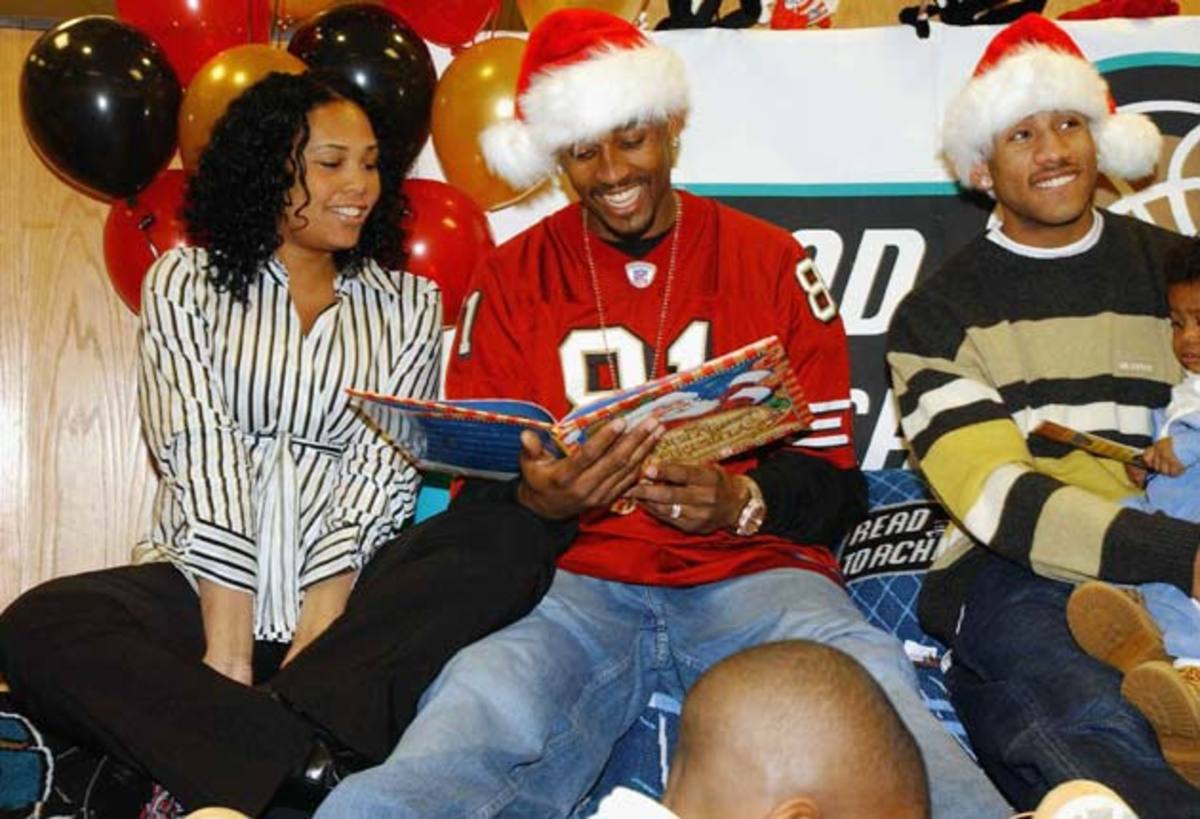

Lorenzen Wright’s memorial service, held at FedEx Forum, was an occasion. An All-Star team of NBA players attended, former teammates and childhood friends on the order of Penny Hardaway, Bonzi Wells, Zach Randolph and Damon Stoudamire. They were joined by thousands of Memphians, who were both overcome by sadness and irate that their city had done Lorenzen wrong. Heisley, then the team’s owner, spoke. So did Memphis mayor AC Wharton, who vowed that justice would be done.

If the funeral was a civic event, so was the investigation. Memphis became a city of amateur detectives out to solve the crime. One reason was Wright’s celebrity; another was personal experience. Many were well aware that the city’s homicide unit was overworked and undermanned; that too often those with information are too scared to come forward; that the circumstances in Wright’s case—the botched 911 response, the decomposed body, the remote setting where the body was found—would overwhelm the investigators. Around the city, “Who killed Ren?” was prime fodder for conversation. Geoff Calkins, a columnist for The Commercial Appeal, wrote at the time, “A Memphis tragedy has morphed into a Memphis whodunit. In four short days, we’ve gone from grieving for a favorite son to sifting through clues.”

One tidbit: Neighbors noted that on the night of July 19, Wright and a male acquaintance ignited a bonfire in the backyard fire pit of Sherra’s house in the suburb of Collierville. “I thought it was strange,” one neighbor, Patricia Coleman told reporters, “because it was like one of the hottest days of the year.”

Not surprisingly, scrutiny first centered on Sherra. When word leaked that Wright’s body had been found, hundreds of Memphians, including Hardaway, converged at the crime scene ringed by police tape. Wendy Wilson, a former personal assistant to Wright who was in the crowd, urged police to “look hard at his ex-wife.” Wilson would later claim to have voice recordings of Sherra threatening Lorenzen if she found him with another woman. (Deborah Marion said she heard the recordings, and the audio files were turned over to the Memphis police.)

Sherra was reportedly $3 million in debt, and speculation in some corners was that this gave her a financial motive in Lorenzen’s killing. Her attorney went public shooting down that theory, telling the New York Daily News that Lorenzen was “broke” at the time of his death.

The investigators, too, questioned Sherra initially, a common police practice when a spouse is murdered. She is the last known person to have seen him alive. On July 22, Sherra told Collierville police that Lorenzen had left her home on July 19 with an unknown person in an unknown vehicle.

What’s more, she said, he departed with cash and a box of drugs, and she overheard him say in a phone call that he was going to “flip something for $110,000.” He was then picked up by a driver she could not identify. She has since asserted that she never characterized the contents of the box as drugs. She now says, “That’s media. Sherra Wright didn’t say that.”

After the body was found, homicide detectives spent that weekend searching Sherra’s home, concentrating on the backyard fire pit. Sherra was also reportedly called to appear before a grand jury. She was never charged.

Another theory: Wright crossed a crime syndicate and was murdered as a result. Sherra told investigators that six weeks before her ex-husband’s disappearance, three men wearing trench coats had visited her home looking for him.

There were also the cars that Lorenzen had sold to Bobby Cole. And the fact that Wright’s jewelry and watch were intact, which suggested that this was a professional hit, not a robbery. And the fact that the body was found just a few miles from the Memphis airport; had the hired assassins simply left Wright for dead and then jumped on a plane?

Asked about a connection between Wright’s murder and a gang, Mike Ryall, deputy chief of investigative services with the Memphis Police Department, bristles. “I’m not going to comment on that right now,” he says. “We just need to withhold some information so that we can maintain some integrity about the ongoing investigation.”

However, Buddy Chapman, the former director of Memphis police force who once investigated Elvis’ death and is now executive director of Crimestoppers of Memphis and Shelby County, is happy to offer this explanation: “My personal opinion has been all along that he owed a lot of money to the wrong people and that his murder was a message: ‘If you owe us money you better pay us. It doesn’t matter who you are or how important you are. And you need to pay us the entire amount.’

“And I think quite frankly the reason we haven’t gotten any substantive tips that allowed us to look at anything was because the people that killed Lorenzen Wright probably flew in here from who knows where—Prague, Mexico City, wherever—[and] called to meet him to collect the money. He didn’t have all the money. They killed him and got on the plane and left. . . .There’s somebody out there that knows everything. And if that somebody is from Memphis, then for $21,000 [the reward being offered] we would have gotten a call.”

Wright’s friends and family rebutted this speculation quickly and adamantly. They say he might have been trying to raise cash, but consorting with known drug dealers was unthinkable to him. “I never heard anything about drug stuff, and I was with him every day,” says Rewis Williams.

“I never saw Lorenzen with a shady character,” adds Wendy Wilson. “Ever.”

Months passed, and there was no progress on the case. The heated speculation has cooled. Sure, Nancy Grace devoted a breathless segment to the case (“The Shooting Death of an NBA Star”) on her television show. In the summer of 2011 there were a few one-year anniversary stories. Deborah Marion held a one-year vigil in downtown Memphis at which her son was recalled fondly, but she was disappointed by the turnout. Even with a new lead detective assigned to the investigation, the case had clearly stalled.

A spasm of interest flared up in 2012. As part of his divorce settlement with Sherra, Lorenzen had taken out a $1 million life insurance policy to benefit the six children. But within months of collecting it, according to public records, the account had dwindled to $5.05 (Sherra contends the money was spent responsibly). Sherra reportedly spent $339,000 on a foreclosed home she placed in the children’s names. But an accounting revealed that she had spent the rest of the death benefits on everything from a $32,000 Escalade to a $11,750 trip to New York City to $69,000 in furniture for a new home.

Herb Wright launched a legal battle against Sherra to oversee his grandkids’ inheritance. She counterclaimed that Herb should be removed as executor of Lorenzen’s will. He was represented by Ruby Wharton, wife of the Memphis mayor. It was an ugly affair, covered by the local media. Each side accused the other of financial mismanagement. But when Herb and Sherra reached an undisclosed settlement, they hugged in the courtroom. “Sherra is his ex-wife, and the mother of my grandkids,” says Herb.

Sports Illustrated undertook this investigation in partnership with Fox Sports. At one point Matt Schlef, a Fox Sports producer, asked Sherra, “Did you have any part in Lorenzen’s murder?”

After a pause, she responded, “At first, I’m a wife, then I’m a mother, and then thirdly I’m an author. The law enforcement should do what’s best to find out who’s the killer.”

Schlef: “You understand obviously why I had to ask that?”

Sherra: “I do. But I’m a wife, a mother, an author, uh, I let people do what, what, what they’re good at doing and I’m just going to do what I’m good at doing. Um, they need to spend time and focus and find out what happened to him. We all need to know.”

******

The analytics and advanced stats that help sports teams evaluate players, decide whom to draft and determine how to position the defense? Big data is transforming countless other industries and endeavors, too, including city policing. In 2005, the Memphis Police Department began using predictive analytics software to try to anticipate crime and to deploy officers more efficiently. If the empirical evidence suggests that a disproportionate amount of crime is being carried out in a certain neighborhood between certain hours, resources are shifted accordingly.

It’s been a success. Still, Memphis is undeniably a rough town. In April the FBI listed it as the third-most dangerous city in America, with 124 murders last year. Even if Memphis matches the national clearance rate for murders—roughly 65%—that means that 40 or so go unsolved every year. A lot of those cases have stacked up since Wright’s death.

The status of Wright’s investigation is unclear. One member of the Memphis police force, not authorized to speak for attribution, says that the case is “as cold as cold gets.”

Deborah Marion goes further: “It’s not cold; it’s frozen.”

Not so, says Ryall: “We don’t consider it a cold case. It’s not in our cold case unit.” He says there have been leads as recently as earlier this year.

Buddy Chapman of Crimestoppers is less optimistic. “You never know what’s going to happen; somebody might say the wrong thing to somebody,” he says. Then he pauses. “I think it’s a very good possibility it won’t be solved.

In the absence of answers, family members respond in different ways. Sherra Wright, now 44, has remarried and runs a ministry, Born 2 Prosper. Last year she published a roman-a-clef titled Mr. Tell Me Anything, the tale of a philandering NBA player who moves to Memphis and marries an older woman. From the promotional material: “Despite her nurturing efforts, corruption and deceit took their stable places in his life. A breaking point is reached. She makes a life-altering decision. Does it work out for her good? Did all his lies finally catch up to him? Would he or she pay the ultimate price?” According to Bookscan, a data provider for the book industry, the novel has sold seven copies.

Sherra Wright-Robinson, as she is now called, plans to move to Houston later this year. “You want the closure,” she says. “I think I want it. I think I want to know.”

Herb Wright, too, has attempted to move forward. He says, “You can’t drop your head and feel sorry for yourself and say, ‘Why me?’ You just have to carry on. And it was really hard when that happened to Lorenzen. I, you know, I was in denial for a long time.”

When he reflects on his son, he uses variations of the word proud. But Herb prefers to do the work of grieving alone. There’s something almost Shakespearean about the Wrights’ story: a father and son both felled by firearms. The father survived; the son was less fortunate. But Herb would prefer not to venture there. “This is the first interview that I’ve given,” he says. “It will probably be the last. But I felt like five years, it’s time to say something. But it’s just not something that I like talking about. I lost a person that I cared more about than myself.”

He still lives in Memphis and still coaches youth basketball, traveling around the South. One of the walls of his home is adorned with a life-size poster of Lorenzen, looking simultaneously ferocious and approachable. “I see him every morning when I pass by, you know,” says Herb. “He will always be that age, you know, looks just like that, in our mind and hearts.”

To say that Deborah takes a different approach would be an understatement. She says that when Lorenzen died she lost more than her first child. “We were like this, you hear me?” she says, knotting her fingers. “We kinda grew up together. That was my brother and my son,” she says. “He went to his death with some of my secrets.”

Her grief is interlaced with anger and energy: She has spent the last half-decade working as an unpaid homicide investigator. Her house at the end of a middle-class cul-de-sac doubles as an evidence locker. She keeps binders filled with notes and laminated news clippings about Lorenzen’s murder. They were moved to a storage facility once she ran out of room at the house. Her lawyerlike questioning of her son’s friends and acquaintances has bruised relationships. She does not care. “I want to keep my son’s name out there, because his name came down in Memphis trash,” she says. “As long as I got blood still running warm in my body, I’m gonna be doing something. Ain’t nobody else gonna tell me when I’m tired of doing [something] for my child. Nobody, mmm mmm. I’m from Mississippi. You can’t piss in my face and tell me it’s right. I’m gonna taste that salt. They killed my child!”

Her theory in the case centers on both Sherra and organized crime. Of Sherra’s literary effort, Deborah says, “This is the book I wanna read: How I Orchestrated Getting My Ex-Husband Killed.” She believes Memphis gangs were involved, and she has vowed to avenge the killing herself. She has gone so far as to prepare a notebook thick with instructions about her funeral and burial. “I ain’t afraid of death, and I ain’t playing,” she says. “Some of my family members are scared, but I’m not.”

At one point she shared her revenge fantasy with her psychologist, who tried to dissuade Deborah and added that psychologists are duty-bound to report such fantasies to the police. Deborah stood firm. “You [didn’t] bury anything you birthed into the world,” Deborah said, “so you don’t know what I feel.”

She is not totally fearless, though. Her voice catches when she talks about her 15-year-old son, Tomonique Marion. Lorenzen’s half-brother is, undeniably, a baller. He already stands about 6' 4" and is starting to fill out his frame. Deborah says that when she watches him play, she’s transported back a quarter-century to when she was watching Lorenzen. Except this time she is wracked by ambivalence. She says, “I tell him, ‘Quit playing so hard; you don’t need to get all those rebounds, you don’t need to get all those shots; quit playing so hard.’”

Why?

“I don’t want him to be as good as his brother,” she says. “I don’t need another NBA player. I just need a child that goes to work and takes care of his wife and kids and that’s it. I don’t need another NBA player because all money is not good money. Lorenzen was an NBA player, a millionaire, knew everyone, and look what happened. He ends up dead, and no one knows a thing.”