‘I just couldn’t take the pain’: How NBA coaches deal with injuries

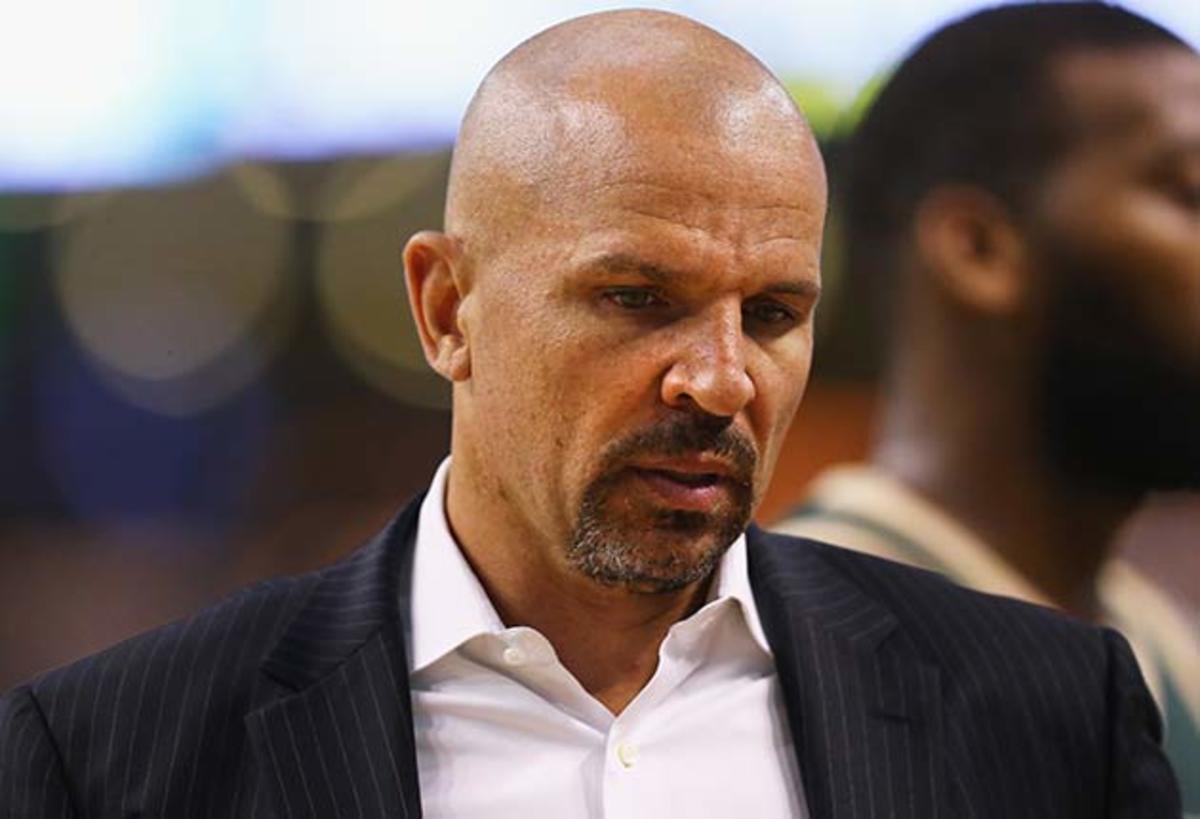

Not long after he decided to conclude his 19-year playing career, Jason Kidd faced his first post-basketball dilemma. Kidd, who had yet to coach in any capacity, much less the NBA, could either get a head start on his next profession or undergo surgery to repair the hip injury that forced him to retire.

Given his history of playing with and through injuries as a player, Kidd’s next move was hardly surprising. He became head coach of the Brooklyn Nets with only a summer to spare before he took to the sidelines. But after three seasons coaching the Nets and Bucks, Kidd could no longer ignore the pain. A player once known for his grace and speed, Kidd had no cartilage around his hip and walked with a limp. He knew it was finally time to take action.

“I just couldn’t take the pain going into this season so we had to make a decision,” Kidd said. “It’s never a good decision to have surgery, so we tried to have it as soon as possible so it didn’t affect where I would miss a lot of games. It’s been since 2011, so to have a 25-year-old hip now feels great.”

While Kidd is a rare case because he logged more than 50,000 minutes during his career, he is far from the only coach to miss time due to health reasons. The past two seasons have seen this issue broached more than usual. Hornets coach Steve Clifford faced a health scare during his first season in Charlotte and needed two stents placed in his heart before he could return in 2014–15, and the Warriors started the 2015–16 season without Steve Kerr after complications from two off-season back surgeries left him with spinal fluid leakage and severe headaches.

Kobe vs. LeBron: The definitive debate

All three coaches have returned to their teams, but easing back into action isn’t as simple as throwing on a team logo and showing up to practice. The process of returning to full health and staying there remains an ongoing process. Unlike Kidd and Kerr, Clifford did not need major surgery or rehab, yet his experience was just as dramatic, if not more. The Hornets coach was at dinner in Charlotte when he felt a shortness of breath and chest pains. He went to the emergency room immediately.

“What I was told was normally, with either strokes or heart attacks, the large majority of people don’t get a warning sign and I did,” Clifford said. “So if I wouldn’t have gotten that, the doctor told me I was probably four or five months away from a heart attack.”

Clifford’s heart problems were genetic. He did not spend extended time away from the team and did not suffer injury as the result of a long NBA career. Clifford, whose ailment was treated largely through medication, has coached his team without issue this year. Still, he did consider Kidd and Kerr's situations, and believed they must have incurred a tougher climb back.

• MORE NBA: Giannis Antetokounmpo blossoming at point for Bucks

“I would think that for both of them it’s much more difficult than it was for me,” Clifford said. “Even though mine was my heart, it was not as significant an issue as what either Steve or Jason went through. They had more significant procedures done, and I’m sure that, in terms of what they have to do just in terms of their rehabilitation to feel good, feel normal, it’s much more difficult than what I did.”

Kidd missed 17 games before returning to the Bucks full time, while Kerr sat on the sidelines as his team got off to a 24–0 start and missed more than half of the season. The situations differed, but Clifford, Kidd and Kerr all gradually transitioned back into to their jobs. No man was allowed to jump back in head first, and for people in sports, or any profession for that matter, taking time to heal and sticking to a program is key, according to the Rothman Institute's Dr. Chris Dodson.

“Obviously, if you rush things too soon then you might have complications, you can aggravate the problem, and then you can ultimately require more missed time," Dodson said. "So we always tell patients and coaches to make sure you follow instructions to a 'T' because the last thing you want is an aggravation or a complication and then now you’re missing more time than you would have had you done things the right way.”

For NBA coaches, that can mean limiting travel, scouting or practice time. In Charlotte, cardiologists told Clifford he could attend practices, shootarounds or games, but not all three. Similarly, Kidd and Kerr spent time around their teams without taking on the full burden of coaching right away.

“My patients, I have to constantly stay on their back and make sure they’re doing the right thing,” Dodson said. “Because they’re champing at the bit, so to speak, to get better but also to resume their lifestyle and resume that routine that has helped them to often times keep successful jobs and deal with things.”

With someone like Kidd, who has spent his entire life as a player or coach, that process is tough. “You miss the game,” Kidd said, “not being able to sit there and be at practice, the routine of being with the coaches and going through the game plan. It’s hard because of the excitement, the competition that you miss. Also, understanding that this is a time for your body to heal. So the more that you can save yourself from the stress, the more your body will heal. So it’s a balance.”

Once coaches return full bore, there are other delicate balances to consider, as constant travel and the grind of an 82-game season can weigh you down. Teams typically play three or four games per week, but coaches are also charged with watching their own team and studying upcoming opponents.

• MORE NBA: Steve Kerr: Warriors' ringmaster | Walton going with the flow

And while this is not always front of mind, there is also the added pressure of working in a profession with low job security. David Blatt, Derek Fisher, Kevin McHale, Lionel Hollins and Jeff Hornacek have all been fired this season alone.

“You can see all the coaches that are being fired," Kidd said. "So you got to do what’s best and you’re going to be judged based on winning and losing. So you try to do your best and hope that you’re at the top of the mountain or you find your team having success. But there’s a fine print that sometimes things don’t work out, and we all know that taking the job.”

That said, the job is not without its rewards, as Clifford is quick to point out. There are reasons coaches are always eager to return from injury or find their next job, and those benefits vary. In Kidd’s case, the chance to see young players improve on a daily basis weighs heavily. Clifford gets to watch a star like Kemba Walker take strides forward. And Kerr is allowed to return to the best basketball team on the planet.

“There are many good things about what we do and then there are some difficult things," Clifford said. "This is a profession where, if you’re looking for affirmation every day or people to tell you how good you are, it’s not the way to go. You’re paid to not just play well but win. There’s a lot that goes into that. That’s part of the challenge, but there’s just so much good to coaching in this league that in my mind it definitely outweighs the difficult part.”