Memory Trainer: Gary Vitti dishes tales on Kobe, Magic and more

Get all of Lee Jenkins's columns as soon as they’re published. Download the new Sports Illustrated app (iOS or Android) and personalize your experience by following your favorite teams and SI writers. This story originally appeared in the March 21, 2016, edition of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

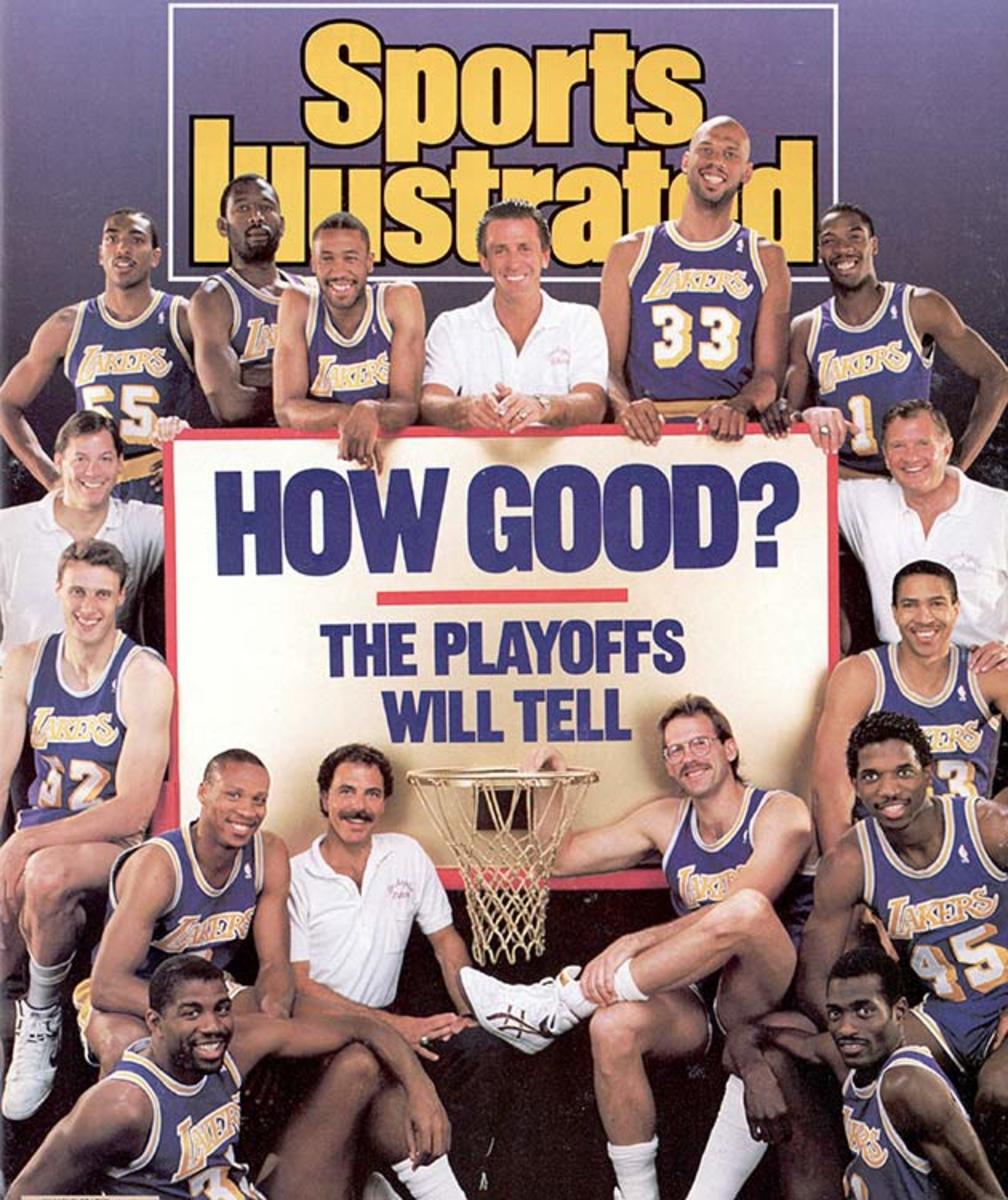

While Kobe Bryant is regaled with an unending loop of Jumbotronappreciations—Afro-era highlights and breathless interviews set to dramatic soundtracks—Gary Vitti tucks his latex gloves into his back pocket. Retiring athletic trainers do not get video tributes, even ones who logged 32 years with the Lakers, captured eight championships, kneaded Hall-of-Fame muscles, and shipped Gatorade jugs from Los Angeles to Boston because they could not trust the Celtics’ supply. But here’s what the Vitti montage might look like. Cue Green Day.

October 1984, training camp at College of the Desert outside Palm Springs, and Magic Johnson, James Worthy, and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar run the three-lane rush. They cover the court in three passes. The ball never touches the floor. “They were like deer,” Vitti recalls. “It was the first time in my life I was in awe.”

November 1984, locker room at The Forum, and Magic is still not talking to the curly-haired and mustachioed new trainer from the University of Portland. Magic mutters an unintelligible insult under his breath and Vitti shoots him a glare. Magic cracks up. He lifts Vitti off the ground. “I’m kidding with you!” he shouts.

December 1987, team bus in Washington D.C., and head coach Pat Riley wants to move shoot-around away from The Capital Centre and closer to the Lakers downtown hotel. “We can’t do that,” Vitti says. It is 1 a.m. and shoot-around is at 10. “Remove ‘can’t’ from your vocabulary,” Riley cautions. The Lakers shoot the next morning at Georgetown.

• Listen and subscribe to Open Floor Podcast on iTunes and SoundCloud

June 1989, pre-Finals boot camp at Westmont College in Santa Barbara, and Kareem strikes yoga poses while everybody else stretches. “He always did yoga and no one did yoga back then,” Vitti says. “He talked about core strength when no one talked about core strength. He used rollers for his ab work. Now everyone does that. He was ahead of his time.”

October 1991, trainer’s room at the Delta Center in Utah, and Vitti works on a third-degree sprained ankle sustained by second-year guard Tony Smith. Smith is sobbing, but Vitti keeps thinking about Magic, who has been sent home for undisclosed reasons. “What’s wrong with the guy?” Vitti wonders. “Does he have cancer or something?” He suddenly remembers the HIV test Magic took to secure a life insurance policy. He glances at Smith, still teary. “You’re going to get better,” he says. “Some people aren’t.”

October 1991, locker room at Loyola Marymount University in L.A., and Magic meets with Vitti before practice. For two weeks Vitti has kept Magic’s secret, lying to the Lakers, telling them he is suffering from the flu. “Are you okay?” Vitti asks, “because I’m not.” Magic smiles. “I’m fine,” he says. “When God gave this to me, he gave it to the right person. I’m going to do something good with it.” Vitti cries. Magic does not.

November 1991, Loyola Marymount, and Lakers general manager Jerry West is on the phone. The news is leaked. Magic is calling a press conference. “Get everybody out of the gym,” West says. “Get them in their cars. Tell them not to talk to anybody. Tell them not to listen to the radio. Whatever they have to do the rest of the day, change their plans. Be at The Forum at 2. No excuses.” Vitti evacuates the practice court. Head coach Mike Dunleavy asks what is going on. “I can’t tell you,” Vitti says. “But what you hear today will change your life.”

October 1992, Dean Smith Center at the University of North Carolina, and Magic jogs to the bench with a scratch on his forearm during an exhibition game against the Cavaliers. Vitti reaches for the gloves in his back pocket. Then he looks up. Players are staring at him. Cameras are pointed at him. He thinks of all the Lakers who have asked him whether they are in danger. “What message am I sending?” he asks himself. He dips a cotton tip applicator into a bottle of Tuf Skin and swabs around the scratch. No gloves. For the next year, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) investigates Vitti for his treatment, finally exonerating him.

Summer 1993, Paramount Studios in L.A., and Vitti is appearing in the movie “Blue Chips.” “Garr-ee Vee-tee!” a voice booms. “Greatest trainer in the worrrld!” Vitti turns around. The baritone belongs to Shaquille O’Neal.

July 2002, Port of Los Angeles Police Department, and Shaq is named second-class reserve officer. He plies his new trade on Vitti, frisking him daily, occasionally throwing him against the trainer’s room wall with enough force to require painkiller injections. Vitti bites Shaq’s hand in retaliation. They are playing, but not always. They once go two weeks without speaking, Shaq communicating via dry erase board, because Vitti refuses to excuse him from practice. “You’re too big,” Vitti tells him. “You take up too much space. You actually f--- up the game of basketball. You have to practice because there’s no one else like you.” Shaq appreciates the description. He practices.

• MORE NBA: Roundtable: Who should be the No. 1 pick in the 2016 draft?

February 2016, Staples Center, and Kobe Bryant dislocates his right middle finger against the Spurs. Vitti is transported to the 2000 Finals in Indiana, when he popped back the cuboid bone in Bryant’s left foot; the ’02 Western Conference Finals in Sacramento, when he sat at Bryant’s bedside through a brutal bout of food poisoning; the night in San Antonio last winter, when he convinced Bryant to undergo surgery on a torn rotator cuff. “He wanted to play,” Vitti marvels. He slides the finger into place and tenderly rubs Bryant’s head. He seems almost apologetic. “You can go back out there now,” he whispers.

March 2016, Lakers locker room, and Kobe wants to learn more about the Holocaust. “Did you read Anne Frank’s diary?” he asks. “Of course,” Vitti says. “Is it great?” Bryant asks. “Yeah,” Vitti says. “Is it gut-wrenching?” Bryant asks. “Yeah,” Vitti says. “Read it, but read Elie Wiesel, too.” He emails Bryant the links. In many ways, he remains the Lakers' intellectual center, introducing words of the day on a screen in the locker room. “Enigma?” Bryant sniffs. “Loquacious? Come on. Those are too easy.”

Sometimes, Vitti posts famous quotations. Always be a first-rate version of yourself and not a second-rate version of someone else. “Who said that?” Vitti quizzes. “Judy Garland,” Bryant responds. “How do you know this stuff?” Vitti mutters.

Less than a month remains for both of them. When Riley called back in ’84, Vitti wanted to be a doctor, and he was only one year shy of his PhD. “You can do everything you wanted to do,” Riley told him, “only now you can do it with the greatest athletes in the world.” Of course, Vitti does not regret taking the job, but he does regret missing the degree. He will remain with the Lakers as a consultant for the next two years but he also hopes to resume classes.

When Vitti came to L.A., NBA teams were smaller, and Riley shared his equation for success: 12+2+1. Twelve players. Two coaches. One trainer. Everybody else, from family to friends to front-office executives, Riles termed “a peripheral opponent.”

From Showtime to Closing Time, Gary Vitti was the 1.