Guarding Steph: The only man who can lock down Curry

Get all of Chris Ballard's columns as soon as they’re published. Download the new Sports Illustrated app (iOS or Android) and personalize your experience by following your favorite teams and SI writers.

OAKLAND, Calif. — The call came from the Chief of Police on the afternoon of Dec. 1, 1997: Report to the Oakland Marriott at 1001 Broadway for a 415. Code for disturbing the peace.

The address didn’t strike Officer Ralph Walker, a 20–year veteran, as unusual—the Marriott is downtown, in a heavily-trafficked area. But the specific location did: The fifth floor. The new practice facility of the Golden State Warriors.

Walker wasn’t summoned because of his background, but it didn’t hurt. He was, after all, the only former NBA draft pick on the force. And, at 44, he still looked like he could play. Six-foot-three and muscular, he retained much of the athleticism that once earned him the nickname “Rocket,” on account of his 41" vertical leap.

Sirens blaring, Walker and his partner, Terrance West, sped toward the Marriott. Upon arriving, they heard a strange tale. Latrell Sprewell choked head coach P.J. Carlesimo, then returned 20 minutes later and took a swing at him. The NBA security rep on hand, a former FBI agent, had to accompany Carlesimo home. Walker and West were tasked with guarding the doors to the practice facility, in the event Sprewell tried to come back, alone or with friends.

The two stayed until the end of their shift that night, but Sprewell never returned (literally and figuratively; the Warriors ended up voiding his contract). Still, standing in the winter sun that afternoon, watching Warriors staffers come and go, Walker was inspired. He’d spent two decades on the force. He was due to retire soon, and could take a new job. Perhaps this was serendipitous. Perhaps he’d found a way to stay around the game he’d loved his whole life.

*****

“COMING OUT!”

It’s just after 6 p.m. on a March night in 2016, and Walker, now the manager of Warriors security, is clearing the tunnel in Oracle Arena that leads from the Golden State locker room to the court. Steph Curry is heading out to warm up and Walker needs to make sure no one gets in his way—not a preoccupied reporter or a Lagunitas–toting luxury–boxer passing through.

A few moments later, when Curry emerges, Walker follows. If needed, he could keep pace—part of his job is staying in shape and, at 63, Walker watches his diet and knocks out 150 crunches daily, as well as his age in pushups and situps, never knowing when he’ll be called to action. Like the time at All-Star Weekend in Toronto, when the crowd to see Curry at a mall was so large and exuberant—nearly 2,000 strong—that it overran the hired security and Walker had to lead Steph on a mad dash through the aisles of a clothing store, running low—“almost like I’m doing a raid on a house” says Walker—to escape without being mobbed (apparently, Steph found it all very exciting).

• MORE NBA: Inside a Warriors practice: Laughs, lessons and basketball

Now, as Curry lofts 40-footers on the court, Walker stands nearby in a blue suit, arms folded, watching the perimeter. In this, his 11th year—the first six as an NBA security rep for the team, the last five with the Warriors exclusively—he’s seen a lot, from the team’s darkest days to its current, historic run. He is, in some respects, the team’s fixer. Few men have spent more time sober inside night clubs at 2 a.m. By now, he knows all the tricks. How to spot the “snipers,” as he calls the autograph hounds who pretend to be hotel guests to ambush players (“Watch the facial expression,” says Walker, “they’re focused, always hopeful”); how to run name checks on players quarterly to ensure traffic tickets aren’t forgotten; and how to use his size and bearing, rather than force, to disarm a situation. With his short black hair, thin goatee and strong chin, his bearing is almost regal, and he’s often mistaken for an assistant coach.

Twenty minutes later, Curry jogs off the court, taking the first Sharpie proffered to sign roughly a dozen autographs, then handing it to Walker to return to its owner. The point guard is one of two Warriors that Walker knows will always sign, along with Klay Thompson. “Even if we pull into a city at 2 a.m. on the road, Steph and Klay gonna sign.”

Listen to the Open Floor Podcast and subscribe on iTunes and SoundCloud

Over the last two seasons, Walker has likely spent as much time with Curry as anyone outside the star’s family. Last year, at the urging of GM Bob Myers, the team hired a second security rep—Walker’s old partner, West—so that Walker could focus on Steph. He now accompanies Curry virtually everywhere he goes when on the road. If Steph wants to go to Starbucks, Walker goes with him. They sleep on the same floor at hotels. They see the same movies. When Madame Tussauds unveiled a statue of Curry recently, Warriors PR director Raymond Ridder joked that it, “Should come with a wax Ralph next to it.” So tight is their bond that when Curry won the MVP award last season, he spent nearly a minute of his speech talking about Walker—a touching moment and, to the best of anyone’s recollection, the first time an MVP has done such a thing. Says Walker: “Other security guys tell me that put us on the map. That they wish their guys would do that.”

Ask people around the Warriors about Walker and you’ll hear variations on a theme. Calm. Collected. Gets along with everybody. Has your back. “He takes everything he does seriously,” says Draymond Green. “Crosses his T’s and dots his I’s. Always stays ahead of the curve.” Myers calls Walker, “Impossible not to like.” Says Myers, “If you don’t like Ralph, I think you’ve got real problems. He’s someone you always want in the room. He’s a huge part of what makes us a special place. I mean, I know Steph values him probably higher than me.” Backup center Marreese Speights calls Walker, “A good old head,” saying, “We all look up to him.”

We all look up to him. That’s not something you usually hear an NBA player say about a security guard. But then again, Walker has to be the only security guard who once had his own Reebok commercial.

*****

He played the middle at 6’3”. Anything that a 7-footer or 6’9” could do, he could do, just a little bit better….

The year was 1987 and Reebok was running a Streetball Legends campaign. If you’re of that era, perhaps you remember. A guy talking to his buddies about a player named Lamar Mundane: “His shots would hit bottom so often, people started to call him ‘Money.’ Cause when he shot, it's like putting money in the bank. I mean, you could bet on it. I seen him come down on the break, pull up, and then spin, take a 15-footer. Everybody on the side be hollerin', "Layup!"”

Chances are, however, you didn’t hear the other ads in the series, as some appeared only on local radio. One described a, “guy who had so much talent it was amazing,” that 6’3” player who could do what a seven-footer could? Ralph "the Rocket" Walker. As the ad went, Walker could “Catch an alley-oop and throw it down backwards. But, the fanciest dunk I seen Ralph do was when he went up with two hands, hit the ball two times on the right side of the backboard and dunked backwards on the left side. That takes HANG-time."

The commercials celebrated a golden era in Chicago playground hoops, when Mundane, Walker and their West Side crew headed from park to park in the mid-70s, taking on all comers. Lamar was the shooter. Walker was the undersized center. And a wiry guard named Danny Crawford was the team’s defensive specialist (Crawford, now an NBA ref was, “the baddest defender around,” according to Walker). Calling their team "Zebos," a name chosen because “it had an African tone to it,” the team ran on offense and pressed so relentlessly that the boys called their defense “the migraine.” One year, they won the high school division of a local tournament, then doubled down and took the men’s division in another.

• MORE NBA: Warriors leaning to survive even when Steph Curry sits

For Walker, Chicago was an adopted hometown. As a boy, his parents moved from Arkansas to Detroit, looking for work, before landing on the West Side, where his dad found a job as a valet at a garage and his mother worked at a magazine factory. At Orr High, young Ralph played center. College coaches called—including Indiana's Bobby Knight, according to Walker—but Walker struggled academically and ended up at Henderson Community College in Athens, Texas (now Trinity Valley Junior College). After two years, he enrolled at St. Mary’s, in the Bay Area, choosing it over Arkansas and Missouri.

Walker ended up playing nearly every position—jumping center, slashing on offense, guarding the opponent’s best player and bringing the ball up against the press. He excelled, averaging over 20 points and eight rebounds as a senior. The Gaels did not, finishing 3–23. Whereas once he’d dreamed of playing for the Warriors, now he feared he’d go undrafted.

Chosen in the fifth round by Phoenix, Walker headed to summer league with the other Suns draftees, including top pick Ron Lee. And that’s when Walker learned a hard lesson. “I'm tearing Ron Lee's butt up every day in practice,” says Walker. “Thinking, in my mind, as a younger player, that that's all that should matter. Not even knowing that they'd invested all of this time in making this guy their No. 1 pick. I'm just a guy that they just probably said, ‘Hey, we got to fill our tent.’” Today, Walker sees fringe players arrive on the Warriors and knows what’s in store. “That's the sad thing I see,” he says. “I know that they don't really have a shot to make our team, because our team is already in place. And I have to kind of counsel them in a way to say 'Hey man, do you have a plan B?'"

Cut by the Suns, Walker returned to Chicago and got a job at a Sears distribution center. Then, to his surprise, the Seattle Seahawks called. Maybe you’ve got the athleticism that your skills will transfer, the team said. So, as he recounts, he headed out west but was pitted against a young talent named Steve Largent at wide receiver. The team moved him to DB but he didn’t make it there either. He was waived before the first preseason game.

Out of sports, Walker called his old St. Mary’s coach, Frank La Porte, and landed a job as campus security. Not long after, he joined the Oakland Police Department. Walker began on the relief squad, then moved into foot patrol, working the corners downtown. He adopted a community policing approach, before the term was fashionable. Current Deputy Chief of Police Oliver Cunningham, who considers Walker a mentor, recalls being amazed at his approach. “He seemed to be able to relate to anybody, whether you were a convict or an affluent person in the Oakland hills or you were homeless. He had this calm demeanor about him. He’d talk to the marijuana dealers—‘Hey guys, how ya doing, I know you’re out here and what you’re doing. Stay out of trouble and keep that stuff off the block.’ Then a 65–year–old adult male in a wheelchair, smells bad, and he looks homeless. And Ralph would stop and say, ‘How you doing today?’ He just knew everybody. You’re kind of in awe. He reminded me of the movie, Colors. I felt like he was Robert Duvall and I was Sean Penn.”

Windy City smooth. That’s how West describes his former partner’s temperament. Cunningham describes Walker as, “policing with his mouth”—an officer who could bust a guy for weed and, three days later, when the guy was back on the street, he’d see Ralph and say, “What’s up Sky Walker” (his nickname around Oakland). Says Cunningham: “That’s what we miss nowadays in law enforcement. We miss the Ralphs.”

In 1990, Walker became program coordinator for the Police Activities League. Operating out of a worn-out middle school gym in Sobrante Park, perhaps the roughest neighborhood in East Oakland, he devised a slogan: FILLING PLAYGROUND, NOT PRISONS. Working with boys age 8–18, Walker coached sports, played ping-pong with kids after school and showed the boys, some of whom had never even ridden a BART train, that it was a wide world. He took them fishing and camped at Lake Temescal, even though Walker himself hated camping. When local gang members showed up, trying to exert authority, Walker relied on the same approach he’d employed on the corners. One time, memorably, a young man challenged him to a fight. Walker accepted and told him to go outside, where he’d get what was coming to him. Then, once the boy was outside, he locked the gym doors from the inside.

• MORE NBA: Almost a champ: Jermaine O'Neal on leaving the Warriors

It was during his time at PAL that Walker met an inquisitive 13–year–old kid named Marcus Thompson, who he coached in basketball. Thompson wasn’t much of an athlete, but Walker didn’t care. There was more to life than sports, he told the boy.

After eight years, Walker returned to foot patrol. Meanwhile, he led the Oakland team to multiple Police Olympics titles, first in 5–on–5 hoops and later 3–on–3. His stories about his time on the force could fill a book: the time he climbed into a second–floor window to investigate a shooting and became part of a hostage situation; chasing a suspect four blocks in the rain after a bank heist and apprehending him, a feat that made the Chronicle. And of course the Sprewell incident, where he first got the idea to apply for a job with the NBA (according to Walker and West, it was former Warriors legend Al Attles who finally stopped Sprewell that day and made him leave the gym. Says West of Attles: “Nobody messes with the Destroyer. That’s a highly-respected and feared man.”)

Finally, in 2003, at age 50 and in line for a good pension, Walker retired from the Oakland PD, having received over 50 letters of appreciation from the community and several departmental commendations. In 2005, he began as the NBA security rep at Oracle. Six years later, when the Warriors brought him on, his hiring was reported on the website of the San Jose Mercury News. The story was by a young reporter named Marcus Thompson, now the Warriors beat writer, and it was titled, “A Special Thanks to Ralph ‘The Rocket.’”

“Usually, I wouldn’t write about a hiring that doesn’t impact the product on the court,” wrote Thompson. “But in this case, my journalistic training … will take a backseat to my personal prerogative.” Thompson described how Walker inspired him, and taught him conflict resolution skills. “Ralph was the first person, outside of my parents and family, who valued me despite my lack of athletic process and for my character and effort,” wrote Thompson. “He valued us kids who had a good head on our shoulders. That means a lot to an impoverished teenager trying to figure out who he is and trying his best to do the right things. I realize that now more than ever.”

Now the two work in the same building most days—mentor and mentee, reunited—and are, in some respects, co-chroniclers of this singular Warriors team. Thompson is in the process of writing a book. And Walker, well, as Thompson says, “Nobody knows more than Ralph.”

*****

“Sometimes you have the talent but the chemistry isn’t there,” says Walker. “We talking about the Matt Barnes days.”

It’s a recent Warriors game and Walker and West are standing guard outside the locker room, discussing the challenges of the job. Many of which, if you can believe it, involved the team from the “We Believe” era, when Barnes, Stephen Jackson and Baron Davis were around.

Walker’s strategy with players like Barnes was to be “in their ear”. Says Walker: “Telling him about the fines he's gonna get, saying, ‘First of all, it doesn't look well for you, it doesn't look well for the brand.’ Matt was one of those guys. I was gonna say, he was worse than Draymond [Green]. Draymond is the glue of our team and he's got that fire in him. Matt is the kind of guy that gives you that fire, but I don't think that he's even that tough. It's almost like a drunkenness. He can be like the drunk that gets courage from drinking. He's got that reputation now that he just feels like he's got to hang onto it. So he tries to intimidate. I'm trying to recall if I've ever actually seen him fight. I just think that now because he has that rep, and he tries to show that he's not afraid, he has to continue to maintain that image.”

At the time, the players tried to fly under the radar. “Most of the stuff that those guys were doing was being well–protected by staff,” says Walker. “So I said look, I'm not trying to get into anybody's business, I'm just trying to make sure they're doing the right thing, they're getting their driver's license on time, they're not driving with warrants and things like that. But nobody was willing to really trying to assist us on those kind of matters. They were really hesitant about giving us any information. I said 'OK, fine.' So eventually, Joe Lacob bought the team. And when Joe Lacob bought the team, they kind of got rid of all the old executive staff. And it appeared they were looking for more quality character-type players than what they had had before. I think some teams in the old days would just get guys. Even if guys were good, they were just dealing with the headaches with these guys, they were taking them.

"I think Joe Lacob decided, you know what? We're gonna try to get more quality guys. And I remember talking to Bob Myers, and I go, "Bob, you got a lot of good guys. You try to get rid of me?" And he said, "No, we're just trying to make sure they stay good."

• MORE NBA: Golden Touch: How to shoot like Steph Curry (or at least try...)

As a result, the challenges these days are different. Sometimes, Walker ends up being a therapist of sorts, as with Marreese Speights, with whom Walker became close with after Speights got a DUI last year. Walker drove him around, the two bonding over girls and music. Now, Speights takes Walker and West out to dinner on the road. Says Walker: “He’ll get a chance to vent that he thought he hit three shots in a row, but then they pulled him out the game. And I go, "Well Mo, you hit three shots, but you wasn't playing no defense." Or, "Rebounds were bouncing all over your head, you wasn't grabbing a rebound."

Walker endeavors to provide big picture perspective. He tells Speights: “It’s not just shots, it’s everything. You know, if you're loafing around in practice, they may go, 'Ehh, he's not motivated today, we'll play somebody else that we've been wanting to give some other minutes to.' And then he's sitting there wondering whether or not he should have gotten more minutes. And you just try to tell him, ‘Just be ready for your time to happen. When your time comes just be ready to go.’” (Speights in turn says he appreciates that Walker, “has no motive. He loves looking out for the players.” Then, unable to help himself, he adds, “And he love getting killed in Spades on the road!”)

West describes his and Walker’s role as “providing counsel.” “We don’t tell them what to do,” he says. “Instead it’s ‘Here’s something to think about,’ or ‘I might not do that.’ Ralph and I are around everybody in the organization. We see things that one individual might not see. They might have one piece of the puzzle. We see it all.”

Curry is a unique situation, however. Asked if he’s ever seen Steph lose his confidence, Walker says, “No, no, no,” adding, “he’s a very calm, very bright young man.” With Steph, it’s Walker who worries. “Sometimes I feel like I'm kind of stepping on Steph's toes,” says Walker over lunch at the Marriott after shootaround one day. “Because I want him to still have his freedom and his privacy. But he really can't hardly go anywhere.” Walker tells a story of the old Steph, the one, “Who’ll do stuff like, it's Halloween, and he and Ayesha are sitting around the house, they're kind of bored, and they'll say, "You know what? Let's go out to Stoneridge Mall and put on costumes, and see how people react. See, cause they wanna still be kids and have fun. But their lifestyle has kinda hindered them a little bit. You know, you can't go anywhere. But those are the types of little crazy things that Ayesha would do growing up. And they probably miss ‘em. They probably miss ‘em.”

Because Curry is Curry, he always invites Walker to sit with him when he eats, but Walker declines. If he sits with Curry, he can’t see the exit routes or monitor who comes and goes. So Walker instead takes a nearby table between Curry and the door. He tries to remain discreet, eschewing the Secret Service approach of some NBA reps, who insist on taking the window seat at diners, to be between players and a potential bullet. Says Walker: “Players don’t want to be treated like the president.”

Much of the job is creating boundaries. When the Warriors arrived in Los Angeles to play the Lakers earlier this month, over 100 fans waited outside the hotel. After helping players navigate the entrance, Walker accompanied Curry to a shoot for Under Armour in the evening, then fielded a call from Steph after the team dinner. He wanted to go see Deadpool. At midnight. So Walker chaperoned Curry, along with friends and family, to the 12:30 a.m. showing at a local theater, returning to the hotel by 3 a.m. It was a mundane night compared to some. After all, he’s available to players at any hour. His job is to make sure everyone gets home safe. That may mean being the designated driver, or breaking up a potential altercation or, as West puts it of his and Walker’s job, “We’re the players’ conscience when it’s not quite functioning.” Walker in particular has stories—of opposing players standing outside clubs, demeaning women and being so drunk they can’t recall the number for the limo company—but they are not ones he can share, at least not publicly.

• MORE NBA: Golden Season: Chronicling the Warriors' pursuit of history

In Curry’s case, escape is often the goal. Like when Curry decided on a whim to play in the San Francisco Pro-Am, dropping 43 points, and gathering thousands of fans by the second half, forcing Walker to enlist Curry’s teammates as impromptu bodyguards. Or that mob scene in Toronto, where Ayesha ended up getting “kind of hit in the eye,” as people reached out. Occasionally, it turns darker. “There’ve been some threats against him, people saying [online] that if Steph hits another three point shot, they’re gonna kill him,” says Walker. “The NBA has a cyber–surveillance network and they get stuff all time. People will tweet that they’re going to come out on the court and slash Steph.” (Walker says most are just online idiots and he has yet to deem any an “actual threat”).

Road trips are the most intense. When the Warriors pulled into Milwaukee at 3 a.m. earlier this season, after playing an overtime game in Boston, Walker was shocked to see a horde of fans—well, autograph collectors—waiting, some with young kids in tow. He wasn’t the only one. “Andrew Bogut yelled out, ‘Man, you should be arrested for child abuse!’”

To account for the increased crowds, the Warriors have hired additional outside security on the road to occupy the team floors, lest the collectors walk the halls, looking to snatch stray gear. Meanwhile, Walker exchanges business cards with hotel security directors, hoping to keep a low profile. “If there is an issue with any of our players, or any of our rooms, notify me first,” he tells them. “Let me address it first before you decide to call any other law enforcement people to try to deal with it.” This means it falls on Walker to tell players to keep it down, just as he’s the one who has to rouse late-sleepers when they miss the bus or accompany young guys who have a sudden urge to go party in the wee hours.

• MORE NBA: On the road with the Warriors: Rick Reilly's cover story

Some nights Walker is out til 4 a.m., then up again at 8 a.m. He’s learned to take snacks from the plane and keep them in his backpack, as he never knows when he’ll be stuck somewhere for hours, whether it’s his room or a club. He spends so much of his day standing, or moving, that he wears rubber-soled shoes; the last thing you want to do is have to run on the court and then slip because of your dress shoes. “I’m always working,” he says. “My schedule don’t matter.”

Now, as the countdown to 73 begins in earnest, he talks about the future by phone from a hotel in Utah, on the morning before Wednesday's overtime win against the Jazz. The team got in at 2:30 a.m. the night before, after beating the Wizards at home. The players are still sleeping. He’s readying to secure the breakfast area. As he talks, West texts him, telling him there is already, “a family of snipers in the lobby but otherwise all clear.”

Walker knows it’s only going to get crazier in the weeks to come. The final push. The playoffs. The media and fan crush. Maybe another trip to the Finals (Only hours later, that night, a railing will collapse in Utah as fans try to get Curry to sign autographs; "I'm glad I was there to keep him safe," Walker texts the next morning). He’s ready. He does his push-ups. He runs sprints with Speights and Festus Ezeli on occasion, both to stay in shape and to motivate the big men. “Because you can’t let the old guy beat you," he says.

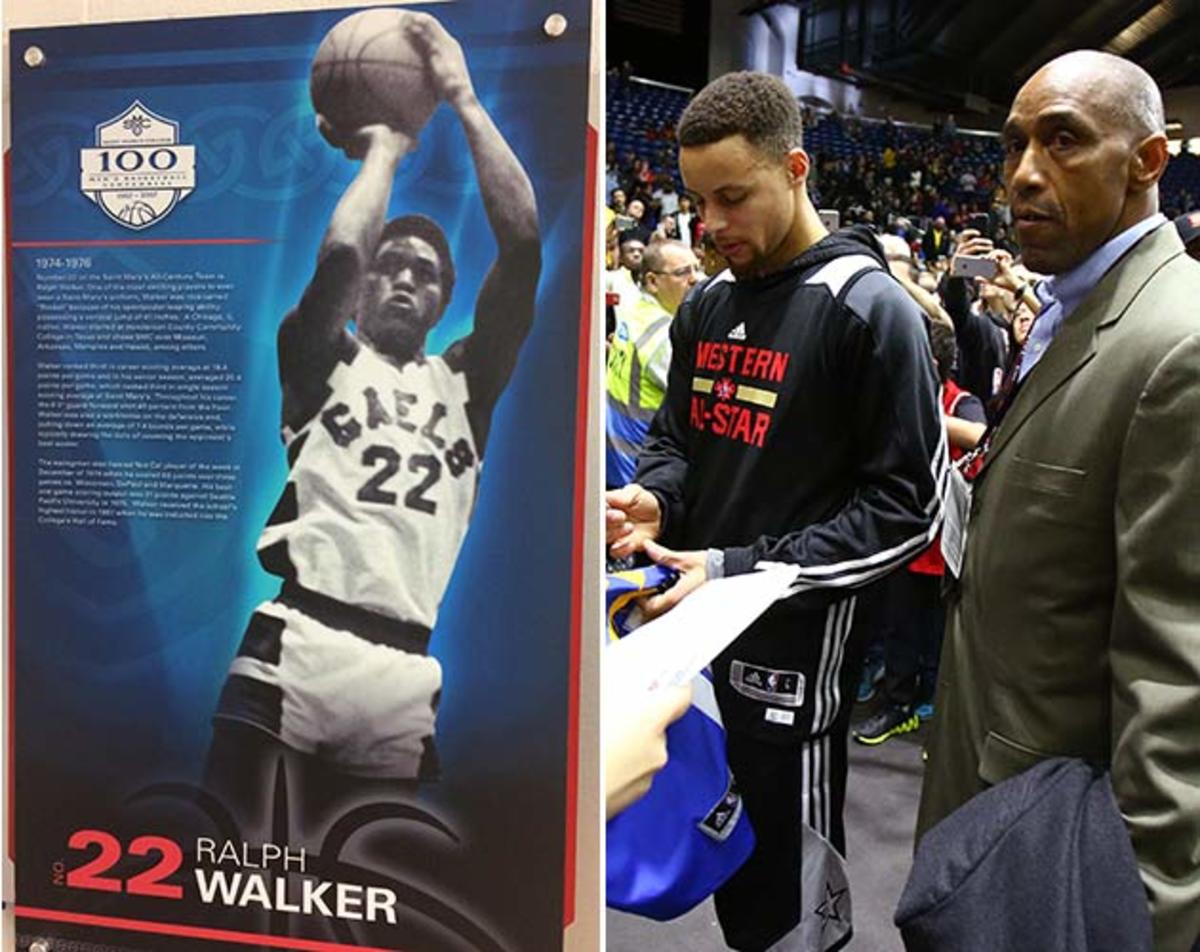

But he also can’t do this forever. It’s become nearly a year-round job—summer camps with Curry, attending sponsor commitments with other players, checking on someone’s house if they’re worried it’s not secure. Someday, maybe soon, he’ll call it quits. His garage has been waiting on him for two years. His own father died of a heart attack at 44 and he wants to be able to sit down and have an adult conversation and watch a game with his three sons, who are 31, 28 and 21 (divorced, he also has a daughter who is 13). Maybe he’ll swing back by St. Mary’s, where a plaque hangs in the hallway, a photo of him in mid-jumper, from when he was named to the school’s All-Century team. Maybe he’ll finally get a hobby, or travel. Who knows. The world is a big place.

But for now, Walker has work to do. While we watch these Warriors, he must remain vigilant, watching over them. Watching us.