Eye On The Prize: How Kyrie Irving got LeBron's Cavaliers back to the Finals

Your teams on the go or at home. Personalize SI with our new App. Install on iOS or Android. This story appears in the June 6, 2016, issue of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED. To subscribe, click here.

If this is indeed LeBron James’s moment—when he adds an NBA title with the Cavaliers to his two with the Heat, making Cleveland forget all of its sports misery forever, or at least until the next Browns game—then how would we know?

We could look at James, who has regained the explosiveness of his early years, making him the league’s most athletic cagey veteran. We could examine the cast around him. Power forward Kevin Love finally seems comfortable as a Cav, and point guard Kyrie Irving is putting up postseason numbers that would make Golden State’s Splash Brothers proud: 24.3 points per game, 48% shooting from the field, 45.6% from three.

Or we could look in the stands for general manager David Griffin. A year ago we might not have found him. The Cavaliers filled Griffin with the angst of a thousand teenagers, and he couldn’t take it. He would leave his seat behind the basket at Quicken Loans Arena and dart into his office next to the locker room. Or, on the road, Griffin would go from his spot behind the visitors’ bench to the empty locker room and watch on TV.

It wasn’t the losing that got him. The 2014–15 Cavs did not lose much—they went 53–29 and made it to the Finals—and anyway, Griffin believes there is value in losing. “It would drive me crazy to watch us not buy into each other,” Griffin says. “You can fail at moments in our league and improve. I didn’t want to see us give away opportunities to get better. That was far more troublesome to me than just not winning the game.”

• Open Floor Podcast: NBA Finals preview, goodbye to the Thunder and more

His disappearances were so predictable that one of his front-office colleagues, Raja Bell, would see the Cavs disintegrating on the court and tease his boss: Time to get up, Griff. A few times during last year’s playoffs Griffin ended up watching the action on TV with Irving, whose postseason ended in Game 1 of the Finals. With the point guard out with an injured left knee, Cleveland’s opportunity to win the 2015 championship vanished. But its chance to win the 2016 championship started to bloom.

Last June the Cavs almost became the first Finals team to hold open tryouts. Irving was out. Love was out with a separated left shoulder, suffered in a first-round win over the Celtics. LeBron was all in, but with reserves such as point guard Matthew Dellavedova forced to play starring roles, Cleveland was not going to beat the Warriors.

LeBron James is King of the East, but can he carry Cavaliers to title?

Griffin says James “probably knew we weren’t good enough, but he thought we were going to overcome it because we were so committed.” That commitment had come and gone all season, like a cellphone signal in a parking garage. And yet, in the Finals, Irving saw the undermanned Cavs chase every rebound and power through every screen—and a far more talented Golden State team match that intensity and win in six games.

“Kyrie began to gain an appreciation for how difficult it is to be good,” says the 46-year-old Griffin. “His time away from actually playing helped him understand the things he needed to do better. It made him realize the effort it takes.”

Cleveland is heading back to the Finals—healthy, fully loaded and focused. Griffin stays in his seat now. The Cavaliers might not win, but at least they understand.

In his 13th season, James is such an overwhelming force, both as a player and a topic of conversation, that we tend to view everything Cleveland does as a referendum on him. Is he happy? Is he relying on his teammates too much? Or not enough? Is he undermining his coach? Why did he un-follow the Cavs on Twitter? Why wasn’t his inbounds pass more energetic? Michael Jordan never threw an inbounds pass like that!

But the 31-year-old James is also the league’s most proven player. Irving is only 24, and while he is in his fifth season as a pro, he is in just his second at LeBron University.

Two summers ago Irving; his father, Drederick; and his agent Jeff Wechsler met with the Cavs in a private room at an Italian restaurant in New York City to discuss a maximum-salary contract extension. Irving was an irresistible talent but an incomplete player: He would score 30 points, give up 25, and see his team lose. That is what young NBA stars do.

At dinner, the name “LeBron James” was never mentioned. (“Not one time,” Griffin says.) The Cavaliers were planning on making a free-agency run at James but didn’t think they would land him. They had missed the playoffs for four straight seasons. Griffin privately believed the best-case scenario was that James would sign a two-year extension in Miami, with an opt-out after one year, giving the Cavs a season to improve as an enticement for James to come home.

When James chose Cleveland, Irving’s role changed. It was as if the Cavs stopped asking Irving simply to put food on the table and started asking him to help cook a gourmet meal. As Griffin says, “For the first time, he really had to learn what it took to be successful. He had never been in a situation where the expectation was excellence every day. Even at Duke, he only played 11 games.”

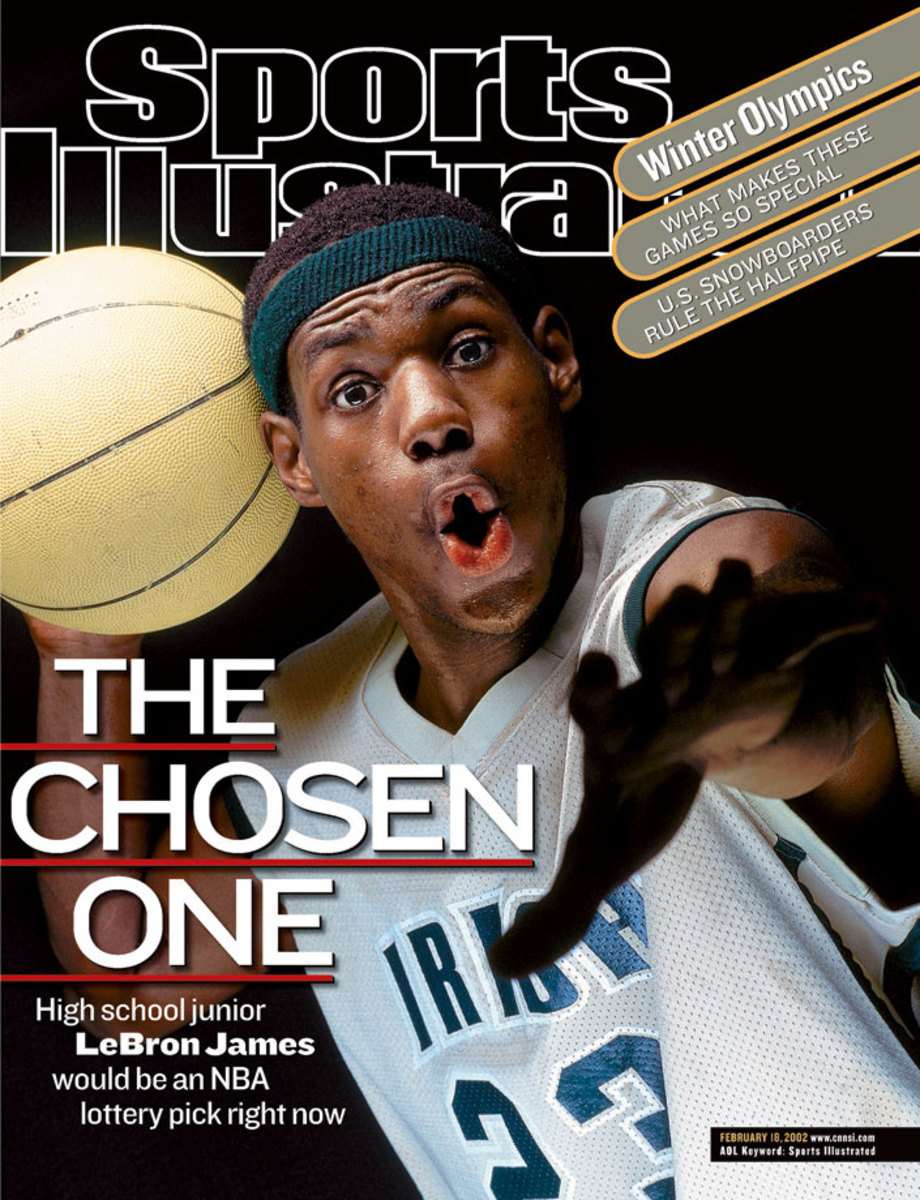

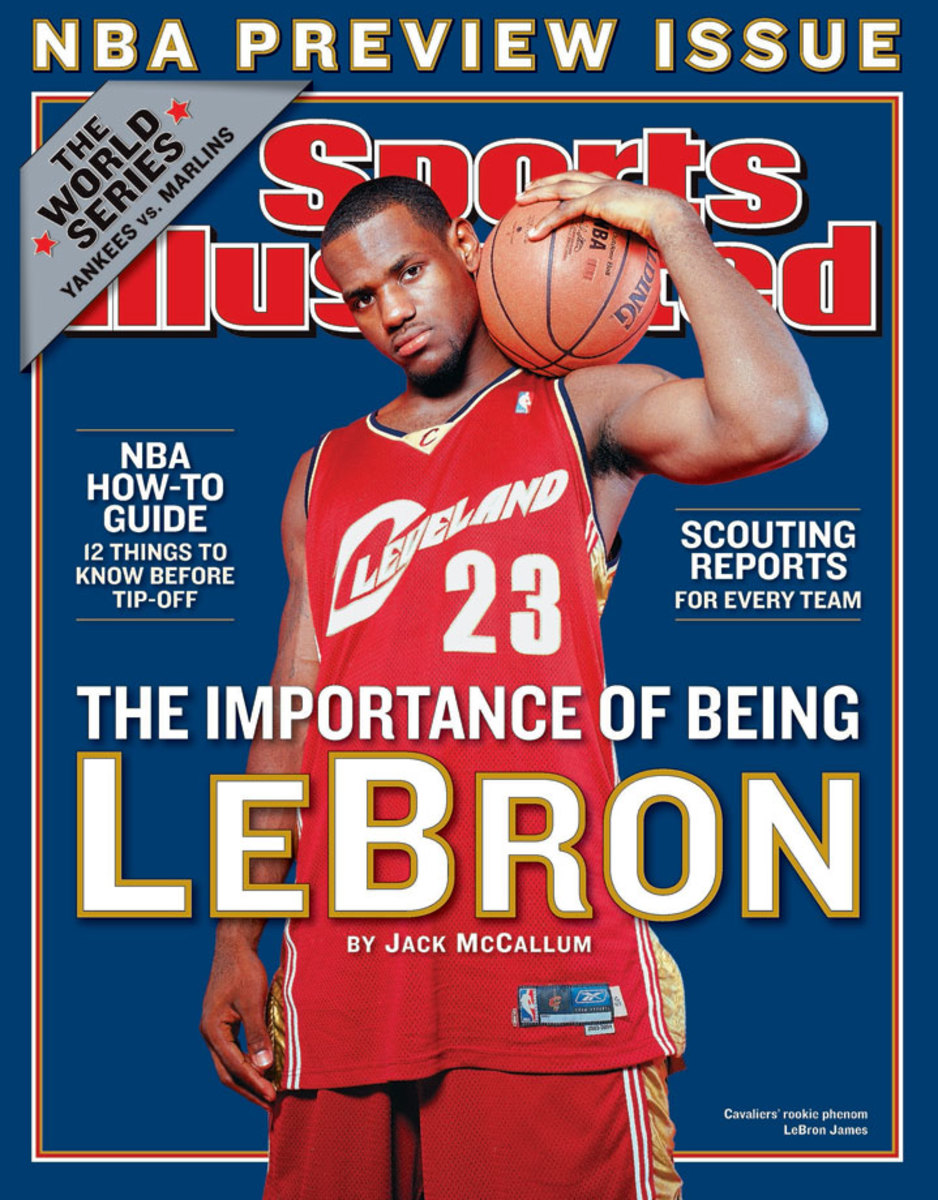

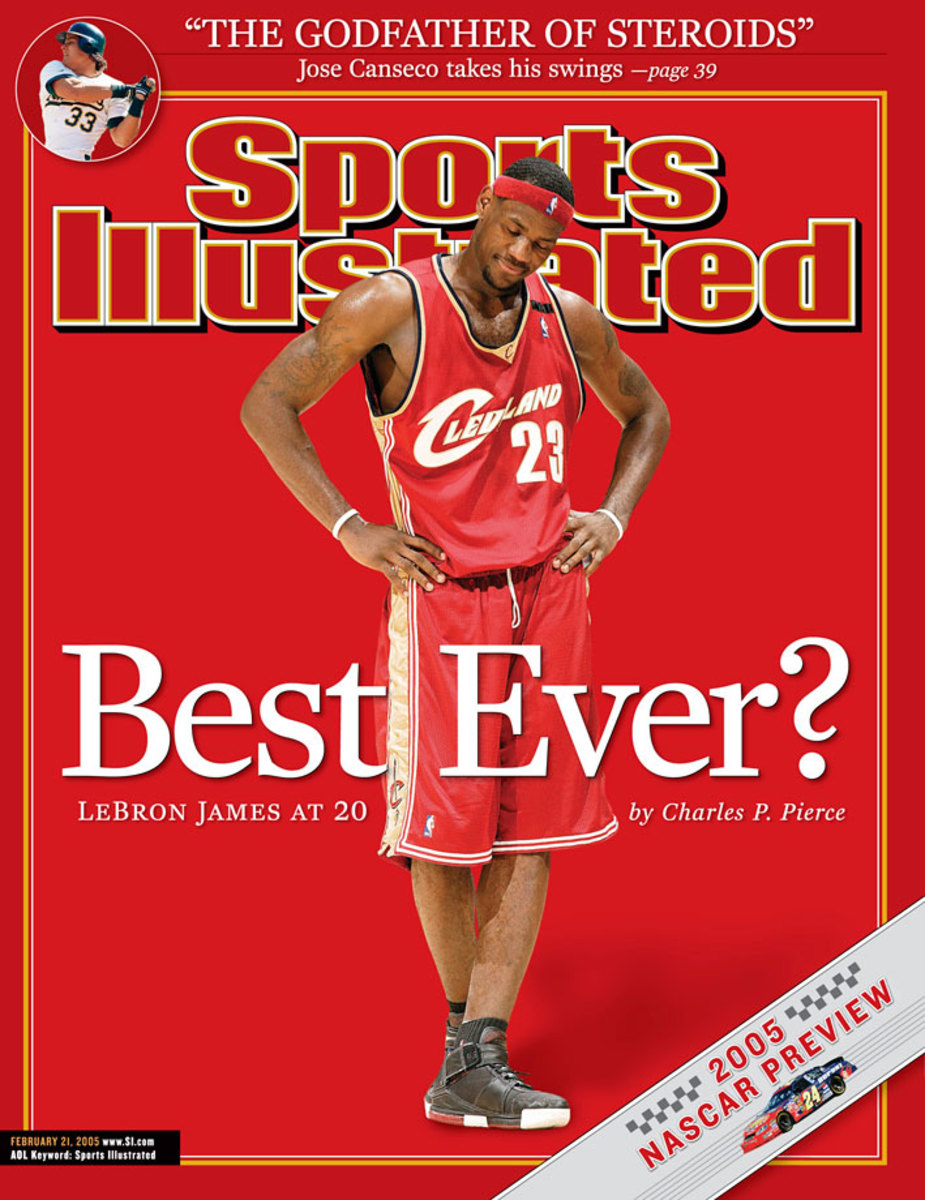

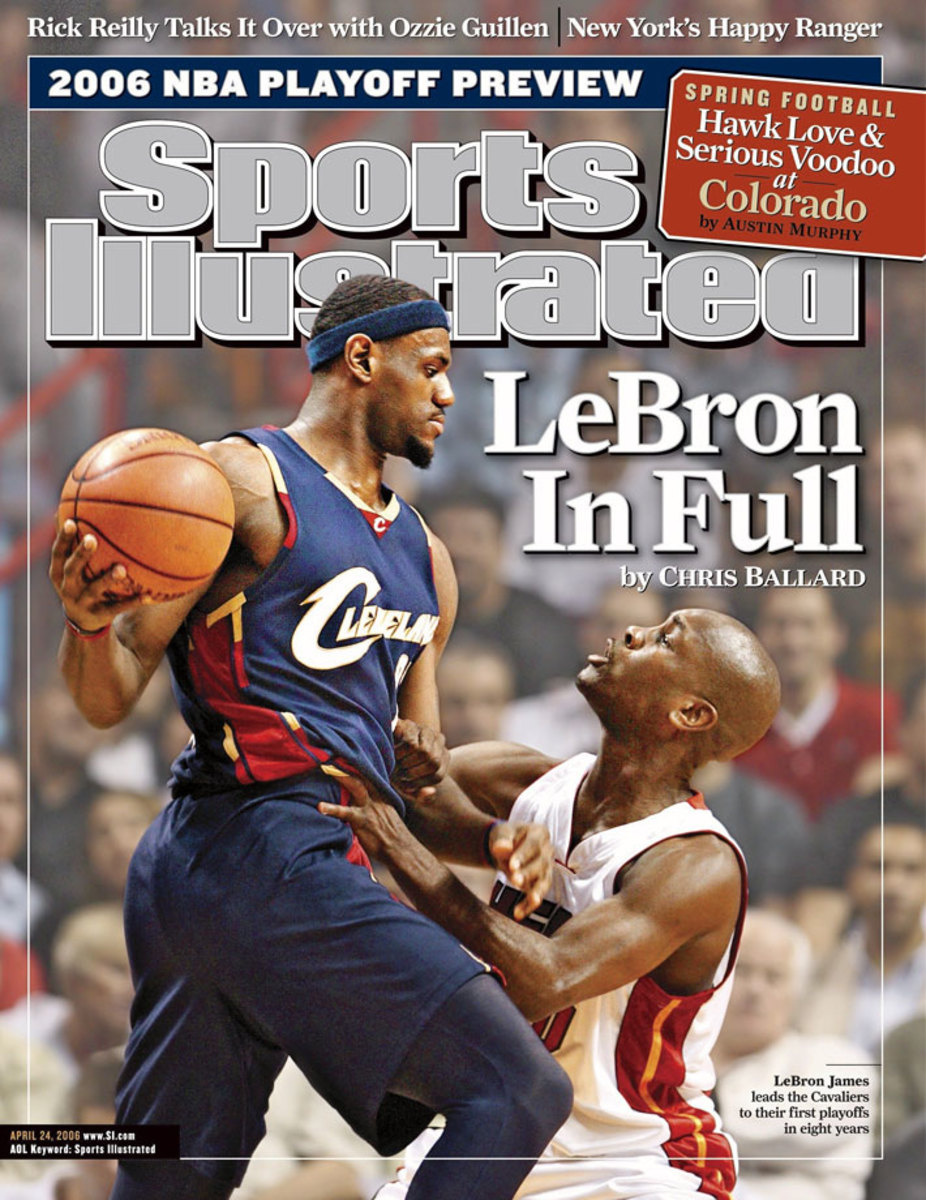

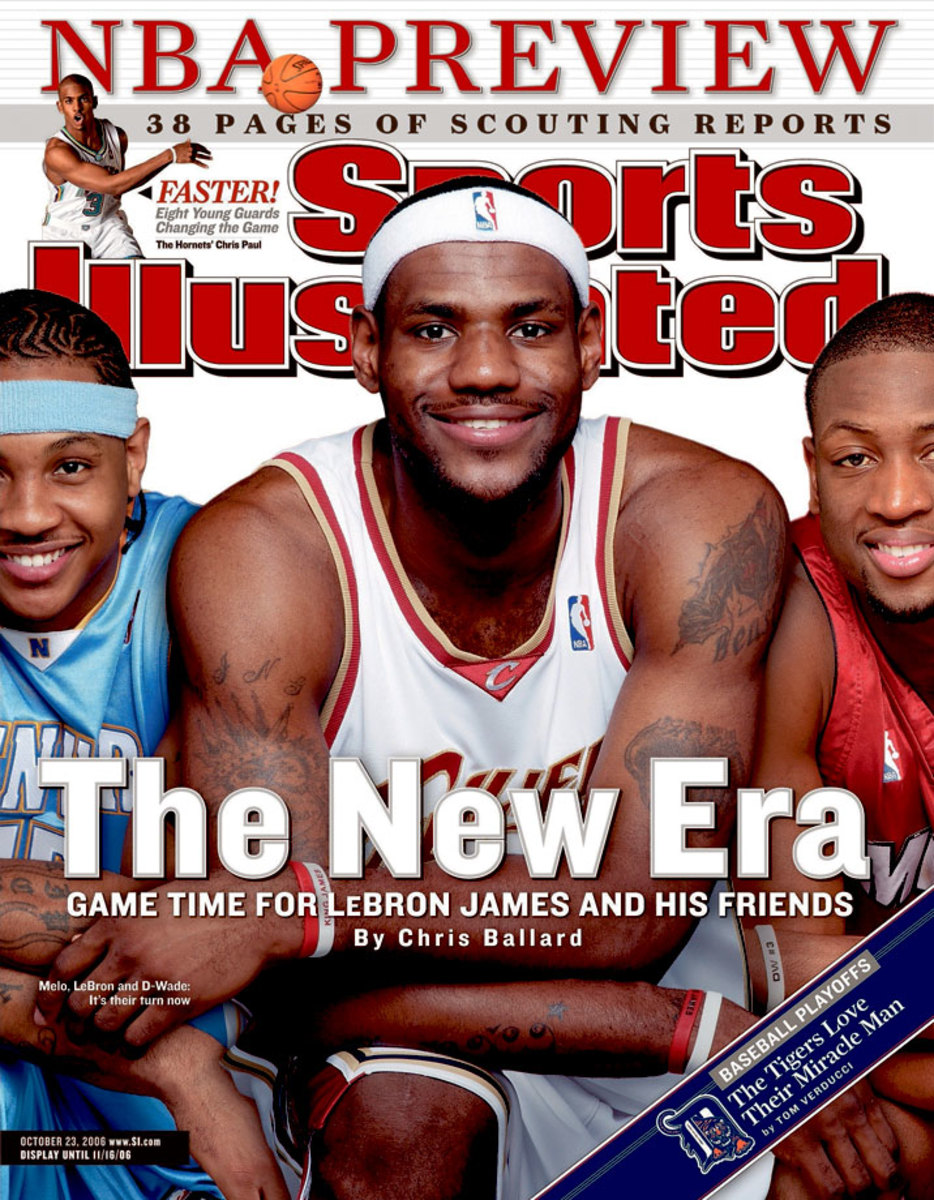

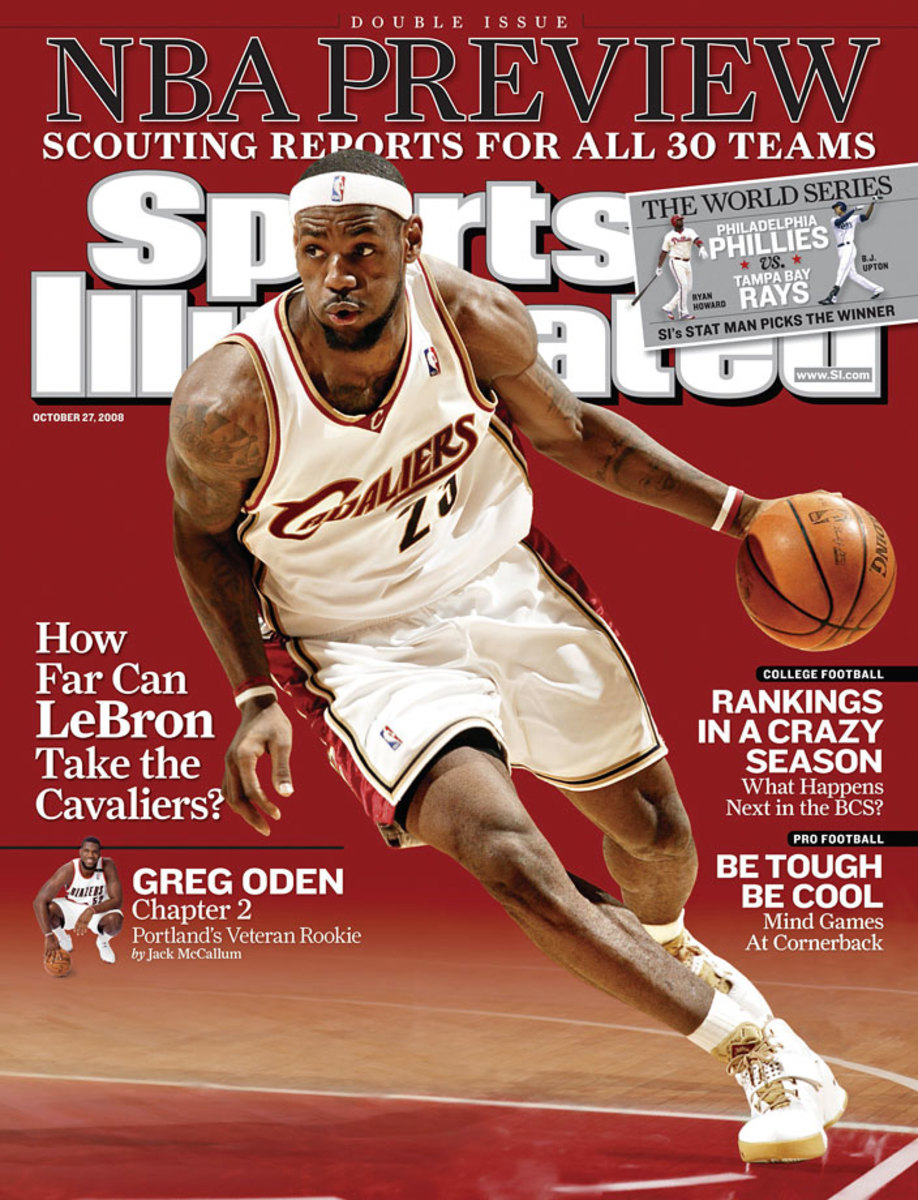

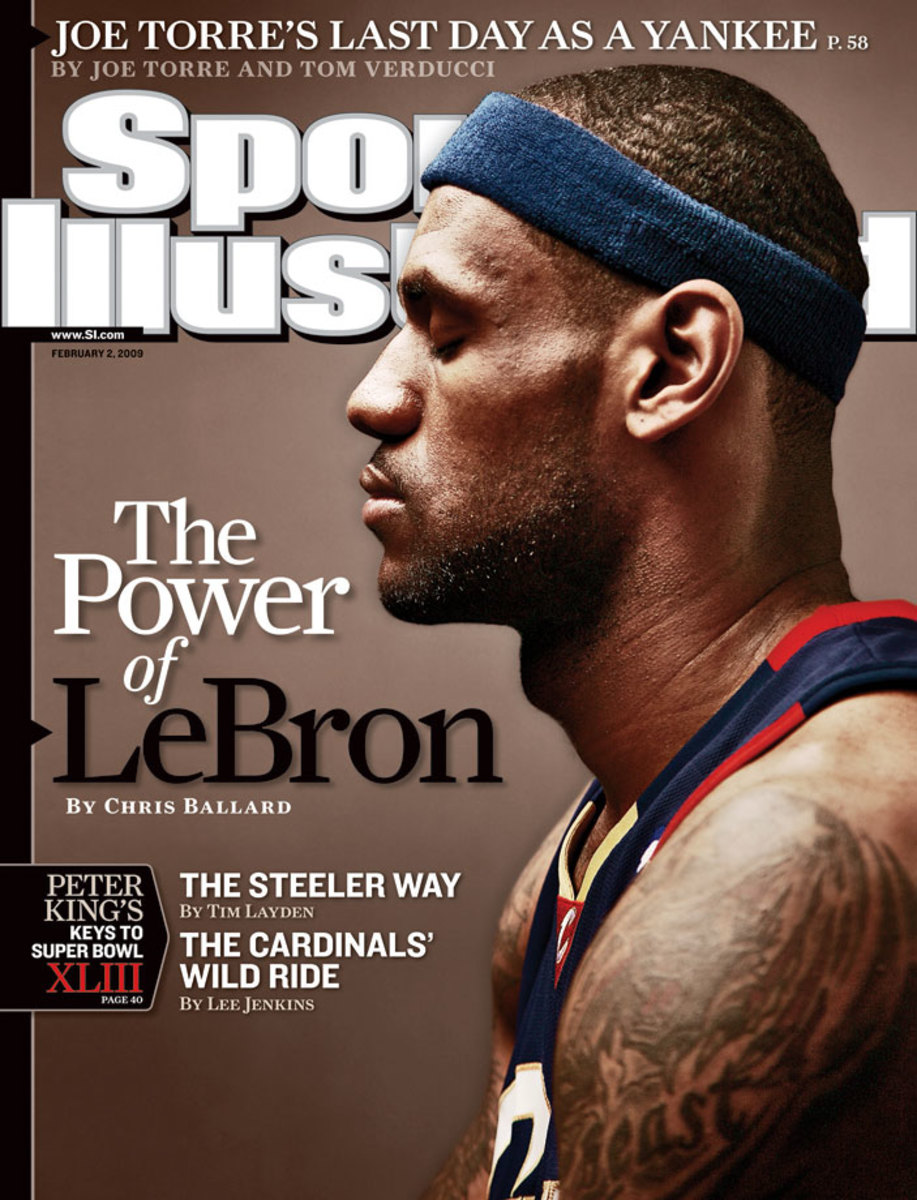

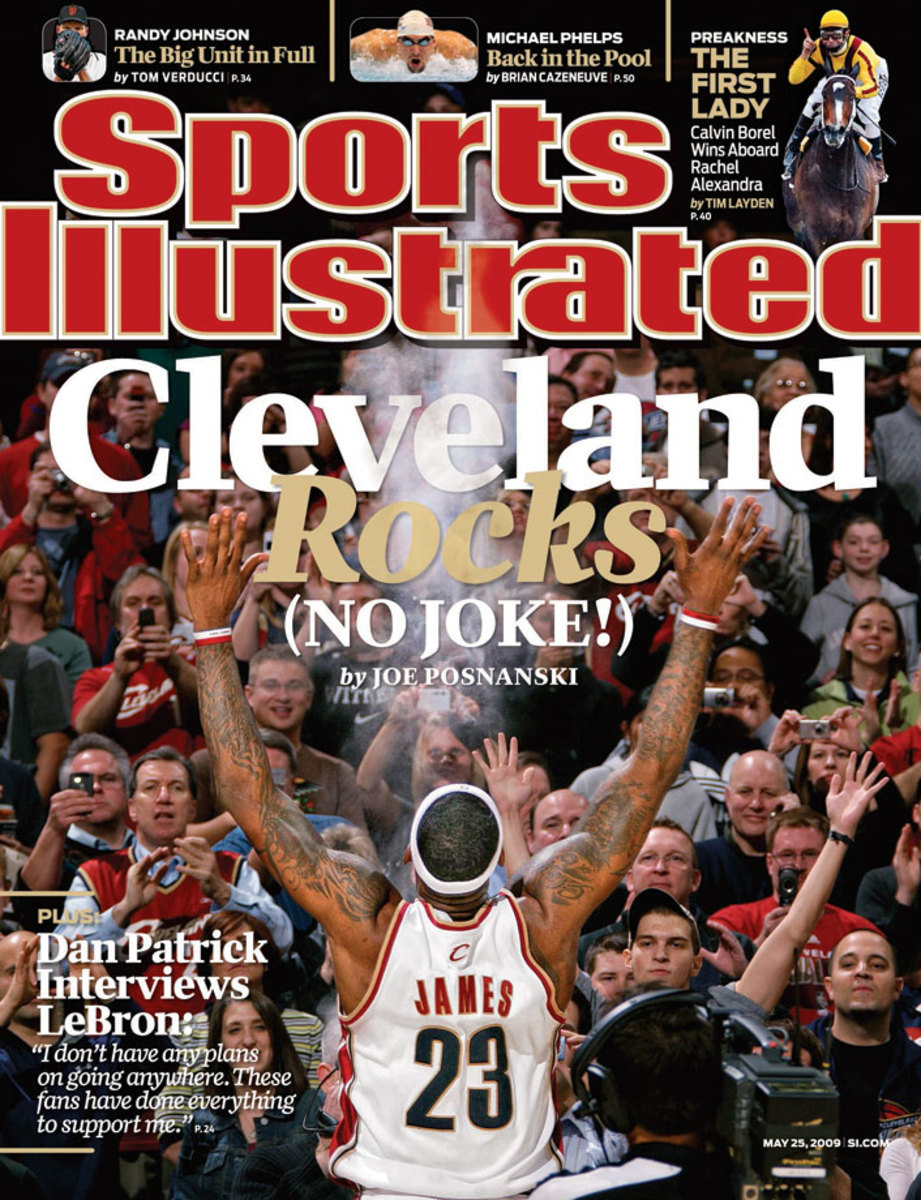

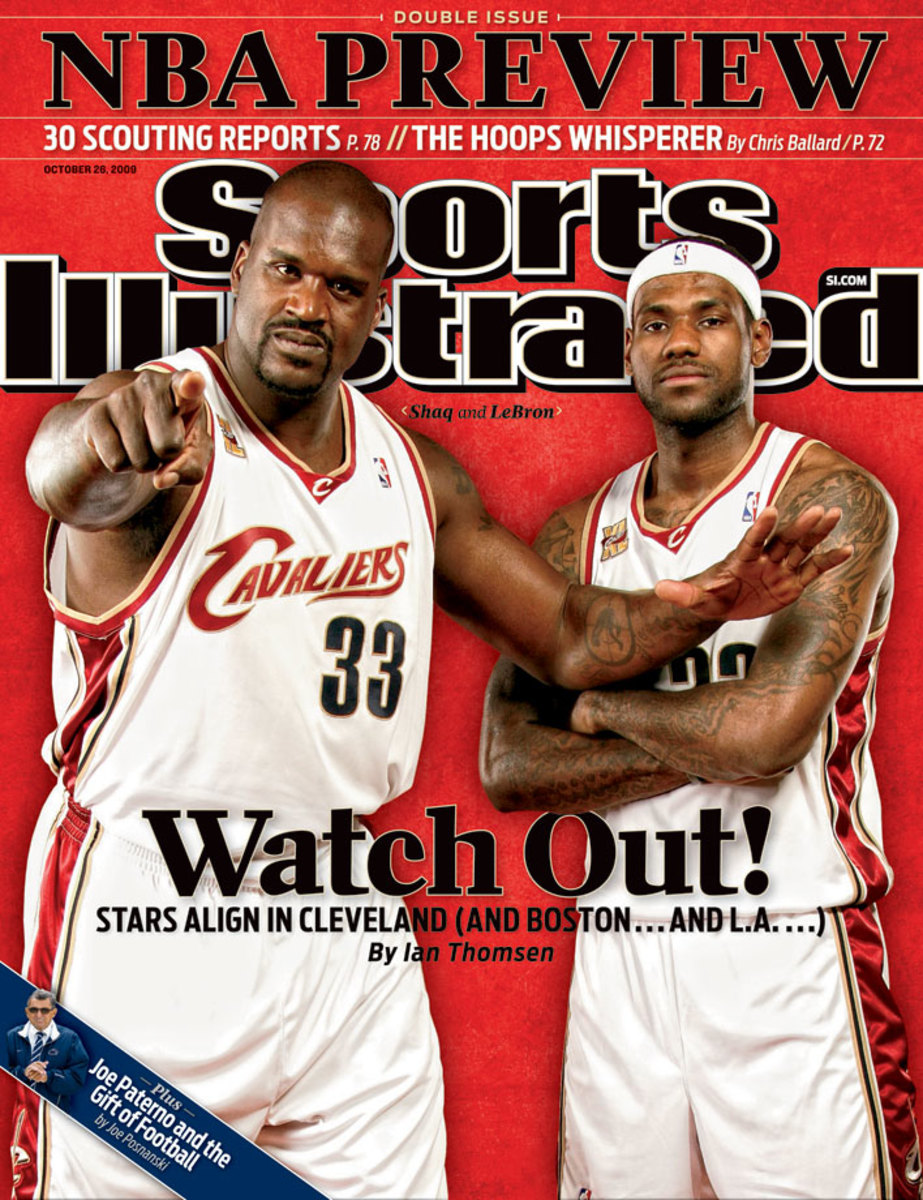

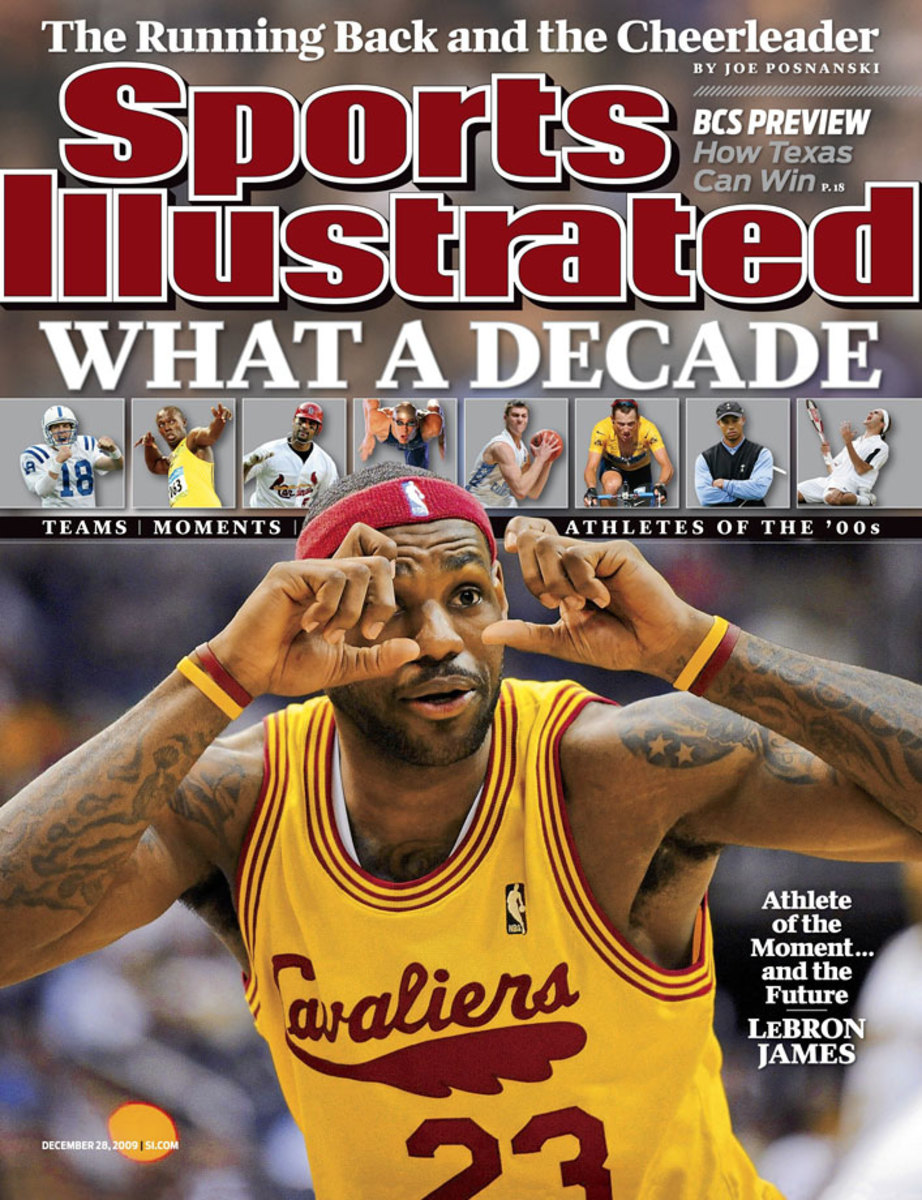

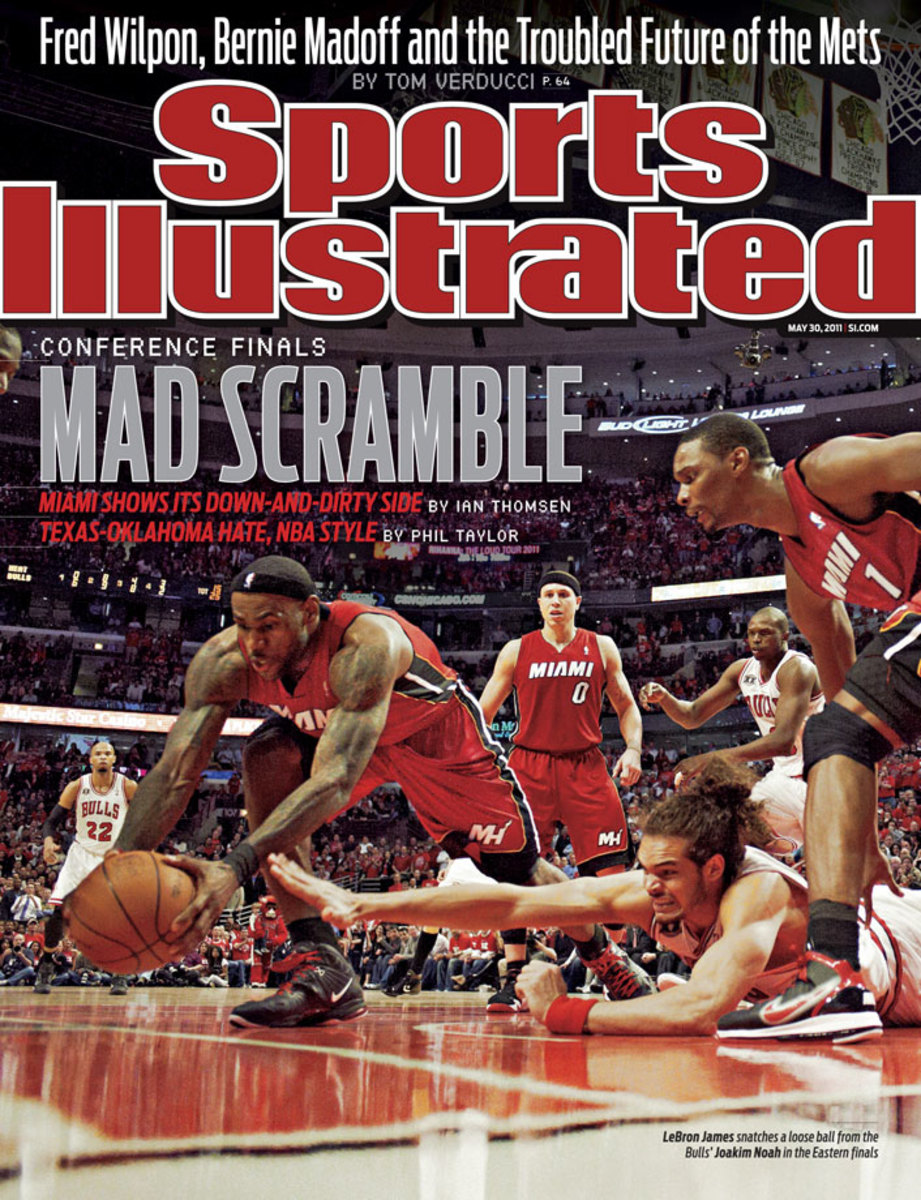

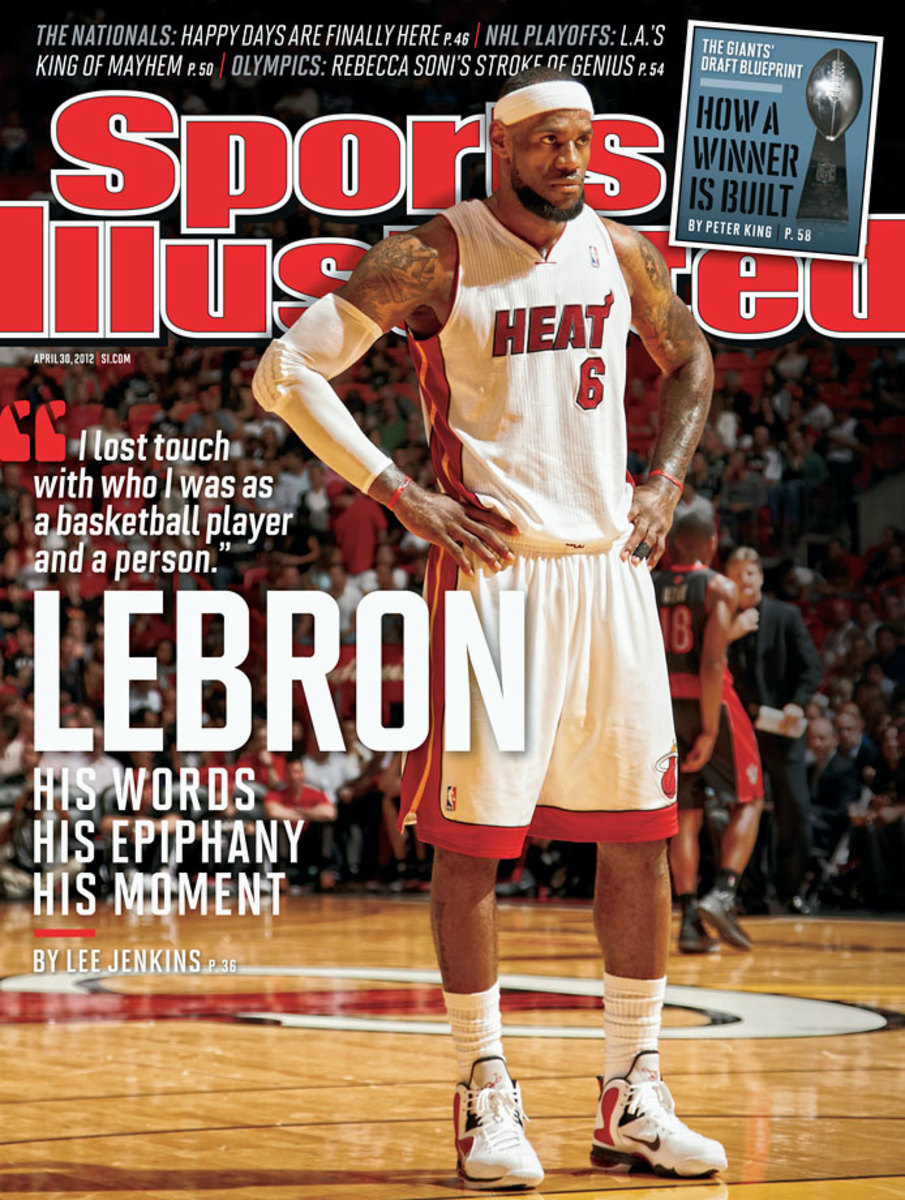

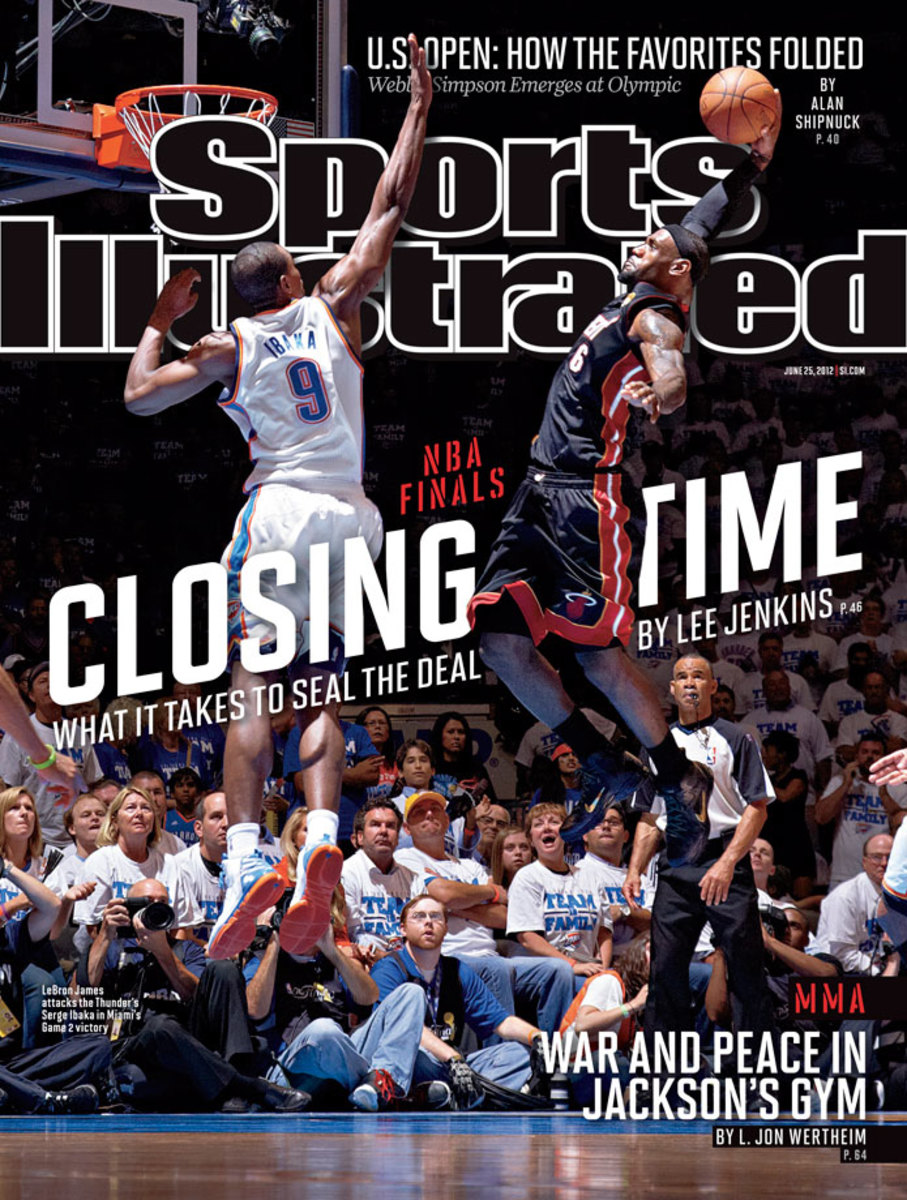

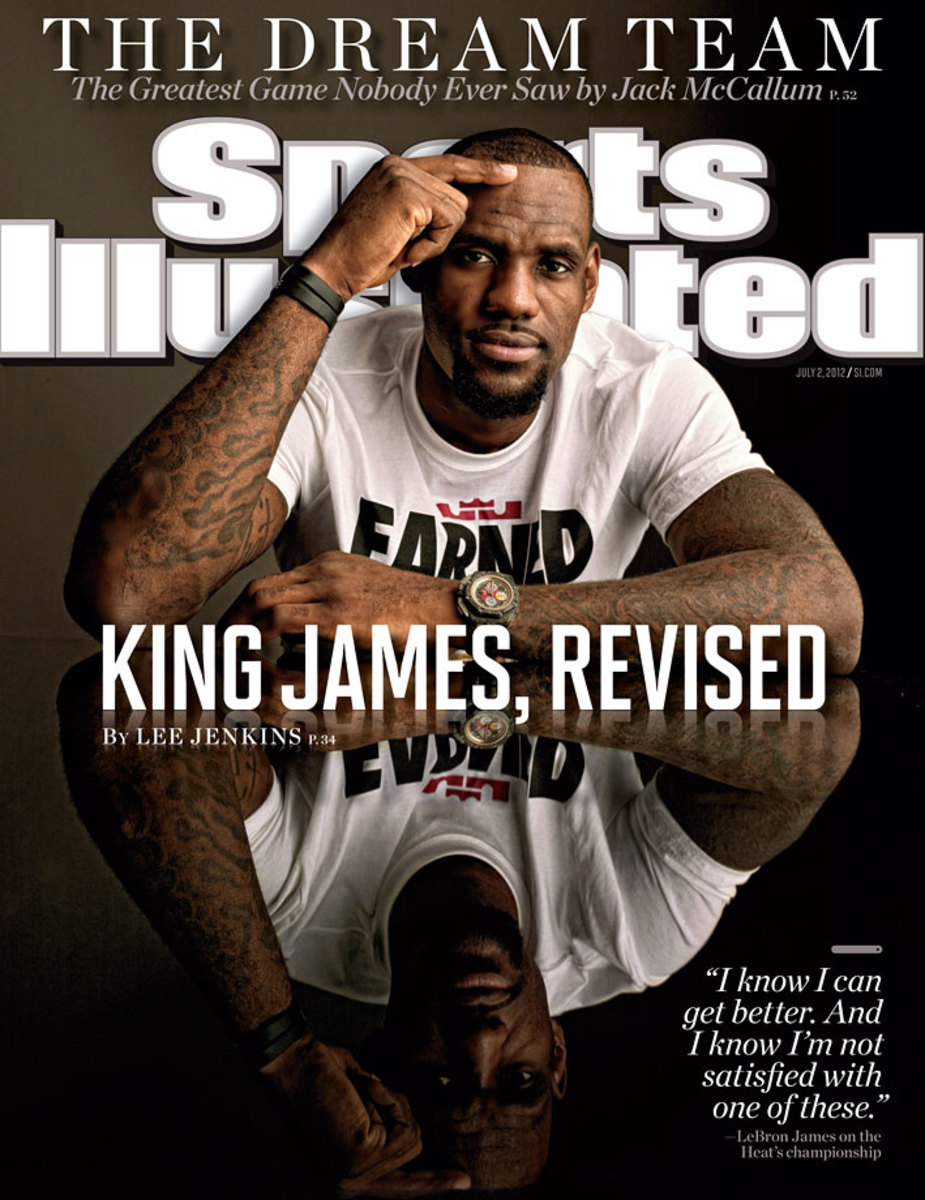

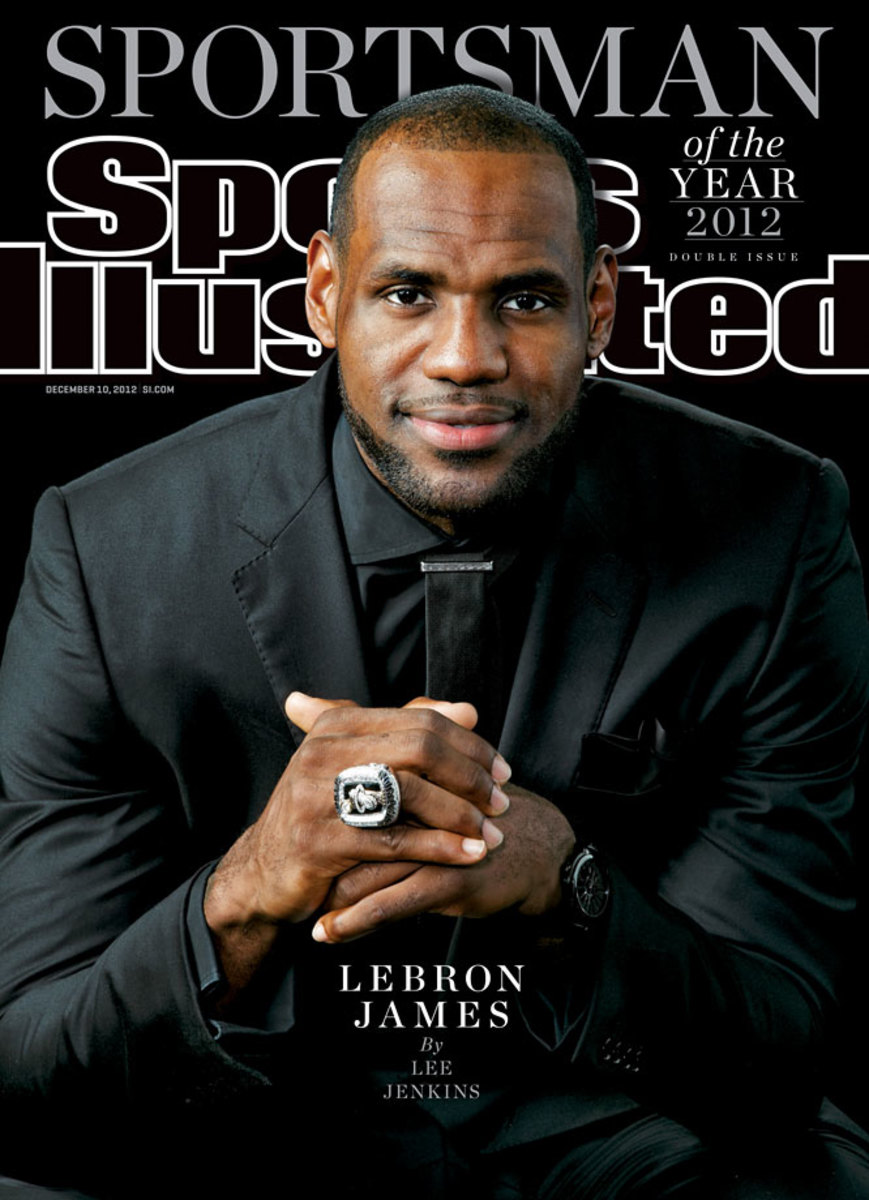

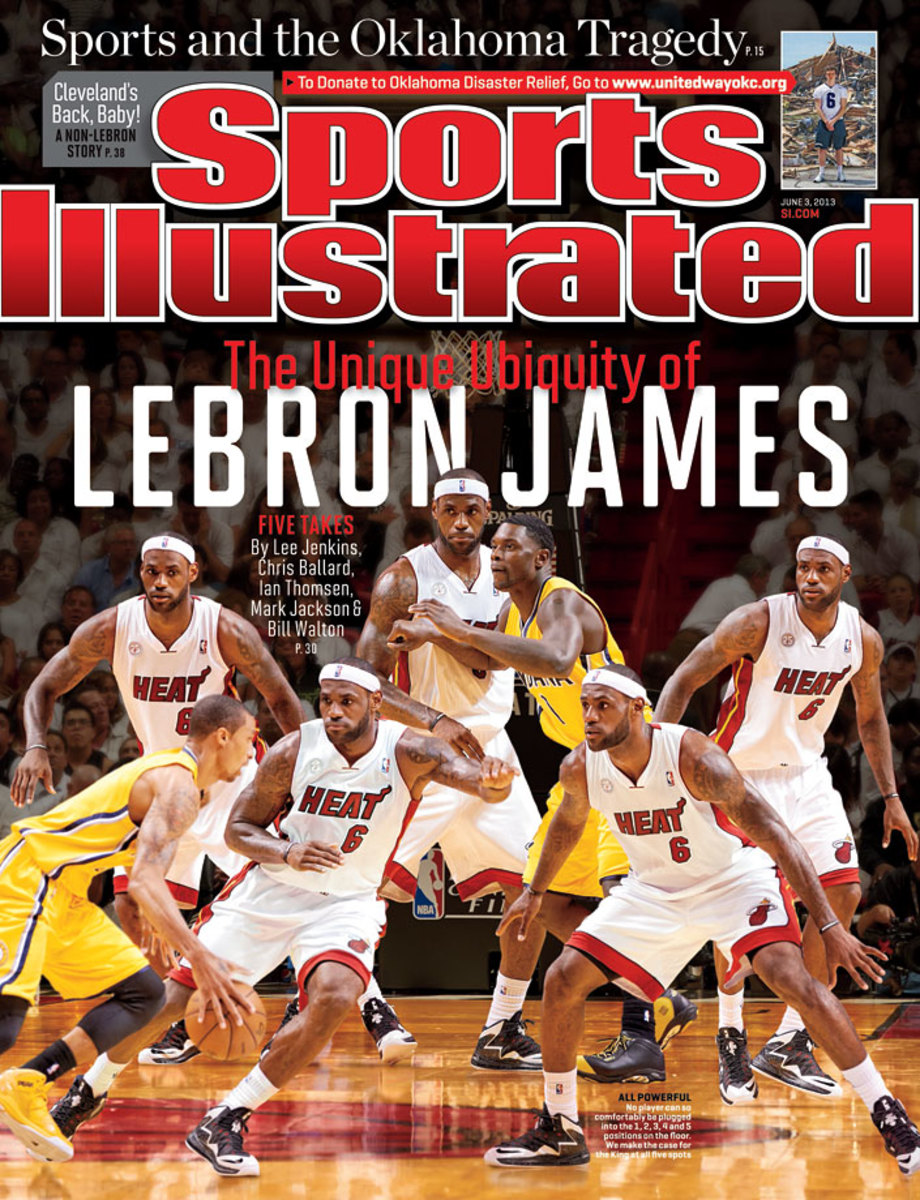

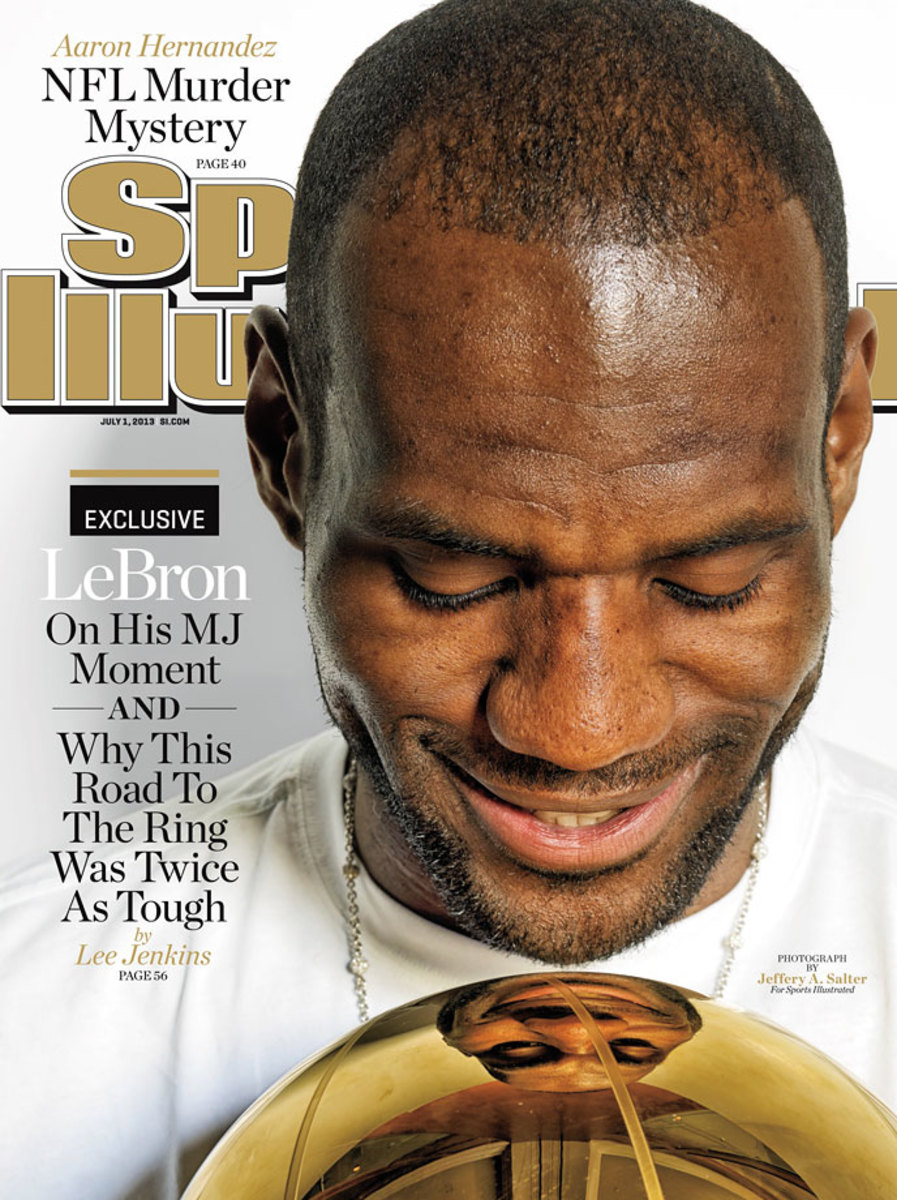

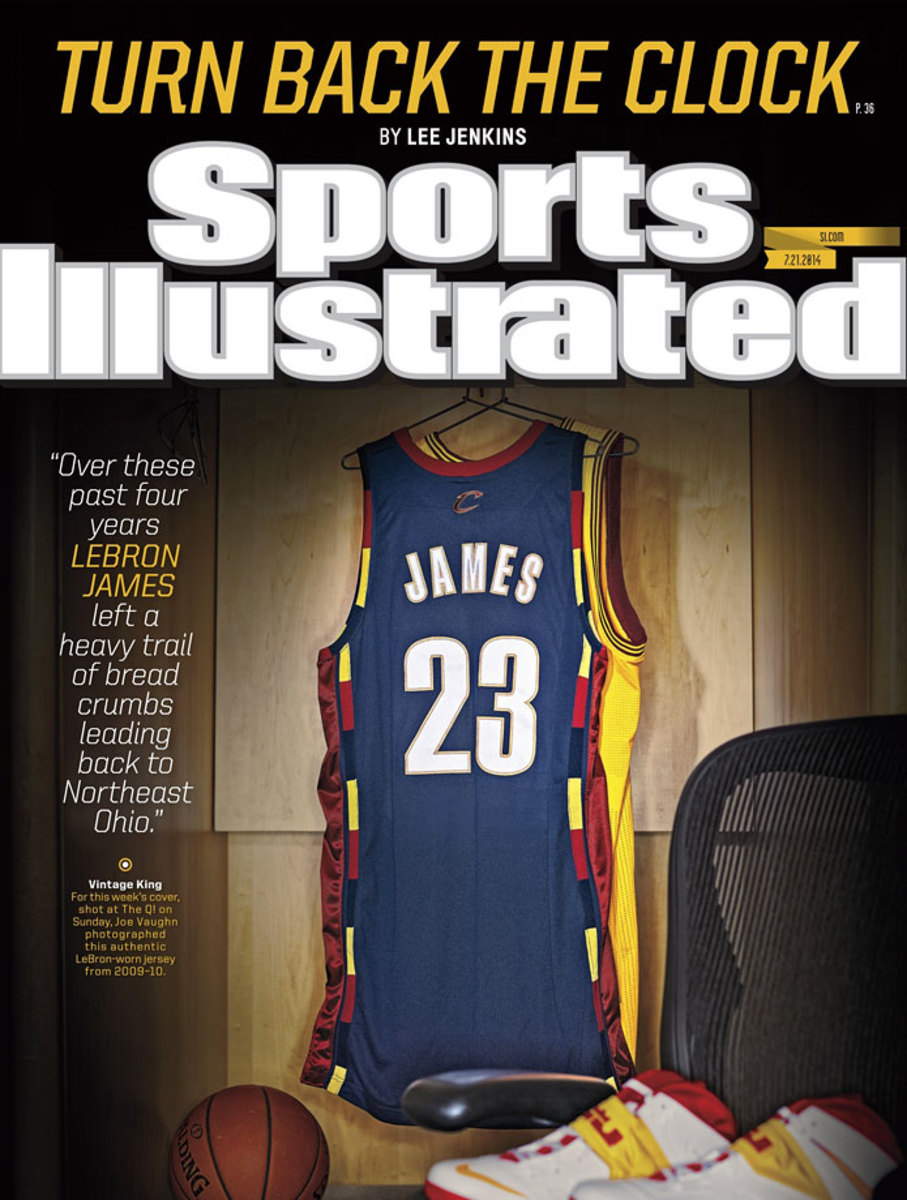

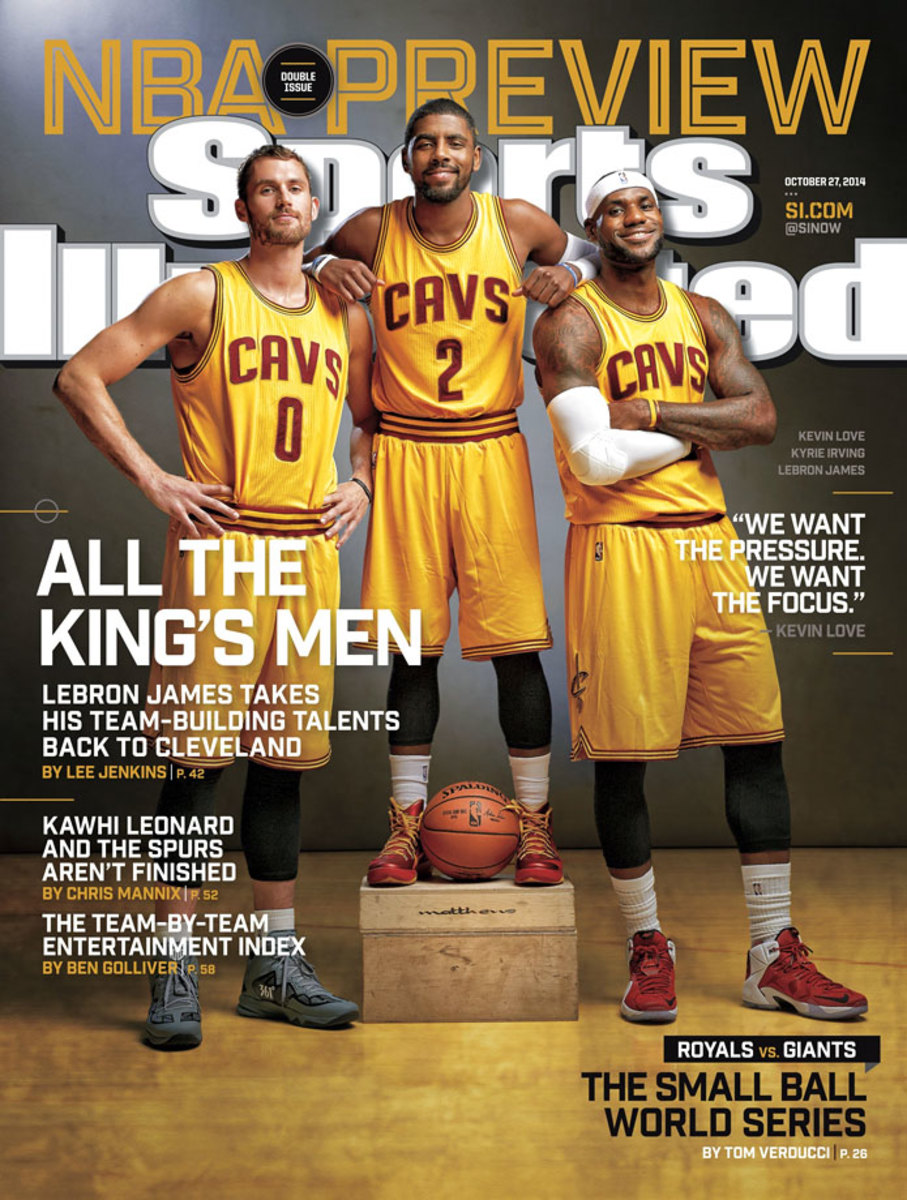

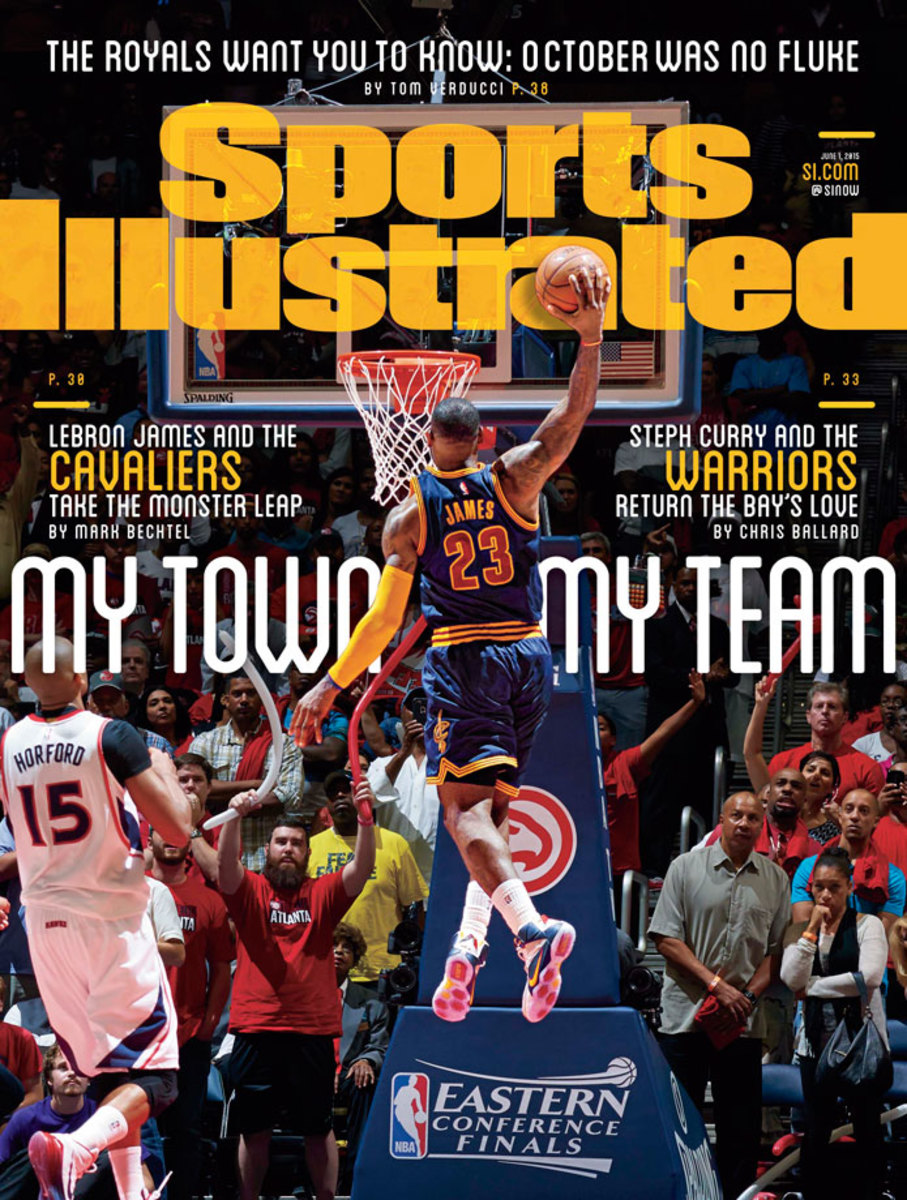

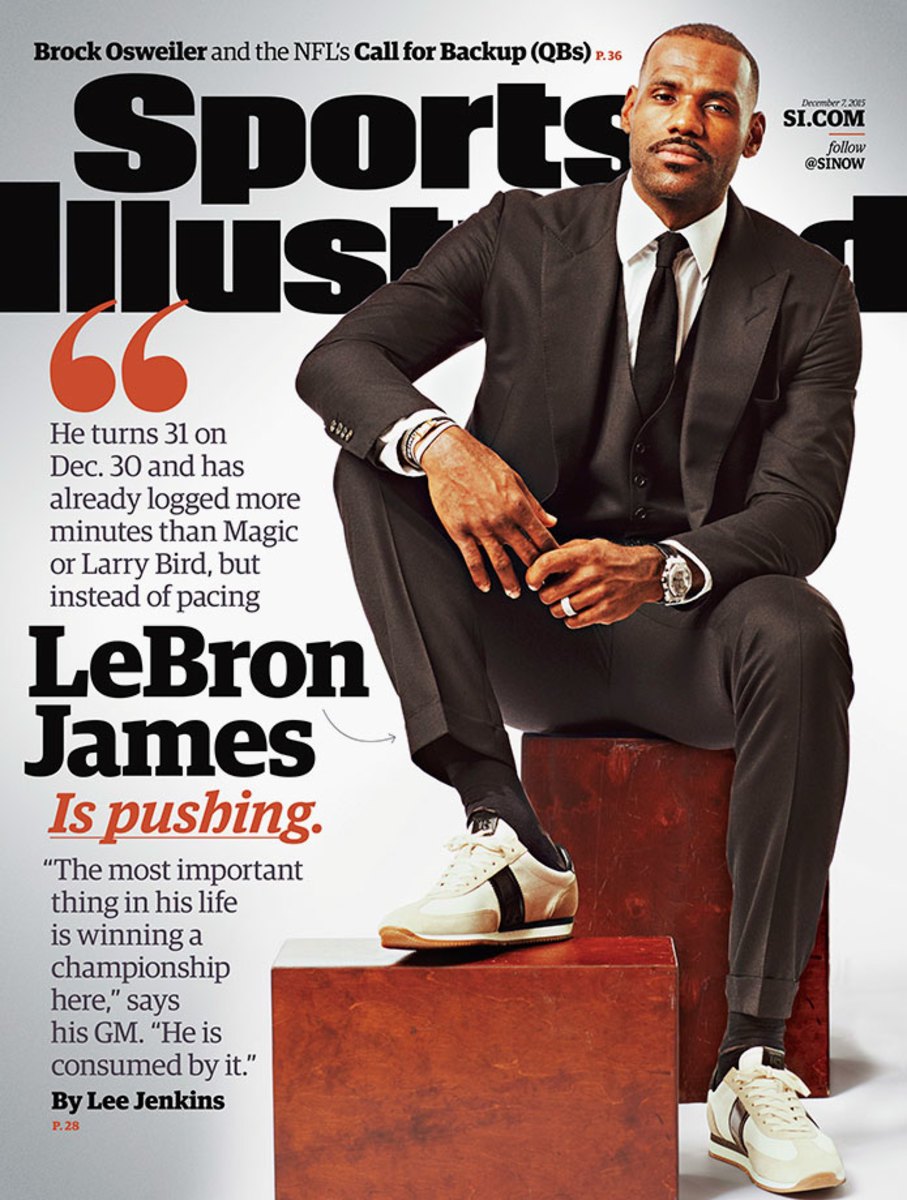

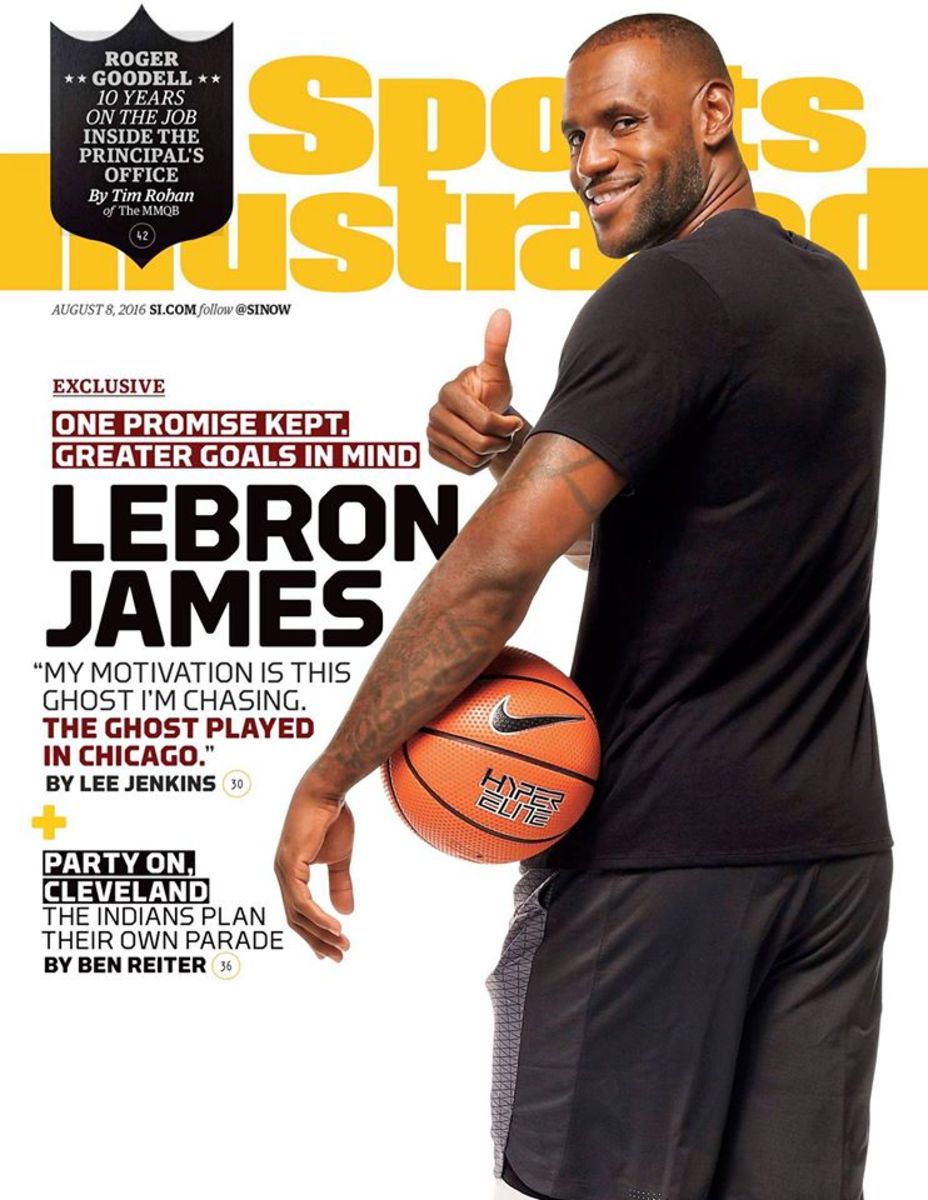

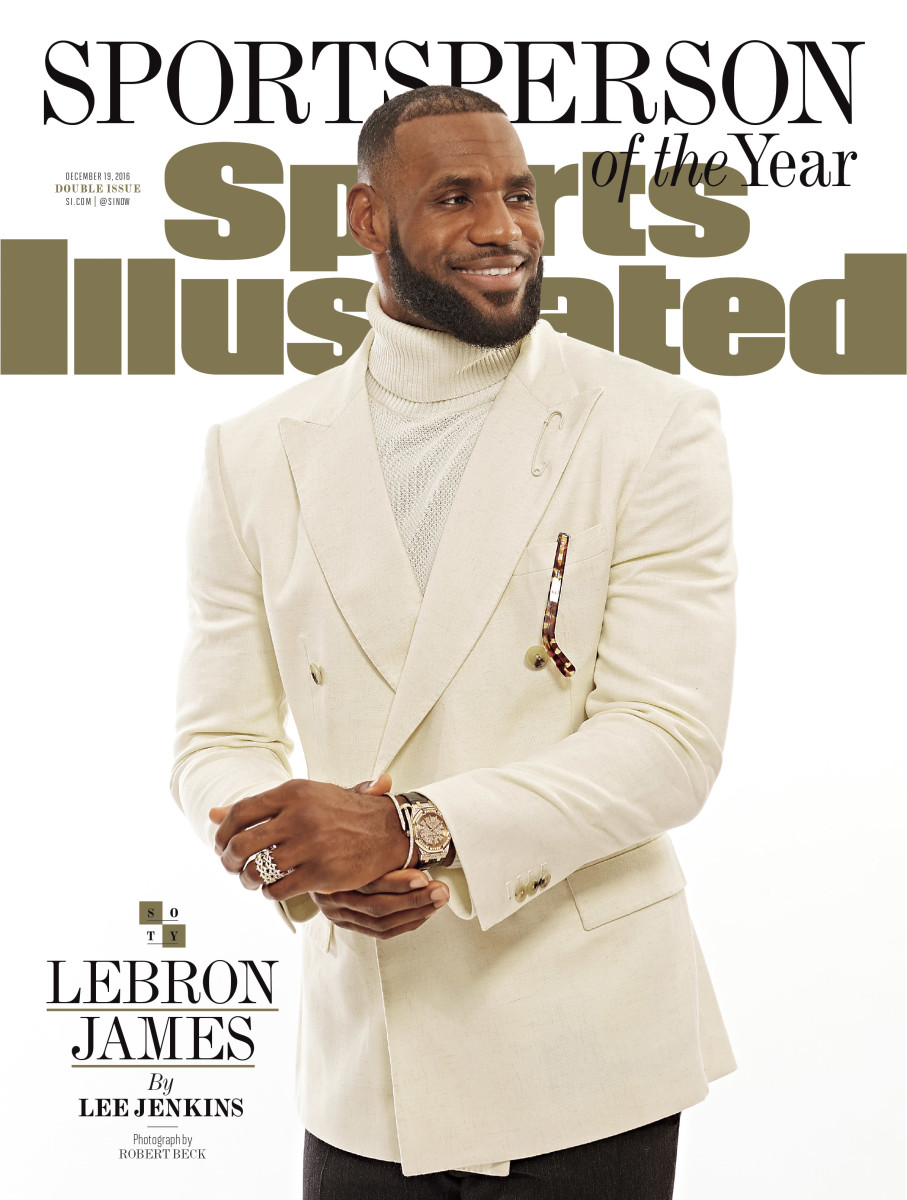

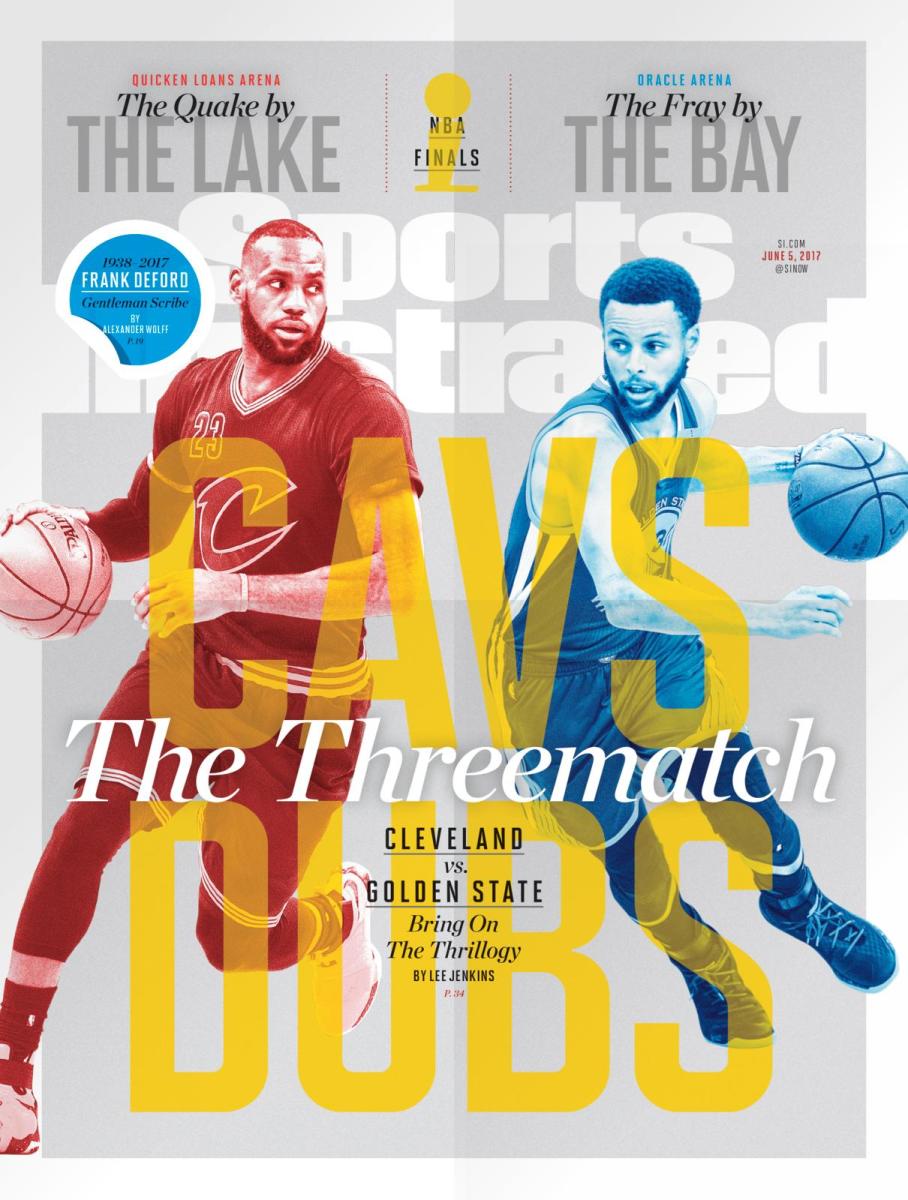

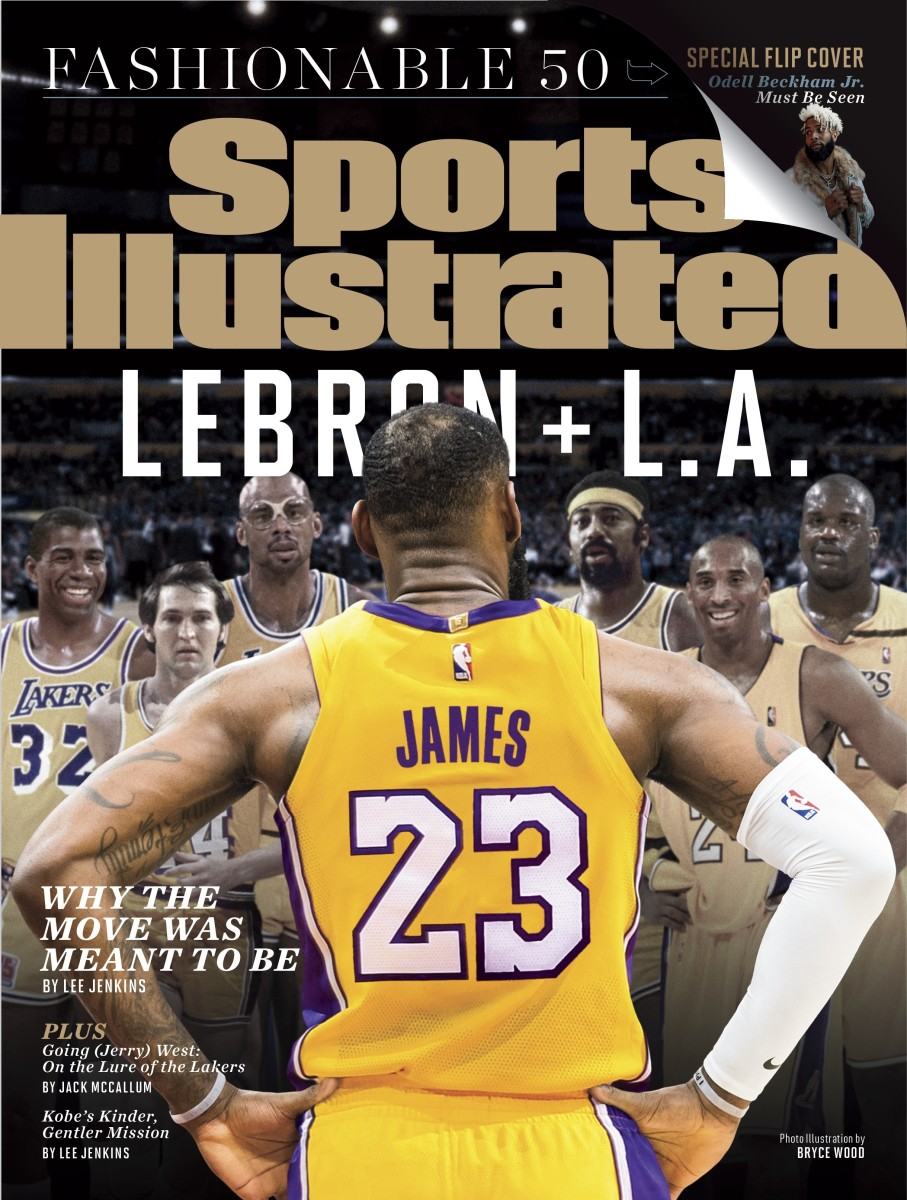

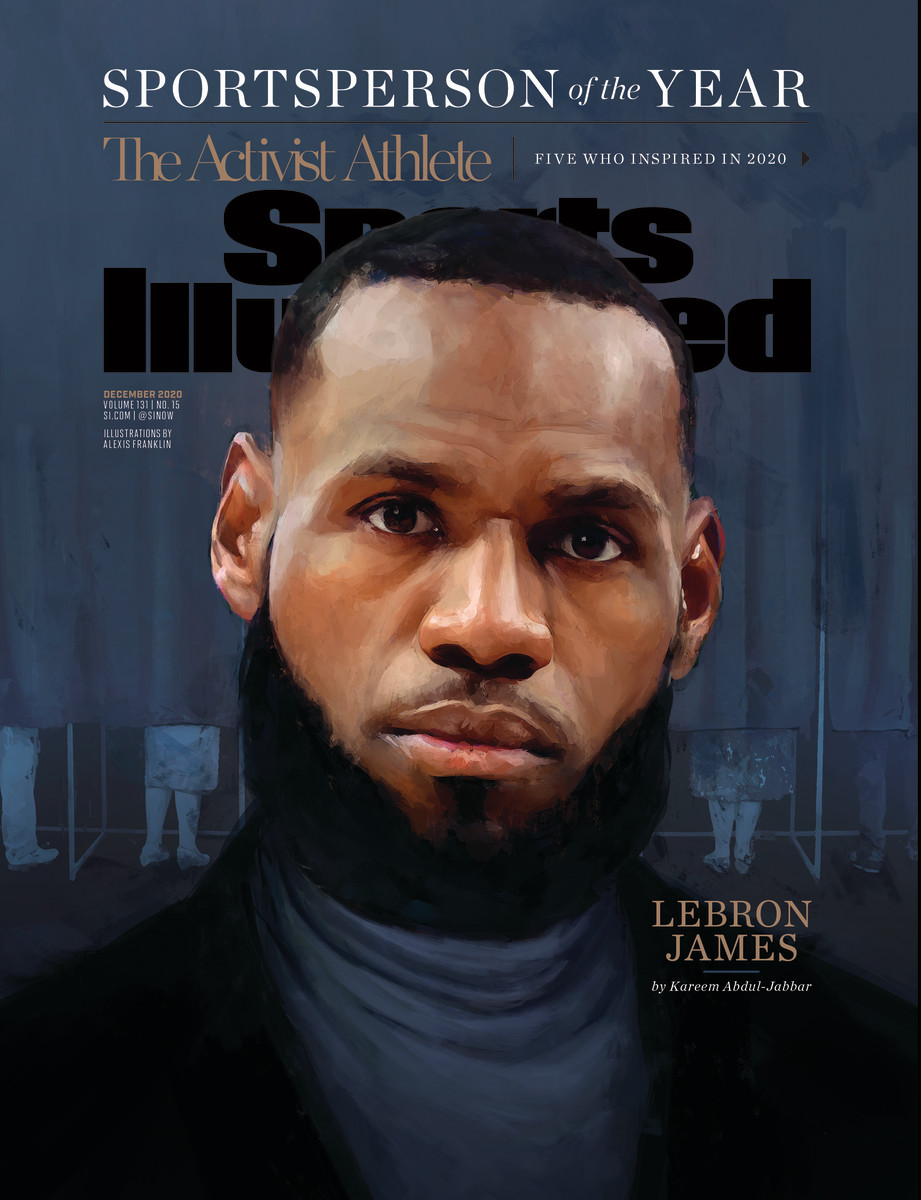

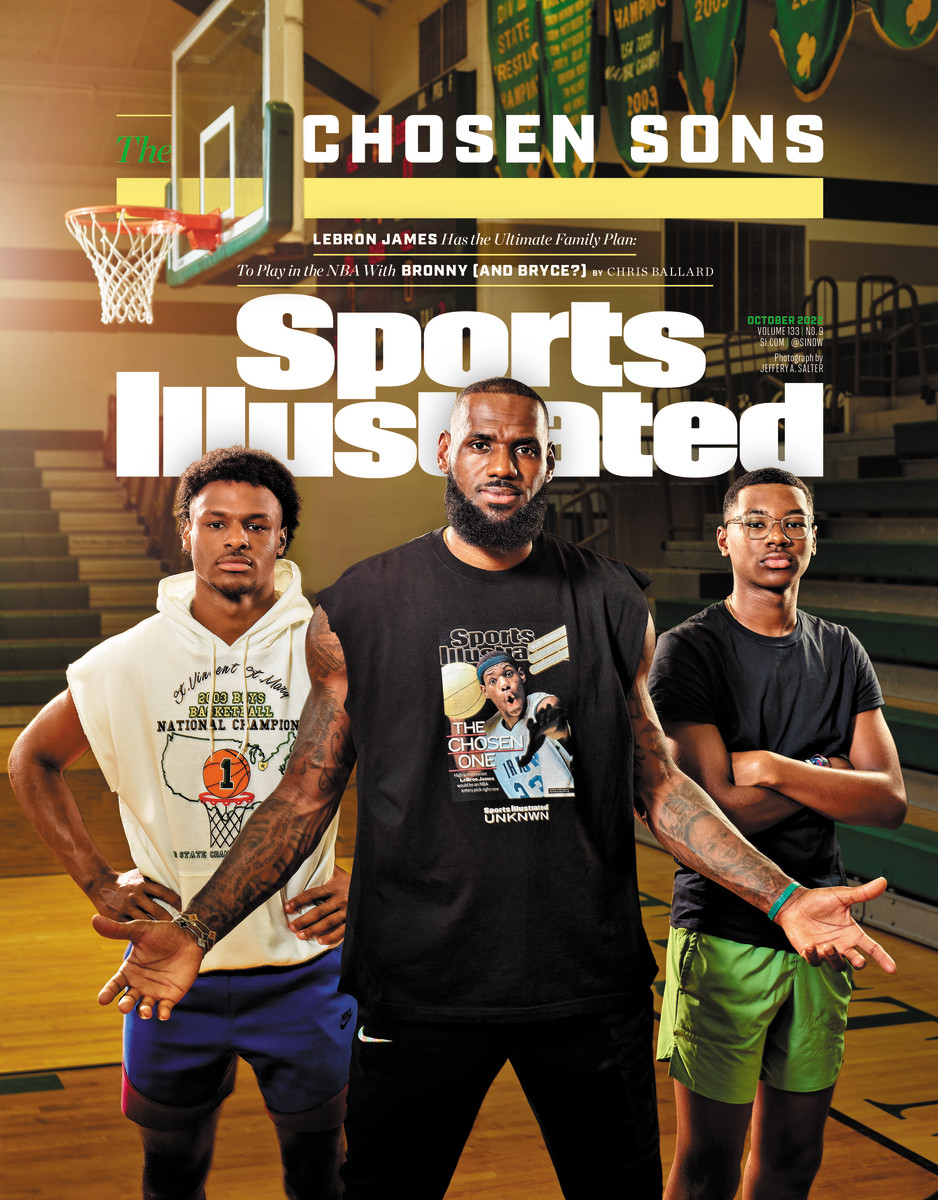

LeBron James’s SI Covers

February 18, 2002

October 27, 2003

February 21, 2005

April 24, 2006

October 23, 2006

June 11, 2007

October 27, 2008

February 2, 2009

May 25, 2009

October 26, 2009

December 28, 2009

July 19, 2010

May 30, 2011

April 30, 2012

June 18, 2012

June 25, 2012

July 2, 2012

December 10, 2012

June 3, 2013

July 1, 2013

July 21, 2014

October 27, 2014

June 1, 2015

June 22, 2015

December 7, 2015

June 27, 2016

August 8, 2016

December 19, 2016

June 5, 2017

October 2, 2017

July 16, 2018

October 22, 2018

December 15, 2020

October 2022

Suddenly, Irving was no longer his team’s biggest star—and a month later, after Griffin traded for Kevin Love, he wasn’t even a clear No. 2. Irving would never be the city’s savior. He would not even lead the team in scoring. “It’s a very big adjustment [from] always being the best player on your team, coming up since he was a kid,” says coach Tyronn Lue, who was an assistant that first year.

James publicly groused about the Cavs’ culture and commitment to winning, and it was easy to interpret those as shots at Irving. James did not have time to ride Irving’s learning curve.

Fans saw James-Irving-Love as the Cleveland version of James–Dwyane Wade–Chris Bosh, but insiders knew better. Forward James Jones, who played with James all four years in Miami and both in Cleveland, says, “Those are two totally different teams, two totally different styles, two totally different makeups, two totally different skill sets. So trying to find similarities with them is really just a futile exercise.”

• MORE NBA: Durant discusses free agency | Kerr's cheat code

When the Heat formed their superteam, Wade had already won a championship in South Beach and Bosh had been to the playoffs twice with the Raptors. Love and Irving had never played in the postseason. Irving had to learn to be a winner and a secondary option in one season. “It just all happened so fast,” Lue says. “I don’t think he had a chance to really sit back and reflect on it until after the season last year.”

Irving is one of the best finishers in the NBA—once he gets past the foul line, rims might as well surrender. But he is not a great offense-starter. When he crosses half-court he does not whip the pieces together quickly, like Chris Paul. He sometimes dribbles slowly in place, as though he is trying to choose from 17 different ways to embarrass the man guarding him.

That gave Cleveland hope after James left, but it was frustrating after James returned. The Cavs wanted Irving to push the tempo, but he was reluctant to do it.

James and Love are such gifted scorers, it was easy to wonder why Irving could not simply become a pass-first point guard. But that’s like looking at the 6' 8", 250-pound James and wondering why he doesn’t play football. At some point, you are who you are; the only adjustments you can make are small. But they are critical.

The Cavs began this season 30–11, but, Griffin says, “we were nowhere near that good.” They had coasted on talent and one of the league’s easiest schedules. The Warriors were chasing history, the Spurs were chasing the Warriors and the Cavs were chasing their tails.

“When things got difficult in a game, we would start to fracture a little bit,” Griffin says. “We would start to try to do everything ourselves. You still see us fall prey to it once in a while—bouts of [isolation] ball, walking the ball up the court: your turn, my turn. We did that an awful lot early on.”

Griffin fired coach David Blatt on Jan. 22 even though Cleveland had the East’s best record. Predictably, people focused on the canning of a successful coach and wondered whether James had orchestrated it. They should have focused on Lue, who has brought the team together, and on Irving, who benefited the most from the change.

Lue understood Irving’s challenge. Almost two decades ago, as a quick little junior point guard for Nebraska, he scored 21.2 points per game. He left for the NBA, where nobody wanted him to score 21 points per game. He averaged 17.1 field goal attempts in his last season at Nebraska; he would not take 17 shots in any NBA game until late in his sixth season.

To survive in the league, Lue had to become a complementary player. But “I couldn’t come off [a screen] and look for the pass,” he says. Lue had to maintain the skills that got him to the league while adapting to the superior talent around him. Irving’s adjustment is not as severe as Lue’s was—he is a far better player—but there are similarities. “Jason Kidd, [Rajon] Rondo, that’s not who Kyrie is,” Lue says. “That’s not going to happen. Kyrie’s passing ability comes off his aggressiveness. If he looks to pass [first], that takes away his aggressiveness, and that’s not who he is. [When] he’s aggressive, looking to score, that opens up his passing, a lot like I was in college.”

The improbable magic of Steph Curry leaves us speechless again

Lue has persuaded Irving to play faster, a necessity in today’s NBA. It was something the organization wanted before, but Irving was reluctant to change the style that had made him an All-Star. The change has opened the floor for everybody.

“Offense for him was so easy in the half-court,” Griffin says. “He would just pull out And1 mixtape moves and do whatever he wanted to do. It took a while for him to realize playing faster and playing with more energy is actually easier for him.” Irving dished out just 4.7 assists per game, but Cleveland had the league’s third-most-efficient offense.

Irving and the Cavs reverted to their old ball-stopping, tunnel-vision mode for Games 3 and 4 of the Eastern Conference finals against the Raptors, the only two times in the playoffs they scored under 100 points—and their only two losses. In Games 5 and 6, Irving scored 53 points and led the Cavs to blowout wins. When James calls him “a young superstar,” it’s not hyperbole or wishful thinking. It’s the truth.

After the Game 5 victory over Toronto, Irving referred to the two defeats as “probably my first two legitimate road games that I’ve experienced in my playoff career.” It wasn’t quite true, but it was close. And it was a reminder of how much ground he has had to traverse in just two years.

The career he signed up for at that Italian restaurant in New York City disappeared two weeks later. He now has a piece of something better. James joins Irving for postgame press conferences, and when they sat down after Game 5, James answered 11 of the 13 questions, including one addressed “to both of you.”

There is no “both of you” in Cleveland. There is James and there is everybody else. Irving will never be Cleveland’s savior. But he may ride shotgun next to the savior at a championship parade.